Table of contents

NRR (net revenue retention)

NRR is the metric that tells you whether your existing customers are quietly compounding your revenue—or quietly eroding it. If you're capital constrained (most founders are), NRR often determines whether growth gets easier over time or whether you must "run faster" every quarter just to stand still.

Net revenue retention (NRR) measures how much recurring revenue you keep and expand from the same customers over a period, excluding new customers. It's the combined result of renewals, upgrades, downgrades, and churn.

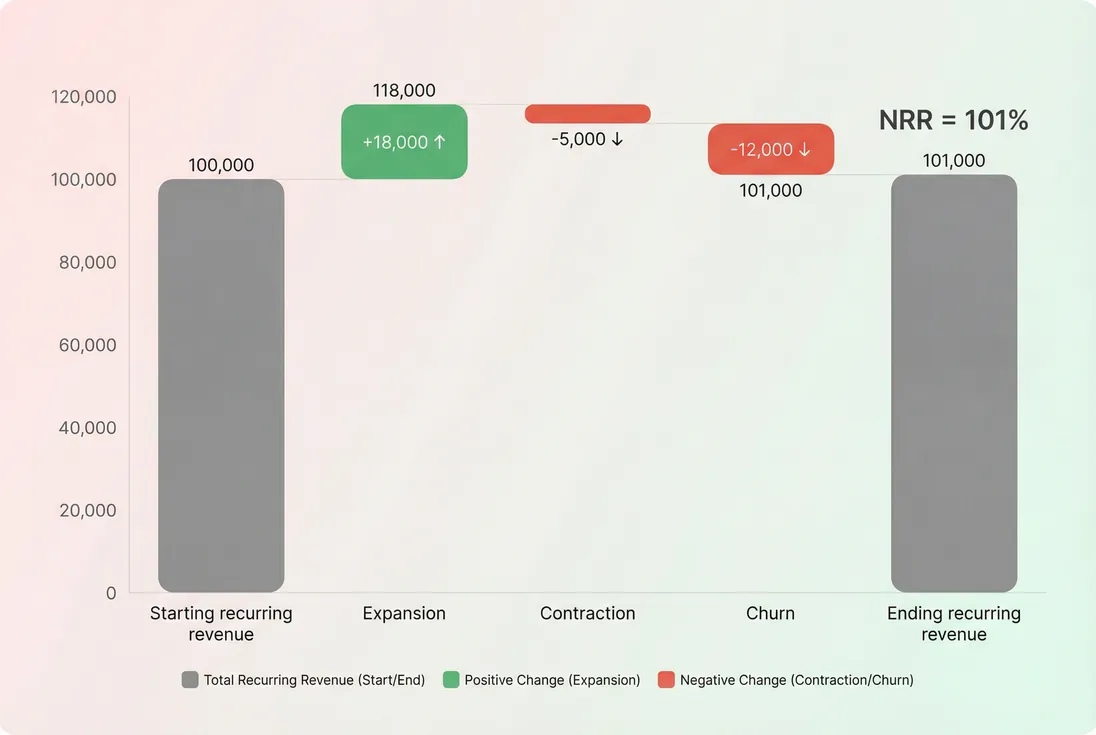

A simple NRR bridge: the same starting customers end the period slightly higher because expansion more than offsets contraction and churn.

What NRR tells you

NRR answers a practical question: If you stopped acquiring new customers, would revenue from your current base grow, hold, or shrink?

- NRR above 100% means expansions (upsells, cross-sells, seat growth, usage growth, price lifts) exceed losses from churn and downgrades. This is also commonly discussed as Net Negative Churn.

- NRR around 100% means you're "treading water" on the base: what you lose you replace via expansion.

- NRR below 100% means the base is shrinking, so new acquisition must cover the gap before you grow at all.

NRR is especially valuable because it compresses multiple realities into one number:

- product value (are customers getting more value over time?)

- pricing power (can you capture that value?)

- retention health (do customers stay?)

- customer success execution (are expansions intentional or accidental?)

The Founder's perspective: NRR tells you whether the business is getting easier to grow. If NRR is rising, each cohort becomes more valuable and you can fund growth with less incremental acquisition. If NRR is falling, you're buying growth every month—usually with worse payback and more stress on cash.

NRR also helps you interpret other metrics:

- It influences LTV (Customer Lifetime Value) because expanding customers extend and increase the cash flows you get from an account.

- It affects CAC Payback Period because strong expansion can "pay back" CAC after the initial sale.

- It changes how you should read Burn Multiple—high burn is harder to justify when the base is shrinking.

How NRR is calculated

At its core, NRR compares ending recurring revenue from the starting customer set to starting recurring revenue.

Key rule: only include customers who existed at the start of the period in every component of the calculation.

What goes into each component

For a monthly NRR based on MRR:

- Starting recurring revenue: MRR from customers active on day 1 (see MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue)).

- Expansion: upgrades, add-ons, seat increases, higher usage charges that are treated as recurring (see Expansion MRR).

- Contraction: downgrades, seat reductions, partial removals (see Contraction MRR).

- Churn: lost MRR from customers who cancel or lapse (see MRR Churn Rate).

A close cousin is net churn:

And the relationship (when defined on the same base and period):

If you work primarily in annual terms, you can calculate NRR using ARR instead (see ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue)). For annual contracts and forward-looking commitments, some teams prefer CMRR (Committed Monthly Recurring Revenue) to better reflect contract reality.

A concrete example (with a sanity check)

Assume you start January with $100,000 in MRR from existing customers:

- Expansion: +$18,000

- Contraction: -$5,000

- Churn: -$12,000

Ending MRR from that same starting customer set is:

$100,000 + 18,000 - 5,000 - 12,000 = $101,000

NRR is:

So NRR = 101%.

Sanity check founders should internalize:

- If expansion equals churn + contraction, NRR is exactly 100%.

- If churn spikes but expansion doesn't move, NRR drops immediately.

- If expansions are lumpy (common in enterprise), monthly NRR can look noisy—use a trailing average like T3MA (Trailing 3-Month Average).

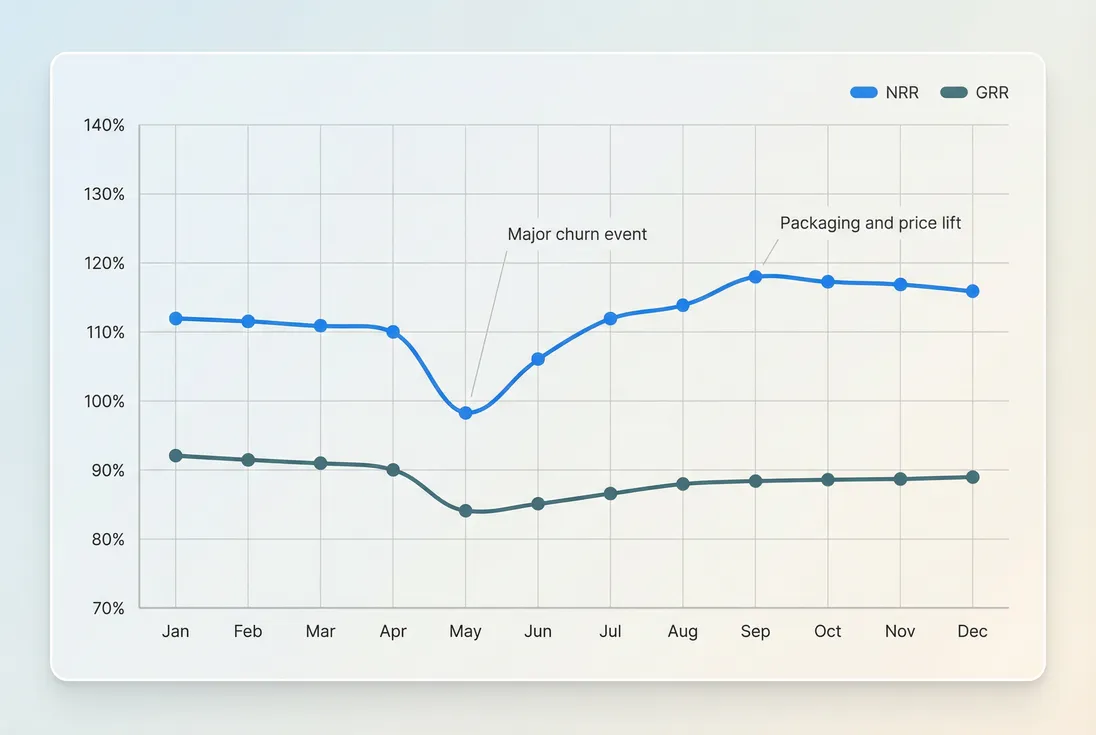

NRR vs. GRR (why both matter)

NRR can hide serious retention problems if expansion is strong. That's why you should pair it with GRR (Gross Revenue Retention), which ignores expansion:

Practical interpretation:

- High NRR + low GRR often means you're leaking customers but expanding a subset aggressively. That can be fine, or it can be a warning sign about product-market fit in parts of your base.

- High GRR + low NRR usually means customers stay but don't grow—often a packaging, pricing, or adoption ceiling.

What moves NRR up or down

NRR is not a "customer success metric." It's a business model metric that customer success, product, pricing, and sales all influence.

Expansion drivers (the "up" forces)

Common expansion sources:

- Seat growth (per-seat pricing): customers hire and add users (see Per-Seat Pricing).

- Usage growth: customers use more and pay more (see Usage-Based Pricing and Metered Revenue).

- Tier upgrades: customers move from Starter to Pro as needs mature.

- Add-ons and cross-sells: additional modules, compliance, analytics, extra environments.

- Price increases: expansion without increased usage—powerful but risky if value perception isn't there.

A useful discipline: separate "organic" expansion from "policy" expansion.

- Organic: seats/usage/features adopted because value increased.

- Policy: list price increases, discount roll-offs, contract true-ups.

Both raise NRR, but they have very different churn risks.

Retention and contraction drivers (the "down" forces)

NRR falls when:

- customers churn outright (voluntary or involuntary; see Voluntary Churn and Involuntary Churn)

- customers downgrade because value isn't realized, budgets tighten, or packaging mismatches

- you over-discount early and then can't renew at closer-to-list pricing (see Discounts in SaaS)

A founder-level diagnostic: when NRR drops, ask which lever failed first:

- Did churn rise?

- Did contraction rise?

- Did expansion slow?

- Or did the mix shift (fewer customers with expansion potential)?

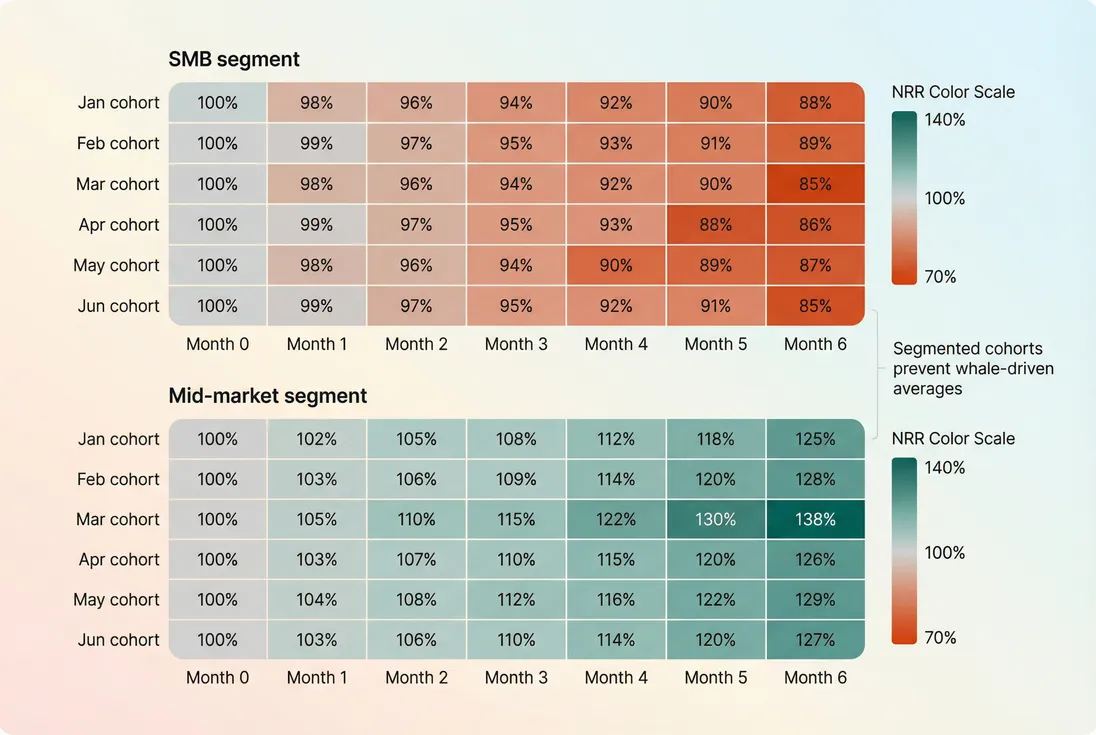

The "mix shift" trap

NRR is a weighted metric. A small number of large accounts can dominate it.

Two common cases:

- Whale uplift: one enterprise customer expands 3x; NRR looks great even while the rest of the base is flat.

- SMB dilution: you add many small customers with limited expansion paths; NRR may drift down even if the product is fine.

This is why you should segment NRR by account size (using ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account) or ASP (Average Selling Price)) and watch Customer Concentration Risk and Cohort Whale Risk.

NRR can rebound quickly with expansion motions, while GRR exposes whether you are actually stopping revenue leakage.

What "good" looks like in practice

Benchmarks vary by segment, contract structure, and expansion headroom. Use these as ranges to calibrate, not absolutes.

| Segment (typical motion) | Common NRR range | What usually drives it |

|---|---|---|

| SMB self-serve | 90%–110% | churn management + small upgrades |

| Mid-market hybrid | 100%–120% | seat growth, tier upgrades, CS-led expansion |

| Enterprise sales-led | 110%–140% | add-ons, expansions at renewal, true-ups |

Two practical founder rules:

- If you're sub-100% NRR, you're fighting gravity. Fix churn and contraction before scaling acquisition.

- If you're well above 110% NRR, you're probably sitting on an expansion engine—invest in it intentionally (playbooks, packaging, customer success capacity) while protecting GRR.

The Founder's perspective: Don't set an NRR target in isolation. Set a paired target: "GRR must stay above X while NRR rises to Y." That prevents you from "buying" NRR with aggressive expansions that increase churn risk or concentrate revenue in a few accounts.

How founders use NRR to make decisions

NRR becomes useful when you translate it into operating choices: where to invest, what to fix first, and what growth is actually sustainable.

1) Decide where to spend your next headcount

When NRR is low, the highest ROI roles are usually:

- lifecycle/onboarding to shorten time-to-value (see Time to Value (TTV))

- support and product work that reduces churn drivers

- billing ops to reduce involuntary churn (card retries, dunning)

When NRR is high but GRR is slipping:

- invest in churn prevention (renewal process, health scoring, better qualification)

- stop treating expansion as a substitute for retention

When NRR is high and stable:

- you can justify more spend on acquisition because the base compounds (tie this to payback in CAC Payback Period)

2) Pressure-test pricing and packaging changes

Pricing projects should be evaluated by their NRR impact across existing customers:

- Does the change raise expansion without creating a churn spike 60–120 days later?

- Are downgrades increasing because customers are "right-sizing" after a price lift?

- Are you relying on discount roll-offs (fragile) versus value-based expansion (durable)?

Use NRR segmentation to avoid broad mistakes: a price lift might improve enterprise NRR while hurting SMB churn.

3) Build a more realistic forecast

NRR is a shortcut for "base momentum." For many SaaS businesses:

- Next period ending recurring revenue ≈ current recurring revenue × NRR + new recurring revenue

That's not perfect (timing, cohorts, and seasonality matter), but it forces the right conversation: Is our growth plan dependent on new acquisition, or does the base carry part of the load?

If your base is shrinking (NRR < 100%), your forecast should explicitly show how much new MRR must "fill the hole" before growth begins.

4) Diagnose whether product adoption is working

If product usage and activation are improving but NRR is not, common explanations:

- customers are adopting features that don't map to monetization

- expansion paths are unclear (packaging problem)

- sales sold the wrong customers (mismatch shows up as contraction and churn)

Pair NRR with Feature Adoption Rate and Cohort Analysis to see whether newer cohorts retain and expand better than older cohorts.

Segmented cohort NRR shows whether expansion is structural (mid-market) or whether the base decays over time (SMB), which an overall average can hide.

When NRR breaks (and how to avoid bad decisions)

NRR is easy to miscompute and easy to misinterpret. These are the most common founder pitfalls.

Mixing customers into the denominator

NRR must be based on the starting customer set. Common errors:

- including new customers in "ending MRR"

- counting reactivated customers as expansion (better tracked separately; see Reactivation MRR)

- changing the cohort definition month to month

If you want a metric that includes reactivations, treat it as a separate view—not "NRR"—so everyone knows what's being measured.

Letting billing artifacts distort the picture

NRR should reflect recurring revenue reality, not invoice noise. Watch out for:

- refunds and credits (see Refunds in SaaS)

- chargebacks (see Chargebacks in SaaS)

- annual prepay timing and proration effects

- taxes and VAT treatment (see VAT handling for SaaS)

- one-time charges being incorrectly included (see One Time Payments)

If NRR swings when nothing operational changed, suspect data classification before you suspect your business.

Using NRR without concentration context

A "great" NRR number can be a mirage if it's driven by a handful of accounts. Protect yourself by reviewing:

- NRR by revenue decile (top 10% of accounts vs the rest)

- NRR excluding the top 1–3 accounts (a stress test)

- concentration metrics (see Customer Concentration Risk)

Over-optimizing NRR at the expense of GRR

It's possible to push upgrades so hard that you increase churn later (customers feel squeezed, or the product doesn't deliver incremental value). Use NRR as a growth metric, but use GRR as your "truth serum."

How to operationalize NRR in GrowPanel

If you want NRR to drive action, make it easy to review and segment:

- Use the Retention views to compare NRR and GRR trends over time (see Net Revenue Retention and Gross Revenue Retention).

- Use Cohorts to see whether newer customer groups retain and expand better (see Cohorts).

- Use MRR movements to confirm what's actually driving the change: expansion vs contraction vs churn (see MRR movements).

- Use Filters to segment by plan, customer size, country, or other attributes so you can find the real driver, not the average (see Filters).

The takeaway

NRR is the cleanest single percentage for answering: Are my existing customers becoming more valuable over time? But it only becomes a founder tool when you (1) calculate it from a stable starting cohort, (2) pair it with GRR, and (3) segment it enough to avoid being misled by mix and whales.

If you're deciding what to fix next: NRR below 100% is a retention emergency; NRR above 110% is an expansion opportunity—so long as GRR stays healthy.

Frequently asked questions

It depends on segment and motion. Self-serve SMB often lives around 90 to 110 percent, while mid-market aims for 100 to 120 percent. Enterprise companies with strong expansion can reach 120 to 140 percent. Treat benchmarks as directional; your target should reflect price model, cohort maturity, and concentration risk.

NRR only measures how last period customers changed. You can have 120 percent NRR but weak new acquisition, so total MRR grows slowly. You can also have high NRR concentrated in a few large accounts, masking churn elsewhere. Pair NRR with new MRR and customer concentration to avoid false confidence.

Use the cadence that matches renewal and expansion behavior. For SMB monthly plans, monthly NRR with a trailing 3-month average is practical. For annual contracts, quarterly or annual NRR is often more meaningful because upgrades and churn are lumpy. Consistency matters more than the exact window.

Most teams exclude reactivations from NRR to keep it a clean view of the same starting customer set. Reactivations are real revenue, but they behave more like a new sale with a different cycle. Track reactivation separately and use NRR to judge retention plus expansion of customers who never left.

Start by protecting gross retention: reduce time-to-value, fix involuntary churn, and tighten customer success around renewal risk. Then build intentional expansion: usage triggers, packaging that scales with value, and clear upgrade paths. Price increases can help, but only if adoption and perceived value support them.