Table of contents

MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue)

MRR is the fastest way to answer a founder's most practical question: is the business getting stronger every month, or just busier? Cash in the bank can move because of annual prepay, collections timing, or one-time charges. MRR strips that noise out and shows whether your subscription engine is compounding.

MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue) is the monthly run-rate value of your active recurring subscriptions, expressed in dollars per month, after normalizing different billing periods (monthly, annual, etc.) to a monthly equivalent.

What MRR reveals

MRR is the cleanest "speedometer" for subscription businesses because it ties directly to three outcomes founders manage every week:

Growth quality

Growing MRR via durable customer value (expansion, low churn) is fundamentally different from growing via heavy discounting or short-lived customers. Pair MRR with Net MRR Churn Rate and NRR (Net Revenue Retention) to understand quality.Pricing and packaging leverage

If you change pricing, seat bands, or packaging, MRR is where the impact shows up first—before GAAP revenue trends become obvious. Use MRR alongside ASP (Average Selling Price) and ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account) to see whether growth is coming from "more customers" or "better customers."Planning capacity and burn

MRR is a forward-looking run rate, so it anchors headcount plans and spend guardrails. It also makes metrics like Burn Rate and Burn Multiple interpretable month-to-month.

The Founder's perspective, MRR answers: "If we froze sales today, what recurring revenue base would we carry into next month—and is that base expanding faster than our costs?"

How to calculate MRR

At its simplest, MRR is the sum of your active subscriptions' monthly-equivalent recurring value.

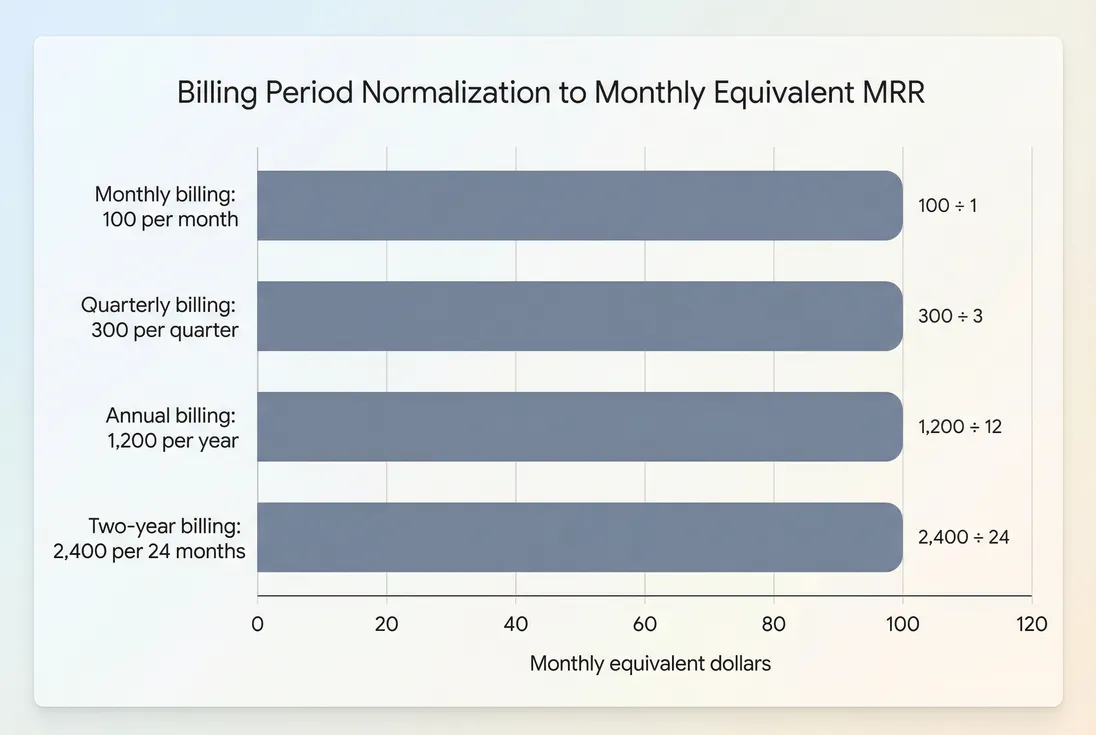

Normalize billing periods

To keep MRR comparable across billing frequencies, convert every recurring subscription to a monthly amount.

Practical examples:

| Plan billed as | Customer pays | Monthly equivalent MRR | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monthly | $100 / month | $100 | Straightforward |

| Quarterly | $300 / quarter | $100 | Divide by 3 months |

| Annual | $1,200 / year | $100 | Divide by 12 months |

| Annual with 20% discount | $960 / year | $80 | Discount reduces MRR if it's on the recurring price |

| 2-year prepaid | $2,400 / 24 months | $100 | Normalize; track cash separately |

Include recurring; exclude one-time

MRR should represent the recurring subscription commitment. Typically:

Include:

- Base subscription fees (monthly/annual)

- Recurring add-ons (extra seats, feature packs) if they are contracted/recurring

- Minimum commitments that recur monthly (even if billed annually, normalize)

Exclude:

- One-time setup/implementation

- Hardware, pass-through fees, and professional services

- One-off overages if they're not committed (see usage-based section below)

For how one-time items behave differently, see One Time Payments.

Handling proration and mid-cycle changes

Founders often get tripped up by upgrades/downgrades mid-month. The clean operational rule is:

- MRR reflects the recurring run rate at a point in time (commonly end of day, end of month), not the invoice amount collected that day.

If you upgrade a customer from $100 to $150 halfway through the month:

- Cash collected might show a prorated invoice.

- MRR should move from $100 to $150 when the new recurring entitlement is effective (based on your system's rules).

This is why looking at movements (new, expansion, contraction, churn) is more actionable than staring at a single MRR total.

If you want a committed view that reduces noise from timing and proration, also track CMRR (Committed Monthly Recurring Revenue).

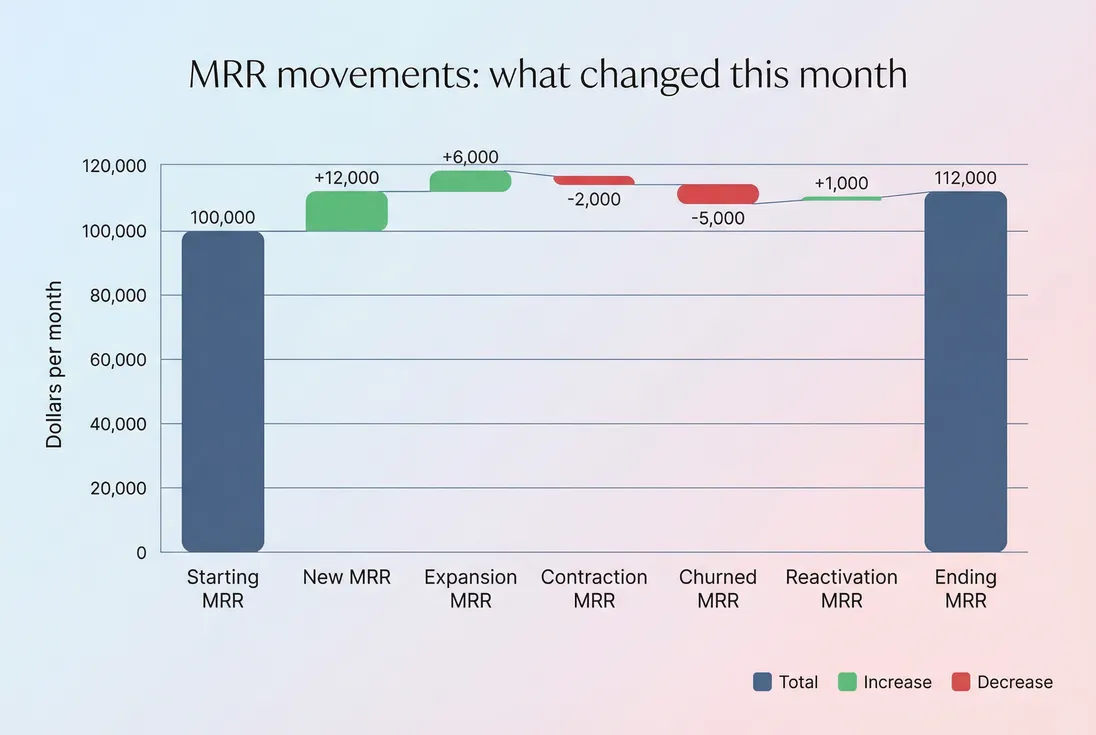

What moves MRR month to month

MRR changes are not mysterious; they come from a handful of repeatable events. A good monthly review always reconciles "starting" to "ending" via movements:

Here's what each movement usually means operationally:

New MRR: new customers started paying.

If new MRR stalls, review lead flow and conversion (Conversion Rate), sales cycle (Sales Cycle Length), and win rate (Win Rate).Expansion MRR: existing customers increased their recurring spend.

Often driven by seat growth, add-ons, or plan upgrades. Deep-dive with Expansion MRR and adoption metrics like Feature Adoption Rate.Contraction MRR: existing customers reduced recurring spend.

Common causes: seat reductions, downgrades, discounting at renewal, or removing add-ons. Track explicitly via Contraction MRR.Churned MRR: customers canceled and recurring revenue went to zero.

Pair with MRR Churn Rate and investigate drivers using Churn Reason Analysis.Reactivation MRR: previously churned customers came back.

Useful for understanding win-back motions and product improvements. See Reactivation MRR.

The Founder's perspective, the movements tell you where to spend your next hour: more pipeline (new), better activation and success (expansion), or fixing product and support gaps (churn/contraction).

The two churn lenses founders confuse

"Churn" gets used loosely. Separate these:

- Customer count churn: how many logos you lost. See Customer Churn Rate and Logo Churn.

- Revenue churn: how much recurring revenue you lost. See MRR Churn Rate and Net MRR Churn Rate.

Revenue churn is often the more strategic lens because losing one large customer can outweigh many small wins—especially if you have concentration risk. See Customer Concentration Risk.

When MRR misleads you

MRR is powerful, but only if you keep it honest. These are the most common failure modes that create "false confidence" (or unnecessary panic).

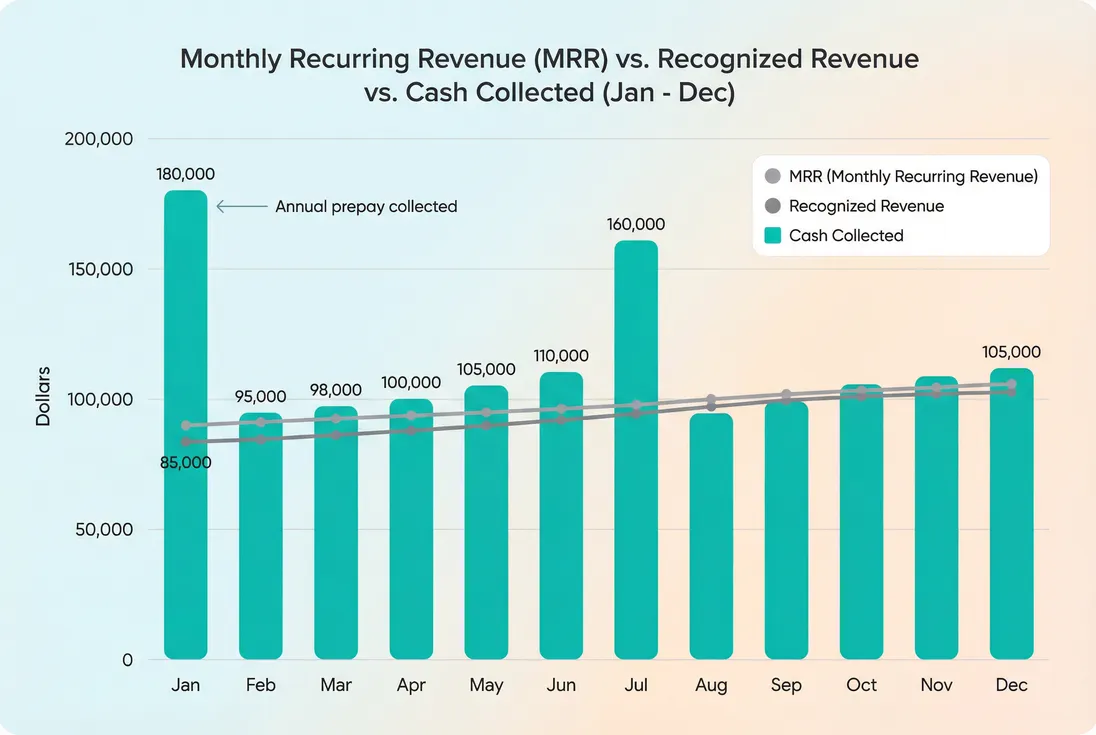

Confusing MRR with cash

Annual prepay makes cash jump but does not increase MRR (beyond the normalized monthly equivalent). A business can look "cash rich" while MRR is flat or shrinking.

If cash timing is a recurring issue (collections, failed payments), layer in finance basics like Accounts Receivable (AR) Aging and subscription accounting concepts like Deferred Revenue.

Not defining how you treat discounts

Discounting can either be:

- A real price change (MRR should go down), or

- A temporary promotion you want to track separately.

The key is consistency. If you treat discounted recurring as lower MRR, you'll see the real economic run rate (good for planning). If you exclude some discounts, your MRR becomes a "list price MRR" and will overstate reality.

For how to think about discount mechanics, see Discounts in SaaS. For a deeper dive into the practical implications, read How should discounts be treated in MRR?

Refunds, chargebacks, and VAT confusion

Refunds and chargebacks affect cash and may affect revenue recognition, but they shouldn't silently distort your MRR definition.

- Refunds: understand whether they represent churn, a billing error, or a concession. See Refunds in SaaS.

- Chargebacks: treat as a collections risk and retention signal. See Chargebacks in SaaS.

- VAT: VAT is not your revenue; avoid counting tax as MRR. See VAT handling for SaaS.

Usage-based pricing edge cases

If you have usage-based components, decide what "recurring" means:

- If usage is variable with no minimum, it is usually not MRR.

- If customers have a contracted minimum (or a predictable platform fee), that minimum can be treated as MRR, with usage tracked separately.

To understand pricing models that create this ambiguity, see Usage-Based Pricing and Metered Revenue. For a practical walkthrough, read Can usage-based pricing be counted as MRR?

Hiding churn behind upsells

A company can post growing MRR while the underlying customer base is deteriorating (high churn masked by expansion or new sales). This shows up when you examine:

- Logo Churn alongside MRR

- Retention by cohort via Cohort Analysis

If your logo churn is rising while MRR grows, you may be turning into a "leaky bucket" that requires ever-increasing acquisition spend to stand still—bad for capital efficiency.

How founders use MRR for decisions

MRR becomes a decision tool when you tie it to specific "if/then" actions.

1) Hiring and runway planning

MRR is not profitability, but it anchors the conversation around capacity:

- If MRR is growing and net retention is healthy, hiring into delivery and success can increase expansion and reduce churn.

- If MRR is flat and churn is rising, hiring more sales reps often increases burn without fixing the constraint.

Pair MRR with Runway and Burn Rate to avoid scaling costs ahead of durable revenue.

The Founder's perspective, "I hire when MRR growth is repeatable and retention is stable—not when I'm optimistic about next quarter's pipeline."

2) Pricing changes and packaging tests

Before you change pricing, decide what success looks like in MRR terms:

- Do you expect higher ARPA? (See ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account))

- Or do you expect fewer customers but higher MRR per customer?

- How much contraction do you expect from downgrades?

After the change, watch:

- Expansion vs contraction mix

- Churned MRR (especially among price-sensitive segments)

- Sales cycle length changes (price can lengthen procurement)

3) Go-to-market focus

MRR by itself doesn't tell you why you're growing. Segment it:

- By plan, channel, or customer size (SMB vs mid-market)

- By geography (to catch concentration or payment behavior differences)

If you use GrowPanel, this is where filters, map, and customer list views help you quickly isolate where MRR is compounding versus where it's fragile. (See Filters and Map.)

4) Retention investment versus acquisition spend

A simple operational heuristic:

- If churned MRR is a meaningful fraction of new MRR, you're running hard to stay in place.

To quantify it, founders often review "gross adds vs losses" using churn and retention dashboards, then decide whether the next investment is:

- onboarding improvements (Onboarding Completion Rate)

- reducing friction (CES (Customer Effort Score))

- success motions to drive expansion (Expansion MRR)

Benchmarks to sanity-check

Benchmarks vary wildly by segment (SMB vs enterprise), pricing model, and maturity. Use these as sanity checks, not goals:

Early-stage (rough heuristics)

- Monthly net new MRR should be consistently positive; volatility is normal, but repeated negative months are a red flag unless intentional (e.g., pricing reset).

- MRR churn: many SMB products struggle above 3–5% monthly; improving below that is meaningful. (Enterprise often targets much lower.)

- Net retention: if expansion exists, push toward strong NRR (Net Revenue Retention); if expansion is minimal, focus on GRR (Gross Revenue Retention).

Growth-stage (what investors probe)

- Is MRR growth driven by new acquisition or by expansion?

- Is churn improving as you scale, or getting worse?

- Do you have whale risk? See Cohort Whale Risk.

If you need a single "health" view, use MRR alongside Net MRR Churn Rate and retention cohorts. That combination catches most "looks good on the surface" issues.

A simple monthly MRR review

This is the practical cadence many founders adopt:

Reconcile the bridge

Starting MRR → movements → Ending MRR. If you can't explain a movement, your data definitions or billing setup need work.Investigate churned and contracted MRR

- top accounts by MRR lost

- churn reasons

- any preventable involuntary churn (see Involuntary Churn)

Validate expansion engine

- expansion MRR by segment and plan

- product adoption signals

- sales-assist vs self-serve upgrade paths

Stress-test with concentration

If a handful of accounts drive a large share of MRR, model what happens if one churns. (See Customer Concentration Risk.)Decide one operational bet

Pick one lever for the next month: reduce churn, drive expansion, or increase new MRR. Don't try to "improve everything" at once.

If you want to see MRR presented as movements and drilldowns, GrowPanel's subscription analytics shows MRR alongside retention, cohorts, and all the metrics you need to understand the full picture. Start with the docs for MRR and MRR movements.

Summary

MRR is your recurring revenue run rate, best managed as a set of movements rather than a single total. Calculate it consistently (normalize billing periods, include true recurring value, define discounts and usage rules), then use movements to make decisions: fix churn, scale expansion, or invest in acquisition—based on what actually moved the business last month.

Frequently asked questions

MRR is a run-rate view of recurring subscription value, normalized to a monthly amount. Your P&L shows recognized revenue under accounting rules, which can lag or lead cash and can include non-recurring items. Use MRR to run the business; use recognized revenue to report performance.

Yes, if they are truly recurring subscriptions. Normalize them to a monthly equivalent by dividing the recurring contract value by the number of months in the billing period. This keeps MRR comparable across billing frequencies. Track cash separately, because annual prepay improves cash but not MRR.

It depends on stage and base. Early-stage companies often target high double-digit monthly growth from a small base, while later-stage companies may be healthy at mid-single digits. The key is pairing growth with retention: strong growth with high churn is fragile and expensive to maintain.

Not necessarily. Cash can rise from annual prepayments, collections improvements, or moving customers from monthly to annual billing. MRR can remain flat because it ignores billing timing. Confirm you are not masking churn with prepayments by reviewing MRR movements and retention alongside cash metrics.

Only if you define a consistent rule. Pure variable usage is better treated as usage revenue rather than MRR, because it is not committed. Many founders either exclude it from MRR or include a conservative baseline. If usage is material, pair MRR with committed metrics like CMRR.