Table of contents

EV/revenue multiple

SaaS founders care about the EV/revenue multiple because it shapes the "price per dollar of revenue" the market is willing to pay for your company—directly affecting dilution in a fundraise, leverage in an acquisition, and how hard you'll be pushed to trade growth for efficiency.

Plain-English definition: the EV/revenue multiple is enterprise value divided by revenue for a defined period (typically last twelve months or next twelve months). It's a shorthand for how investors value your revenue stream given expectations about growth, retention, margins, and risk.

If two companies both have $10M of revenue but one trades at 4x and the other at 12x, the market is saying the second company's revenue is more likely to expand, persist, and convert into cash.

What this multiple is pricing

The EV/revenue multiple isn't just "a valuation metric." In SaaS, it's usually pricing four things:

- Growth durability: not just today's growth, but how likely it is to continue for 2–5 years.

- Revenue quality: stickiness (retention) and expansion (upsell/cross-sell).

- Unit economics and margin potential: especially gross margin and the path to operating leverage.

- Risk: customer concentration, churn volatility, dependence on a single channel, regulatory exposure, and funding risk.

A useful way to think about it: EV/revenue is a compressed opinion about the future. That's why it can move faster than fundamentals.

The Founder's perspective: If your multiple drops, you don't "fix the multiple." You fix the inputs investors are worried about—usually growth durability, retention, and efficiency—and you make those improvements legible in your metrics and narrative.

How it's calculated in practice

There are two pieces: enterprise value (EV) and the revenue denominator.

Enterprise value basics

EV is designed to be capital-structure neutral (so companies with different cash/debt positions can be compared more cleanly). The standard definition:

For public companies, equity value is market cap. For private companies, "equity value" is usually inferred from the latest round price (or an acquisition offer), then adjusted for debt and cash. If you want the deeper mechanics, see Enterprise Value (EV).

The revenue denominator: pick one and be explicit

In public markets, EV/revenue typically uses:

- LTM recognized revenue (last twelve months), or

- NTM revenue (next twelve months) based on guidance/consensus.

In private SaaS, founders and investors often use revenue proxies:

- ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue) as a forward-looking run rate (see ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue))

- MRR x 12 when ARR isn't well-defined (see MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue))

Be careful: EV/ARR is not the same as EV/LTM revenue if you have rapid growth, heavy annual prepay, usage-based variability, or meaningful services. If you're mixing terms, you'll confuse your board (and yourself).

A quick worked example

- EV: $240M

- LTM recognized revenue: $30M

That "8x" becomes meaningful only when compared to businesses with similar growth, retention, and margins—or compared to your own prior quarters.

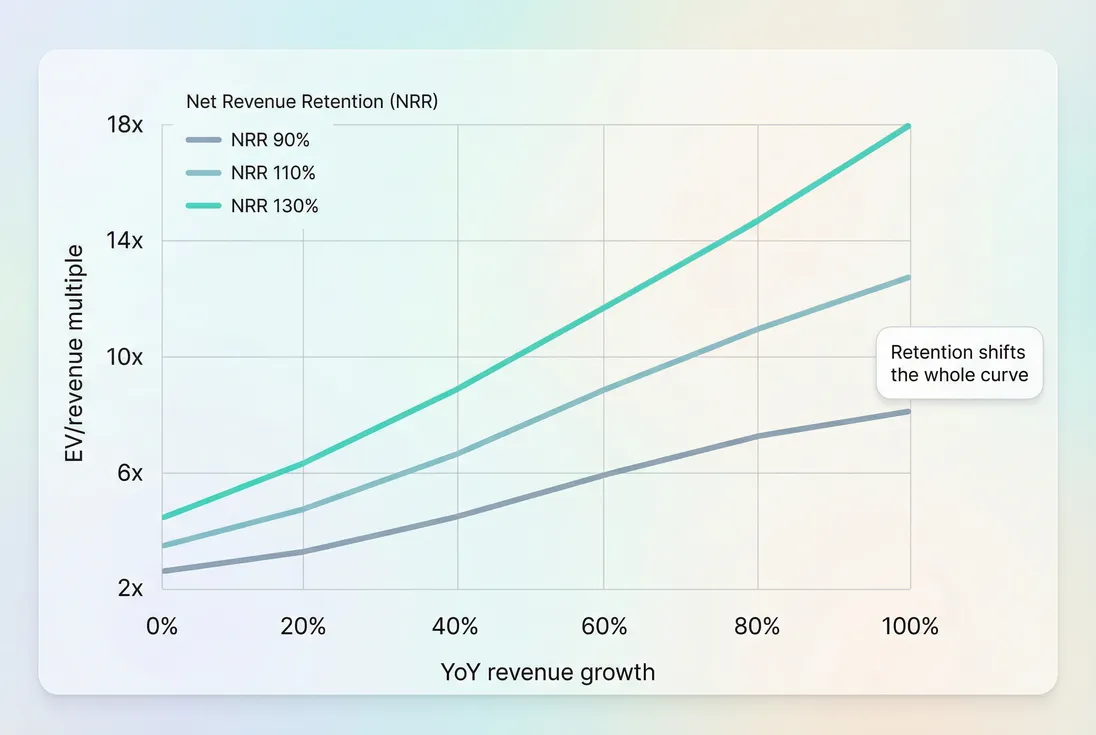

Growth raises the multiple, but retention (NRR) shifts the entire valuation curve—why two companies growing at the same rate can trade at very different EV/revenue.

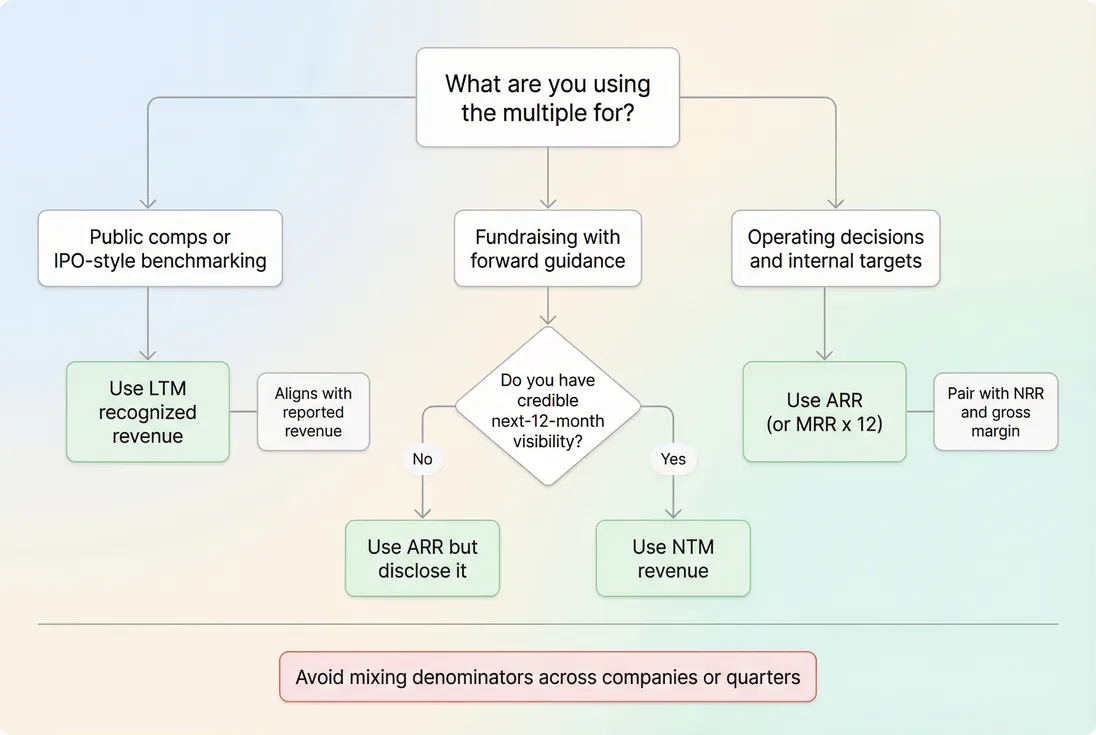

Which "revenue" number to use

Founders get tripped up here because "revenue" is overloaded. Use the denominator that matches the decision you're making.

Use LTM recognized revenue when…

- You're benchmarking to public comps.

- You have meaningful non-recurring components (services, implementation fees).

- You want a clean bridge to accounting measures like Recognized Revenue and Deferred Revenue.

Downside: in fast growth, LTM lags reality and can make your multiple look artificially high.

Use NTM revenue when…

- You're in a growth phase and have credible forward visibility (pipeline + renewals).

- You're comparing to investor conversations that reference forward multiples.

- You have stable renewals and expansion patterns (validated by NRR (Net Revenue Retention)).

Downside: easy to overstate if churn is creeping up or expansion is concentrated in a few accounts.

Use ARR (or MRR x 12) when…

- You sell primarily subscription and want a "run-rate" lens.

- You're translating operating metrics into valuation logic (pricing changes, churn fixes, expansion motions).

- Your board thinks in ARR anyway.

Pair ARR with:

- Gross Revenue Retention (GRR) and NRR (Net Revenue Retention) to prove durability

- CMRR (Committed Monthly Recurring Revenue) if contracts and commitments are central to your story

Rule: whichever denominator you use, state it plainly (EV/LTM revenue, EV/NTM revenue, or EV/ARR) and don't switch mid-deck.

Pick the denominator that matches your use case (public comps, fundraising, or operating decisions) and keep it consistent to avoid misleading multiple swings.

What drives the multiple up or down

EV/revenue moves when either EV changes, revenue changes, or both. In practice, the multiple is most sensitive to forward expectations, not last quarter's close.

The SaaS drivers investors actually react to

1) Growth rate and growth efficiency

- Faster growth generally supports a higher multiple, but only if it's efficient and repeatable.

- Pair the multiple with Burn Multiple and Capital Efficiency to avoid "growth at any cost" blind spots.

If growth is high but burn is extreme, investors often haircut the multiple because future dilution risk is higher.

2) Retention and expansion (NRR and GRR)

This is the biggest "quality of revenue" lever in SaaS.

- Strong GRR (Gross Revenue Retention) reduces downside risk.

- Strong NRR (Net Revenue Retention) increases upside because the installed base grows without proportional CAC.

A common pattern:

- NRR below 100%: investors need new sales just to stand still → lower multiple.

- NRR materially above 110%: compounding base → higher multiple.

3) Gross margin

High gross margin means a larger share of incremental revenue can eventually become operating profit. See Gross Margin and COGS (Cost of Goods Sold).

Watch for:

- Hosting costs scaling faster than revenue

- Support costs rising due to product complexity

- Services embedded in COGS that depress margin

4) Revenue mix and predictability

Markets pay up for revenue that is:

- Recurring

- Contracted or committed

- Low volatility

This is where subscription structure matters: annual contracts, multi-year terms, and low refund/chargeback exposure improve predictability. If refunds or billing issues are material, understand Refunds in SaaS and Chargebacks in SaaS.

5) Risk and concentration

Two companies with identical metrics can trade at different multiples if one has hidden fragility:

- A few accounts drive a large share of revenue (see Customer Concentration Risk)

- Expansion comes from a small number of "whales" (see Cohort Whale Risk)

- Churn is spiky or concentrated in a segment (use Cohort Analysis to validate)

The Founder's perspective: If you want a higher multiple, reduce "single points of failure." Investors pay more for businesses that don't break when one customer, one channel, or one product bet goes sideways.

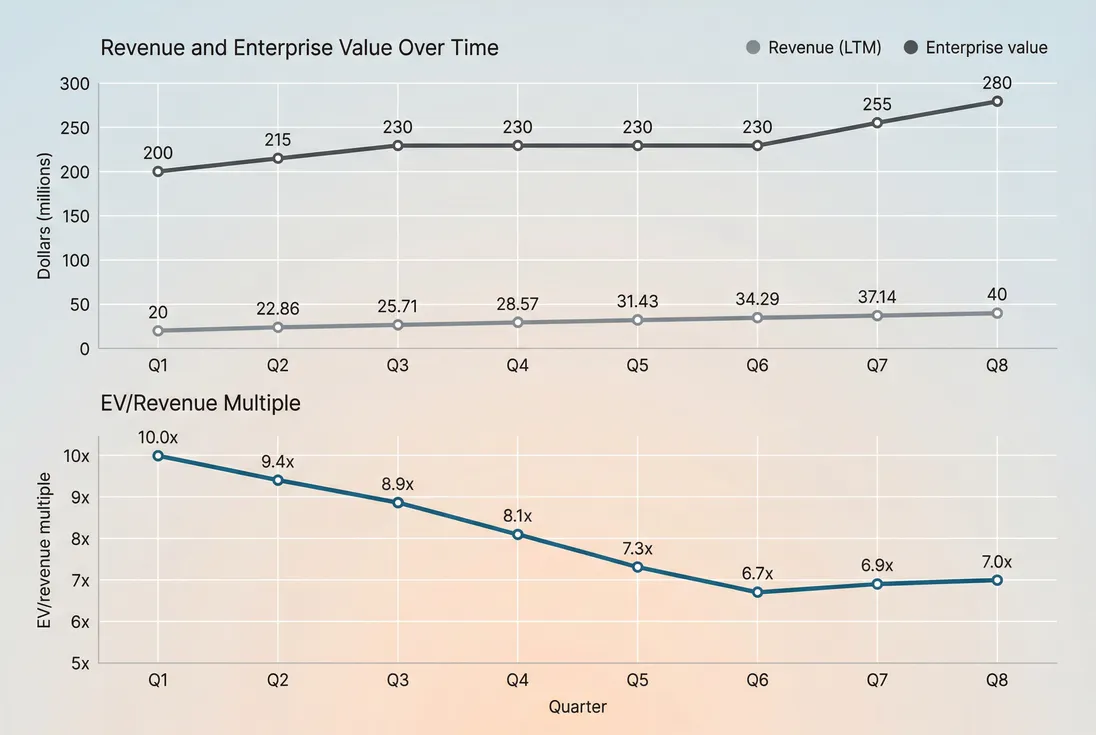

How to interpret changes over time

Founders often read EV/revenue like a scoreboard. It's more useful as a diagnostic.

Multiple expansion: what it usually means

If the multiple rises from 6x to 9x, markets are typically saying:

- Growth is accelerating or becoming more durable

- Retention/expansion improved (NRR up, churn down)

- Margins improved or the path to margins is clearer

- Risk is lower (concentration down, volatility down)

- Or the market regime shifted (rates, liquidity, sector sentiment)

Multiple compression: what it usually means

If the multiple drops from 9x to 6x:

- Growth slowed or is expected to slow

- NRR deteriorated or expansion became less reliable

- CAC efficiency worsened (payback lengthened)

- Gross margin compressed

- Or the market repriced risk broadly

Importantly: your multiple can fall even while the business improves, if the market's required return changes or peers reset.

A simple decomposition: "EV moved" vs "revenue moved"

Track both numerator and denominator each quarter. If revenue grows 40% but EV stays flat, your multiple will mechanically compress.

Separating EV from revenue explains most multiple swings: a flat EV with rising revenue creates mechanical compression, even if fundamentals are stable.

How founders use it in real decisions

1) Fundraising: pricing the round

In practice, EV/revenue helps you translate operational performance into valuation expectations:

- If your retention is improving and gross margin is expanding, you can justify a higher multiple even before revenue fully reflects it.

- If growth is slowing, you can protect valuation by proving durability (NRR/GRR) and efficiency (Burn Multiple, CAC Payback Period).

A tactical approach:

- Present EV/ARR (or EV/NTM revenue) alongside NRR, gross margin, and burn multiple.

- Show the trend line: are these improving quarter-over-quarter?

2) M&A: negotiating leverage

Acquirers often start with EV/revenue, then adjust. You gain leverage by making revenue "feel" safer:

- Low churn and high expansion supported by Retention analysis

- Clean segmentation that explains where growth comes from (SMB vs mid-market vs enterprise)

- Low customer concentration risk (or clear mitigation)

If you're serious about exits, also read M&A Readiness.

3) Pricing and packaging: proving revenue quality

Pricing work can improve the multiple if it increases:

- Net retention (better expansion paths)

- Gross margin (less expensive-to-serve plans)

- Predictability (annual prepay, clearer commitments)

This is where ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account) and ASP (Average Selling Price) help you quantify whether "better revenue" is coming from higher willingness to pay or just discounting (see Discounts in SaaS).

4) Operating plans: setting the right tradeoffs

EV/revenue is not an operating KPI, but it can keep your plan honest. If you need a higher multiple next year (to raise on good terms), your plan must improve the inputs that expand it:

- Retention initiatives that lift NRR

- Margin work that improves gross margin

- GTM changes that shorten CAC Payback Period or raise win rates

- Lower churn via better onboarding and product value realization

The Founder's perspective: Use the multiple to force clarity on "what has to be true" for your next round. Then translate that into 2–3 operating bets (retention, margin, efficient growth) with measurable targets.

Practical benchmarks (with caveats)

Multiples vary by market cycle, interest rates, and sector sentiment. So treat benchmarks as ranges for sanity checks, not a score to chase.

A simple heuristic table (for subscription-heavy SaaS with reasonable gross margins):

| SaaS profile (simplified) | Typical growth/quality signals | Common EV/revenue range |

|---|---|---|

| Slower growth, mature | modest growth, strong margin focus, steady GRR | ~2x–6x |

| Solid growth, credible retention | good NRR, improving efficiency | ~6x–10x |

| High growth, high quality | strong NRR, large market, durable expansion | ~10x–15x+ |

What pushes you toward the top of your band:

- High and stable NRR

- Strong gross margin with operating leverage potential

- Low concentration and predictable renewals

- Efficient growth (burn multiple improves while growth holds)

When the metric breaks (and what to do)

1) Early-stage noise

If revenue is small, the multiple can be meaningless. Small denominator changes swing the ratio dramatically. Use it sparingly until revenue is large enough to be stable, and rely more on retention cohorts and unit economics.

2) Services or one-time revenue mix

If implementation or services are meaningful, EV/revenue comparisons to "pure SaaS" get distorted. Separate recurring from non-recurring revenue and consider how margins differ.

3) Usage-based volatility

Usage-based pricing can be great, but revenue can be less predictable. Investors will focus harder on:

- Cohort stability

- Expansion concentration

- Gross margin under high usage

4) Accounting and cash timing confusion

Annual prepay affects cash, not recognized revenue. If you're mixing billing and revenue, you'll misread the multiple. Use Deferred Revenue to reconcile.

5) Misleading improvements from discounting

Discounts can inflate "new logo growth" while weakening revenue quality. Monitor discounting explicitly (see Discounts in SaaS) and validate whether retention improves.

A founder's checklist for using EV/revenue well

- Define EV consistently (equity value basis, debt, cash).

- Choose a denominator (LTM, NTM, or ARR) and stick to it.

- Always pair it with:

- NRR (Net Revenue Retention)

- Gross Margin

- Burn Multiple (or at least burn rate and runway; see Burn Rate and Runway)

- Explain changes as EV-driven vs revenue-driven.

- Use it quarterly, not weekly. Multiples are slow-feedback signals tied to expectations.

Used correctly, EV/revenue doesn't just tell you what you're worth today—it tells you what the market believes about the durability of your growth. Your job is to either make that belief true, or prove it's already true in the numbers.

Frequently asked questions

There is no single good number. The right multiple depends mostly on growth rate, net revenue retention, and gross margin, plus risk factors like customer concentration. As a rough sanity check, slower-growth SaaS often trades in low single digits, while durable high-growth SaaS can command high single to low double digits.

Strictly speaking, EV/revenue uses recognized revenue, usually LTM or NTM. In venture conversations, many people casually say EV/ARR because ARR is more forward-looking for subscription businesses. If you use ARR, be explicit and consistent, and sanity-check it against recognized revenue and deferred revenue dynamics.

Multiples often compress when revenue grows faster than enterprise value, or when investors mark down risk. Common causes include slowing growth, weaker net revenue retention, higher churn, margin pressure, or rising burn. A falling multiple is a market signal about future expectations, not a verdict on current revenue quality alone.

Buyers use it as a fast screen, then adjust based on profitability, retention, and integration risk. A high multiple usually requires strong expansion, low churn, high gross margin, and a credible path to cash flow. If the business relies on heavy services or one-time revenue, buyers will haircut the revenue base.

Yes, because the multiple reflects expected future cash flows and risk. Improving net revenue retention, reducing churn, raising gross margin, lowering customer concentration, and demonstrating efficient growth can raise investor confidence and valuation even before revenue fully reflects the change. The key is proving durability, not just making projections.