Table of contents

CMRR (committed monthly recurring revenue)

When you're deciding whether to hire two engineers, increase paid acquisition, or commit to a 12‑month vendor contract, "last month's MRR" can be a noisy signal—especially if you bill annually, offer ramps, or close deals that start next quarter. CMRR is designed to cut through that noise by anchoring your run rate to what customers are actually committed to pay.

CMRR (Committed Monthly Recurring Revenue) is the monthly value of recurring revenue you have contractually secured, normalized to a monthly amount, based on the committed subscription terms (not the invoice timing and not one-time charges).

What CMRR reveals

CMRR answers a founder-level question: How much recurring revenue is locked in by contract, and how quickly is that locked-in base changing?

This is most valuable when your billing mechanics distort plain MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue), for example:

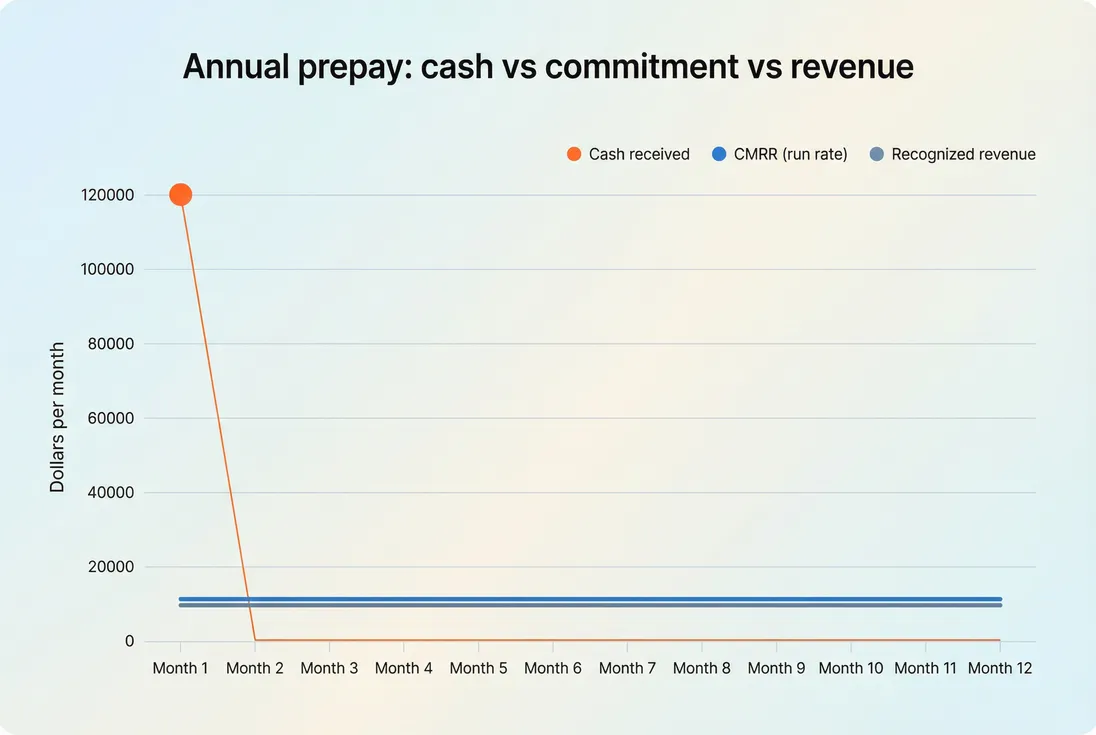

- Annual prepay: Cash arrives upfront, but the business reality is still a monthly service obligation.

- Multi-year contracts: Big bookings, but you still need a monthly run-rate view.

- Ramp deals: The contract commits to a price schedule that increases later.

- Invoiced terms: Revenue can be committed but not yet collected (important for cash planning).

CMRR is also a cleaner input into run-rate conversations like:

- "What is our revenue run rate?" (often expressed as ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue))

- "How much growth is already locked vs dependent on pipeline?"

- "How exposed are we to renewals in the next 90–180 days?"

The Founder's perspective

If you sell annual contracts and you manage the business off cash receipts, you'll over-hire in "good booking months" and panic in "light billing months." If you manage only off billed MRR, you'll underweight signed ramps and overreact to invoicing artifacts. CMRR is the middle ground: commitments, normalized.

Annual prepay creates a cash spike, but CMRR stays flat—helping you plan the business around committed run rate instead of billing timing.

How you calculate it

At its core, CMRR converts each contract's recurring commitment into a monthly amount and sums it.

For a straightforward example:

- Customer signs a 12‑month subscription for $120,000 (recurring).

- Committed months = 12

- Monthly committed amount = 120,000 / 12 = $10,000

- That customer contributes $10,000 CMRR across the committed period.

If you want the run-rate equivalent in annual terms:

Why CMRR exists alongside MRR

Most teams already track MRR because it's simple and consistent for monthly subscriptions. But as soon as you introduce:

- annual invoices,

- multi-year terms,

- ramps and scheduled increases,

- invoice-based payments,

…MRR can become "what the billing system says" rather than "what the contract commits."

A practical comparison:

| Metric | What it represents | Best for | Common pitfall |

|---|---|---|---|

| MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue) | Current recurring run rate from active subscriptions | Day-to-day growth tracking | Can be distorted by billing configuration and annual invoices (depending on your rules) |

| CMRR | Monthly recurring value committed by contract, normalized | Planning and forecasting in annual/ramped environments | Overstated if you treat non-committed usage or unsigned expansions as committed |

| Recognized Revenue | Revenue recognized under accounting rules | Financial statements | Too slow for operating decisions |

| Cash receipts | Actual cash collected | Runway and liquidity | Overreacts to prepay spikes and payment timing |

If you're running invoiced contracts, pair CMRR with cash/collection views like Deferred Revenue and operational monitoring like Accounts Receivable (AR) Aging.

What should be included

The fastest way to make CMRR useless is to let "committed" become a vibe. Define inclusion rules that match your contracts.

Include: recurring, contracted, enforceable

Generally include revenue that is:

- Recurring (subscription, license, platform fee)

- Contractually committed for a defined term (non-cancelable or with meaningful notice/penalty)

- Priced in the contract (including contracted discounts)

If you apply discounts, CMRR should reflect what the customer is actually committed to pay. If you need to reason about discount strategy, keep that analysis separate and link it back to Discounts in SaaS.

Usually exclude: one-time and non-committed variability

Typically exclude:

- Setup fees and professional services (see One Time Payments)

- True usage-based charges with no minimum commitment (see Usage-Based Pricing)

- Refunds/chargebacks as "negative CMRR" (better handled as adjustments elsewhere; see Refunds in SaaS and Chargebacks in SaaS)

Edge case: usage with a minimum If a customer has a contractual minimum platform fee plus variable usage, the minimum can be "committed," while the variable portion is not. This is where founders often split:

- CMRR floor (committed minimums)

- Usage upside (modeled separately)

Active CMRR vs booked CMRR

Founders often ask whether to count signed contracts that start later. The clean approach is to track two numbers:

- Active CMRR: contracts in effect today (best for current run-rate decisions)

- Booked CMRR: signed, future start (best for capacity and onboarding planning)

Just don't mix them in one chart without clear labeling.

The Founder's perspective

If your sales team starts pulling start dates forward (or pushing them out) to hit a quarter, active CMRR will move even if long-term value didn't change. Keeping booked CMRR separate prevents you from mistaking scheduling tactics for real demand.

What moves CMRR month to month

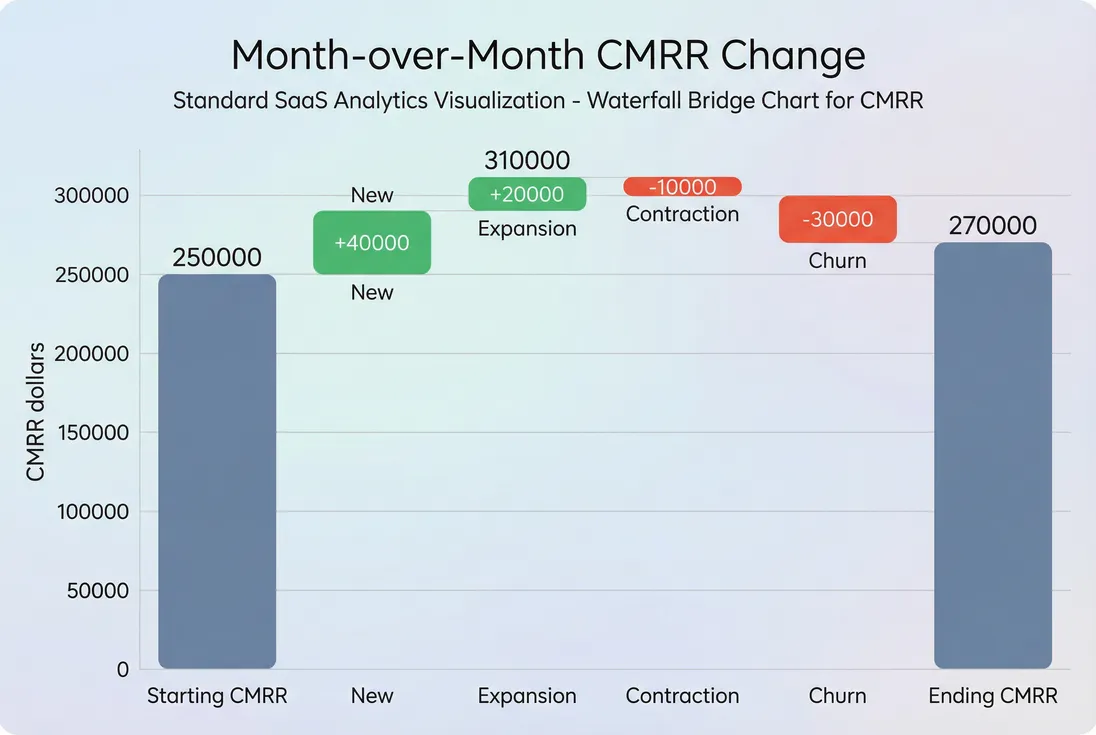

Once you trust the definition, the next question is: what changed? Treat CMRR like a bridge with consistent movement categories, similar to an MRR bridge.

Those movement types should match how you already reason about growth:

- New: new customers (see New Acquisitions)

- Expansion: upgrades, seat adds, plan increases (see Expansion MRR)

- Contraction: downgrades, seat removals (see Contraction MRR)

- Churn: cancellations and non-renewals (see MRR Churn Rate and Voluntary Churn)

When you summarize these, you can interpret performance without arguing about billing artifacts. And you can connect it to retention metrics like NRR (Net Revenue Retention) and GRR (Gross Revenue Retention).

A CMRR bridge forces clarity: growth can only come from new, expansion, and retention—not from invoice timing.

How to interpret "good" and "bad" change

CMRR going up is generally good—but why it went up matters:

- Healthy increase: New + Expansion rising while Contraction + Churn stay stable.

- Fragile increase: New spikes but churn is also rising (you're refilling a leaky bucket).

- Quality improvement: New is flat but churn declines (retention work is compounding).

- Pricing power showing up: Expansion increases after a packaging change (validate with ASP (Average Selling Price) and ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account)).

If you want a single "are we replacing what we lose?" lens, connect your CMRR movements to efficiency metrics like Burn Multiple and cash consumption like Burn Rate.

How founders use it in planning

CMRR becomes powerful when you use it to make irreversible decisions (headcount, spend, commitments) and set rules that prevent overconfidence.

1) Hiring guardrails

A simple founder rule: tie hiring pace to committed revenue, not pipeline.

Example:

- You're at $300k CMRR.

- You're considering adding $40k/month in fully loaded payroll.

- If churn is volatile, you might require that net CMRR additions cover at least 50–70% of that new fixed cost before hiring.

This is not a "perfect finance model." It's a behavioral guardrail that reduces regret.

2) Renewal exposure and concentration risk

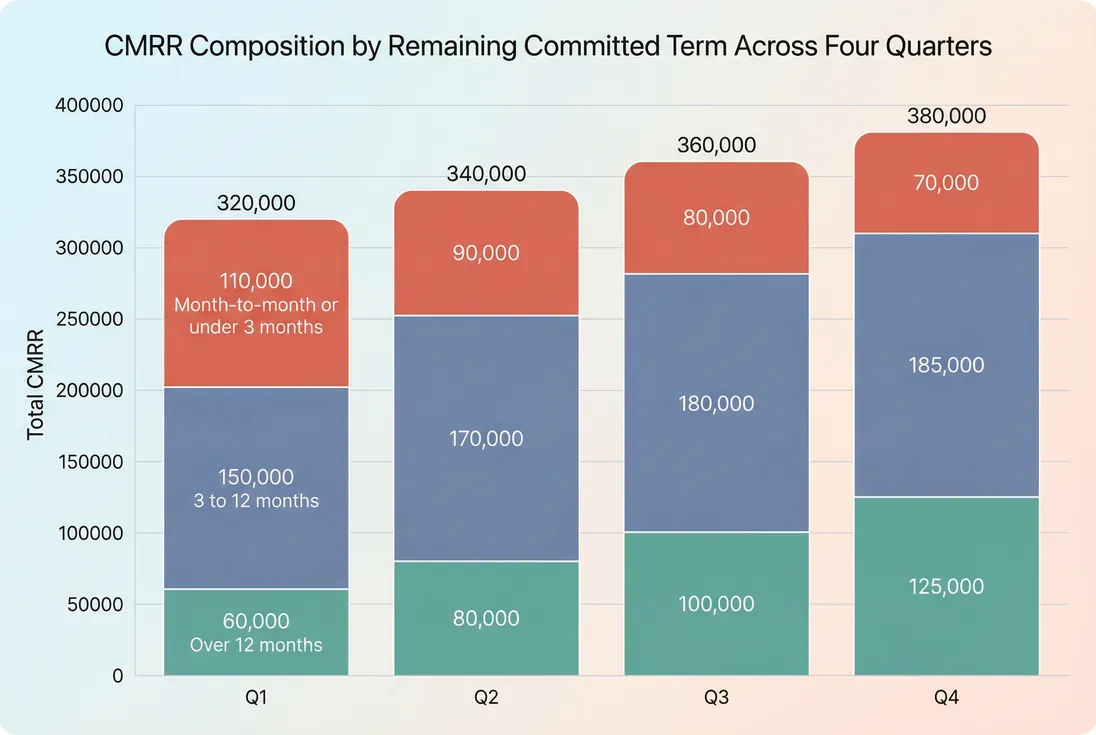

CMRR should also be sliced by remaining committed term, because not all CMRR is equally "safe."

If 40% of your CMRR is month-to-month or up for renewal within 90 days, your apparent run rate may be fragile. This pairs naturally with Customer Concentration Risk and Cohort Whale Risk.

CMRR by remaining term shows whether growth is becoming more durable (more long-term commitments) or more fragile (more near-term renewals).

3) Pricing and packaging decisions

CMRR reacts quickly to pricing and packaging changes—but only if you measure the right thing:

- If you increase prices only on new deals, CMRR lift will show up primarily in New CMRR.

- If you reprice renewals, CMRR lift should show up in Expansion at renewal (or reduced contraction).

- If you move from monthly to annual, CMRR may not change much, but cash timing will—so don't claim "growth" when it's just billing policy.

Use Per-Seat Pricing and Price Elasticity thinking to predict where CMRR might net out, and validate with actual movement categories.

4) Cohort-level retention reality checks

If net CMRR growth is slowing, founders often blame pipeline quality. Sometimes the real culprit is retention decay in earlier cohorts.

Use Cohort Analysis alongside CMRR bridges:

- Cohorts tell you where churn is coming from.

- CMRR movements tell you how much it costs you each month in committed run rate.

Where CMRR misleads

CMRR is only as good as your rules. Common failure modes:

Treating "likely" as "committed"

If an expansion is verbally agreed but not contracted, it's not committed. Keep it in pipeline, not CMRR.

Counting cancellable revenue as "committed"

Month-to-month subscriptions have weak commitment. You can still call it CMRR, but be honest: it's effectively "current run rate," not "secured revenue." That's why the term-bucket view (above) matters.

Ignoring ramp schedules

Ramps create two truths:

- Today's run rate (current CMRR)

- Already-contracted future run rate (future CMRR schedule)

If you only report the future schedule, you'll overstate current health. If you only report current, you may under-plan onboarding and support capacity.

Confusing CMRR with cash

A contract can be committed and still:

- pay late (watch Accounts Receivable (AR) Aging)

- require refunds (see Refunds in SaaS)

- create VAT complexity (see VAT handling for SaaS)

CMRR is an operating metric, not a bank balance.

Operationalizing CMRR in GrowPanel

If you use GrowPanel, keep the implementation simple and consistent:

- Use the CMRR report for your committed run-rate baseline: /docs/reports-and-metrics/cmrr/

- Review movement drivers in an MRR-style bridge so you can explain changes in one minute: /docs/reports-and-metrics/mrr-movements/

- Apply filters to isolate segments (plan, region, acquisition motion) when the headline number changes unexpectedly: /docs/reports-and-metrics/filters/

The Founder's perspective

Your board doesn't need ten revenue charts. They need one number they can trust, plus a bridge that explains change. CMRR plus movements does that—especially when you sell annual terms and the P&L lag hides what's happening in the customer base.

A practical weekly CMRR routine

For busy founders, here's a lightweight cadence that keeps CMRR actionable:

- Weekly: check net CMRR change and top drivers (new, expansion, churn).

- Biweekly: review CMRR by segment (SMB vs mid-market vs enterprise; or self-serve vs sales-led).

- Monthly: review CMRR by remaining term buckets to understand renewal risk.

- Quarterly: reconcile CMRR trends with retention metrics like NRR (Net Revenue Retention) and efficiency metrics like Burn Multiple.

If you do this consistently, CMRR becomes less of a "reporting metric" and more of a decision filter: it tells you what growth is real, what is timing, and what is at risk.

Frequently asked questions

MRR typically reflects the recurring run rate implied by what is active and billed today. CMRR focuses on what is contractually committed, normalized to a monthly amount, regardless of invoice timing. It is most useful when you sell annual or multi-year terms, ramp deals, or prepaid contracts.

Only if you clearly label it. Many teams track active CMRR (in-effect today) and booked CMRR (signed, future start). Active CMRR is better for current run-rate planning, while booked CMRR is better for capacity planning and investor updates. Mixing them creates false momentum.

There is no universal benchmark because it depends on stage, ACV, and sales cycle length. Early-stage teams often target mid-to-high single-digit monthly growth; later-stage companies may be low single digits. What matters most is consistency and whether CMRR growth outpaces your burn, measured with metrics like Burn Multiple.

Use the committed price schedule, not list price. If a discount is contractually guaranteed for a period, CMRR should reflect the discounted amount during that period. For ramp deals, prefer tracking current CMRR plus a future CMRR schedule, so you do not overstate today's run rate while still planning for expansion already under contract.

Not necessarily. CMRR is a commitment metric, not a collections metric. A customer can be committed and still pay late, especially on invoiced terms. Pair CMRR with cash-oriented views like Deferred Revenue and operational monitoring like Accounts Receivable (AR) Aging to avoid assuming contracted revenue equals available cash.