Table of contents

GRR (Gross Revenue Retention)

GRR is the metric that tells you whether your revenue base is quietly eroding while you celebrate new sales. If you're growing, bad GRR gets masked by new bookings. If you're not growing, bad GRR is the reason you feel like you're running uphill.

Gross revenue retention (GRR) is the percentage of starting recurring revenue you keep from your existing customers over a period after churn and downgrades, and before any expansion.

What GRR reveals (and what it hides)

GRR answers one founder-grade question: How much of my existing revenue is "durable"? It's the cleanest view of retention because it doesn't let upsells cover up churn.

- High GRR means your core product delivers steady value and customers aren't downgrading or leaving.

- Low GRR means your base is leaking—usually from onboarding gaps, weak activation, poor support, bad-fit acquisition, or packaging/pricing issues.

What GRR doesn't tell you:

- Whether accounts are expanding (that's what NRR (Net Revenue Retention) is for).

- Whether churn is concentrated in a segment (you need segmentation and cohorts).

- Whether the issue is logos vs dollars (pair it with Logo Churn or logo retention).

The Founder's perspective

If your GRR is weak, you're funding a leaky bucket. That changes priorities: you don't "optimize CAC" first—you stop the revenue bleed so every new dollar you acquire actually sticks.

How GRR is calculated

At its simplest, GRR is retained recurring revenue from the starting customer set divided by starting recurring revenue.

Where:

- Starting recurring revenue: recurring revenue from customers active at the start of the period (often MRR; sometimes ARR).

- Churned revenue: revenue lost from customers who fully cancel.

- Contraction revenue: revenue lost from customers who stay but pay less (downgrades, seat reductions, discounting at renewal).

Important rule: Expansion is excluded. If a customer upgrades, that upgrade should not "rescue" GRR.

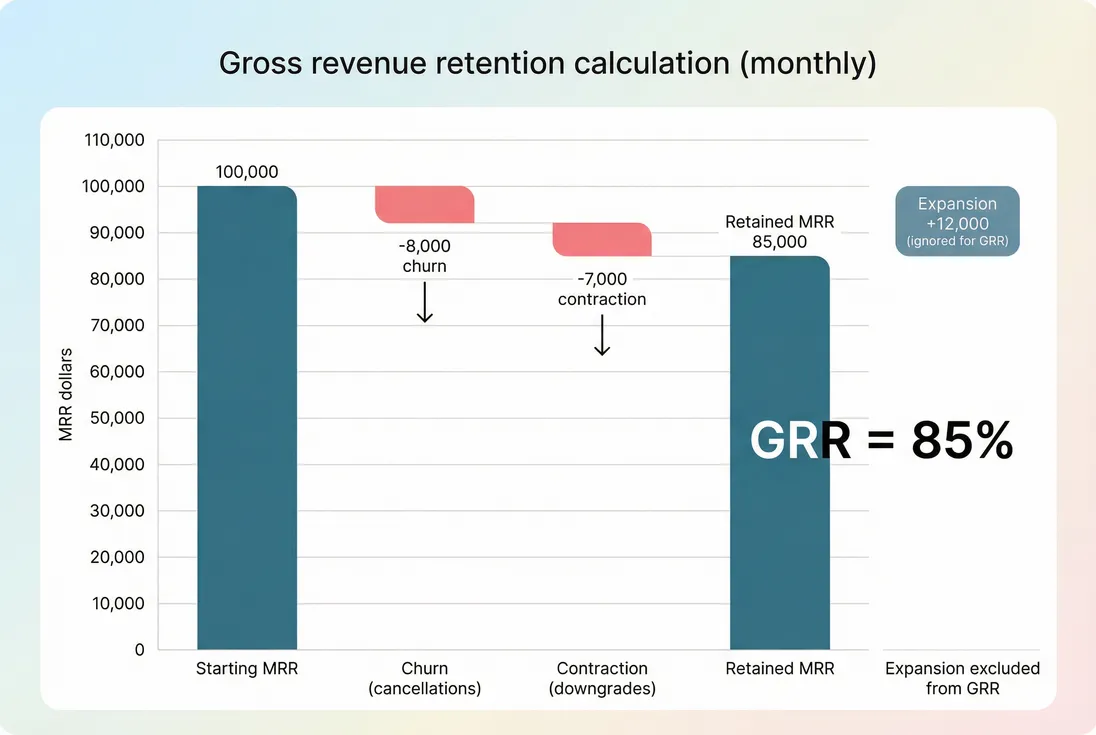

A concrete example

You start the month with $100,000 in MRR from existing customers.

During the month:

- $8,000 MRR churns (customers cancel)

- $7,000 MRR contracts (downgrades)

- $12,000 MRR expands (upsells)

GRR ignores the $12,000 expansion:

- Retained MRR = $100,000 − $8,000 − $7,000 = $85,000

- GRR = $85,000 / $100,000 = 85%

The cleanest mental model: "cap at the start"

When calculating GRR customer-by-customer, a helpful rule is: each customer can contribute at most their starting revenue. If they expand, you still count only up to their starting amount for GRR. If they shrink, you count the smaller amount.

This prevents accidental inflation when customers upgrade mid-period.

Where founders get GRR wrong

GRR is straightforward—but implementation details create misleading numbers. These are the most common traps:

Mixing new revenue into the cohort

GRR is always based on a fixed starting set of customers. New customers acquired during the period should contribute zero to GRR.

If you want a metric that includes everything, that's revenue growth rate—not retention.

Including expansion "because it's real revenue"

It is real revenue, but it belongs in NRR (Net Revenue Retention) or Expansion MRR. If you include expansion in GRR, you lose the signal founders need: how much pain your customers are in before upsells.

Confusing churn timing

If a customer cancels on the 5th but remains paid through the end of the month, are they churned "now" or at term end? You need consistency. If you're unsure, align your definition with your churn policy (see When should you recognize churn in SaaS?).

Letting refunds distort retention

Refunds can behave like negative revenue and can whipsaw GRR if you treat them as churn without aligning to cancellation events. If refunds are common, you should separately monitor Refunds in SaaS and ensure your retention logic matches your billing reality.

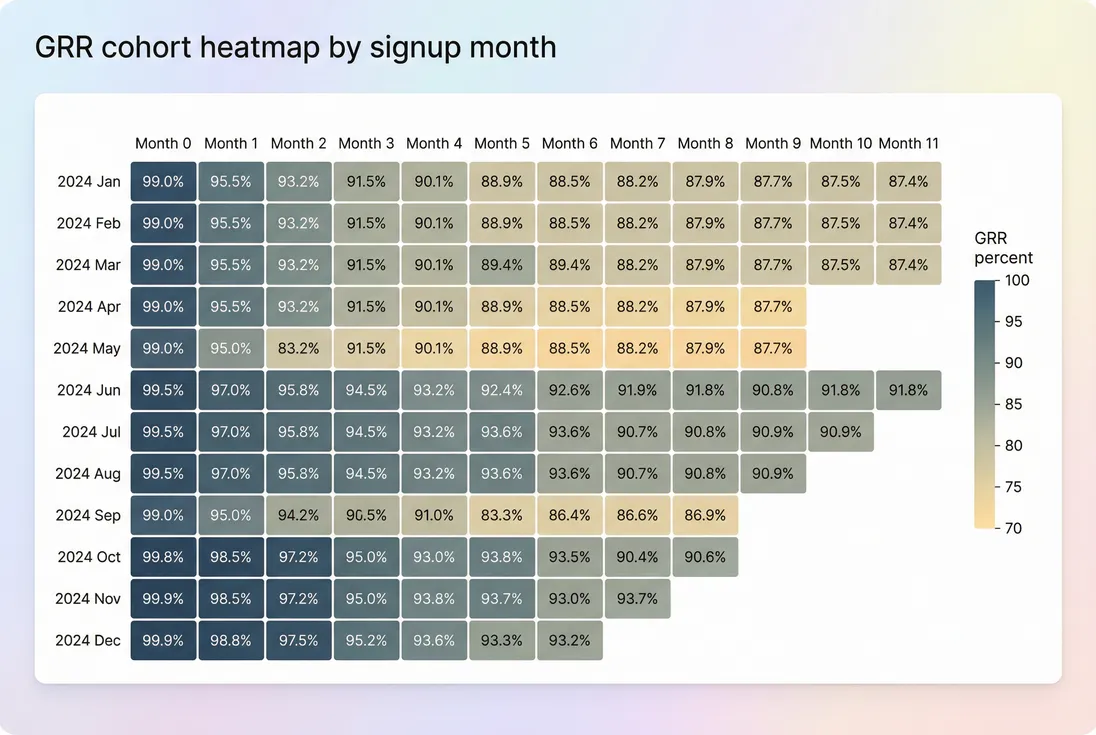

Not segmenting (the silent killer)

A "fine" overall GRR can hide a serious issue:

- Self-serve GRR might be 82% while mid-market is 95%.

- One plan tier might be bleeding due to pricing/packaging mismatch.

- A single acquisition channel might be bringing low-fit customers.

Segmentation is not optional if you want GRR to drive action.

The Founder's perspective

Overall GRR is for the board slide. Segmented GRR is for running the business. If you can't tell which plan, channel, or customer size band is driving contraction, you're guessing where to invest.

What drives GRR in real businesses

GRR only moves when churn or contraction moves. That sounds obvious—until you map those losses to operational causes.

Drivers of churn (full cancellations)

Common root causes:

- Slow time to value (customers never reach the "aha" moment)

- Missing core workflow features

- Reliability issues (see Uptime and SLA)

- Poor support responsiveness or onboarding

- Bad-fit acquisition and unclear positioning (see Go To Market Strategy)

How founders typically act:

- Fix onboarding and activation (see Time to Value (TTV) and Onboarding Completion Rate)

- Improve lifecycle messaging and adoption nudges (see Feature Adoption Rate)

- Reduce avoidable churn (see Involuntary Churn)

Drivers of contraction (downgrades)

Contraction often points to a different set of problems:

- Seats/usage drop because the product isn't embedded in workflows

- Packaging doesn't match value delivered

- Customers "optimize" spend during budget cuts

- Discounting pressure at renewal

Contraction is especially important because it can be a leading indicator: customers downgrade before they cancel.

A practical way to diagnose contraction:

- If contraction clusters in the first 90 days, it's onboarding/value.

- If contraction clusters at renewal, it's pricing/value communication, competitive pressure, or procurement.

For pricing context, see Per-Seat Pricing, Usage-Based Pricing, and Discounts in SaaS.

How to interpret GRR changes

GRR is most useful when you treat it like an operational KPI with thresholds—not a vanity benchmark.

Directional meaning

- GRR down (e.g., 92% → 88%): you're losing more baseline revenue to churn and downgrades. Expect slower growth unless acquisition or expansion increases to compensate.

- GRR up (e.g., 88% → 92%): your base is stabilizing. Sales efficiency and payback typically improve because less new revenue is needed to offset losses.

Tie GRR changes to the "why," not just the "what":

- Pair it with MRR Churn Rate to see loss velocity.

- Pair it with Churn Reason Analysis to see root causes.

- Pair it with Cohort Analysis to see whether the problem is new cohorts or your whole base.

A useful comparison table

| Metric | Includes churn | Includes contraction | Includes expansion | Best for |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GRR | Yes | Yes | No | Product durability, "leaky bucket" detection |

| NRR | Yes | Yes | Yes | Account growth, expansion motion strength |

| Logo retention | Yes (logos) | No | No | Product-market fit and customer targeting quality |

(For logo-level measurement, also track Customer Churn Rate and Logo Churn.)

Benchmarks (use carefully)

Benchmarks vary by segment, contract length, and maturity. Still, founders need ranges to calibrate urgency:

| Business type | Typical GRR range | What it usually implies |

|---|---|---|

| Early self-serve SMB | 80–90% monthly | Onboarding and activation dominate retention |

| Strong SMB / prosumer | 90–95% monthly | Solid value, watch contraction and support load |

| Mid-market | 90–96% (monthly equivalent) | Packaging, renewals process, and CS motion matter |

| Enterprise | 92–97% (often annual lens) | Renewal execution and product breadth drive results |

| Best-in-class | 95%+ | Low churn and low contraction; strong retention moat |

Use benchmarks to set priorities, not to claim you're "good."

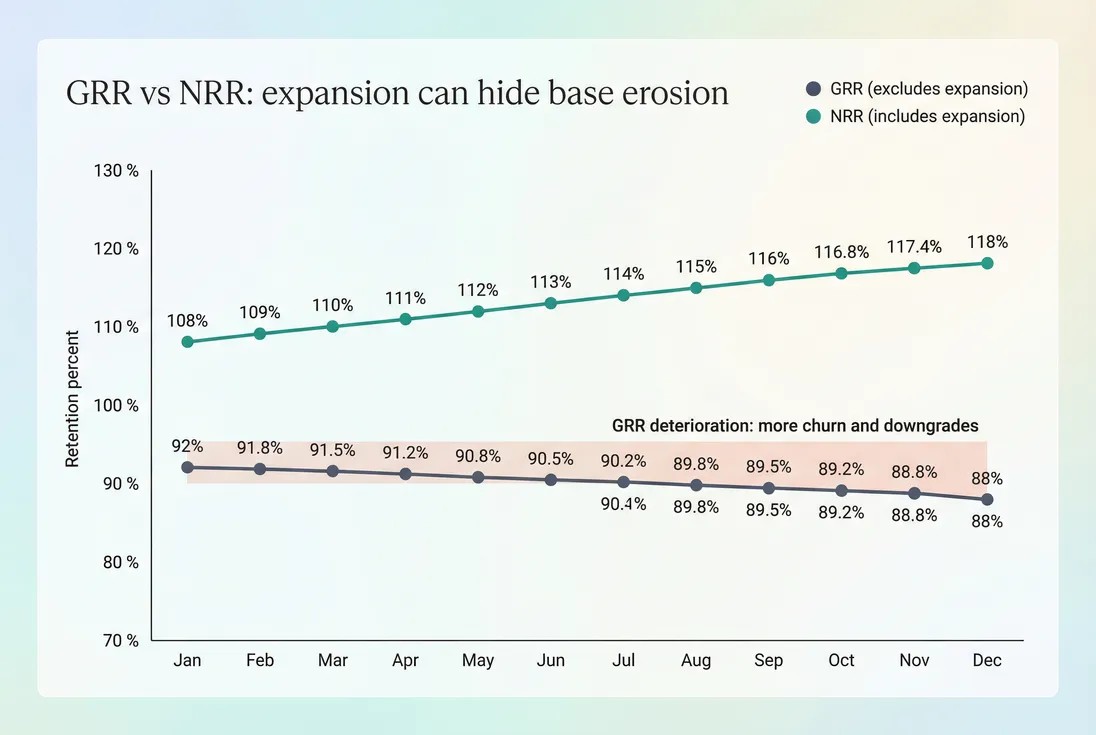

GRR vs NRR: why you need both

If GRR is "how much revenue you kept," NRR is "how much you grew the accounts you kept."

A healthy pattern in many strong companies:

- GRR is stable (durability)

- NRR rises (expansion motion improves)

A dangerous pattern:

- NRR looks great, but GRR is slipping

This means expansion is masking churn and downgrades. If expansion slows (budget cuts, saturation, competition), growth can fall off a cliff.

How founders use GRR to make decisions

GRR becomes powerful when it drives concrete tradeoffs: product, pricing, and customer success capacity.

1) Set an "acceptable leak" threshold

Decide what GRR floor triggers action. Example:

- Below 90% monthly GRR: pause scaling acquisition, prioritize retention sprint(s)

- 90–93%: targeted fixes (payments, onboarding, packaging)

- Above 93%: focus shifts toward expansion and efficient growth

This is not dogma; it's a forcing function for focus.

2) Segment GRR to find the real problem

Minimum segmentation that pays off:

- By plan tier (packaging mismatch shows up here)

- By customer size (SMB vs mid-market behavior differs)

- By acquisition channel (bad-fit lead sources surface fast)

- By tenure (0–90 days vs mature customers)

Cohorts make this even clearer because they separate "we improved" from "we just got lucky."

3) Evaluate pricing and packaging risk

Any pricing change has two GRR risks:

- Downgrades (contraction) if customers choose a smaller plan

- Cancellations if value doesn't justify the new price

Before rolling out a change broadly:

- Pilot on a segment

- Monitor contraction separately from cancellations

- Compare cohort GRR before/after the change

Pair GRR with ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account) and ASP (Average Selling Price) to understand whether you're trading higher prices for weaker retention.

4) Plan customer success coverage

GRR can justify headcount when it's tied to recoverable losses. Example logic:

- If downgrades are concentrated in accounts without onboarding support, a CS hire may pay for itself quickly.

- If churn clusters around time-to-value, invest in onboarding flow and education content first.

Tie this to unit economics using LTV (Customer Lifetime Value) and acquisition constraints like CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost) and CAC Payback Period.

The Founder's perspective

When GRR is low, every "growth" plan is actually two plans: acquire customers and replace the revenue you lost. Improving GRR is often the fastest way to improve capital efficiency, because it reduces the replacement tax on sales and marketing.

Operationalizing GRR (so it stays trustworthy)

Define your GRR spec in writing

Founders get into trouble when "GRR" changes depending on who pulled the report. Write down:

- Period: monthly, quarterly, trailing twelve months

- Revenue basis: MRR/ARR, billed vs contract vs recognized

- Churn timing rule: cancellation date vs end-of-term

- Treatment of: downgrades, pausing, credits, refunds, reactivations

If you handle complicated billing, keep related hygiene metrics nearby (e.g., Accounts Receivable (AR) Aging and Deferred Revenue).

Use revenue movement breakdowns

To improve GRR, you need the loss components:

- churned revenue

- contraction revenue

In GrowPanel, this is typically approached through retention and MRR movements, with segmentation via filters:

Build a simple weekly GRR review

A lightweight operating cadence for busy founders:

- Check overall GRR trend (last 8–12 weeks).

- Identify top churn and contraction events by dollars (whales first).

- Slice by plan and tenure to find "new customer" vs "mature base" issues.

- Pull 5–10 accounts from the customer list and read the story (why did they leave or downgrade?).

(If you're seeing whale-driven volatility, also monitor Cohort Whale Risk and Customer Concentration Risk.)

The decision rule to remember

If you remember one thing: GRR tells you whether your revenue base is structurally stable without relying on upsells. Improving it reduces the replacement burden on growth, makes forecasts more reliable, and usually improves capital efficiency across the board.

When GRR drops, treat it like a product and customer success incident—not a reporting detail.

Frequently asked questions

For SMB-focused SaaS, monthly GRR in the high 80s to low 90s is common; best-in-class is mid to high 90s. For enterprise SaaS with annual contracts, GRR often lands 90–97%. Use segmentation: if self-serve is 85% and mid-market is 95%, you have a packaging and onboarding gap.

No. GRR ignores expansion and counts only revenue you kept from the starting customer set, after churn and downgrades. It is capped at 100%. If you are seeing GRR over 100%, your definition is actually NRR or you are accidentally including expansion, reactivations, or new customer revenue in the numerator.

Track both, but for different decisions. Monthly GRR is your operational early-warning system for churn and downgrades. A trailing twelve-month GRR smooths seasonality and aligns with board and investor conversations. If you sell annual contracts, also track renewal-period GRR by renewal cohort to avoid misleading monthly noise.

Discounts reduce retained revenue if they apply to renewals or downgrades, so GRR should reflect them. Refunds can create "false churn" if treated as negative revenue without aligning to cancellation timing. The key is consistency: define whether GRR is based on billed MRR, contract MRR, or recognized revenue, and apply the same rules every period.

Start with the biggest, most preventable losses: involuntary churn (payment failures), short-tenure churn (first 30–90 days), and plan downgrades caused by packaging mismatch. Then improve retention drivers: time to value, onboarding completion, and support responsiveness. Use churn reason analysis to target one dominant driver at a time.