Table of contents

Technical debt

Most founders don't lose to competitors because they lack ideas. They lose because their product becomes hard to change: shipping slows, outages creep up, onboarding drags, and the "simple" enterprise request turns into a three-month rewrite. That drag is technical debt showing up as business risk.

Technical debt is the accumulated cost of earlier engineering decisions (shortcuts, quick fixes, outdated dependencies, missing tests, inconsistent architecture) that makes future changes slower, riskier, and more expensive. Like financial debt, it has principal (the work required to fix it) and interest (the ongoing penalty you pay until it's fixed).

What technical debt really reveals

Founders often treat technical debt as "code quality." In practice, it's closer to organizational throughput and reliability:

- Throughput tax: every roadmap item takes longer than it "should."

- Change risk: deployments cause regressions, rollbacks, and hotfixes.

- Constraint on strategy: you avoid certain markets (enterprise, regulated, high-scale) because the system can't safely support them.

The key is this: technical debt is not bad by default. It's a trade. Many great SaaS companies intentionally took on debt to reach product-market fit faster. The failure mode is not tracking the interest rate and letting debt compound until it forces an unplanned rewrite.

The Founder's perspective

You're not trying to eliminate technical debt. You're trying to keep it at a level where it doesn't dictate your roadmap, your uptime, or your burn. If debt starts making delivery dates unreliable, it becomes a go-to-market problem—not an engineering preference.

How to measure it in a founder-friendly way

There's no single GAAP-style "technical debt number." The practical approach is to track two inputs and two outcomes that correlate strongly with business impact.

Input metric 1: technical debt ratio (capacity share)

Define a simple ratio each sprint or month: how much engineering capacity is spent on debt work vs total capacity.

What counts as debt work hours? Use a consistent label for work that reduces future friction:

- Refactors specifically to reduce complexity

- Dependency and framework upgrades

- Test coverage and flake reduction

- Performance work that prevents future incidents

- Paying down "known bad" architecture (not new features)

What does not count? Normal feature delivery. Also avoid hiding "new feature we wanted anyway" as debt paydown—keep the label honest.

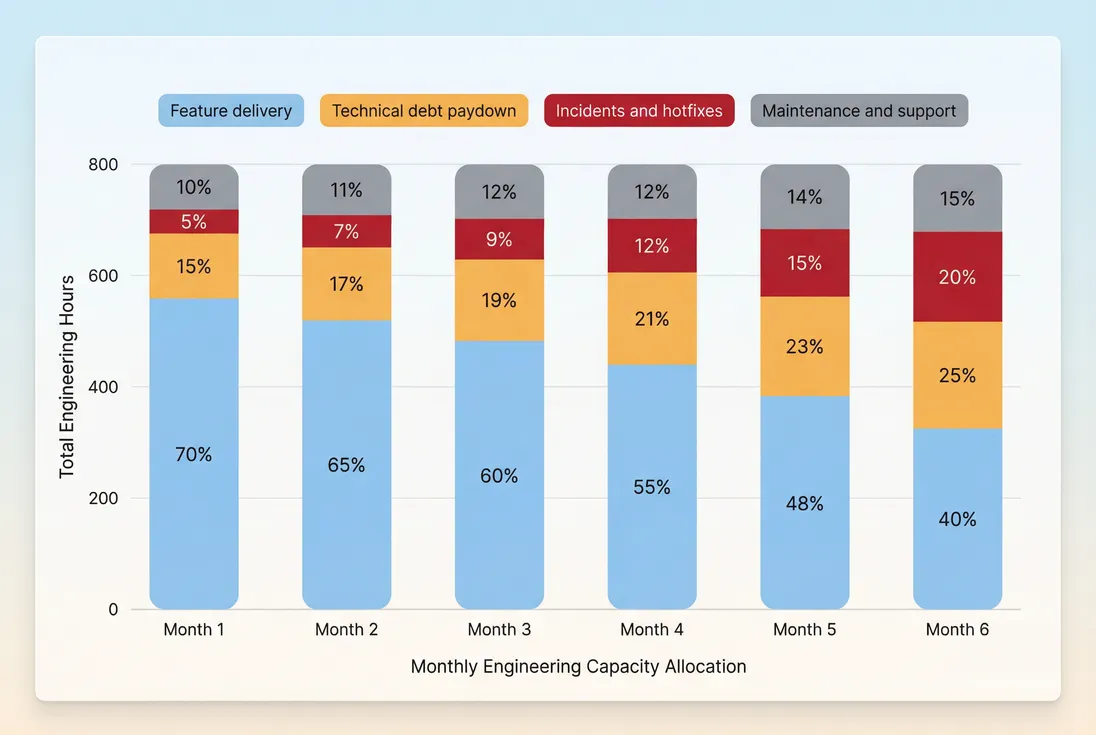

How to implement quickly: in sprint planning, tag tickets as feature, debt, maintenance, incident, and review the split monthly.

Input metric 2: debt backlog size (principal)

Track your debt principal as a small set of named debt epics with estimated effort and business impact. Don't maintain a 600-item "debt list." You want a board-level view:

- "Monolith release process modernization (4–6 weeks)"

- "Billing service test harness and rollback safety (2–3 weeks)"

- "Database migration to remove lock contention (3–4 weeks)"

A simple dollar proxy helps prioritize:

This won't be exact—and it doesn't need to be. It forces prioritization.

Outcome metric 1: delivery lead time (shipping speed)

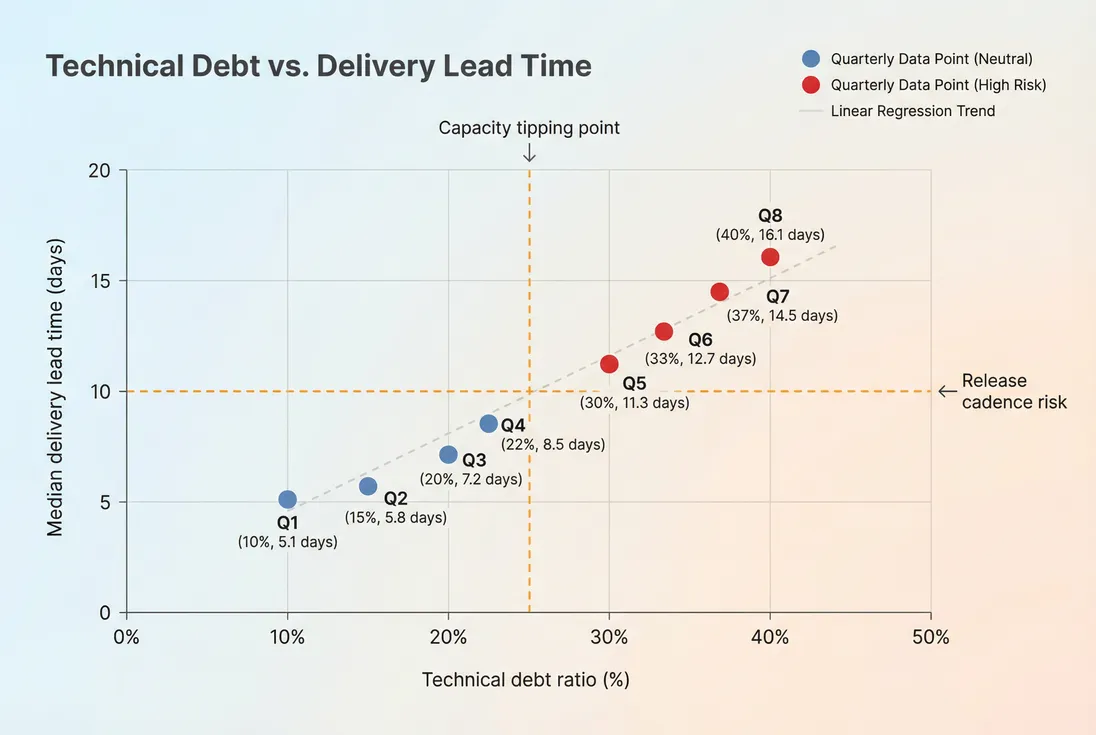

Technical debt's "interest" shows up as rising lead time for comparable changes. Pick one definition and trend it:

- "Days from first commit to production"

- "Days from ticket in progress to shipped"

If lead time rises while team size stays flat, debt is a prime suspect (alongside process issues).

Outcome metric 2: change failure rate (reliability)

Debt also increases the probability that changes break production. Track:

- Deployments that require hotfixes or rollbacks

- Repeat incidents from the same root cause category

Reliability directly ties to retention and churn—especially if you sell into teams that need trust and consistency. See Uptime and SLA for how to frame availability in customer terms.

Capacity split is the fastest leading indicator: when incidents and debt consume more of the same engineering hours, your roadmap slows even if headcount stays flat.

What changes in technical debt actually mean

The most useful interpretation is: is the interest rate rising or falling?

If the technical debt ratio rises

This can be good or bad depending on outcomes:

- Good rise: you intentionally allocate 20–30% to debt for a defined period, lead time improves, incident rate drops.

- Bad rise: debt work rises because the system is fighting you; incidents rise too; features shrink; engineers are stuck in "stabilization mode."

A common founder trap is thinking "we're investing in quality" while customers experience slower delivery and more regressions because the work isn't targeting the highest-interest debt.

If the technical debt ratio falls

Also ambiguous:

- Good fall: your architecture and tooling improved; you need less debt work; lead time stays low.

- Bad fall: you stopped paying down debt to chase features; velocity looks fine for a quarter; then lead time jumps and incidents spike.

This is similar to under-investing in retention while focusing on acquisition. The lagging indicators show up later in Retention, Churn Rate, and eventually Net MRR Churn Rate.

The Founder's perspective

Treat technical debt like retention. You can ignore it for a while and still grow—until you can't. The best time to manage it is before it becomes visible to customers.

How technical debt connects to SaaS metrics

Technical debt doesn't hit your P&L directly. It hits the systems that drive revenue.

Here's how the causal chain usually works:

- Debt increases change risk and slows shipping

- Product value arrives later (slower onboarding, slower feature delivery)

- Support load increases (bugs, edge cases, outages)

- Customer outcomes worsen

- Retention and expansion weaken

- Churn rises; growth efficiency falls

Use business metrics as "symptom detectors":

| Technical debt symptom | What you'll see | SaaS metric to watch |

|---|---|---|

| Slower onboarding, more setup issues | Prospects stall, activation drops | Time to Value (TTV) and Conversion Rate |

| Repeat outages or degraded performance | Complaints, credits, procurement blockers | Uptime and SLA and churn reasons via Churn Reason Analysis |

| Slow feature delivery | Competitive losses, longer sales cycles | Sales Cycle Length and Win Rate |

| Higher support burden | Engineering pulled into tickets | Rising burn without output: Burn Rate |

| Expansion features hard to ship safely | Upsells slip, customers don't expand | NRR (Net Revenue Retention) and Expansion MRR |

A concrete way to quantify impact is to convert "interest" into dollars:

Then compare that cost to the revenue at risk—often seen after incidents as elevated churn or lower expansion in the next 30–90 days.

If you already track revenue movement, pair incident dates with churn/expansion changes using MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue) and (if applicable) event-driven churn tracking in your internal analytics. In GrowPanel specifically, the MRR movements view can help you inspect whether churn or contraction clusters after reliability events.

When technical debt becomes dangerous

Debt becomes "dangerous" when it stops being a planned trade and becomes the default state. Watch for these thresholds.

1) Your interest rate is compounding

If you allocate more time to debt and incidents every month but shipping does not get easier, you're not paying principal—you're paying interest.

A simple heuristic:

- Debt ratio rising and

- Lead time rising and

- Incidents rising

…means the system is degrading faster than you can fix it.

As debt consumes more capacity, median lead time often rises nonlinearly—once you cross a tipping point, "small" changes start taking weeks.

2) Debt blocks revenue-critical work

A good founder definition of "high-interest debt" is: debt that prevents work tied to near-term revenue or retention.

Common examples:

- Reliability work blocking enterprise deals (SOC2 expectations, auditability, uptime guarantees)

- Data correctness issues causing billing disputes and refunds (see Refunds in SaaS and Chargebacks in SaaS)

- Architecture preventing a pricing/packaging change (see Pricing Elasticity and Per-Seat Pricing)

3) The team stops trusting the system

This one is subtle but deadly: engineers slow down because they expect regressions, tests are flaky, releases are scary, and nobody wants to touch core modules. That destroys throughput even before customers notice.

From a founder standpoint, the business risk is forecast risk: you can't confidently plan launches, marketing beats, or enterprise timelines.

How founders decide what to pay down

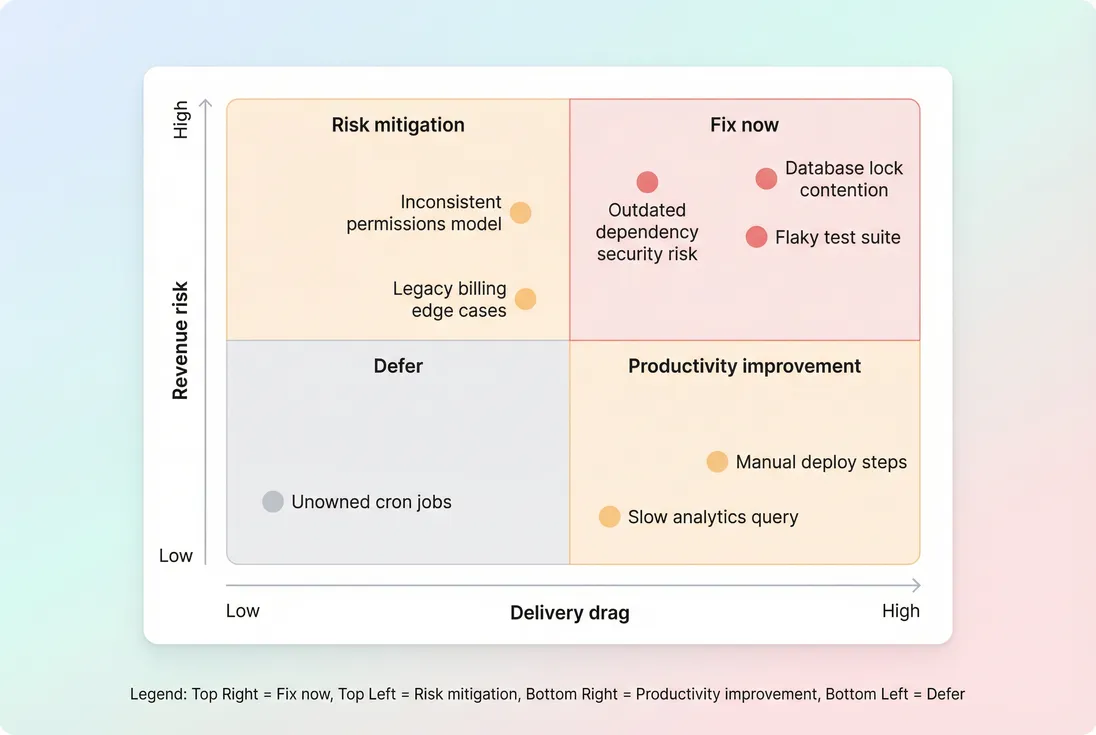

You don't want "pay down debt" to become a vague virtue. Make it a portfolio decision: spend on the debt that yields the biggest reduction in interest or risk.

Step 1: classify debt by business impact

Create a short list of debt items and score them on two axes:

- Revenue risk: could this cause churn, contraction, or blocked deals?

- Delivery drag: does this slow many teams or only a corner of the codebase?

A practical scoring rule:

- Fix first the items with high revenue risk and high delivery drag

- Defer low-risk, low-drag "cleanliness" work

Step 2: define an "exit test"

Every debt project should have a measurable "done" condition tied to outcomes, not code aesthetics:

- "Reduce median lead time from 12 days to 7 days"

- "Cut rollback rate from 15% to under 5%"

- "Remove top incident root cause category"

Step 3: set a capacity policy

Most SaaS teams do well with an explicit policy, adjusted by stage:

- Early stage: 15–25% planned debt/maintenance (expect more volatility)

- Scaling: 20–30% during major migrations, otherwise 10–20%

- Enterprise / regulated: higher baseline investment in reliability and change control

The policy matters because it prevents "debt whiplash" (ignoring it, then emergency rewrites).

The Founder's perspective

Your real job is not to pick refactors. It's to set the rules: what percent of capacity is protected for reliability, what triggers a stabilization cycle, and which customer outcomes define success.

Paying down debt without stalling growth

Founders fear the classic outcome: "we stopped features for two months and nothing improved." Avoid that with a few operating tactics.

Use "thin slice" debt paydowns

Instead of a broad rewrite, target the minimum slice that reduces interest:

- Add tests around the most-changed modules

- Replace the single worst deployment bottleneck

- Isolate one critical service behind an interface to reduce blast radius

Thin slices are easier to validate with outcome metrics (lead time, incident rate).

Pair debt work with feature work

A high-leverage pattern is: every major feature includes a small debt removal that makes the next feature cheaper.

Example: if a feature requires touching billing flows, add the tests and observability that reduce future billing regressions. That also reduces downstream costs like Billing Fees from retries, failures, or manual fixes.

Make interest visible in planning

When a roadmap item is estimated, also estimate the "debt premium":

If that premium grows quarter over quarter, it's a forcing function for prioritization. It turns "engineering feels slower" into an explicit planning input.

Don't confuse new platform work with debt reduction

A rewrite can be valid—but it's often a new product disguised as debt paydown. Before greenlighting a rewrite, ask:

- Which two outcome metrics will improve, and by how much?

- What is the migration plan and risk window?

- What revenue risk exists during the transition?

If you can't answer those in plain English, you're likely buying optionality, not reducing debt.

A simple risk-versus-drag matrix keeps debt work tied to business impact instead of taste: prioritize what blocks revenue and slows many future changes.

A simple monthly technical debt review (30 minutes)

If you want this to stay managed, run a short monthly review with engineering + product leadership:

- Trend check (5 minutes): technical debt ratio, lead time, incidents.

- Top debt list (10 minutes): review top 3 debt epics with expected outcomes.

- Customer impact (10 minutes): map recent incidents or slowdowns to churn reasons and retention signals (use Churn Reason Analysis and Cohort Analysis if you have the data discipline).

- Decision (5 minutes): adjust next month's capacity policy (for example, 15% → 25% for a stabilization push).

Tie it back to capital efficiency: unmanaged debt inflates the cost to grow. That shows up in Burn Multiple, Burn Rate, and ultimately runway.

Technical debt is only "invisible" if you choose not to measure it. Track a simple capacity ratio, pair it with lead time and reliability outcomes, and treat it as a portfolio decision tied to revenue risk. The win isn't perfect code—it's predictable shipping, fewer churn-driving failures, and a product you can keep evolving as the business grows.

Frequently asked questions

Start with a lightweight capacity split: each sprint, estimate the percent of engineering time spent on debt work like refactors, upgrades, flaky tests, and incident follow ups. Pair it with two outcome metrics you already feel: lead time to ship and incident frequency. Trend direction matters more than precision.

Early stage teams often run 20 to 40 percent debt and maintenance because the product is still settling. Mature SaaS orgs usually try to keep planned debt work around 10 to 20 percent, with spikes during major migrations. The red flag is debt rising while delivery speed and reliability fall.

Pause or run a focused debt sprint when debt interest is visible: releases routinely slip, incidents recur, or simple changes take dramatically longer than six months ago. Tie the pause to a business goal such as uptime, onboarding speed, or enterprise readiness, and define exit criteria before you start.

It usually appears first as slower Time to Value, more support load, and reliability issues. Those then surface as lower conversion, worse retention cohorts, and higher churn. Watch for changes in Uptime and SLA, churn reasons, and Net MRR Churn Rate after incidents or long shipping freezes.

Report it like a managed risk: the top two or three debt items, the customer impact, the planned capacity allocation, and the expected business outcome. Include a simple trend chart of debt ratio and delivery lead time. Investors worry less about debt existing and more about it being unmanaged.