Table of contents

Product-market fit

If you don't have product-market fit, every growth plan is fiction. You can hire sales, spend on ads, and ship features nonstop—and still end up with flat ARR because churn eats what you add. When PMF is real, the business gets simpler: forecasts stabilize, expansion starts to matter, and "growth" becomes a scaling problem instead of a survival problem.

Product-market fit (PMF) is when a clearly defined customer segment gets recurring value from your product, pays for it willingly, and keeps paying without heroic effort from your team. It's not a vibe. It's visible in retention behavior and revenue durability.

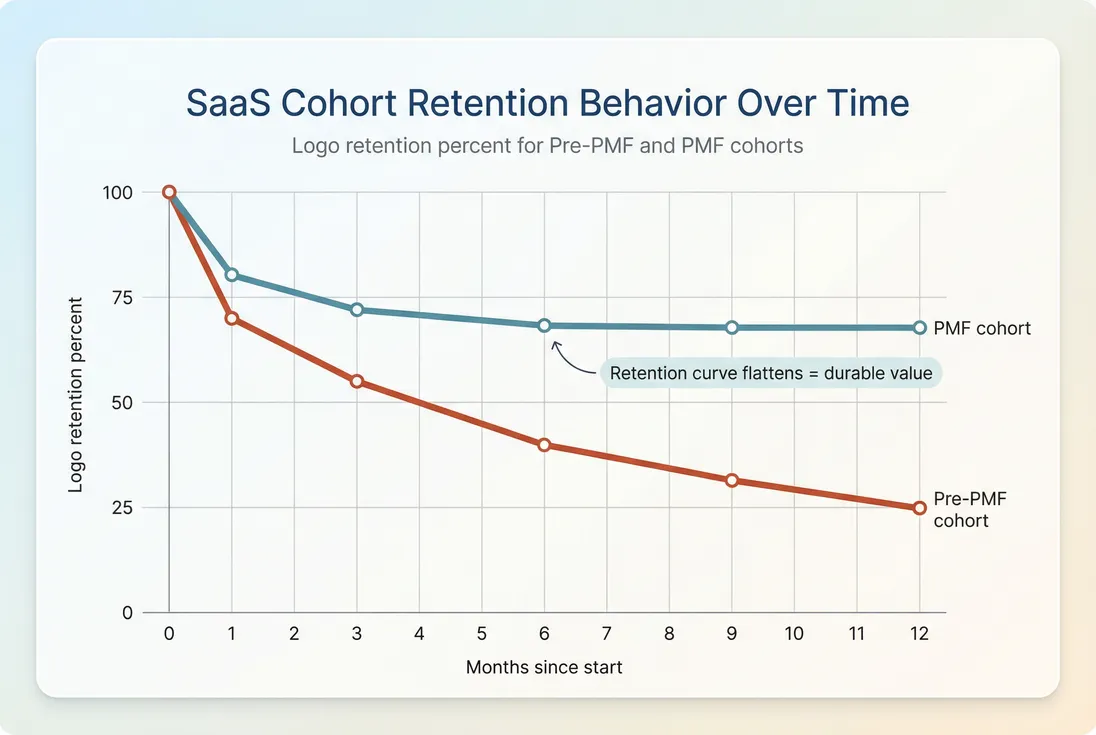

The fastest way to sanity-check PMF is whether retention drops forever or drops then flattens.

Do we have product-market fit?

You have PMF in a segment when customers stay without constant intervention and new revenue isn't mostly replacing churned revenue.

Here's the founder-grade checklist. If you can't answer "yes" to most of these, don't pretend you're ready to scale.

The three signals that matter

Cohort retention flattens

- Your retention curve drops early (normal), then stabilizes (critical).

- Use Cohort Analysis to look at retention by start month and by segment (plan, channel, use case, contract type).

Churn stops dominating your narrative

- You still have churn, but it's explainable and bounded.

- Watch Logo Churn for "do they leave?" and MRR Churn Rate for "how much revenue leaves?"

Expansion starts showing up naturally

- Existing customers increase spend because they get more value, not because you nag them.

- This is why founders care so much about net churn dynamics.

A useful summary metric for the "revenue durability" side is net MRR churn:

- When this moves down, your product is compounding.

- When it's near zero, you can grow without constantly refilling the bucket.

- When it's negative, expansion outpaces losses (rare early, powerful when real).

If you want the full breakdown, read Net MRR Churn Rate.

The founder's perspective

PMF is not "customers like it." PMF is "customers don't leave, and some pay more over time." That changes what you can afford: more CAC, more hiring, longer payback, and bigger bets.

What "PMF" is not

Founders regularly confuse these for PMF:

- High top-of-funnel (signups, demos, inbound). Attention is not retention.

- A few big logos. This can be real, but it can also be a services-driven mirage.

- Great NPS with weak retention. People can like you and still churn.

- Growth driven by discounts. You bought volume, not fit. See Discounts in SaaS.

PMF is segment-specific. You can have PMF in one ICP slice and be totally broken in another. That's normal. The mistake is scaling into the broken slice because the pipeline "looks bigger."

What numbers actually prove it?

You don't need a single magic PMF score. You need a small set of numbers that answer one question:

Is value being delivered repeatedly enough that revenue sticks?

Start with retention and cohorts

Your most practical PMF dashboard is:

- Logo retention (by cohort)

- Revenue retention (by cohort)

- Net churn trend over time

- ARPA trend by segment

Why ARPA? Because PMF isn't only "they stay." It's also "they pay enough to support the business." See ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account).

Benchmarks (use with caution)

PMF "benchmarks" are slippery because pricing, contract length, and customer maturity change everything. Still, you need a gut-check.

| Motion | Early PMF hint | Strong PMF hint | What it means operationally |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMB self-serve | 3-month logo retention stabilizes | 6–12 month retention plateau | You can invest in onboarding + lifecycle messaging |

| Mid-market | Gross retention improves steadily | Expansion becomes repeatable | You can build CS motions and upsell packaging |

| Enterprise | Renewals become boring | Multi-year expansions happen | You can scale sales headcount with confidence |

Use this table as a smoke test, not a goal. The real question is whether your retention curve flattens and stays flat across multiple cohorts.

Use MRR movements to see reality

If you're not looking at revenue changes as components, you'll lie to yourself. A single ARR number hides the fight between new sales, churn, contractions, and expansion.

PMF shows up in the composition of growth: churn becomes manageable and expansion starts doing real work.

If you use GrowPanel, this is exactly why MRR movements and filters matter: you want to isolate the segment that retains, then see if expansion is coming from the same segment (not from a totally different customer type). (See: MRR and Filters.)

The founder's perspective

If your growth depends on constantly adding New MRR to cover churn, your "strategy" is just fundraising with extra steps.

Don't let contract terms fool you

Annual contracts can mask weak PMF for months. You'll think you're fine until renewals hit. If you sell annual, watch:

- Renewal behavior by cohort (not just "booked ARR")

- Contraction at renewal (they renew but downgrade)

- Time-to-value (if it's slow, renewal risk is high)

CMRR can help you stay honest about committed revenue versus what you hope renews. See CMRR (Committed Monthly Recurring Revenue).

Where founders get fooled

PMF confusion usually comes from mixing segments and averaging away the truth.

Trap 1: One cohort saves the average

A single strong cohort can hide five weak ones. You feel momentum. The business is quietly accumulating future churn.

What to do:

- Split cohorts by pricing plan, acquisition channel, and use case.

- Compare retention curves side by side.

- Treat the best-retained slice as your real ICP until proven otherwise.

If you're using GrowPanel, this is where cohorts plus filters plus customer list become a weapon: find the customers who stick, then inspect what they have in common. (See Cohorts.)

Trap 2: Whale-driven false confidence

A few large customers can make your ARR look healthy while the rest churns. The risk isn't just revenue concentration—it's product direction. You'll build for edge-case enterprise needs and lose the core.

If you have whales, isolate them:

- Look at retention and churn with and without the top accounts.

- Track whether expansion is broad-based or whale-only.

If this is a real concern, read Customer Concentration Risk and Cohort Whale Risk.

Trap 3: Support and services hiding product gaps

If retention is "good" only because:

- founders are on every onboarding call

- your team is doing manual workarounds

- you're effectively delivering a service

…you don't have PMF yet. You have a consulting business attached to a product.

The test is simple: Can a new customer get value without heroics? If not, scaling will break you.

Trap 4: Discounting your way into churn

Discounts can be fine. But if your close rate depends on heavy discounting, you're often pulling in customers with weaker pain and lower willingness to change.

Discounts tend to show up later as:

- higher logo churn

- higher contractions at renewal

- lower expansion

If you discount, do it intentionally and track the downstream cohort outcomes. Otherwise you're manufacturing future churn.

What actually moves product-market fit

PMF improves when you reduce "value friction" and increase "value density." That's it.

Here are the levers that actually change retention and expansion.

Narrow your ICP until retention improves

The fastest PMF progress usually comes from saying "no" more often.

What to do next:

- Identify the cohort with the best retention.

- Write down what is true about them (industry, team size, job to be done, urgency, constraints).

- Update messaging and qualification to aim directly at that profile.

This is not a branding exercise. It's churn prevention.

The founder's perspective

A narrower ICP feels like shrinking the market. In reality, it increases the percentage of customers who succeed, which increases the only market size that matters: the one that pays you for years.

Fix time-to-value before you add features

If customers don't reach the "aha" moment fast enough, retention dies early and you'll misread PMF as a top-of-funnel problem.

Typical fixes that move the needle:

- Shorten setup steps.

- Default to a successful configuration.

- Remove optionality early (advanced settings can wait).

- Build a guided path to the first successful outcome.

This is also where Onboarding Completion Rate and Time to Value (TTV) are useful concepts—even if they're not financial metrics.

Charge in a way that matches value

Pricing doesn't create PMF, but it can reveal it or hide it.

- If you price too low, you attract low-intent customers and inflate churn.

- If you price too high for the value delivered early, you choke adoption and blame marketing.

Practical approach:

- Use ARPA to understand what your retained customers willingly pay. See ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account).

- If your best cohorts retain and expand, you may have room to raise prices for that segment.

- Don't reprice the whole business based on your worst segment. Fix the segment, or stop targeting it.

If you're experimenting with packaging, read ASP (Average Selling Price) and Per-Seat Pricing for common tradeoffs.

Make expansion a product behavior, not a sales event

Expansion that requires a hero salesperson isn't repeatable early. The cleanest PMF signal is when customers "grow into" higher spend because usage, seats, or scope naturally increases.

To encourage that:

- Align plan limits with real value thresholds.

- Put the upgrade moment right next to the value moment.

- Avoid arbitrary gating that creates resentment and churn.

Expansion should feel like progress, not punishment.

Improve reliability and remove churn triggers

Some churn is "no fit." A lot is "product pain."

Foundational churn triggers:

- broken workflows

- poor performance

- missing integrations

- confusing billing

A boring product is often a retaining product. If uptime and trust are shaky, PMF will never stabilize. See Uptime and SLA.

When to scale (and when not)

Scaling is not "we want to grow." Scaling is "we can predictably turn inputs into durable ARR."

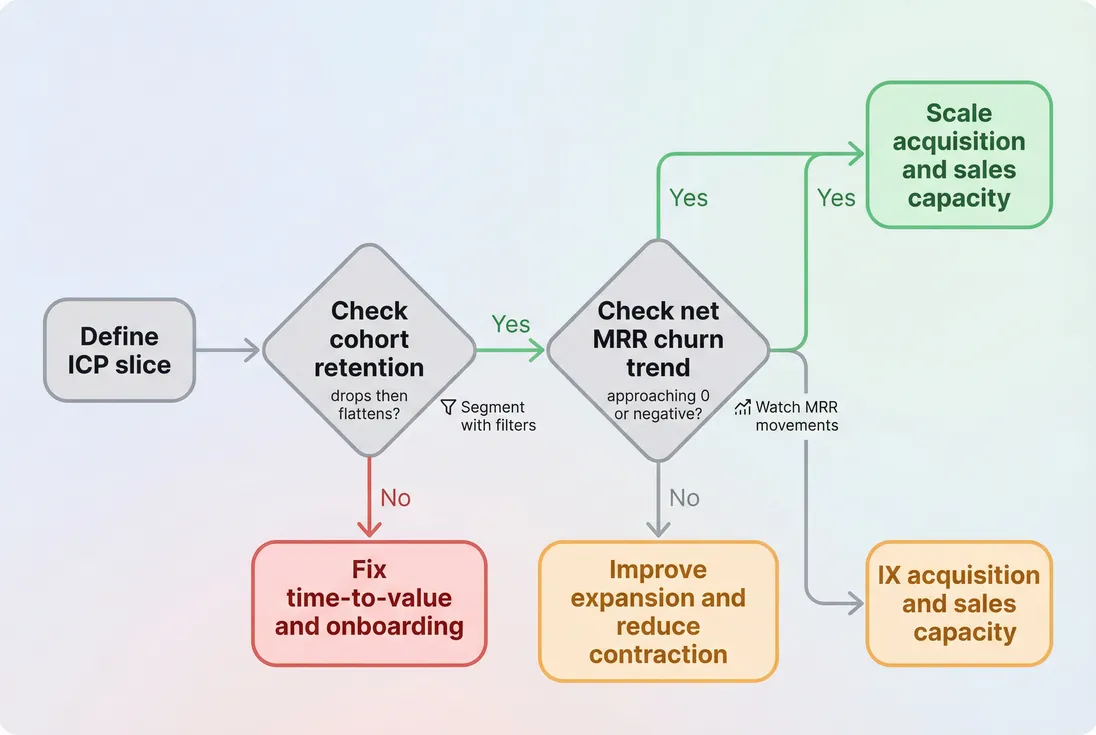

Here's a clean decision framework founders can actually use.

Scale only after retention stabilizes and net churn stops being your main growth constraint.

Green lights to scale

Scale harder when these are true in your core segment:

- Retention curves flatten across multiple recent cohorts

- Logo churn is stable or improving

- Net MRR churn is trending toward zero (or better)

- ARPA is stable or rising without rising churn

At that point, your spend is buying durable ARR, not temporary revenue.

This is where unit economics start to matter more. If you're increasing spend, you should understand CAC Payback Period and Burn Multiple so you don't scale yourself into a cash crisis.

Red lights (stop scaling, start fixing)

Stop pouring fuel on the fire if:

- Retention keeps sliding with each cohort

- Growth is mostly New MRR replacing churn

- You need heavy discounting to close

- Your best customers are happy but rare (weak repeatability)

What to do instead:

- Narrow ICP.

- Fix time-to-value.

- Reduce churn triggers.

- Improve packaging to align with value.

What to ignore (even if investors ask)

Ignore these as primary PMF proof:

- "We're growing 20% MoM" (without retention context)

- "Our NPS is high" (without churn context)

- "We have a big TAM" (TAM doesn't retain customers)

- "Our pipeline is up" (pipeline doesn't equal durable revenue)

PMF is not a slide. It's behavior that repeats.

A practical PMF operating cadence

If you want PMF to become real (or get stronger), run this cadence for 8–12 weeks:

Weekly: retention reality check

- Review logo retention and churn drivers for the most recent cohorts.

- Pull 5 churned customers and classify the real reason (no fit vs product pain).

Weekly: MRR composition review

- Look at new, expansion, contraction, churned.

- If churn is up, don't celebrate bookings.

Biweekly: ICP tightening

- Update qualification rules based on who retained.

- Remove one "bad-fit" segment from targeting.

Monthly: pricing and packaging sanity

- Compare ARPA and retention by plan.

- If a plan has weak retention, fix packaging or stop selling it.

Monthly: cohort deep dive

- Pick one cohort and trace the customer journey.

- Find the earliest divergence between retained vs churned accounts.

The founder's perspective

The goal isn't to "find PMF" once. The goal is to keep shifting your mix toward customers who retain and expand, then build the company around that reality.

Next steps (if you want to act today)

- If you're unsure you have PMF, start with cohort retention curves and segment them. Read Cohort Analysis.

- If you're retaining but not compounding, focus on net churn dynamics. Read Net MRR Churn Rate.

- If you're growing but cash feels tight, you're likely scaling before PMF. Read Burn Rate and Burn Multiple.

Frequently asked questions

Hype shows up as signups, demos, and a few loud customers. Product-market fit shows up in cohorts: customers stick around, usage stabilizes, and churn stops being your dominant growth constraint. If retention is weak, you do not have PMF. If retention is strong, you can buy growth.

Use your own segment first, not a generic benchmark. But as a reality check: if your logo retention keeps falling month after month, PMF is not there. You're looking for a curve that drops early, then flattens. Once it flattens, expansion becomes the next test.

No. That is paid growth masking a leaky product. Fast growth with high churn is a treadmill: CAC rises, support load rises, and you keep rebuilding pipeline to stand still. PMF is when growth becomes easier because customers stay and your net churn stops fighting you every month.

If you cannot retain, pricing is not the core problem. Fix value delivery first. But you also should not underprice while chasing PMF; it attracts the wrong customers and inflates churn. Run pricing tests on your best-retained segment. If retention holds, you just found stronger PMF and better unit economics.

Confusing a handful of whale customers for PMF. A few big accounts can hide weak retention and create false confidence. Segment your cohorts by plan, use case, or acquisition channel. If only one slice retains, your PMF is narrow. That is fine, but you must build the company around that slice.