Table of contents

Customer concentration risk

A single customer can make your quarter—or break your year. Customer concentration risk is the hidden volatility behind "great growth" when too much of your revenue depends on a handful of accounts.

Customer concentration risk is the degree to which your revenue (typically ARR or MRR) is dependent on your largest customers. The higher the concentration, the more a single churn, downgrade, delayed renewal, or procurement freeze can swing your growth rate, cash planning, and valuation.

What this metric reveals

Concentration risk answers one practical question: If one customer sneezes, do we catch pneumonia?

It matters because it influences:

- Forecast reliability: One renewal becomes the forecast.

- Cash planning: One delayed payment changes hiring plans.

- Product strategy: Big customers can pull you into bespoke work.

- Go-to-market focus: High concentration often signals a narrow ICP or a lopsided channel.

- Valuation and financing: Investors discount revenue that looks like a single contract wearing a SaaS mask.

If you're already tracking /academy/arr/ or /academy/mrr/, concentration is the "distribution" layer on top of those totals.

The Founder's perspective

Concentration risk isn't about whether you like enterprise. It's about whether you can survive one account's decision. Your job is to (1) quantify the blast radius and (2) put mitigation in place before you need it.

How to calculate it (without overthinking)

There are a few common ways to measure concentration. Use at least two: a simple "top share" metric and one distribution metric.

Top customer share (the fastest signal)

This is the number boards ask for because it's intuitive.

You should also compute top 3, top 5, and top 10:

HHI (distribution-sensitive)

Top-customer share misses a common failure mode: you can have "no whales" but still be overly dependent on a small set of mid-sized customers. The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) captures how concentrated the whole book is.

- If revenue is evenly spread across many customers, HHI is low.

- If a few customers dominate, HHI rises quickly because shares are squared.

You don't need perfect math hygiene to benefit—HHI is mainly useful for tracking directionally over time.

Step-by-step workflow (what to actually do)

- Export a customer list with current ARR (or MRR) per customer.

- Sort descending by ARR.

- Compute:

- Top 1 share

- Top 5 share

- Top 10 share

- Optional: HHI

- Repeat by segment (SMB, mid-market, enterprise) and by key dimensions (industry, region, channel).

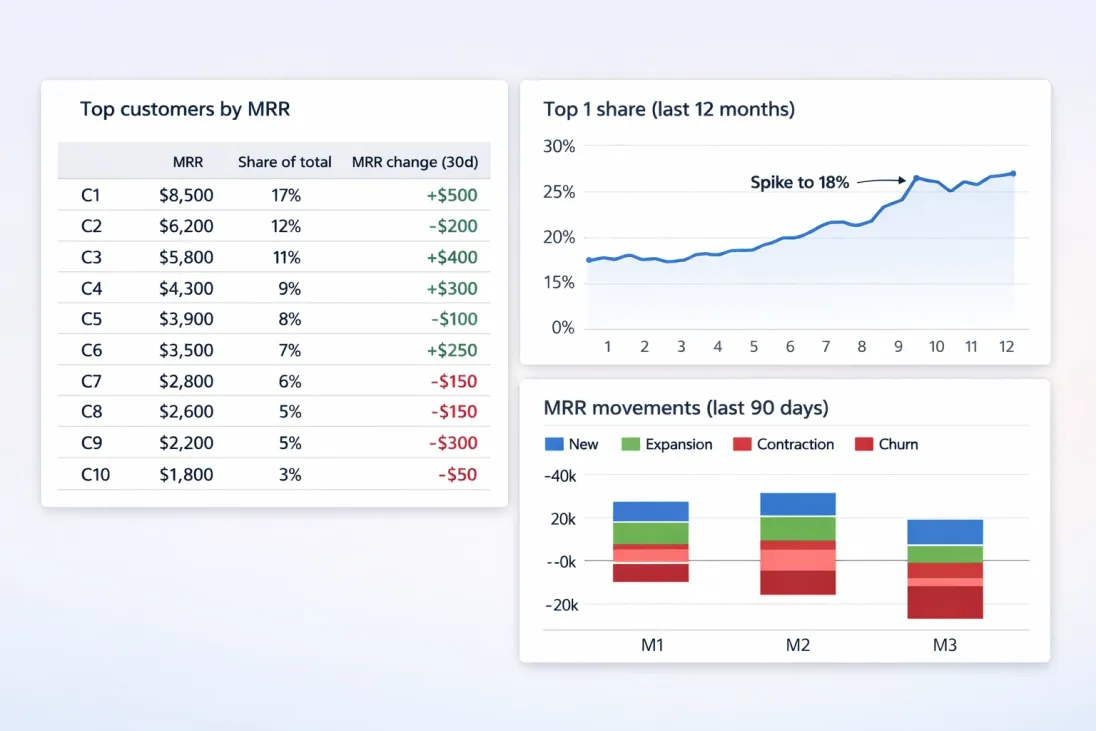

If you're using GrowPanel, you can typically do this by starting from the customer list and applying filters to isolate segments, then validating the drivers using MRR movements (expansion vs contraction vs churn). See /docs/reports-and-metrics/filters/ and /docs/reports-and-metrics/mrr-movements/.

What "good" looks like (practical thresholds)

Benchmarks vary by market. A security company selling to Fortune 500 will look different from a self-serve PLG tool.

Use thresholds as decision triggers, not report-card grades.

| Company context | Largest customer share (rough) | Top 5 share (rough) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early B2B (pre-PMF) | 20–40% | 50–80% | Common; survival depends on renewal timing and diversification plan |

| Post-PMF (growing mid-market) | 10–20% | 30–60% | Acceptable if retention is solid and pipeline is broad |

| Enterprise-heavy, multi-year | 10–25% | 40–70% | Higher can be okay if contracts are long, renewals de-risked, and expansions diversified |

| Mature SaaS with broad base | <10% | <30–40% | Lower volatility; less single-thread risk |

Two adjustments founders often miss:

- Contract structure changes the risk. A 3-year agreement with clear renewal terms is not the same as a monthly cancellable plan.

- Retention quality changes the risk. Strong /academy/nrr/ and stable /academy/grr/ can offset higher concentration, because the "blast probability" is lower.

The Founder's perspective

If your largest customer is 25% of ARR, that's not automatically "bad." It just means you should run the business like you have a single high-stakes renewal—because you do.

Seeing concentration at a glance

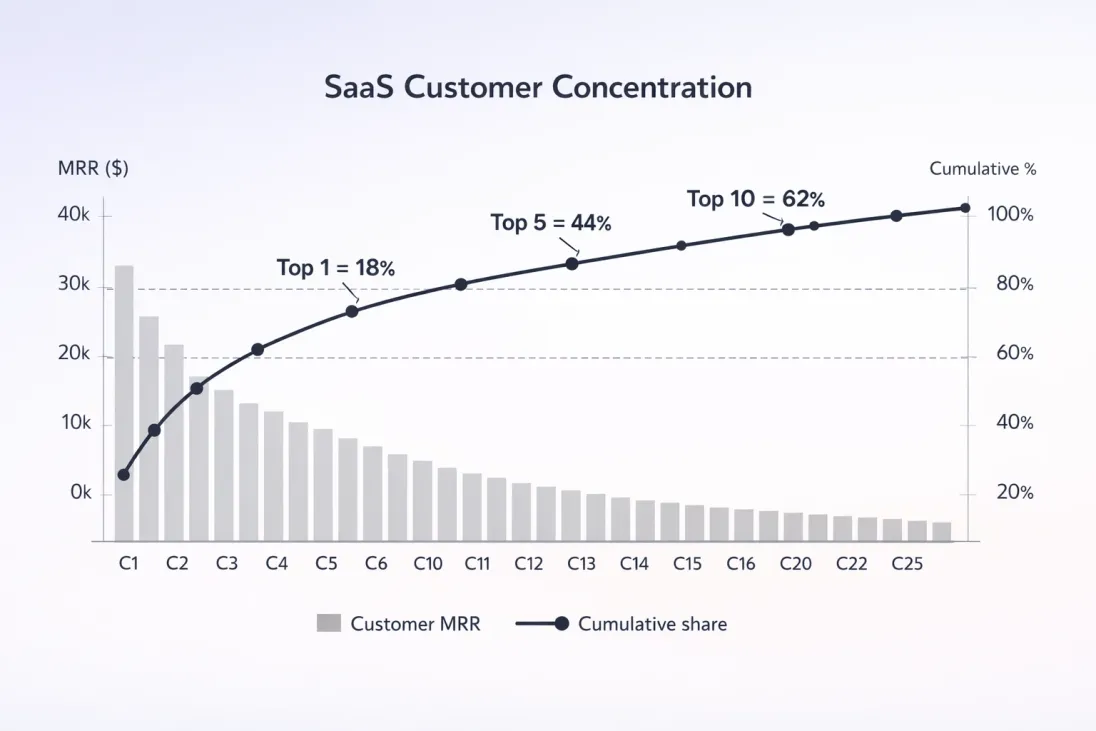

A Pareto view makes concentration obvious: you can see how quickly a few customers add up to most of ARR.

What drives concentration up or down

Concentration changes for reasons that are usually strategic, not accidental. Here's how to interpret movement.

Why concentration increases

- Landing an enterprise whale: Great for revenue, increases dependency immediately.

- Expanding existing big accounts faster than acquiring new ones: Often happens when sales headcount is limited.

- Churn in the long tail: If many small customers churn, whales become a bigger share even if they didn't grow.

- Pricing and packaging that favors large accounts: Seat-based tiers and minimum commitments can amplify top-end share.

Interpretation: Rising concentration isn't inherently negative; it can be a sign you're moving upmarket. The problem is when the risk controls (contract terms, customer success coverage, product scalability) don't mature at the same pace.

Why concentration decreases

- Healthy new customer acquisition: Especially in the segment below your whales.

- Standardized packaging that scales: Less bespoke selling leads to more "repeatable" mid-market volume.

- Expansion spreading across many accounts: Instead of one champion driving all upsell.

Interpretation: Falling concentration usually improves resilience, but check you didn't achieve it by failing to expand your best-fit enterprise customers.

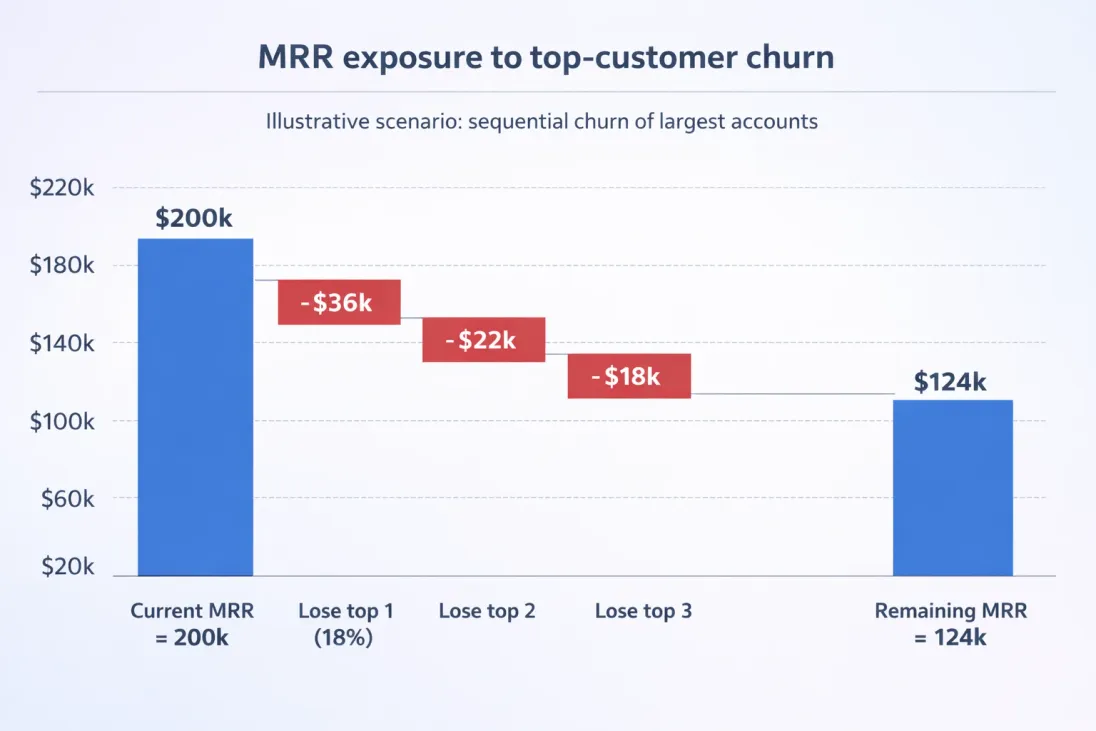

The real question: what's the blast radius?

Founders should translate concentration into an "impact scenario" that connects to operating decisions: hiring pace, burn, and growth expectations.

A simple approach:

- Identify the largest customer (or top 3).

- Model:

- What happens if they churn?

- What happens if they downgrade by 30%?

- What happens if renewal is delayed by 90 days?

Then connect that to your financial reality: burn and runway (see /academy/burn-rate/ and /academy/burn-multiple/).

Concentration becomes actionable when you translate it into a scenario: what does one churn event do to ARR, and how much new ARR you'd need to offset it?

The Founder's perspective

If losing one customer forces layoffs, you're not measuring concentration risk—you're living it. Use the blast radius model to set a diversification target and a timeline, then staff sales and success accordingly.

When this metric "breaks" (common mistakes)

Mistake 1: measuring only by logos

Logo count hides revenue dependency. Ten "big logos" can still be one budget decision away from trouble.

Pair concentration with:

- /academy/arpa/ (to see if your average masks whales)

- /academy/customer-concentration/ (for distribution concepts)

- /academy/cohort-whale-risk/ (to see if a cohort is dominated by a few accounts)

Mistake 2: using invoiced cash instead of ARR

Collections timing can temporarily understate exposure. Use ARR/MRR for dependency, and separate cash risk via AR metrics (see /academy/ar-aging/) if needed.

Mistake 3: ignoring renewal timing

Two companies can both have 20% top-customer share, but:

- Company A has a 36-month contract, renewal in 18 months.

- Company B is month-to-month.

Same concentration number, radically different risk.

Mistake 4: assuming expansion reduces risk

Expansion can increase concentration if it's dominated by your top 1–3 accounts. Validate whether expansion is broad-based using expansion concepts (see /academy/expansion-mrr/).

How founders use it to make decisions

1) Set explicit concentration guardrails

Pick a guardrail that matches your stage and sales motion, for example:

- Largest customer ≤ 15% of ARR

- Top 5 customers ≤ 45% of ARR

Then define actions when breached:

- Increase mid-market acquisition targets for the next quarter

- Reduce custom work for the largest account

- Strengthen renewal plan and executive sponsor coverage

This is less about "hitting a benchmark" and more about making risk visible early enough to respond.

2) Decide when to accept a whale

Sometimes the whale is the right call. If you take it, make the trade explicit and negotiate accordingly:

- Term: push for multi-year (even if billed annually)

- Renewal mechanics: notice periods, early renewal incentives

- Scope and services: minimize bespoke commitments that create delivery risk

- Expansion rights: pre-negotiate pricing bands for growth

- Dependency reduction: commit internally to a diversification plan

A whale with weak terms is concentration risk. A whale with strong terms is a growth asset.

3) Align product strategy with concentration reality

High concentration often correlates with product decisions:

- Too much revenue in one customer can pressure you into customer-specific features.

- That can slow roadmap delivery and hurt retention in the broader base.

Use concentration as a forcing function:

- "Is this request reusable across our next 20 customers?"

- "Does this increase switching costs for one account or improve the product for the segment?"

4) Shape your go-to-market mix

Concentration can be managed through deliberate mix:

- Enterprise deals for ARR growth

- Mid-market volume to dilute dependency

- Partnerships and self-serve to broaden the base

This is where distribution by segment matters.

Segmenting concentration shows where risk actually comes from—often one segment (like enterprise) dominates the exposure even if total growth looks healthy.

The Founder's perspective

Your goal isn't "no concentration." Your goal is "concentration we can withstand." Segment-level concentration tells you whether to hire more enterprise CS, invest in mid-market acquisition, or tighten deal terms.

How to reduce concentration risk (playbook)

You can't spreadsheet your way out of concentration; you need operating moves.

Reduce dependency (portfolio moves)

- Add breadth below your whales: Build a repeatable motion for the segment one step down-market.

- Diversify acquisition channels: If all big deals come from one partner, you've created a second concentration problem.

- Avoid one-customer expansion dominating growth: Set targets for expansion across the top 20 accounts, not just the top 3.

Reduce the probability of loss (retention moves)

- Build a renewal calendar with executive sponsor assignments.

- Track health and adoption for top accounts; don't wait for procurement to surprise you.

- Invest in retention systems (see /academy/retention/ and /academy/churn-reason-analysis/).

Reduce the impact (contract and product moves)

- Multi-year terms, clear renewal windows, and structured price increases reduce volatility.

- Standardize packaging to prevent one customer from "owning" a feature.

- Limit SLA and custom commitments that turn a renewal into a negotiation.

What to report to your board (simple, credible)

A strong monthly or quarterly concentration update is:

- Top customer share and top 5 share (ARR)

- Changes since last period and why (new deal, expansion, churn in tail)

- Renewal timeline for top accounts (next 180 days)

- Mitigation plan (pipeline + retention actions)

Keep it operational. Concentration is only scary when it's unexplained and unmanaged.

Quick checklist

Use this to operationalize concentration risk in under an hour:

- Compute top 1, top 5, top 10 ARR concentration monthly

- Break out by segment and channel

- Track renewal windows for top accounts

- Run a churn/downgrade blast radius scenario quarterly

- Set a guardrail and a trigger-based response plan

- Confirm your biggest expansions aren't coming from only 1–2 accounts

If you want the concept adjacent to this one, see /academy/customer-concentration/ for distribution framing, and pair it with /academy/nrr/ to understand whether big-account growth is offsetting churn elsewhere.

Frequently asked questions

Early-stage SaaS often has higher concentration because a few early wins dominate revenue. As a rule of thumb, try to keep your largest customer under 20 percent of ARR by Series A, and under 10 percent by Series B. Context matters: regulated enterprise markets may accept higher concentration if contracts are sticky and multi-year.

Use the revenue metric that drives your operating decisions. For subscription businesses, ARR or MRR usually best reflects forward-looking exposure. Recognized revenue can lag contractual reality. If you sell annual prepaid, ARR still captures renewal risk. For usage-based, consider both current run-rate and peak-month exposure.

Don't avoid big customers; manage the downside. Pair large deals with diversification goals: pipeline targets for your next 20 customers, packaging that sells well to mid-market, and clear limits on customer-specific work. Use multi-year terms, renewal notice periods, and expansion clauses to reduce single-customer volatility.

Many will flag top-customer exposure above 15 to 25 percent of ARR, and top-five exposure above 40 to 50 percent, especially if retention is weak or contracts are short. They will ask who can churn, when, and why. Strong net revenue retention and multi-year commitments can offset higher concentration.

Review monthly, and immediately after any large expansion, downgrade, or renewal risk. Triggers include a single customer crossing a set threshold, a top customer entering a renewal window, product usage declining in that account, or increased dependency on bespoke features. Tie triggers to specific actions and owners.