Table of contents

Price elasticity

Founders rarely lose a SaaS business because the product "isn't good enough." More often, they underprice for years (leaving growth capital on the table) or raise prices blindly (triggering a conversion drop or churn spike they can't reverse quickly). Price elasticity is the metric that tells you which risk you're actually taking.

Price elasticity measures how sensitive demand is to a change in price. In plain terms: when you change price by X percent, how much does quantity demanded change by Y percent?

What price elasticity reveals

Elasticity is a fast read on your pricing power—but only when you define "demand" correctly for your business.

In SaaS, demand can mean different "quantities," depending on the pricing model and decision:

- New business demand: paid conversions, closed-won deals, new customers

- Expansion demand: seats purchased, upgrades, add-ons, higher-tier adoption

- Retention demand: renewals, downgrades, churn (customers "demanding" continued subscription at the new price)

The core insight is this:

- If customers are inelastic, you can raise price with relatively small demand loss.

- If customers are elastic, price increases cause demand to drop sharply, and revenue may fall unless something else offsets it (better targeting, stronger value, improved packaging).

The Founder's perspective

If you're planning a price increase, elasticity is less about "What will happen to signups next week?" and more about "Will this change improve MRR and margin over the next two quarters without increasing churn?" Pair elasticity with MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue) and retention metrics before you commit.

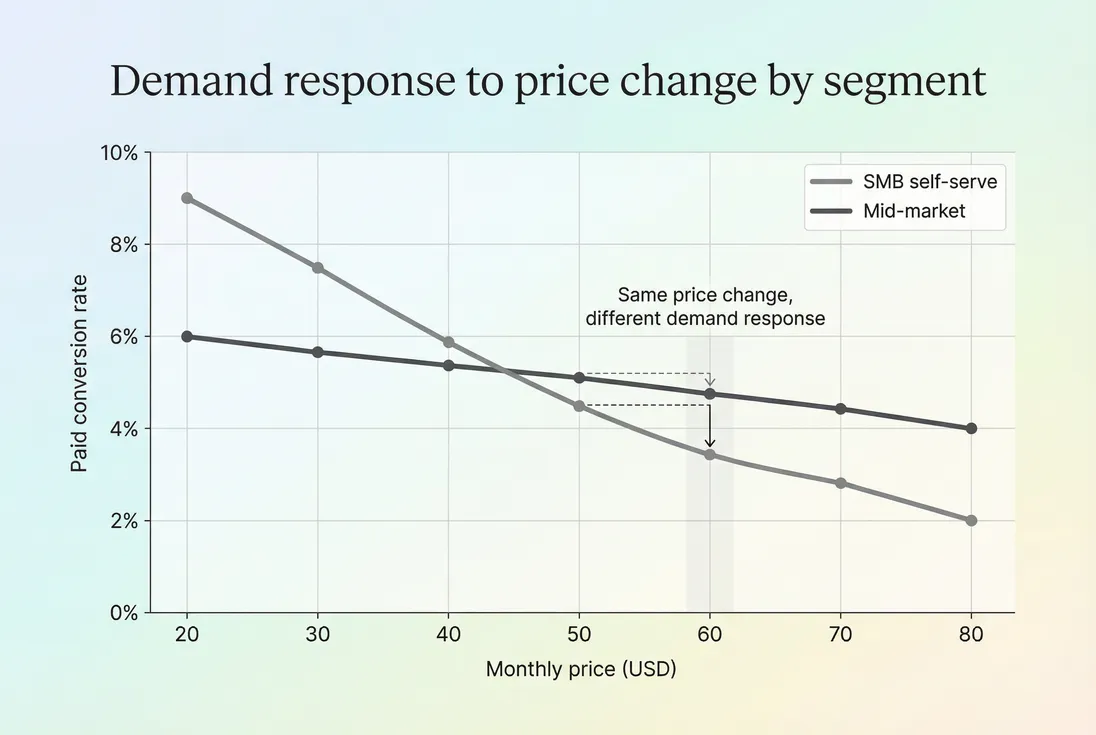

Elasticity is the slope of your demand response: a small price move can cause a small or large conversion change depending on segment.

How do you calculate it?

The standard definition is:

To compute percent changes:

A few practical notes for SaaS:

- Elasticity is usually negative. Price goes up, quantity goes down. Many teams talk about the absolute value (how sensitive) and ignore the sign. Be explicit in your analysis.

- Define quantity before you compute anything. If you change seat pricing, quantity might be seats per account, not number of accounts.

- Pick a time window that matches the buying motion. For sales-led, measuring "quantity" over 7 days will undercount deals that are still in-cycle.

A quick numeric example

You raise your monthly price from $50 to $60:

- Price change: +20%

- Paid conversions per week: from 100 to 92 (−8%)

Interpretation: demand is fairly inelastic in this window. You lost some conversions, but not many relative to the price increase.

Translating elasticity into revenue impact

For small changes, you can approximate the percent revenue change as:

If elasticity is −0.4 and price increases by 20%:

- Revenue change ≈ (1 − 0.4) × 20% = +12%

That's directionally useful. In SaaS, though, you still need to verify the second-order effects (churn, downgrades, expansion), which can dominate the long-run outcome.

The Founder's perspective

When your team says, "Elasticity is −0.4, we're good," the correct follow-up is: "For which segment, on which funnel step, and what happened to retention?" A price test that improves checkout revenue but worsens renewal behavior can destroy LTV (Customer Lifetime Value).

Will a price increase grow MRR?

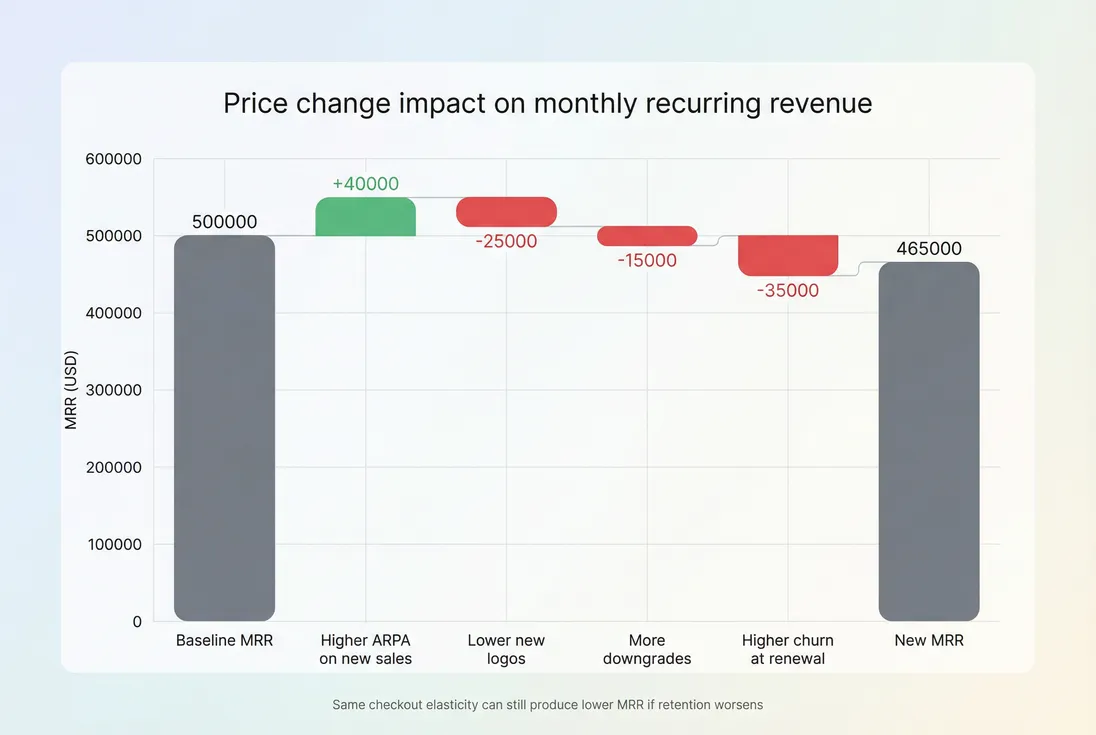

Founders care about elasticity because the goal isn't "maximize conversion." It's maximize durable MRR and cash flow.

A price increase hits multiple MRR components at once:

- New MRR may fall (fewer new customers)

- Expansion MRR may fall (less willingness to upgrade, fewer seats)

- Contraction MRR may rise (downgrades)

- Churn may rise (customers exit rather than renew)

This is why you should translate any "demand" elasticity into an MRR movement view and watch retention by cohort.

If you're instrumented well, you'll evaluate the change using:

- ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account) (did it rise as intended?)

- ASP (Average Selling Price) (especially if packaging changed)

- Logo Churn and Net MRR Churn Rate (did churn or downgrades worsen?)

- Cohort Analysis (did newer cohorts behave differently than older ones?)

In SaaS, the long-run outcome of a price change depends on churn, downgrades, and expansion—not just top-of-funnel conversion.

A practical decision table

Use this to interpret elasticity quickly for a single quantity metric (like paid conversions), then validate against retention.

| Elasticity (absolute) | What it usually means | Pricing implication | What to check next |

|---|---|---|---|

| < 0.5 | Strong pricing power | You can likely raise price | Renewal cohorts and downgrades |

| 0.5 to 1.0 | Mixed sensitivity | Raise with packaging/value improvements | Segment-level results by ICP/channel |

| > 1.0 | Highly price-sensitive | Price increases likely reduce revenue | Consider lower entry plan, annual incentives, differentiation |

| Unstable over time | Noisy or confounded | Don't trust one snapshot | Improve experiment design and segmentation |

No table replaces real measurement, but it helps you avoid the common mistake: treating a single aggregate elasticity number as "truth."

Which customers are more elastic?

In SaaS, elasticity is rarely a single number. It varies by segment, use case, and buying context.

The biggest drivers

Strength of differentiation

- If you are clearly better or uniquely trusted, demand is less elastic.

- If alternatives are close substitutes, elasticity rises quickly.

Switching costs and workflow lock-in

- Products embedded in daily workflows (data pipelines, finance close, security) tend to be less elastic.

- "Nice-to-have" tools or tools used weekly tend to be more elastic.

Buyer type and budget owner

- A founder paying on a credit card behaves differently than a department renewing a budget line item.

- Enterprise renewals may look inelastic, but procurement can introduce "step function" discount demands.

Pricing model

- Per-Seat Pricing often creates elasticity through seat compression (customers reduce seats to manage cost).

- Usage-Based Pricing can lower perceived elasticity if customers feel they pay for value, but it can also introduce sharp thresholds (customers optimize usage to avoid the next tier).

Discounting and sales behavior

- If some customers get heavy discounts and others don't, your "price" isn't one number.

- Read Discounts in SaaS to avoid mixing list price with realized price when you measure elasticity.

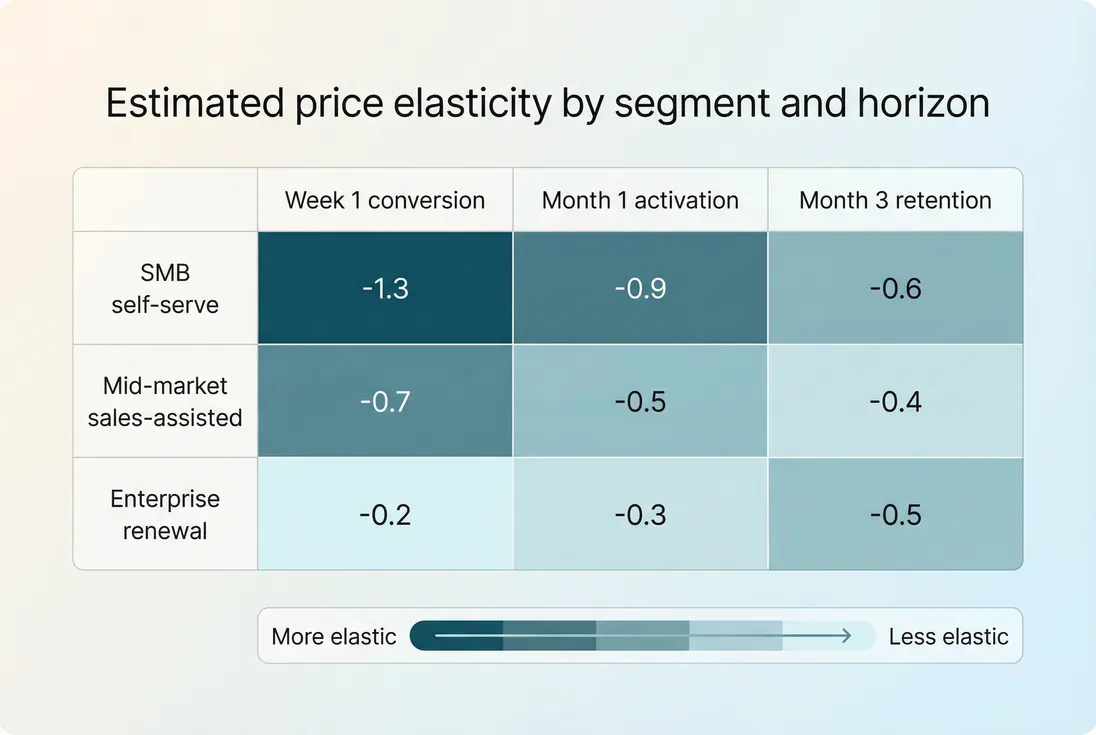

Segment elasticity, not global elasticity

A founder-grade approach is to build elasticity estimates for a few segments that matter operationally:

- ICP vs non-ICP

- Self-serve vs sales-assisted

- Monthly vs annual

- By acquisition channel (paid search is often more elastic than referrals)

- By plan / tier

If you're using GrowPanel, this is where filters and cohort breakdowns matter: you want to isolate the segment that actually changed and avoid averaging away the signal. See /docs/reports-and-metrics/filters/ and /docs/reports-and-metrics/cohorts/.

Elasticity often changes with time horizon: the same price move can look very elastic at checkout but less elastic after activation—or the reverse at renewal.

How founders use elasticity in real decisions

Elasticity becomes useful when it informs a specific decision and a specific tradeoff.

1) Setting your next price move size

Instead of debating "10% or 30%?", use elasticity to bracket outcomes.

If you estimate elasticity at −0.5 for your primary self-serve ICP:

- +10% price → about −5% quantity (directionally)

- +25% price → about −12.5% quantity (directionally)

Then translate into MRR impact using your baseline ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account) and your observed conversion volume. This doesn't need to be perfect; it needs to be good enough to avoid "random pricing."

2) Choosing packaging vs pure price

If elasticity is high (very sensitive), you often get better results by changing packaging instead of pushing the same plan up-market:

- Introduce a higher tier with stronger value boundaries

- Move a costly feature to a higher plan

- Add usage limits and charge for overages (with care)

Packaging changes can reduce apparent elasticity by letting customers self-select rather than churn.

3) Deciding where to invest in differentiation

If a segment is highly elastic, you can respond in two ways:

- Compete on price (risky in SaaS)

- Reduce elasticity by improving perceived value and switching costs

The metric helps you decide where product and positioning work has the highest financial leverage.

The Founder's perspective

Elasticity is a map of where your value proposition is fragile. If SMB is at −1.3 but mid-market is at −0.5, that's not just a pricing insight—it's a go-to-market insight. You may be under-investing in sales-assist, onboarding, or a mid-market feature set that creates willingness to pay.

4) Forecasting changes to retention economics

The pricing move that "wins" on new bookings can still lose on lifetime value if it increases churn.

After a price change, monitor:

- Cohort Analysis on logo retention and revenue retention

- Net MRR Churn Rate to see whether downgrades and churn offset higher ARPA

- MRR movement breakdowns to attribute what actually changed (see /docs/reports-and-metrics/mrr-movements/)

If you see worse retention in new cohorts only, that often indicates selection effects (you attracted different customers at the old price than at the new price).

When elasticity "breaks" (common traps)

Elasticity is easy to misuse. These are the failure modes I see most often in SaaS.

Mixing list price with realized price

If you discount unevenly, you don't have one price. Your measured "elasticity" might actually be "discount policy variance."

Fix: measure realized price and segment by discount band. Use ASP (Average Selling Price) as your sanity check.

Confounding from channel mix or lead quality

If you raise price at the same time you change spend, messaging, or targeting, your quantity change may not be due to price.

Fix: hold acquisition inputs stable during the test, or segment by channel and compare like-for-like.

Ignoring the sales cycle

In sales-led motions, a price change can affect:

- Win rate

- Discounting behavior

- Deal cycle length

- Plan mix

You might not see the full effect for 30 to 90 days.

Fix: measure elasticity at multiple points (proposal acceptance, close, activation), and don't overreact after one week.

Looking only at the mean

Averages hide cliffs. Many SaaS products have threshold behavior:

- Under $49 feels "self-serve"

- Over $99 triggers manager approval

- Over $499 triggers procurement

Elasticity around thresholds is not smooth; it can jump.

Fix: test around known psychological or budget thresholds and monitor funnel step drop-offs.

Using short-term elasticity to justify a long-term decision

The most expensive mistake is using a checkout elasticity estimate to justify a permanent pricing change without validating retention.

Fix: always pair pricing analysis with retention and churn metrics like Logo Churn and Net MRR Churn Rate.

A practical workflow to measure elasticity

You don't need a PhD experiment. You need a clean comparison.

Step 1: Choose the decision and the unit

Pick one:

- "Should we raise self-serve monthly price?"

- Quantity: paid conversions per visitor (or per trial start)

- "Should we increase per-seat pricing?"

- Quantity: seats per customer

- "Should we change renewal pricing for annual contracts?"

- Quantity: renewal rate and downgrade rate

Step 2: Segment before testing

At minimum, split by:

- ICP vs non-ICP

- Monthly vs annual

- New customers vs renewals

Elasticity on renewals is often dramatically different than elasticity on new logos.

Step 3: Run the cleanest test you can

Options (from strongest to weakest):

- A/B price test (randomized)

- Geo or time-boxed test (if randomness is hard)

- Before/after with matched cohorts (least reliable)

Even with a before/after change, cohorts help you avoid mixing customers exposed to different onboarding, product versions, or marketing.

Step 4: Compute elasticity and translate to MRR

Compute elasticity on your chosen quantity metric, then translate:

- How did ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account) change?

- How did new customer volume change?

- What happened to churn and downgrades?

Step 5: Decide with guardrails

Before rolling out broadly, define:

- Maximum acceptable conversion drop

- Maximum acceptable churn increase for affected cohorts

- A rollback plan (especially for self-serve)

The Founder's perspective

A price change is an operational event, not just a number change. Treat it like a launch: define success metrics (ARPA up, churn flat), monitor daily signals (refunds, support tickets), and decide fast if reality diverges from the expected elasticity.

Bottom line

Price elasticity is the simplest way to quantify how much demand you'll lose (or keep) when you change price. But in SaaS, the only elasticity that matters is the one that survives contact with retention.

Use elasticity to size and target price moves, then validate the outcome through MRR movements, ARPA/ASP shifts, and cohort-based churn behavior. That's how founders raise prices with confidence—without accidentally buying short-term revenue at the cost of long-term growth.

Frequently asked questions

Estimate elasticity from a controlled test or a clean before-and-after change. If demand is inelastic, a price increase reduces signups less than the percent price increase, so revenue typically rises. Confirm with downstream retention and expansion, not just checkout conversion.

There is no universal benchmark because elasticity depends on segment, category maturity, switching costs, and how differentiated you are. As a rule, self-serve SMB is usually more elastic than enterprise. Use your own historical tests by plan, channel, and ICP as the baseline.

Start with the decision you are making. For new pricing on a checkout page, measure paid customer conversion. For seat or usage pricing, measure quantity purchased such as seats or usage tiers. Then translate the result into MRR impact using ARPA and retention assumptions.

Short-term elasticity can look favorable while long-term retention elasticity is negative. Common causes include attracting lower-fit customers at the old price, pushing marginal customers into churn after renewal, or creating more downgrades. Always review cohorts and net MRR churn after the change.

Discounts change the effective price, so elasticity based on list price can be misleading. If discounting varies by channel or rep, it also introduces selection bias. Track the realized price (net of discounts) and segment results by discount bands to avoid overestimating pricing power.