Table of contents

Natural rate of growth

Founders obsess over new sales, but most SaaS outcomes are decided after the sale. The natural rate of growth tells you whether your current customers make your revenue base compound—or quietly decay—before you spend another dollar on acquisition.

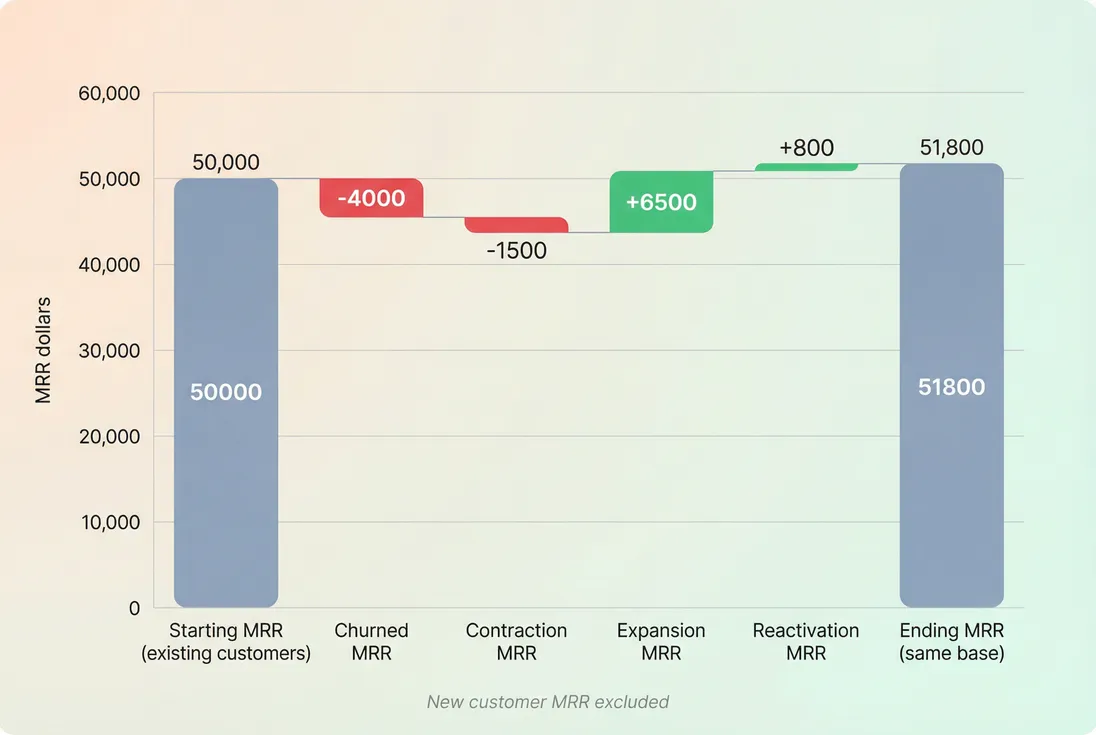

Natural rate of growth (NRG) is the percentage change in MRR coming only from your existing customers over a period, driven by expansion, contraction, churn, and (optionally) reactivations—excluding new customer MRR.

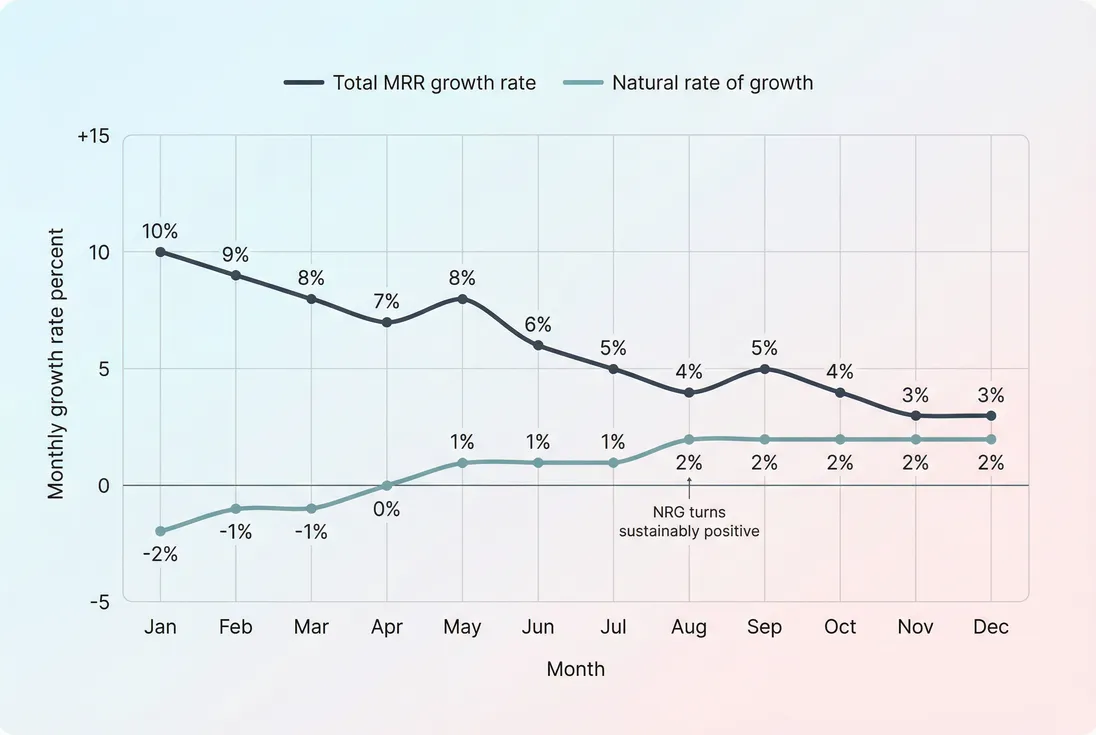

If NRG is positive, your installed base is a growth engine. If it's negative, you're running a leaky bucket and new sales are masking it.

What NRG reveals

NRG answers a practical question: If we stopped acquiring new customers today, would revenue from our current customers grow or shrink next month?

That makes it a "base health" metric, not a "go-to-market output" metric.

NRG is especially useful for:

- Diagnosing retention vs acquisition problems. Overall growth can look fine even while the installed base decays.

- Forecasting without over-crediting sales. If NRG is consistently negative, forecasts that assume "stable retention" will be too optimistic.

- Choosing where to invest. Positive NRG makes acquisition more scalable because every cohort you add tends to expand instead of leak.

The Founder's perspective

When NRG is negative, hiring more salespeople often makes dashboards look better while unit economics get worse. When NRG is positive and stable, you can push acquisition harder because each month's bookings become a compounding base instead of a treadmill.

How to calculate it

At its core, NRG isolates MRR movements within your existing customer base.

A common definition is:

Where:

- Starting MRR = MRR at the start of the period for customers already active then

- Expansion MRR = upgrades, added seats, usage increases that raise MRR (see Expansion MRR)

- Contraction MRR = downgrades, seat reductions, usage decreases that lower MRR (see Contraction MRR)

- Churned MRR = MRR lost from customers who cancel (see MRR Churn Rate)

- Reactivation MRR = previously churned customers returning (see Reactivation MRR)

Relationship to net MRR churn and NRR

If you use a definition of net churn that includes expansion and contraction (and may or may not include reactivation), you can think of NRG as the "mirror image":

- When net churn is negative (meaning expansion outweighs churn), NRG is positive.

- When net churn is positive, NRG is negative.

That's why it pairs naturally with Net MRR Churn Rate.

NRG is also closely related to NRR (Net Revenue Retention). In simple terms:

- NRR describes the ending revenue from the same starting cohort as a percent of starting revenue.

- NRG is the "rate" view of that same phenomenon over a period.

If your NRR for a month is 102%, your monthly NRG is roughly +2% (depending on exact inclusions like reactivation).

The one rule that prevents confusion

Do not include new customer MRR.

New customer bookings are important, but they answer a different question. For NRG you're measuring the "physics" of the installed base.

If you want total growth, use Revenue Growth Rate alongside NRG.

Practical calculation workflow

- Start with your MRR baseline (see MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue)).

- Pull movements for the period: churn, contraction, expansion, reactivation.

- Divide net movement by starting MRR.

If you track movements in a tool, you typically want a movements breakdown like MRR movements with the ability to segment using filters (for example by plan tier or acquisition channel). In GrowPanel, this aligns with MRR movements and Filters.

What drives NRG up or down

NRG is not magic. It's just the net effect of four forces. The value comes from understanding which lever is actually moving.

1) Expansion motion (product value compounding)

Expansion is your best kind of growth because it usually has:

- High margin (no incremental acquisition cost)

- Short cycle time (often self-serve or CS-assisted)

- Strong signaling (customers are getting more value)

Expansion tends to come from:

- Seat growth (especially with Per-Seat Pricing)

- Usage scaling (see Usage-Based Pricing)

- Plan upgrades and add-ons

- Pricing power realized at renewal or through packaging

A subtle but common driver: ARPA drift. If ARPA rises inside the base, NRG improves even if logo retention is flat (see ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account)).

2) Contraction (mis-fit or pricing pressure)

Contraction can mean customers are getting less value—or they are actively optimizing spend.

Watch for contraction spikes after:

- Pricing changes

- Seat-based pricing audits

- Feature gating or packaging changes

- Economic downturns that force usage reduction

Contraction can be "healthy" if it's concentrated in low-fit customers and leads to better retention, but persistent contraction usually predicts future churn.

3) Churn (the leakage that dominates everything)

Churn is the fastest way to destroy NRG. Even modest churn overwhelms expansion in many SMB SaaS businesses.

To interpret churn properly, separate:

- Voluntary Churn (customer chooses to leave)

- Involuntary Churn (payment failures, billing issues)

If NRG is falling, check whether churn is coming from:

- A specific cohort (see Cohort Analysis)

- A specific segment (SMB vs mid-market)

- A specific churn reason (see Churn Reason Analysis)

4) Reactivation (helpful, but easy to over-credit)

Reactivations can improve NRG, but they're often lumpy and operationally driven (win-backs, billing recovery, seasonal return). Treat them as a separate lever:

- If reactivation is doing the heavy lifting, the "core" base may still be weak.

- Use it as a bonus, not the foundation of your plan.

How founders interpret changes

NRG is most useful when you interpret direction and stability, not a single point estimate.

A simple interpretation grid

| NRG pattern | What it usually means | Typical next move |

|---|---|---|

| Positive and stable | Base is compounding | Invest in acquisition with confidence; pressure-test capacity and onboarding |

| Positive but volatile | Expansion and churn are both spiky | Segment by customer size; smooth with better lifecycle and renewal ops |

| Near zero | Base is flat | Decide whether to drive expansion (packaging/pricing) or improve retention |

| Negative and stable | You have a leaky bucket | Pause aggressive spend; fix churn/contraction; tighten ICP |

| Falling trend | Something changed recently | Look for a product, pricing, or support change; analyze cohorts by start date |

The Founder's perspective

I like NRG as a "permission metric." When it's consistently positive, you have permission to scale acquisition. When it's negative, the company is effectively borrowing growth from sales—eventually CAC rises and payback stretches.

Why a small change matters

Because NRG applies to your entire revenue base, even small improvements compound.

Example: Starting MRR is $200k.

- At -1% NRG, the base shrinks by ~$2k per month before new sales.

- At +1% NRG, the base grows by ~$2k per month "for free."

That's a $4k swing per month on day one, and it compounds as the base grows.

Separate "pricing events" from "true expansion"

NRG can jump after a price increase. That's not bad—pricing is real. But you should label it correctly:

- If NRG improved because customers adopted more seats/modules, that's usage/value expansion.

- If it improved because you raised prices, it's pricing expansion.

Both are valuable, but they imply different risks. Pricing-driven NRG can reverse if churn rises at renewal.

A good practice is to compare NRG movement with:

- Logo Churn (are more customers leaving?)

- GRR (Gross Revenue Retention) (are you losing more base dollars even before expansion?)

- ASP (Average Selling Price) and Discounts in SaaS (did packaging or discounting shift?)

How founders use NRG to make decisions

NRG becomes powerful when you use it to answer operational questions.

1) How hard can we push acquisition?

If NRG is positive, every cohort you acquire tends to become more valuable over time, which improves:

If NRG is negative, scaling acquisition often produces a misleading "growth" story while:

- payback stretches,

- margins get pressured by support costs,

- and you need ever-increasing pipeline to stand still.

Pair NRG with Burn Multiple and Burn Rate: positive NRG usually improves capital efficiency because less spend is required to maintain growth.

2) Should we prioritize retention or expansion?

NRG decomposes cleanly into two strategic levers:

- Retention: reduce churned MRR and contraction MRR

- Expansion: increase expansion MRR (and optionally reactivation)

If churn is the dominant negative driver, your highest ROI work is typically:

- onboarding and activation improvements (see Onboarding Completion Rate)

- reducing involuntary churn

- tightening ICP and qualification (see Go To Market Strategy)

If churn is controlled but NRG is still flat, the opportunity is often:

- packaging that creates a natural upgrade path

- moving customers to annual or higher tiers (watch Average Contract Length (ACL))

- aligning the product with expansion moments (teams, usage limits, compliance needs)

3) Are we actually product-led in outcomes?

PLG companies often have inherently higher NRG because expansion is embedded in usage. Sales-led companies can also have high NRG, but it usually requires deliberate account management.

If you're transitioning models (see Product-Led Growth and Sales-Led Growth), NRG is one of the quickest reality checks:

- If PLG is working, expansion should rise and churn should fall in self-serve cohorts.

- If it's not, NRG often stays negative even as top-of-funnel improves.

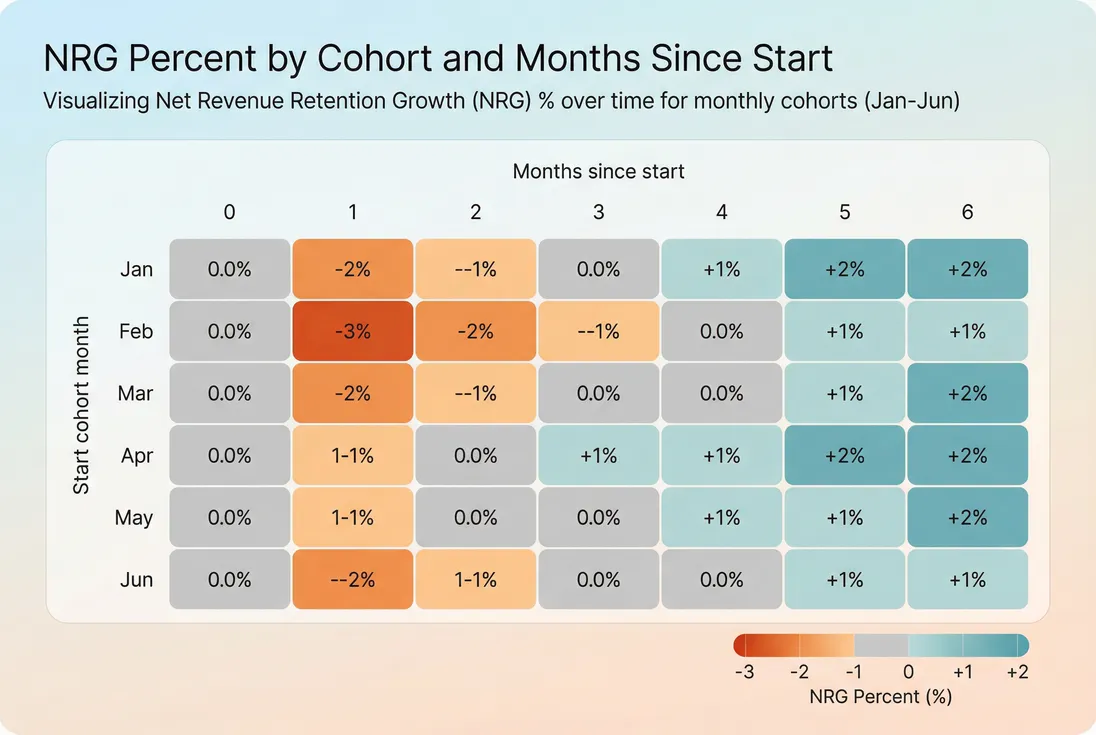

4) Which customers make NRG?

NRG is most actionable when segmented. The company-wide average can hide everything.

Segment NRG by:

- Plan tier

- Customer size (SMB vs mid-market vs enterprise)

- Acquisition channel

- Cohort start month

This is where cohort views matter: a strong overall NRG can be driven by a small number of expanding accounts, while newer cohorts are weak (see Cohort Whale Risk).

When NRG misleads

NRG is a strong metric, but founders get trapped when they forget what it assumes.

Early-stage denominator problems

If your starting MRR is small, a single churn or expansion event can swing NRG wildly. In the earliest stage:

- use a trailing average (for example a trailing 3-month average; see T3MA (Trailing 3-Month Average))

- focus on directional improvements, not precision

Annual billing and timing artifacts

If you recognize MRR changes at renewal points (common), NRG can look "chunky," especially with annual contracts. Two ways to reduce confusion:

- Ensure your MRR model spreads annual contracts appropriately (see MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue))

- Track NRG on a trailing basis (3-month or 6-month)

Also watch for billing-related effects like:

These don't change "product value," but they can change net revenue and customer behavior.

One-time expansion events

A single enterprise rollout can dominate expansion MRR and make NRG look amazing—until that account stabilizes.

If you suspect this:

- examine customer concentration (see Customer Concentration Risk)

- look at expansion distribution (median vs mean)

- sanity-check with Active Customer Count and logo retention

Reactivation masking churn

If you include reactivations in NRG, a strong win-back motion can hide high churn. That may be okay strategically, but you should label it:

- "Core NRG" = expansion minus contraction minus churn

- "Reported NRG" = core NRG plus reactivation

Benchmarks and targets (useful, not absolute)

Benchmarks depend heavily on pricing model and segment. Still, founders need practical ranges.

Typical monthly NRG ranges

| Model / segment | Weak | Healthy | Strong |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMB self-serve | below -1% | 0% to +1% | +1% to +3% |

| Mid-market | below -0.5% | +0.5% to +2% | +2% to +4% |

| Enterprise / seat-based | below 0% | +1% to +3% | +3% to +6% |

Use these as "smell tests," not goals. A company with high gross margin and short payback can tolerate lower NRG; a company with long payback needs stronger NRG or very low churn.

A practical way to operationalize NRG

You want NRG to become a weekly operating signal, not a quarterly post-mortem.

A simple cadence:

- Monthly: compute NRG and decompose it (churn vs contraction vs expansion vs reactivation).

- Monthly: segment by tier and cohort start month (see Cohort Analysis).

- Weekly: review churn reasons and leading indicators (activation, product adoption, support load).

- Quarterly: make one structural bet: pricing/packaging, onboarding, ICP tightening, or expansion motion.

The bottom line

Natural rate of growth is the cleanest way to separate two truths:

- How healthy your existing customer base is (do customers expand faster than they churn?)

- How much your growth depends on constant new sales (are you compounding or refilling?)

Track it alongside Net MRR Churn Rate, NRR (Net Revenue Retention), and Logo Churn. When NRG turns positive and stays there, scaling becomes simpler: every new cohort you add has a better chance of becoming an appreciating asset instead of a depreciating one.

Frequently asked questions

A healthy target is positive and stable. For many SMB SaaS businesses, +0.5 to +2 percent monthly is strong. Enterprise SaaS can be higher due to seat expansion. If it is negative, you are shrinking without new sales, which usually signals churn, downgrades, or weak expansion.

Revenue growth rate includes new customer revenue. Natural rate of growth excludes new customer MRR and focuses only on what happens inside your existing customer base: expansion, contraction, churn, and sometimes reactivation. It tells you whether the product naturally compounds or leaks, independent of acquisition spend.

They are closely related. Net MRR churn rate measures revenue lost net of expansion; natural rate of growth is the mirror image, showing net gain or loss from the installed base. If your definition excludes reactivations, natural rate of growth is roughly the negative of net MRR churn rate.

That usually means your existing customers are healthier, but new acquisition slowed or deal sizes dropped. Natural rate of growth is a base health metric; overall growth still depends on net new customers, pricing, and pipeline. Compare it alongside ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue) and new MRR trends.

First, quantify the drivers: churned MRR versus contraction MRR versus missing expansion. Then segment by plan, cohort, or customer size to find where leakage is concentrated. The goal is to stabilize retention and expansion before scaling acquisition; otherwise you are filling a leaky bucket.