Table of contents

Customer concentration risk

A single churn email from your biggest customer can erase a quarter of your run-rate overnight—changing hiring plans, runway, and even your fundraising story. Customer concentration risk is the metric that tells you how exposed you are to that kind of "one-account shock."

Customer concentration risk measures how much of your revenue (usually MRR or ARR) is concentrated in a small number of customers—most commonly the top 1, top 5, or top 10 accounts. The higher the concentration, the more your business performance depends on a few relationships.

If you want a companion concept focused on the distribution itself (not the risk framing), see /academy/customer-concentration/. For baseline definitions of run-rate revenue, start with /academy/mrr/ and /academy/arr/.

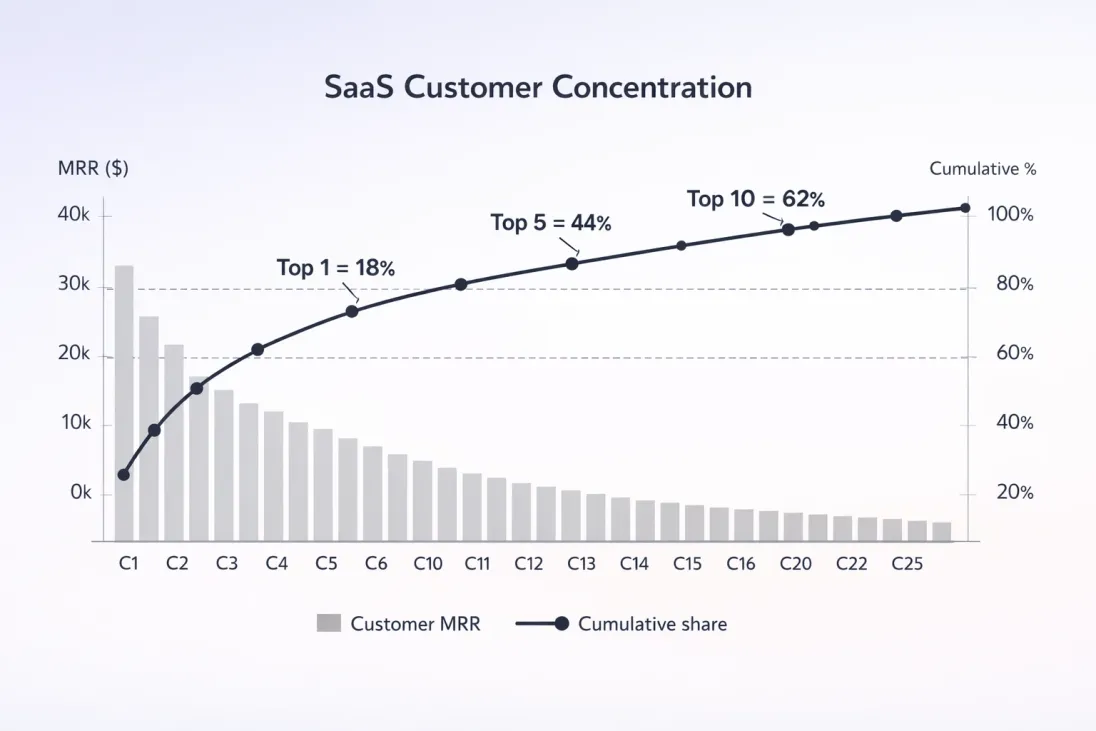

A Pareto view makes concentration obvious: you're looking for how quickly the cumulative line reaches 50–80% of revenue as you move through top customers.

What this metric reveals

Customer concentration risk answers a founder-level question: "How fragile is my revenue if I lose one relationship?"

It shows up in three places that matter operationally:

Runway volatility

If 20% of MRR sits in one account, you don't just have churn risk—you have budget risk. One procurement decision can force layoffs or freeze growth spend.Forecast integrity

Concentrated revenue makes forecasts "lumpy." Expansion from one customer can mask weakness elsewhere; churn from one customer can hide genuine product-market fit in a segment.Negotiation leverage

The more you depend on an account, the more they can push discounts, custom terms, and support burden—often subtly, renewal after renewal.

The Founder's perspective

If you can't say "we would still be fine if our biggest customer left," your strategy isn't just growth—it's risk management. Concentration should directly influence how aggressively you hire, how you discount, and how early you diversify acquisition channels.

How to calculate it

There isn't one universal formula. In practice, founders track two simple measures plus one "distribution" measure for deeper rigor.

Top customer share (top 1, 5, 10)

This is the most actionable version: how much of total MRR (or ARR) is held by your biggest accounts.

Interpretation:

- If top-1 share rises, your downside from one churn event increases.

- If top-5 or top-10 share rises, you're drifting toward "few-big-accounts" economics—more like enterprise services risk, even if you sell software.

Tip: calculate this on MRR for operational risk. If you sell annual contracts, also review it on ARR to align with board/investor conversations (see /academy/arr/).

Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI)

HHI captures concentration across all customers, not just the top few. It's widely used in other industries to describe market concentration, and it works well for SaaS revenue distribution too.

Where Share(i) is customer i's share of total MRR (or ARR), expressed as a decimal (for example, 0.18 for 18%).

Why it's useful:

Top-5 share can stay flat while risk increases (for example, the top customer grows and customers 4–10 shrink). HHI will usually catch that shift because large shares are squared.

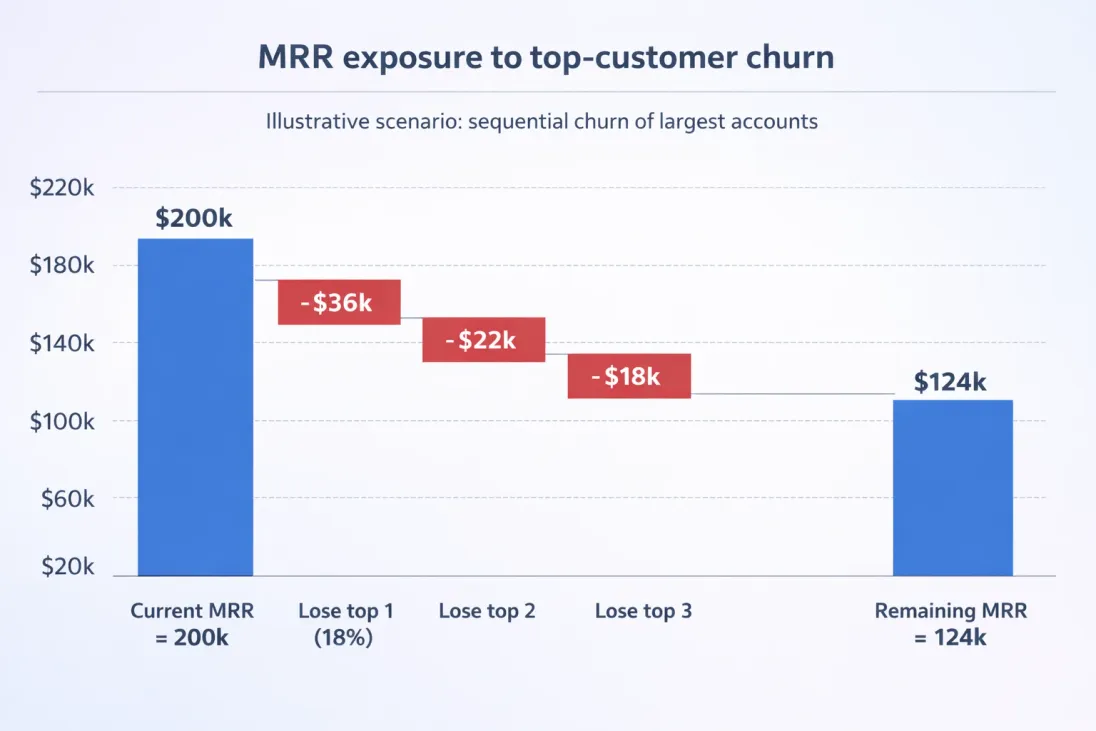

A simple "shock test" (optional)

Founders often want a plain answer: "If my top customer churns, what happens?"

This is not a replacement for a concentration metric, but it's a powerful communication tool for planning and board decks.

A shock test translates concentration into a planning number: "what's the new run-rate if we lose the biggest account(s)?"

What drives concentration up or down

Concentration is not random—it's usually a predictable byproduct of strategy and execution.

Things that increase concentration (often unintentionally)

1) Landing enterprise faster than you can scale distribution

Early enterprise wins can dominate revenue before you've built repeatable demand generation or a broad outbound engine. Your "customer count" grows, but your revenue doesn't diversify.

2) Heavy discounting for logos

A few large deals negotiated with bespoke pricing can create dependence because you over-invest in keeping them.

3) Product roadmaps that favor one account

If your biggest customer funds feature development (explicitly or implicitly), you may end up with a roadmap that reduces appeal to the rest of the market—making diversification harder.

4) Expansion concentrated in a few accounts

If your /academy/nrr/ is driven mostly by 1–3 "whales," your growth is less resilient than NRR implies.

For more on this dynamic, see /academy/cohort-whale-risk/.

Things that reduce concentration (the "right" way)

1) More customers at the same price point

This is the cleanest fix: grow your customer base while keeping pricing consistent. It tends to improve resilience without changing your model.

2) A clear mid-market or SMB motion

If you can sell smaller contracts with lower sales friction, revenue distribution usually widens.

3) Packaging that caps single-account dominance

Usage-based pricing can increase concentration if one customer scales usage faster than others. But packaging can also reduce concentration if it encourages broad adoption across many customers rather than extreme expansion in one.

4) Product-led expansion across many accounts

Expansion is great when it's diversified. In many SaaS businesses, the healthiest pattern is a wide base of accounts expanding modestly rather than a few expanding massively.

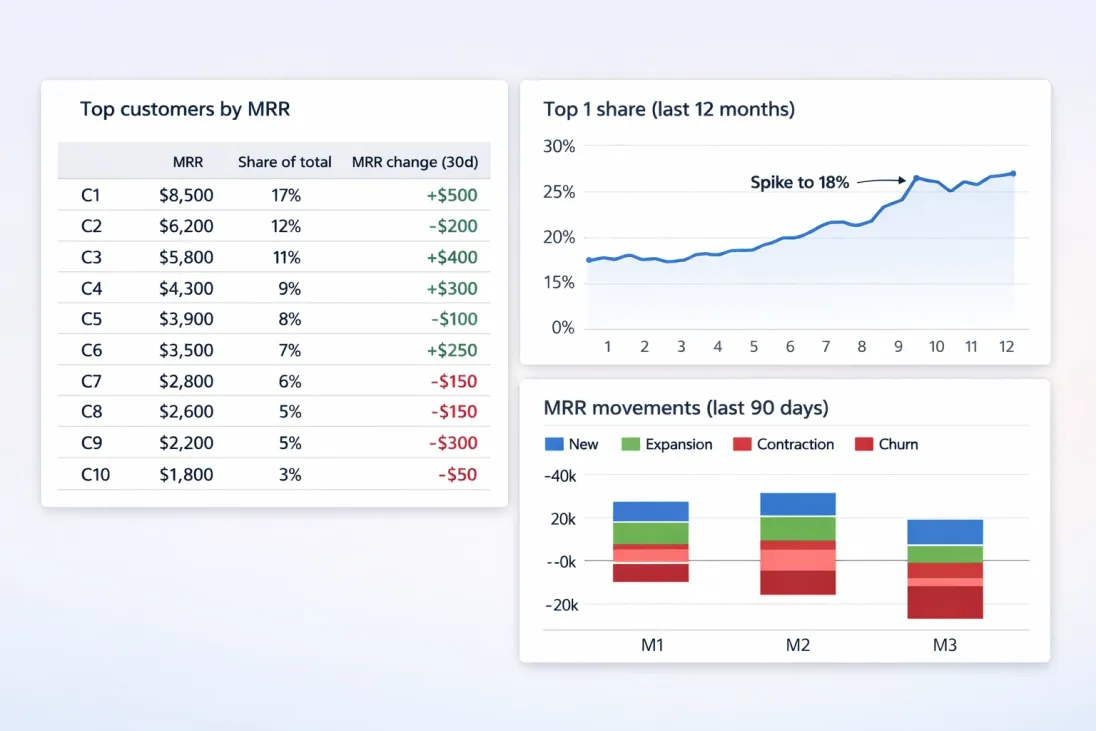

How to interpret changes month to month

A concentration number is easy to calculate and easy to misread. The key is to connect the change to what actually happened: new sales, expansions, contractions, or churn.

A quick interpretation guide

| What changed | What it usually means | What to check next |

|---|---|---|

| Top-1 share up | Biggest customer expanded or others shrank | Expansion source, discounting, product dependency |

| Top-5 share up | Enterprise motion accelerating vs rest | Pipeline mix, segment CAC, staffing allocation |

| HHI up but top-5 flat | Distribution is becoming less even | Mid-tier contraction, small customer churn |

| Top-10 share down | Diversification improving | Whether growth is efficient and repeatable |

| Concentration down due to churn | Risk reduced, but at a cost | Net MRR churn and growth efficiency |

To diagnose drivers, you want a view of MRR movements (new, expansion, contraction, churn). If you're using GrowPanel, the MRR movements and filters make it straightforward to isolate what changed (for example: enterprise segment only, or a specific plan), and the customer list helps you see which accounts moved. See /docs/reports-and-metrics/mrr-movements/ and /docs/reports-and-metrics/filters/.

Don't confuse "contract protection" with "dependency reduction"

Multi-year contracts, prepaid annuals, and strong procurement relationships can reduce short-term churn likelihood, but they do not eliminate concentration risk. They mainly shift it in time.

Practical example:

- A 3-year agreement may make next quarter safer.

- But if the customer is 25% of ARR, renewal risk becomes a major event when it arrives—often with larger discount pressure.

That's why concentration should be reviewed alongside:

- /academy/average-contract-length/

- /academy/renewal-rate/

- /academy/gross-revenue-retention/ and /academy/nrr/

Reasonable thresholds and benchmarks

There's no single "safe" number, but you can set decision thresholds—points where behavior changes (hiring, discount approvals, pipeline diversification).

A practical starting point (MRR-based)

These are not universal benchmarks; they're operating guidelines many founders use:

| Business model | Top-1 share | Top-5 share | How to think about it |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMB / self-serve | < 5% | < 15–25% | Revenue should be widely distributed; one churn shouldn't matter much |

| Mid-market | 5–10% | 20–35% | Some concentration is normal; watch top-customer expansion dependency |

| Enterprise | 10–25%+ | 35–60%+ | Concentration can be acceptable if renewals are proven and pipeline is deep |

Two clarifications founders often miss:

- High concentration is normal early. If you have $30k MRR and one customer pays $6k, your top-1 share is 20%. That doesn't mean you're failing—it means your next priority is diversification, not just growth.

- Segment matters more than stage. An "SMB product" with 30% of revenue in one customer is a red flag. An enterprise product with 30% in one customer may be survivable if the account is stable and repeatability is proven.

The Founder's perspective

Treat thresholds like policy triggers. For example: "If top-1 exceeds 15%, we pause net-new hiring until we have 2 quarters of diversified pipeline" or "discounts over 20% require a plan to reduce top-1 share within two quarters."

How founders reduce concentration risk

You don't reduce concentration by obsessing over the metric—you reduce it by changing the inputs: who you sell to, how you price, and how you retain.

1) Build a second "revenue engine"

The most reliable fix is adding a second repeatable acquisition motion:

- a new segment (SMB → mid-market, or mid-market → enterprise),

- a new vertical,

- or a new channel.

The goal isn't diversification for its own sake; it's ensuring that your growth does not require one account to say yes.

What to do this quarter:

- Audit pipeline coverage by segment (see /academy/pipeline-coverage/).

- Commit headcount to the second motion (even if small), so it doesn't lose in prioritization fights.

2) Stop "custom work as a growth strategy"

If your biggest customers require bespoke implementations, you're often building services-like dependency:

- higher switching costs (good),

- but also higher support burden and roadmap capture (bad),

- and fewer customers you can serve with the same product.

A practical rule: if a feature is requested by one whale, require evidence it will help the next 10 customers you want.

3) Tighten discounting and terms

Discounting can increase dependence because it:

- trains procurement that you'll cave,

- and raises the "renewal cliff" later.

If you do discount, anchor it to something that reduces risk:

- longer term,

- broader rollout,

- or a pricing structure that can scale across many customers (not one).

For discount hygiene, see /academy/discounts/ and related unit economics in /academy/ltv-cac-ratio/.

4) Diversify expansion, not just acquisition

A dangerous pattern is: new sales are okay, but expansion MRR comes from 1–2 accounts.

What to do:

- Review expansion sources by customer tier (top 10 vs everyone else).

- Invest in enablement, in-app prompts, and customer outcomes that scale across many accounts.

- Use cohort views to see if expansion is broad-based (see /academy/cohort-analysis/).

If you're analyzing in GrowPanel, start from cohorts and retention, then drill into the customer list for which accounts are driving expansion. See /docs/reports-and-metrics/cohorts/ and /docs/reports-and-metrics/retention/.

5) Manage "key account" risk like a portfolio

If you are concentrated (common in enterprise), operate accordingly:

- executive sponsor per top account,

- pre-renewal value reviews,

- multi-threading (multiple champions),

- and early renewal risk detection.

Pair this with churn understanding (see /academy/churn-reason-analysis/) so you're not surprised by preventable churn drivers.

Concentration becomes actionable when you track it alongside who the top customers are and what drove recent MRR movements.

When concentration is acceptable

High concentration isn't automatically bad. It can be a rational phase if:

- Your ICP is inherently concentrated (true enterprise, limited buyer universe).

- Retention is proven in the same tier (strong GRR/NRR across multiple large accounts, not just one).

- Pipeline is deep enough that losing a whale doesn't end growth.

- Your product is sticky in ways that don't depend on a single champion.

The red flag is not "top-1 share is high." The red flag is: top-1 share is high and you don't have an operating plan for it.

A simple operating cadence

For most founders, this cadence is enough to stay ahead of concentration risk without over-analyzing it:

- Weekly (15 minutes): review top customers and any meaningful MRR changes (expansion, contraction, churn).

- Monthly: compute top-1, top-5, top-10 share and review the direction.

- Quarterly: run shock tests (lose top 1, lose top 3) and pressure-test hiring and spend plans.

If concentration is rising, don't just "watch it." Pick one lever (diversify acquisition, reduce discounting, broaden expansion) and make it a quarterly objective.

Frequently asked questions

It depends on your go-to-market. SMB self-serve businesses often aim for a low top-1 share (roughly under 5%) and top-10 under ~20–30%. Enterprise SaaS can tolerate higher concentration, but should offset it with strong renewal proof, multi-year terms, and a credible path to diversification.

Track both if you sell annuals. MRR shows operational exposure (what happens to your monthly run-rate if a customer churns). ARR is useful for boards and financing narratives. If you have big annual prepayments, MRR can look stable while renewal risk is still high—so review renewal calendars too.

Growth from a large customer is good only if it's "healthy" expansion (broad adoption, multiple stakeholders, embedded workflows) rather than discount-driven or champion-driven. As their share rises, your downside from a single churn event increases. Pair expansion with a diversification plan and executive-level renewal management.

They look for (1) top-1 and top-5 revenue share, (2) retention history for large accounts, (3) contract terms and renewal timing, and (4) whether growth is replicable beyond one segment or channel. High concentration isn't fatal, but it raises diligence depth and can reduce valuation multiples.

Start by preventing "accidental enterprise" dependency: stop one-off custom work, standardize packaging, and tighten discounting. Then build repeatable acquisition in a second segment (mid-market, another vertical, or another channel). Operationally, strengthen onboarding and retention to reduce logo churn while scaling acquisition.