Table of contents

Expansion MRR

Founders care about Expansion MRR because it's the cleanest signal that customers are getting more value over time—and that your growth can come from the base you already paid to acquire. When Expansion MRR is strong, you can grow with less reliance on new logo volume, shorter payback, and more predictable planning.

Expansion MRR is the increase in Monthly Recurring Revenue coming from existing customers during a period, excluding new customers and reactivations. It includes upgrades, add-ons, seat increases, usage tier increases, and sometimes price uplifts—anything that raises recurring revenue from customers who were already paying at the start of the period.

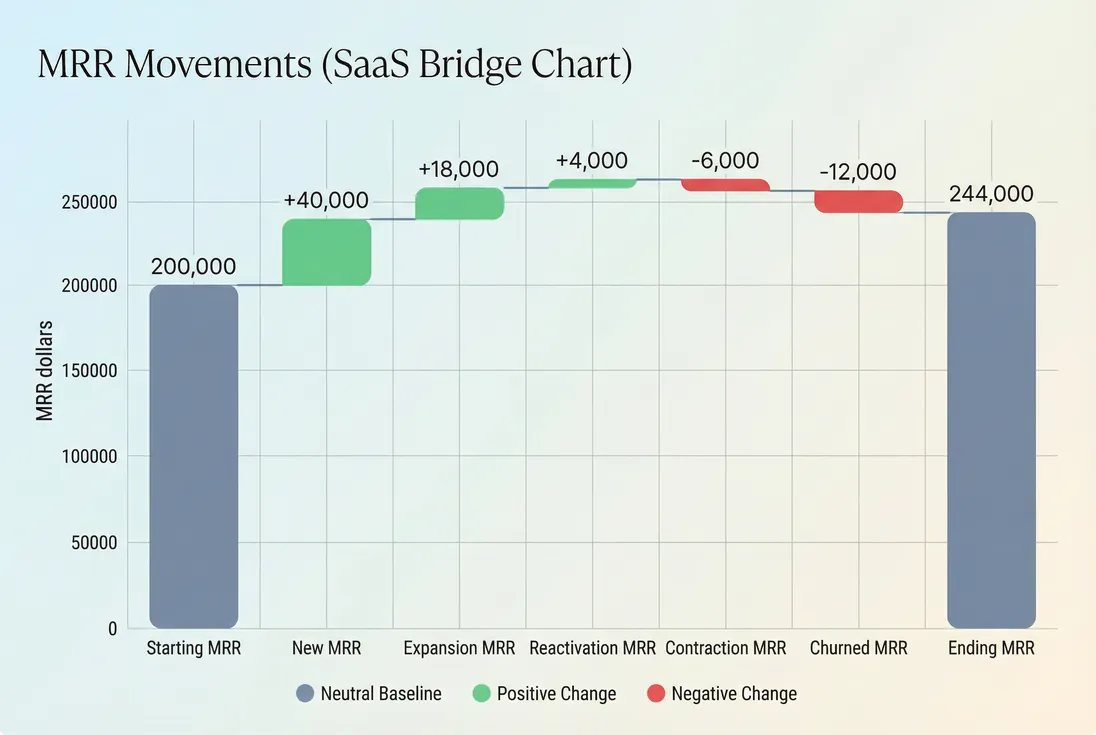

Expansion MRR is one of the core building blocks of ending MRR, and it's the part that usually reflects growing customer value rather than acquisition volume.

What counts as expansion MRR

Expansion MRR is not "upsells" in the sales sense. It's strictly dollar movement in recurring revenue among customers who were already active.

Typical sources:

- Plan upgrades: Basic → Pro

- Seat growth: 10 seats → 25 seats (see Per-Seat Pricing)

- Add-ons: security pack, additional workspace, premium support (if billed recurring)

- Usage tier increases: moving up a tier in Usage-Based Pricing

- Billing interval change: changing from yearly to monthly payment may increase MRR, but in fact it's a early warning sign that the customer is considering churning.

- Price uplift: renewal repricing or list price increase (depending on how you classify it)

What should not count:

- New customer MRR (covered in overall MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue))

- Reactivations (track separately as Reactivation MRR)

- One-time charges (implementation, overages that aren't recurring—see One Time Payments)

- Refunds and chargebacks (separate operational noise; see Refunds in SaaS and Chargebacks in SaaS)

A practical founder rule: if you can't point to a repeatable product/packaging mechanism (seats, tiers, add-ons, usage tiers, repricing policy), don't treat it as true expansion.

The Founder's perspective

If Expansion MRR is coming mostly from one-off renegotiations, it's not a growth engine—it's deal-making. You'll forecast it wrong, hire wrong, and be surprised by churn. If it's coming from a repeatable upgrade path, you can build predictable growth without proportional CAC.

How to calculate it

You can compute Expansion MRR at the customer level by comparing each existing customer's MRR at the start vs. end of the period, counting only increases.

Two important implementation details:

- Define "existing customer." They must have been active (paying) at the start of the period. Otherwise, it's new or reactivation.

- Use MRR-normalized values. Annual prepay should be converted into monthly equivalents (or use CMRR (Committed Monthly Recurring Revenue) if that's how you manage commitments).

Worked example (simple)

Assume we're measuring Expansion MRR for March.

| Customer | MRR on Mar 1 | MRR on Mar 31 | Change | Counts as expansion? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 200 | 350 | +150 | Yes (+150) |

| B | 1,000 | 800 | -200 | No (this is Contraction MRR) |

| C | 500 | 500 | 0 | No |

| D | 300 | 0 | -300 | No (this is churn; see MRR Churn Rate) |

| E | 0 | 400 | +400 | No (this is new or reactivation, depending on history) |

Expansion MRR for March = $150.

Expansion rate (the ratio founders actually manage)

Raw Expansion MRR grows as you scale, so you should also track it as a percentage of starting MRR:

This makes month-to-month comparisons meaningful even as your base grows.

How it ties to NRR and net MRR churn

Expansion MRR is a major driver of NRR (Net Revenue Retention):

And it's the "good force" that can overcome churn to create Net Negative Churn dynamics.

If you want a single roll-up percentage, you'll usually look at Net MRR Churn Rate, but Expansion MRR is what tells you why net churn moved.

What drives expansion up or down

Expansion MRR is the output. The inputs are usually packaging, pricing, and customer success execution.

1) Packaging that creates a path upward

Expansion is easier when "more value" naturally maps to "pay more":

- Seat-based pricing: growth inside customers becomes revenue growth.

- Tier-based packaging: advanced features are gated, not free.

- Add-ons: buyers can expand without a disruptive migration.

If customers can get 90% of the value on your lowest tier forever, your Expansion MRR will be structurally capped—no amount of "upsell emails" fixes that.

Internal metric connections:

- Expansion tends to show up as increasing ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account) and ASP (Average Selling Price).

2) A product moment that triggers upgrades

Most expansions happen right after customers hit a threshold:

- more teammates onboarded

- more projects/workspaces created

- a compliance requirement appears

- a workflow becomes mission-critical

If you can identify that moment, you can design:

- in-product prompts

- CSM playbooks

- clear upgrade messaging

- pricing that makes the next tier an obvious step

This is where Feature Adoption Rate and Time to Value (TTV) become leading indicators of Expansion MRR.

3) Sales and CS motion design

Expansion MRR is heavily influenced by who owns it and how it's executed:

- PLG motion: expansion is driven by self-serve upgrades and seat growth.

- Sales-led motion: expansion is driven by QBRs, renewals, and account planning.

Mismatch example: if expansions require procurement and contracts, but you don't have an account management motion, Expansion MRR will be inconsistent and fragile.

4) Pricing changes and discount cleanup

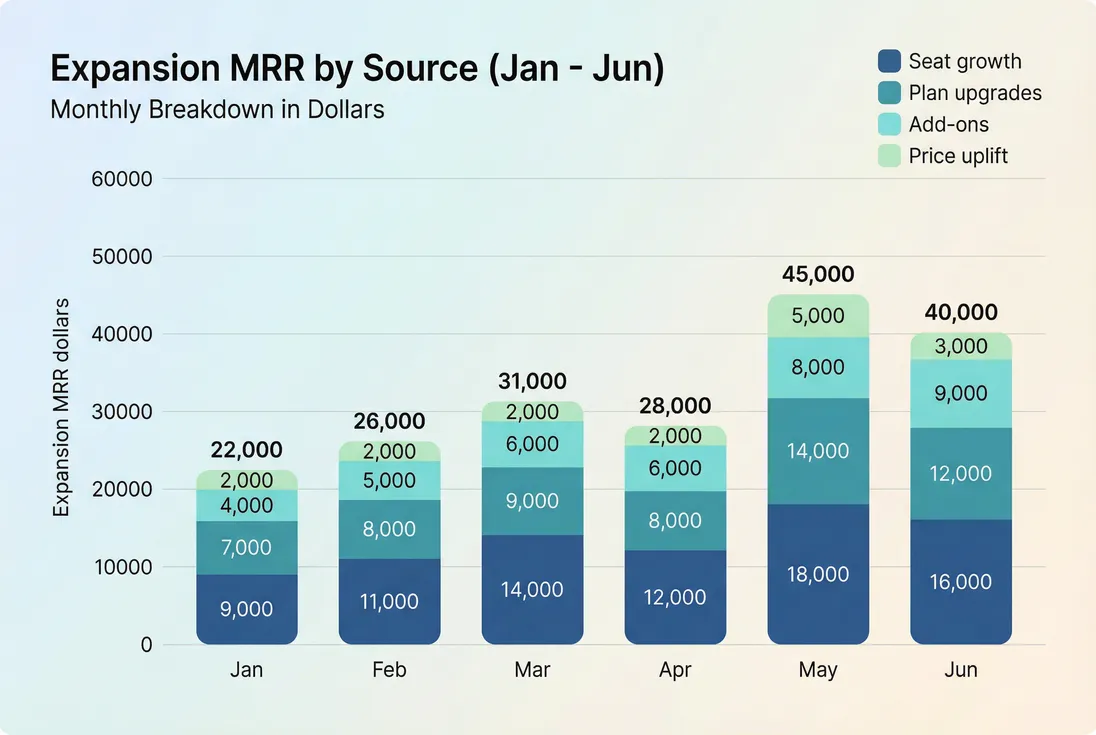

A repricing event can create a spike in Expansion MRR. That's not inherently bad—price is a lever—but founders should separate drivers:

- True expansion: customer chooses more product (seats/tier/add-on).

- Policy expansion: customer pays more for the same thing (uplift, discount roll-off).

You want both, but they forecast differently.

The Founder's perspective

I like to see Expansion MRR broken into two lines in reviews: ‘product-driven' and ‘price-driven.' Product-driven expansion tells me we're compounding value. Price-driven expansion tells me we're improving monetization. Both matter, but I will not hire CS headcount based on a one-time repricing wave.

How founders use expansion MRR

Decide where growth should come from

When Expansion MRR is strong, you can rely less on acquisition to hit targets, which affects:

- how aggressively you spend on CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost)

- your acceptable CAC Payback Period

- your capital needs and Burn Multiple

A simple planning lens:

- High expansion + low churn: invest in CS/product to scale the base.

- Low expansion + low churn: invest in packaging and activation to unlock upsells.

- High churn + high expansion: you may be "refilling a leaky bucket" with upsells—look at GRR (Gross Revenue Retention) and churn reasons.

- Low churn + low expansion: stable but capped; often a pricing/packaging ceiling.

Diagnose whether growth is broad or concentrated

Two companies can have the same Expansion MRR with different risk profiles:

- Company A: 200 customers each expand $50.

- Company B: 2 customers expand $5,000.

Company B is more volatile. This connects directly to Customer Concentration Risk and Cohort Whale Risk.

What to do in practice:

- Review expansions by customer percentile (top 10 accounts vs. rest).

- Compare expansion by segment (SMB vs mid-market vs enterprise).

- Track expansions by account age (month 1–3 vs 6–12 vs 12+).

Run better retention meetings

Retention reviews often fixate on churn. Expansion MRR forces the more useful question:

- "Which customers are getting more valuable and why?"

- "Which customers could expand but aren't?"

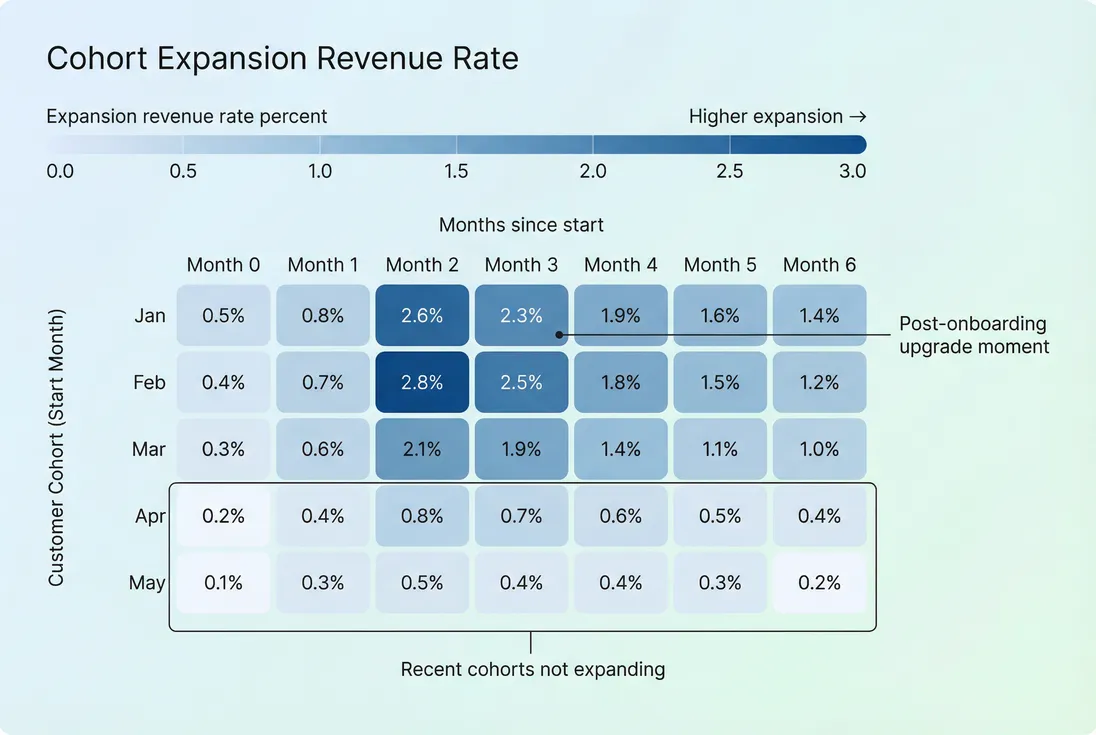

That's where Cohort Analysis becomes practical: do older cohorts expand faster? Or do they stagnate?

Breaking expansion into drivers prevents you from mistaking a one-time price uplift for repeatable product-led upgrades.

Make pricing and packaging decisions with evidence

If Expansion MRR is consistently low, founders often jump to "CS isn't upselling." More often, the issues are structural:

- Not enough differentiation between tiers

- No natural scaling unit (seats, usage, projects)

- Discounts wiping out expansion (see Discounts in SaaS)

- Annual contracts hiding movement until renewal

A practical test: pick 20 customers you believe should have expanded by now. Can you clearly articulate the next paid step for each? If not, Expansion MRR will remain weak.

Forecast more safely

Expansion is real revenue, but it's also one of the easiest places to over-forecast.

A safer approach:

- Forecast baseline expansion from cohorts that reliably expand (often 6–18 months old).

- Add campaign expansion (pricing changes, add-on launches) as separate, time-bound line items.

- Apply a haircut if expansion is concentrated in a handful of accounts.

Smoothing tip: enterprise expansions are lumpy; use T3MA (Trailing 3-Month Average) to avoid whiplash decisions.

Benchmarks and healthy ranges

Benchmarks depend heavily on segment, pricing model, and contract structure. Still, you can use these as "sanity ranges" when paired with NRR.

Expansion rate (monthly) rough ranges

| Segment / model | Typical monthly expansion rate | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| SMB self-serve (flat tiers) | 0%–1% | Often capped by packaging; expansions mainly upgrades |

| SMB PLG (seats/usage) | 1%–3% | Healthy compounding if churn is controlled |

| Mid-market | 1%–4% | Mix of seats + add-ons; some lumpy upgrades |

| Enterprise | 0%–2% monthly (lumpy) | Often shows up as quarterly step-changes |

If you want one "north star," combine it with retention:

- If GRR (Gross Revenue Retention) is weak, expansion can mask churn temporarily but won't save you.

- If GRR is strong, expansion becomes compounding growth.

How it should behave over time

In many SaaS businesses, expansion is not immediate. A common healthy pattern:

- Month 0–2: low expansion (onboarding, initial adoption)

- Month 3–9: rising expansion (team rollout, feature depth)

- Month 9+: stabilizes (unless your product scales with customer growth)

If your expansion peaks immediately after signup and then drops, you might be selling too much up front (or under-delivering after initial setup).

Cohort views show whether expansion is a repeatable lifecycle pattern or just a few isolated upgrades.

The Founder's perspective

I'm less interested in a single month's Expansion MRR and more interested in whether customers expand after they get value. If expansion only happens at renewal, I plan around renewal cycles. If it happens continuously through seats and add-ons, I can run the company with tighter cash buffers and more confidence.

Common pitfalls that distort expansion MRR

Mixing reactivation into expansion

A churned customer coming back is valuable, but it's not expansion. Keep Reactivation MRR separate so you can diagnose retention vs win-back efforts.Counting one-time revenue as expansion

Implementation fees, services, and non-recurring usage spikes will inflate expansion and cause bad hiring/forecasting.Ignoring contraction

Expansion without Contraction MRR context can be misleading. A "big expansion month" might simply be the month you finally processed downgrades and churn elsewhere.Letting FX or invoice timing create noise

If you sell internationally, currency movements can appear as expansion/contraction unless you normalize. Same with mid-month proration and invoice quirks—make sure your MRR logic is consistent.Not segmenting by plan and cohort

If expansion only exists on one plan, you might have a packaging trap. If it only exists in one acquisition channel, you might be acquiring the wrong customers elsewhere.

How to review it in GrowPanel (practically)

If you're using GrowPanel, treat Expansion MRR as something you investigate, not just admire on a dashboard:

- Start in MRR movements to isolate expansion events: /docs/reports-and-metrics/mrr-movements/

- Use filters to segment by plan, time window, or other attributes: /docs/reports-and-metrics/filters/

- Pull the customer list behind the biggest expansions and ask: is this repeatable, or concentrated?

The goal is to leave every review with one concrete decision: a packaging change, a lifecycle play, or a focused outreach list—not just a number.

Internal next reads

- NRR (Net Revenue Retention) for the full retention equation

- Net MRR Churn Rate for a single roll-up retention metric

- Contraction MRR to balance upgrades against downgrades

- Cohort Analysis to see whether expansion compounds over time

Frequently asked questions

Look at expansion as a percent of starting MRR. For many early-stage SMB SaaS businesses, 1 to 3 percent monthly expansion on the existing base is strong; 0 percent is common if packaging is flat. Enterprise is lumpier. Use a trailing 3-month average before making staffing changes.

Yes if your MRR genuinely increases from the customer due to a contract change you intended and can repeat, like a temporary intro discount expiring. But separate it in reporting so you do not confuse one-time cleanup with true value expansion. Otherwise you may overestimate product-led or sales-led upsell performance.

Expansion MRR is one input to Net Revenue Retention. NRR rises when expansion offsets churn and contraction. Net MRR churn compresses the same story into one percentage, but it can hide whether you are growing via expansions or simply not churning. Track both to diagnose the growth engine.

A pricing change can create a one-time step-up, especially if renewals reprice in batches. That can be real and desirable, but it is not the same as ongoing upsell demand. Tag expansions by driver like price uplift, seat growth, add-on adoption. Then forecast each driver separately to avoid overhiring.

Start with an MRR movement view, then filter to expansion events and sort by absolute dollars. Review the customer list behind those movements and group by plan, segment, and account age. You want to see whether expansion is broad-based or concentrated in a few whales, which changes risk and resourcing.