Table of contents

LTV (Customer Lifetime Value)

Founders track LTV because it tells you whether growth is compounding—or leaking. If you spend $8k to acquire a customer who only produces $6k of gross profit before churn, scaling doesn't "fix" the business; it scales the loss.

LTV (customer lifetime value) is the total gross profit you expect to earn from a typical customer over the time they remain a paying customer. Good LTV work is less about a perfect number and more about knowing what levers (pricing, retention, expansion, gross margin) are actually moving it—and whether those moves are repeatable.

What LTV reveals

LTV is a unit economics "truth serum." It answers three practical questions:

How much can you afford to pay to acquire customers?

LTV is the ceiling for CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost). If your CAC approaches your gross profit LTV, you're buying revenue, not building an asset.Which customers are worth scaling?

Average LTV can hide that one segment is amazing and another is a churn machine. Founders use segmented LTV to decide which plans, industries, or channels to push.Which lever matters most right now?

LTV is driven by a small set of inputs. When LTV drops, you can usually trace it to one of: worsening retention, reduced expansion, pricing/discounting changes, or margin deterioration.

The Founder's perspective,

Treat LTV like a decision filter. If an initiative increases signups but reduces LTV (for example via heavier discounting or lower-quality customers), it might still be rational—but only if you understand the trade and can measure it.

Calculating LTV safely

There are many "LTV formulas." Most disagreements are not about math—they're about assumptions.

The practical baseline formula

A common, workable starting point in SaaS is:

- ARPA: average revenue per account (link: ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account))

- Gross margin: gross profit as a percent of revenue (link: Gross Margin)

- Expected lifetime: how long customers stick around (link: Customer Lifetime)

If you model customer lifetime from a steady monthly logo churn rate (for more on this topic, see How to calculate the lifetime of customers in SaaS):

So the "quick LTV" is:

This version is useful because it's interpretable: LTV rises when ARPA rises, when margin improves, or when churn falls.

A concrete example

Assume:

- ARPA = $120 per month

- Gross margin = 80%

- Monthly logo churn = 3%

Interpretation: the "average" customer produces about $3.2k of gross profit over their lifetime under these assumptions.

Want to estimate LTV for your own business? Use the free LTV calculator to model different ARPA, churn, and margin scenarios.

When the baseline works—and when it doesn't

The baseline formula is most reliable when:

- You have stable churn (not wildly different for new vs mature customers).

- Expansion exists but isn't extremely spiky.

- Your customer base is not split into radically different segments.

It breaks down when:

- You have meaningful expansion (NRR materially above GRR).

In that case, churn alone understates LTV because retained customers tend to pay more over time. Use NRR (Net Revenue Retention) and cohort revenue curves to model it. - Churn is front-loaded (common in SMB/PLG).

A single monthly churn rate averages "early churners" and "sticky survivors" and can mislead. - You sell annual contracts with renewals and step-ups.

A monthly churn approximation can be fine, but cohort retention is usually clearer.

The Founder's perspective,

The point of "quick LTV" is speed: you want a number good enough to decide whether to push acquisition or fix retention. Once you're spending meaningfully on growth, graduate to cohort-based LTV by segment.

What to include in LTV

The biggest LTV mistake is treating it like a universal standard. You need to pick a definition that matches the decision.

Revenue LTV vs gross profit LTV

- Revenue LTV: how much revenue you collect from a customer over their lifetime.

- Gross profit LTV: revenue LTV multiplied by gross margin (or contribution margin, if you allocate more costs).

For acquisition decisions, gross profit LTV is usually the correct basis because it matches the cash you can reinvest.

Use revenue LTV primarily when:

- You're comparing retention patterns across plans,

- Or you're doing a high-level valuation story (and you separately address margin).

Don't ignore "small" revenue reducers

A few items commonly distort LTV if you ignore them:

- Discounting and coupons (link: Discounts in SaaS)

- Refunds (link: Refunds in SaaS)

- Billing fees if they are material at your price point (link: Billing Fees)

If you discount aggressively to "buy" growth, LTV may appear stable while payback quietly worsens.

Segment LTV or you will optimize the wrong thing

A single LTV number is rarely operationally useful. At minimum, segment by:

- Plan / price point (link: ASP (Average Selling Price))

- Acquisition channel or motion (Product-Led Growth vs Sales-Led Growth)

- Customer size band (SMB, mid-market, enterprise)

- Geo or billing currency if pricing differs materially

If you have a few large customers, also watch concentration effects (link: Customer Concentration Risk).

What actually drives LTV

Most LTV movement is explained by four drivers. If you get these right, the rest is refinement.

Retention (logo churn and renewal behavior)

Retention is usually the biggest lever because it compounds: the longer customers stay, the more months they pay, the more likely they expand, and the more efficient support becomes.

Track retention directly with:

- Customer Churn Rate

- Logo Churn

- Cohorts (link: Cohort Analysis)

Also separate:

- Voluntary churn (bad fit, low value, competitors) vs Voluntary Churn

- Involuntary churn (failed payments) vs Involuntary Churn

If LTV is falling, ask: "Did churn worsen for new cohorts, or did we change who we're acquiring?"

Pricing and ARPA (and discount discipline)

ARPA lifts LTV—if it doesn't cause churn to rise enough to offset it.

Two founder-relevant patterns:

- Price increases often raise LTV more than you think, because gross margin on incremental price is usually high.

- Discounting can quietly crush LTV if it's targeted at customers who were already likely to buy.

Expansion and contraction

Expansion raises LTV, but it's not "free." It typically requires:

- The right packaging and pricing (link: Per-Seat Pricing or Usage-Based Pricing)

- A product that scales with customer value

- Success motions that drive adoption

Expansion should show up in:

If NRR is high but LTV still looks weak, you may have "whale-driven" expansion. Check the risk (link: Cohort Whale Risk).

Gross margin and servicing cost

Founders often treat gross margin as static. It's not—especially with:

- AI-heavy inference costs,

- High-touch onboarding/support,

- Usage-based infrastructure exposure.

Even a few margin points matter because margin multiplies the entire revenue stream in LTV.

Using LTV to run the business

LTV is only useful when it changes decisions. Here's how founders actually use it.

Setting CAC limits and payback targets

Pair LTV with:

To quickly model different scenarios, try the CAC to LTV ratio calculator.

A simple operating logic:

- If payback is too long, you become funding-dependent.

- If LTV:CAC is too low, scaling burns cash without building value.

- If LTV:CAC is extremely high and growth is slow, you may be under-investing in acquisition.

| Situation | What it usually means | Typical action |

|---|---|---|

| LTV:CAC < 2x | Acquisition is too expensive or retention is weak | Fix churn/activation, raise prices, tighten targeting |

| LTV:CAC around 3x | Often workable unit economics | Scale cautiously, keep improving retention |

| LTV:CAC > 5x with slow growth | Potential under-spend or too strict targeting | Increase spend, test new channels, expand TAM focus |

Use ratios as signals, not absolutes. In fast-changing channels, you want buffer.

The Founder's perspective,

If you can't explain why LTV went up or down in one sentence (churn, ARPA, expansion, margin), you don't really have an LTV number—you have a spreadsheet artifact.

Prioritizing retention work that pays back

Because churn changes often dwarf other levers, LTV helps you justify retention investments that otherwise look "non-growth."

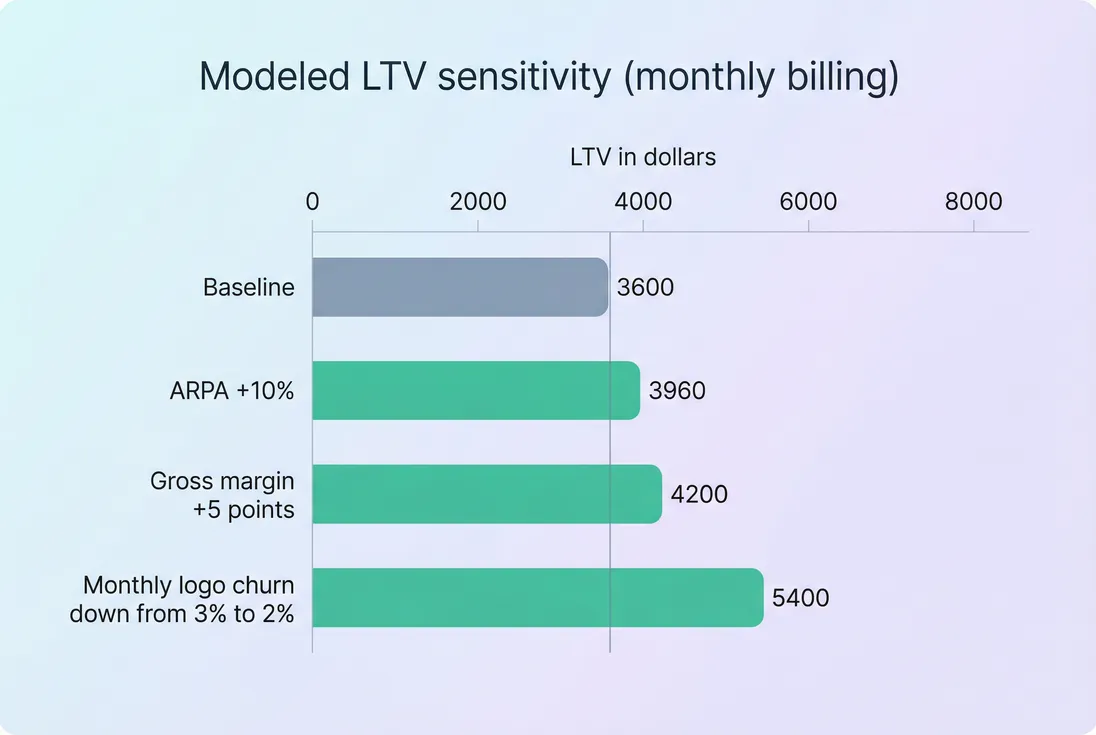

Example: If reducing monthly churn from 3% to 2% increases LTV by ~50% (as in the chart), that can support:

- Better onboarding (link: Time to Value (TTV))

- Improving early activation (link: Onboarding Completion Rate)

- Fixing reliability issues (link: Uptime and SLA)

- Systematic churn root cause work (link: Churn Reason Analysis)

Choosing the right growth motion

LTV differs by motion:

- PLG often has lower CAC but higher early churn (front-loaded retention risk).

- SLG often has higher CAC but better retention and expansion potential.

Use LTV to decide whether you should:

- Push harder on self-serve acquisition,

- Invest in sales capacity,

- Or narrow to a segment where retention is structurally higher.

Deciding whether to change pricing

Pricing tests should be evaluated on LTV impact, not only conversion.

A pricing move is good when:

- ARPA rises,

- churn does not worsen materially,

- expansion remains healthy,

- and gross margin doesn't degrade (for example via expensive feature usage).

If you run usage-based pricing, watch that increased ARPA isn't offset by increased COGS.

Cohort-based LTV (when you need accuracy)

Once you have enough history and you're spending meaningfully on acquisition, move beyond single-rate churn.

Cohort-based thinking uses actual retention and revenue behavior over time:

- How many customers are still active each month?

- How revenue per retained customer changes (expansion/contraction)

- How gross margin behaves with scale

This approach is also how you avoid false confidence from averages. A "quick LTV" might improve because the customer mix shifted; cohort curves tell you whether the product and onboarding actually improved.

If you want to operationalize this in reporting, use an LTV view that can be segmented and cross-checked against retention and cohorts. GrowPanel's subscription analytics provides LTV alongside the metrics you need to understand what's driving it. See the docs for more: LTV, Cohorts, Filters.

Interpreting LTV changes without fooling yourself

When LTV moves, don't stop at "up" or "down." Force attribution.

If LTV increases

Common "good" reasons:

- Lower churn in recent cohorts (verify with cohort retention)

- Higher ARPA from packaging or pricing changes

- Higher expansion (verify with NRR and expansion MRR)

- Better gross margin (lower infra/support costs)

Common "not actually good" reasons:

- Mix shift toward bigger customers (may be fragile)

- A few large expansions (whale-driven)

- Temporary discount pullback that hurts new bookings later

If LTV decreases

Common reasons:

- Higher early churn due to acquisition quality drop

- Discounting to hit top-line targets

- Support/infrastructure costs rising faster than revenue

- More contraction (customers downshifting)

Your debugging checklist:

- Did logo churn worsen? (link: Logo Churn)

- Did revenue retention change (GRR/NRR)? (links: GRR (Gross Revenue Retention), NRR (Net Revenue Retention))

- Did ARPA change due to pricing/discounting? (link: ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account))

- Did gross margin shift due to COGS? (link: COGS (Cost of Goods Sold))

Common failure modes

Treating churn as constant

In many SaaS businesses, churn is highest in months 1–3 and much lower later. A single monthly churn rate can understate the value of customers who make it past onboarding—and overstate the value of low-fit customers you're acquiring now.

Fix: lean on cohort retention and separate new-customer retention from mature retention.

Mixing segments into one average

If self-serve customers churn fast and sales-led customers expand, average LTV tells you almost nothing.

Fix: compute LTV by segment (plan, channel, size) and make growth decisions per segment.

Using revenue LTV for CAC decisions

Revenue LTV can look healthy while gross profit LTV is mediocre (especially with usage-heavy products).

Fix: base acquisition budgets on gross profit LTV or contribution margin LTV.

Ignoring cash dynamics

LTV is not cash in the bank. If payback is long, you can still run out of runway (link: Runway and Burn Rate).

Fix: always pair LTV with payback and burn efficiency (link: Burn Multiple).

A simple operating cadence for founders

If you want LTV to drive action, make it part of a recurring review:

- Monthly: review LTV and its drivers by segment (ARPA, churn, margin).

- Monthly: sanity-check with retention and cohorts (are new cohorts improving?).

- Quarterly: revisit pricing and packaging assumptions; confirm expansion is broad-based, not whale-driven.

- Before scaling spend: re-check CAC, payback, and LTV:CAC in the same view.

The Founder's perspective,

Your goal is not to "get LTV right." Your goal is to prevent growth decisions that depend on a fragile assumption. A simple, explainable LTV with strong segmentation beats a complex model nobody trusts.

Summary

LTV is the gross profit value of a customer relationship. It matters because it sets the economic boundaries for CAC, pricing, and retention investment. Start with a simple, driver-based model, then graduate to cohort-based LTV as you scale. Most importantly: segment it, attribute changes to real drivers, and use it to choose where to spend time and money.

Frequently asked questions

LTV is only meaningful relative to what it costs you to acquire and support customers. Compare it to CAC and payback. As a rule of thumb, you want enough LTV headroom to survive channel changes, pricing pressure, and churn shocks. Segment LTV by plan and channel before judging it.

Use gross profit LTV for most SaaS decisions. Revenue-only LTV exaggerates how much you can afford to spend on acquisition because it ignores hosting, support, and other COGS. If your COGS varies by segment or usage, gross profit LTV is essential for deciding which customers are actually worth scaling.

Many healthy SaaS businesses target an LTV:CAC of roughly 3x or higher, but the right number depends on growth rate, payback expectations, and retention stability. A high ratio can also mean you are under-investing in growth. Always pair the ratio with CAC payback and retention trends.

Early-stage LTV is mostly a hypothesis. Use short-term retention and cohort trends to estimate direction, not precision. If you only have a few months of data, a small churn change can double or halve modeled LTV. Focus on improving activation and early retention first, then revisit LTV once cohorts mature.

Expansion increases LTV, but only if it shows up consistently in cohort revenue retention. If expansion is driven by a few whales, average LTV can look great while most customers still churn quickly. Track expansion with NRR and cohort curves, and compute LTV by segment so upgrades do not hide weak retention.