Table of contents

Discounts in SaaS

Discounts are one of the fastest ways to "hit the number" and one of the fastest ways to quietly weaken your business. If you're not measuring discounting with the same discipline you apply to churn, you can end up with growth that looks healthy in top-line bookings but collapses in MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue), retention, and payback.

A discount in SaaS is any reduction from your list price to the net price a customer actually pays, typically via coupons, negotiated price concessions, or term-based pricing (like annual prepay).

Are we discounting too much?

Founders usually ask this after one of three symptoms shows up:

- ARPA is drifting down even though you "didn't change pricing."

- CAC payback is getting worse despite stable acquisition costs.

- NRR is flattening because discounted cohorts don't expand.

Discounts aren't automatically bad. They're a tool for price discrimination (charging different customers different prices) and for shaping behavior (annual prepay, bigger plans, faster decisions). The problem is unmeasured discounting: you can't tell whether you're buying real demand or just giving away margin.

A practical way to frame "too much" is: discounting is too high when it fails to buy something valuable (higher win rate, shorter sales cycle, higher retention, higher expansion) relative to what it costs (lower revenue, lower margin, worse payback).

The Founder's perspective

I don't care if discounts go up in a quarter if win rate rises and churn stays flat. I care a lot if discounts go up and the only thing that improves is that deals "feel easier" to close.

What counts as a discount?

You need clean definitions before you can measure anything. In practice, SaaS discounting comes in a few repeatable forms:

Promotional discounts (usually self-serve)

- Coupon codes like "20 off"

- "First 3 months half off"

- Partner promotions

These are typically high volume and low touch. They often change the quality of signups, so you should compare discount cohorts in Cohort Analysis, not just blended averages.

Term-based pricing (annual prepay)

This is the classic "pay annually, get 2 months free" offer. It is a discount relative to the monthly list price, but it also changes cash timing and sometimes churn dynamics.

This intersects with:

- Deferred Revenue (cash collected now, recognized over time)

- Burn Rate and runway (cash in the bank changes even if ARR does not)

Negotiated concessions (sales-led)

- "We'll match your current vendor"

- "We can do 30% off if you sign by Friday"

- "We'll keep you at your old price"

This is where discount discipline matters most because it can become a habit—and it can leak into renewals.

Non-discount items founders confuse with discounts

These still matter, but track them separately:

- Refunds and credits: See Refunds in SaaS. They reduce cash and recognized revenue but aren't the same as lowering price going forward.

- One-time waivers (like setup fees): See One Time Payments. Don't mix these into recurring discount rate.

- Billing fees and payment costs: See Billing Fees. These hit margin, not price.

What is our effective price?

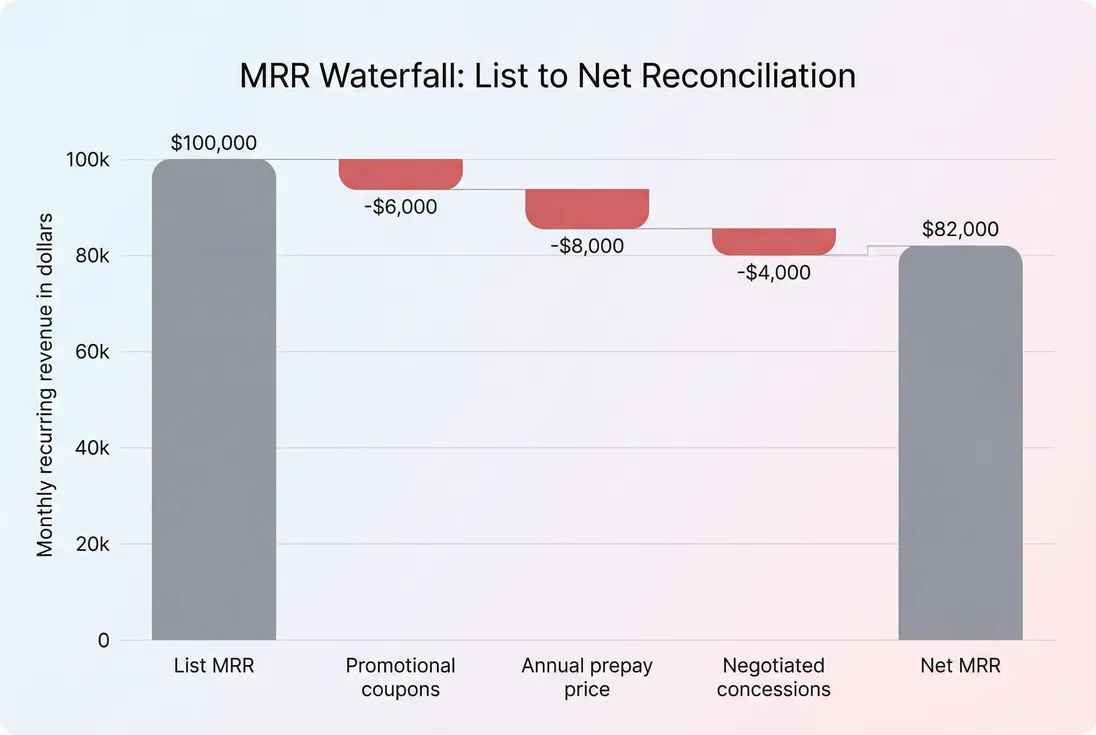

At the simplest level, discounting is the gap between list and net price.

And the net price is just:

In recurring revenue terms:

Use a revenue-weighted discount rate

A simple average (mean of account discount percentages) is misleading because a 40% discount on a $10,000/month deal matters more than a 40% discount on a $50/month plan.

A revenue-weighted version is typically more actionable:

The metric you should watch: realized price

Most founders don't actually need a standalone "discount rate dashboard" at first. You can often see discount creep by watching:

- ASP (Average Selling Price) for new sales

- ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account) overall

If ARPA is down while product usage and customer size are stable, discounting (or downsells) is usually involved.

Concrete example: annual prepay discount

- Monthly list price: $100 per month

- Annual billed price: $1,000 per year (instead of $1,200)

Effective monthly revenue is $83.33. That discount can be worth it if it reduces churn risk or improves cash efficiency—but don't pretend you're a $100 ARPA business if you're really collecting $83.

This is also where ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue) and cash can diverge from the story sales tells: your ARR should reflect the contracted recurring value, not the list price you wish you had.

Where are discounts coming from?

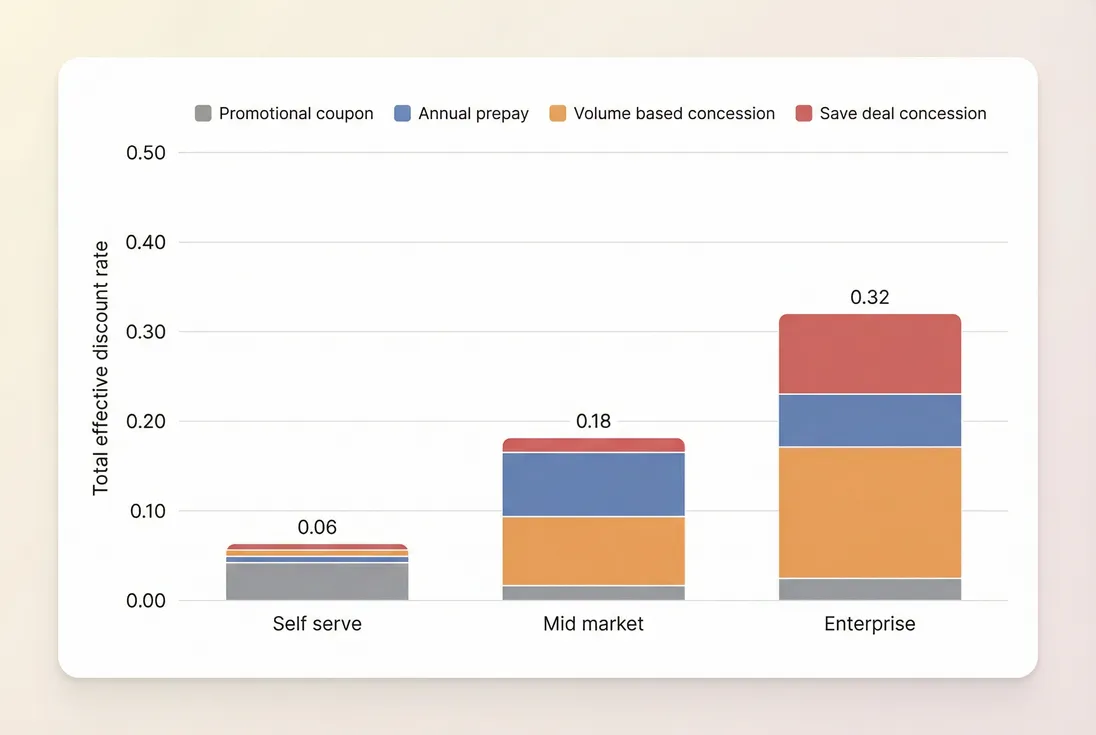

Blended discount rate hides the "why." Founders get more leverage from discount source analysis than from obsessing over the exact percentage.

Common root causes:

1) Weak packaging or unclear value

If buyers can't see why Plan B costs more than Plan A, sales fills the gap with discounts. This often shows up as:

- stable win rate

- rising discount rate

- falling ASP

2) Segment shift (this is often healthy)

Moving from SMB self-serve to mid-market can raise average discounting because negotiation becomes normal. That's not necessarily bad if:

- contract value grows faster than discount rate

- churn improves

- expansion improves

Use Customer Concentration Risk to make sure you didn't "buy" growth with a few heavily discounted whales.

3) Competitive pricing pressure

If discounts spike only when a specific competitor is present, your pricing might still be fine—but your sales team needs tighter rules on match/beat concessions, and your product positioning needs sharpening.

4) Approval process debt

If every rep can create "special pricing," you don't have pricing—you have improvisation. Discounting becomes the default close lever, even when other levers (term length, scope, implementation timing) would work.

What changes in discounts really mean

Discount rate is not a "good/bad" metric. It's a signal. Here's how to interpret common movements.

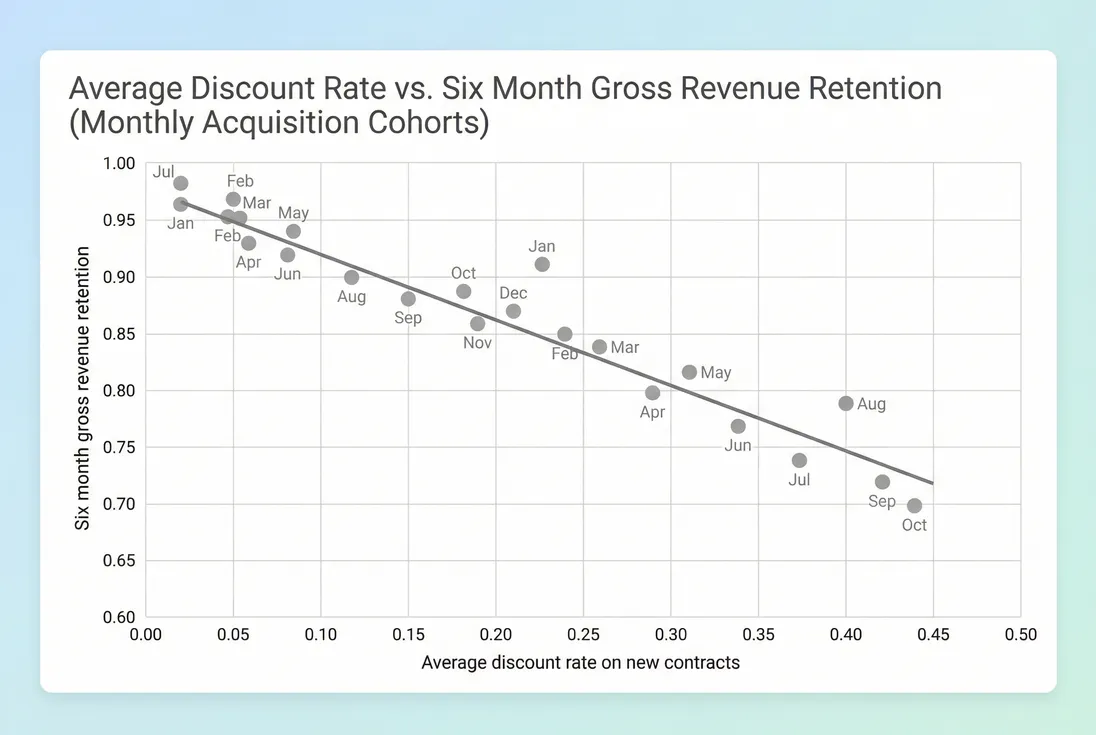

Discount rate increases, win rate increases

This can be okay—if you can show:

- higher Win Rate

- shorter Sales Cycle Length

- stable or improved retention (GRR (Gross Revenue Retention) and NRR (Net Revenue Retention))

If win rate improves but retention degrades, you likely discounted to close buyers who weren't a good fit or weren't fully convinced.

Discount rate increases, win rate flat

This is a red flag. You're giving away revenue without improving conversion. Common causes:

- reps using discounting out of habit

- discounting late in deals after the buyer has already decided

- misaligned comp (rewarding bookings, not margin/quality)

Discount rate decreases, pipeline slows

This often happens after a pricing change or a discount crackdown. Don't panic. Evaluate:

- are you losing deals that would have churned anyway?

- are you pushing the team to sell value?

- are you seeing better retention in newer cohorts?

Discounts concentrated in renewals

This is the most dangerous pattern. Renewal discounts are often "silent churn": you kept the logo but lost revenue.

Treat renewal discounting explicitly as:

- Contraction MRR if the customer stays but pays less

- a retention tactic that should be justified by saved churn risk and future expansion potential

The Founder's perspective

Renewal discounts should feel painful. If they feel routine, we're not solving the reasons customers hesitate to renew—we're just reducing the invoice until they stop complaining.

How discounts hit unit economics

Discounts touch almost every founder-level efficiency metric, usually through two pathways: lower revenue per customer and lower margin dollars.

CAC payback gets longer

If CAC stays constant but your net revenue per customer drops, payback stretches.

Connect discounting to:

A simple founder sanity check: if average discounts rose 10 points this quarter, what did that do to payback assuming churn stayed the same? If payback goes from 12 months to 15 months, you just created a financing problem.

Burn multiple can worsen even with growth

Discounting can keep top-line growth afloat while cash efficiency deteriorates, especially if you're also spending heavily to acquire those discounted customers.

Use it alongside:

- Burn Multiple

- Capital Efficiency

- Contribution Margin (if you can measure it reliably)

Gross margin dollars shrink

Even if your gross margin percentage remains stable, discounting reduces gross margin dollars because revenue is lower. This matters when you fund growth with gross margin dollars.

See Gross Margin and COGS (Cost of Goods Sold).

How founders use discount data

You're trying to make pricing and go-to-market decisions, not publish a finance report. Here are the highest-leverage ways to use discount insights.

1) Set discount guardrails by segment

A common mistake is one global rule. A more practical approach is a tiered policy that reflects how customers buy.

Here's a reasonable starting point (not a universal benchmark):

| Segment | Typical discount posture | What to optimize for |

|---|---|---|

| Self-serve | Low to none | Conversion rate, onboarding success |

| Mid-market | Moderate | Win rate without retention damage |

| Enterprise | Higher but controlled | Multi-year value, expansion path |

If you don't have clear segments, start with deal size bands (by ACV) using ACV (Annual Contract Value).

2) Require a "discount reason" taxonomy

Discount percent without reason is almost useless. You want to know whether discounting is:

- term-based (annual, multi-year)

- competitive match

- product gap / missing feature

- champion-driven urgency ("sign by Friday")

- "save" discount to prevent churn

Then you can test outcomes by reason: which reasons correlate with higher churn, lower expansion, or worse payback?

3) Compare discounted vs non-discounted cohorts

Discounts often change who you acquire. That's why cohort views matter.

Pair discount cohorting with:

- Cohort Analysis

- Retention thinking (gross vs net)

- Churn Reason Analysis for the narrative layer

4) Tie discounting to MRR movements

If you're analyzing discounting operationally, you want to see how it shows up in recurring revenue changes: new, expansion, contraction, churn.

In GrowPanel, this kind of analysis typically lives around MRR movements and slicing by filters:

The goal isn't to blame sales; it's to see whether "save" discounts are simply masking churn as contraction.

When discounting breaks the business

Discounting becomes dangerous when it creates second-order effects you don't see until later.

"Discount cliffs" at renewal

A time-bound discount that expires can create a renewal shock:

- customer feels like price "went up"

- renewal risk spikes

- your team learns to re-discount every year

If you do time-bound discounts, make them explicit, and consider committed views like CMRR (Committed Monthly Recurring Revenue) to avoid fooling yourself about forward revenue.

Hidden price increases (the opposite problem)

If you remove discounts or end grandfathering, you can create involuntary churn. Monitor:

- Voluntary Churn vs Involuntary Churn

- churn reasons and support volume

- downgrade activity

Discounting to cover onboarding or product gaps

If customers only buy when heavily discounted, that's often a signal that:

- time to value is too slow (see Time to Value (TTV))

- the product doesn't meet the promised job-to-be-done

- the ICP is wrong

Discounting is not a substitute for fixing those.

Practical guardrails that work

If you want a lightweight, founder-friendly control system:

Define list price clearly (by plan, seat, usage tier). Ambiguity makes measurement impossible.

If you're using Per-Seat Pricing or Usage-Based Pricing, define what "list" means at common usage levels.Pick one official discount metric: revenue-weighted discount rate on new business is usually the best starting KPI.

Create approval tiers (example: reps can offer up to X, managers up to Y, founders above Y). Keep tiers simple.

Track outcomes, not just inputs: discount rate by itself doesn't tell you if it worked. Track discounted cohorts' retention, expansion, and payback.

Separate discounting from cash timing: annual prepay affects cash and Deferred Revenue. Don't let "cash collected" hide "revenue conceded."

If you want a deeper treatment of recurring revenue normalization, the internal discussion in how should discounts be treated in mrr is worth aligning on with your finance and RevOps leads.

Key takeaway

Discounts are not a pricing footnote—they're a controllable lever that directly shapes your realized price, MRR quality, payback, and retention. Measure discounts in a revenue-weighted way, break them into sources, and judge them by outcomes (win rate, retention, expansion), not by whether the quarter "closed."

Frequently asked questions

Treat recurring discounts as a reduction to MRR and ARR because they permanently (or for a defined term) change what the customer is actually paying. Exclude one time credits and non recurring concessions from MRR, but still track them as a sales cost. Consistency matters more than perfection.

There is no universal benchmark because discounting depends on segment, contract length, and competition. As a rough sanity check, self serve should usually be low or near zero, mid market often sits in the low double digits, and enterprise can run higher. The key is whether discounts improve win rate without harming retention.

Discounts can inflate new customer counts while depressing revenue quality. You may show strong logo growth but weak ARPA and slower payback because each deal carries less revenue. If discounts are used to pull forward demand, you can also see higher churn later when customers reassess value at renewal.

Sometimes, but treat save discounts as a contraction with a clear hypothesis. If the customer is leaving for missing features or poor onboarding, discounting rarely fixes the root cause and can train the account to negotiate every renewal. Use a time bound concession, document the reason, and watch retention by cohort.

Look for widening gaps between ASP and ARPA, higher discount rates on similar deal sizes, and discounting that does not improve win rate or shorten sales cycle. Also watch renewal performance: cohorts acquired with heavy discounting often churn faster or expand less, reducing NRR over time.