Table of contents

Number of reactivations

Reactivations are the cheapest "new" customers you'll ever get—because you already paid to acquire them once. But the count can also hide a problem: customers who never should have churned in the first place (billing failures, unclear value, bad onboarding) and are now bouncing in and out.

Number of reactivations is the count of previously paying customers who had churned and then became paying customers again during a specific period (usually a week or month).

This article shows how to define it cleanly, calculate it consistently, and use it to make better decisions about retention, billing recovery, and win-back strategy—without fooling yourself with a flattering number.

What counts as a reactivation

Founders get tripped up on this metric because "reactivation" sounds obvious, but it depends on when you recognize churn and what you consider "inactive."

A practical definition most SaaS teams can implement:

- Customer was previously paid.

- Customer churned (no active paid subscription / access ended).

- Customer returns to paid during the measurement period.

That seems simple—until you hit edge cases.

Common edge cases to decide upfront

1) Failed payments and dunning

- If access never ended (you kept them active while retrying payment), a successful retry is not a reactivation.

- If access ended (subscription canceled/expired) and later they pay and resume, that is a reactivation.

This is why reactivations should be read alongside Involuntary Churn.

2) Cancel and resubscribe inside the same month If your finance/revops policy recognizes churn immediately at cancellation, you might count a reactivation a few days later. If you recognize churn at period end, you may not. Pick a rule and stick with it. (Related: /blog/when-should-you-recognize-churn-in-saas/)

3) Downgrade to free If a customer moves from paid to free and later returns to paid:

- Some teams count that as reactivation (because paid relationship ended).

- Others treat it as conversion from free.

The more important point is consistency, and segmentation: keep "paid → free → paid" separate from "paid → churned → paid."

4) Subscription-level vs account-level If an account can have multiple subscriptions, decide whether you measure:

- Account reactivation: the account had zero paid subscriptions and goes back to at least one.

- Subscription reactivation: a specific subscription restarts.

For founder decision-making, account-level is usually more actionable because it maps to customer relationships and win-back motions.

The Founder's perspective

If your team can't answer "Did this customer truly leave?" you'll misallocate time. You'll celebrate a reactivation spike that was actually billing recovery—or you'll miss a real product win-back signal because it's buried in noisy definitions.

How to calculate it consistently

At its core, this is a count of events in a time window.

A clean event-based formula looks like this:

Where \text{I}(\cdot) is an indicator that equals 1 when the condition is true.

Set a "reactivation lookback" window

A customer who churned five years ago and comes back is still a reactivation—but mixing those with last-month churn makes the metric hard to use.

Many teams add a policy like:

- Count reactivations only if the customer churned within the last 12 months, and track older returns separately.

This keeps the metric aligned to win-back programs you can actually influence.

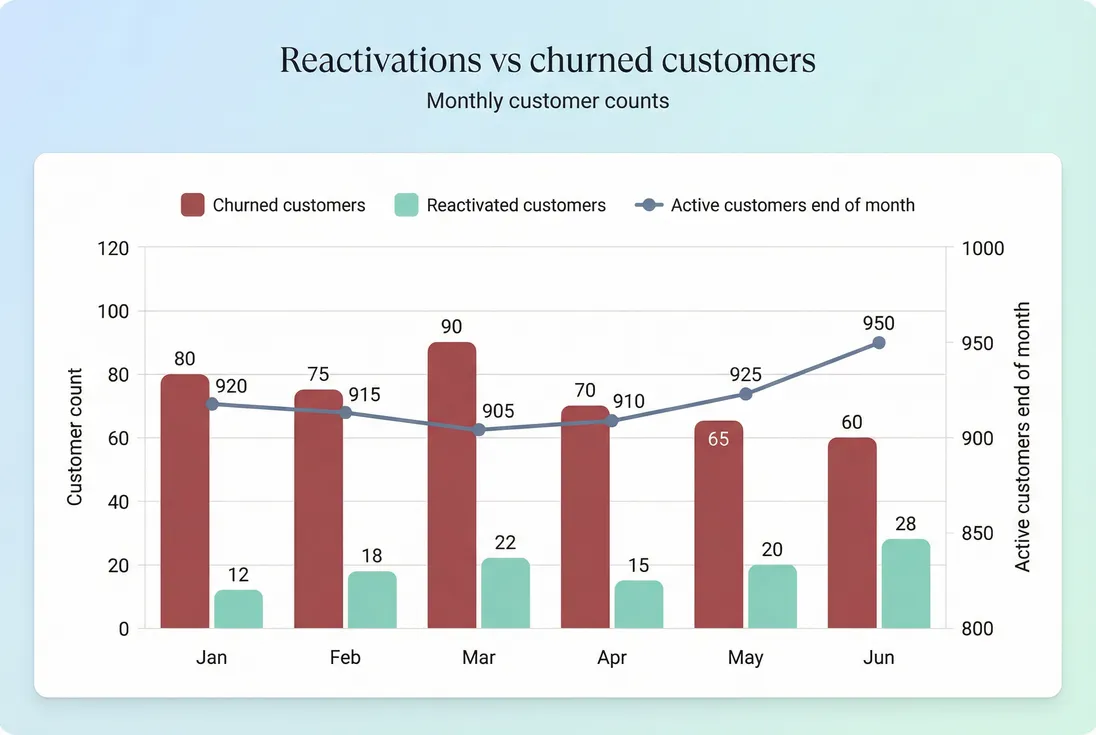

Pair it with metrics that prevent bad conclusions

Number of reactivations is useful, but it is incomplete. Founders should track it with:

- Reactivation MRR: how much revenue came back, not just how many logos

(See Reactivation MRR.) - Logo churn: how many customers left in the first place

(See Logo Churn.) - Time-to-reactivate: how long it takes churned customers to return.

- Reactivation rate (optional): reactivations relative to a base.

One practical rate that stays stable as you grow:

It answers: "Of the customers we lost recently, how many are we getting back?"

What this metric reveals (and what it doesn't)

Founders typically look at reactivations for four reasons.

1) Whether churn is truly permanent

Churn is often treated as irreversible. In reality, some segments churn for reasons that are reversible:

- Budget freeze

- Project ended temporarily

- Champion left

- Seasonal usage

- Billing failure

Reactivations tell you how much churn behaves like a pause rather than a divorce.

This matters for forecasting and for how aggressively you need to replace churn with new acquisition.

2) Whether your win-back motion is working

If you run any win-back efforts (emails, outbound sequences, in-app prompts, targeted offers), reactivations become your simplest scoreboard.

But don't evaluate campaigns on count alone. A discount-heavy win-back can inflate reactivations while harming ASP (Average Selling Price) and ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account). If reactivated customers come back at a much lower price, your "wins" may be dilutive.

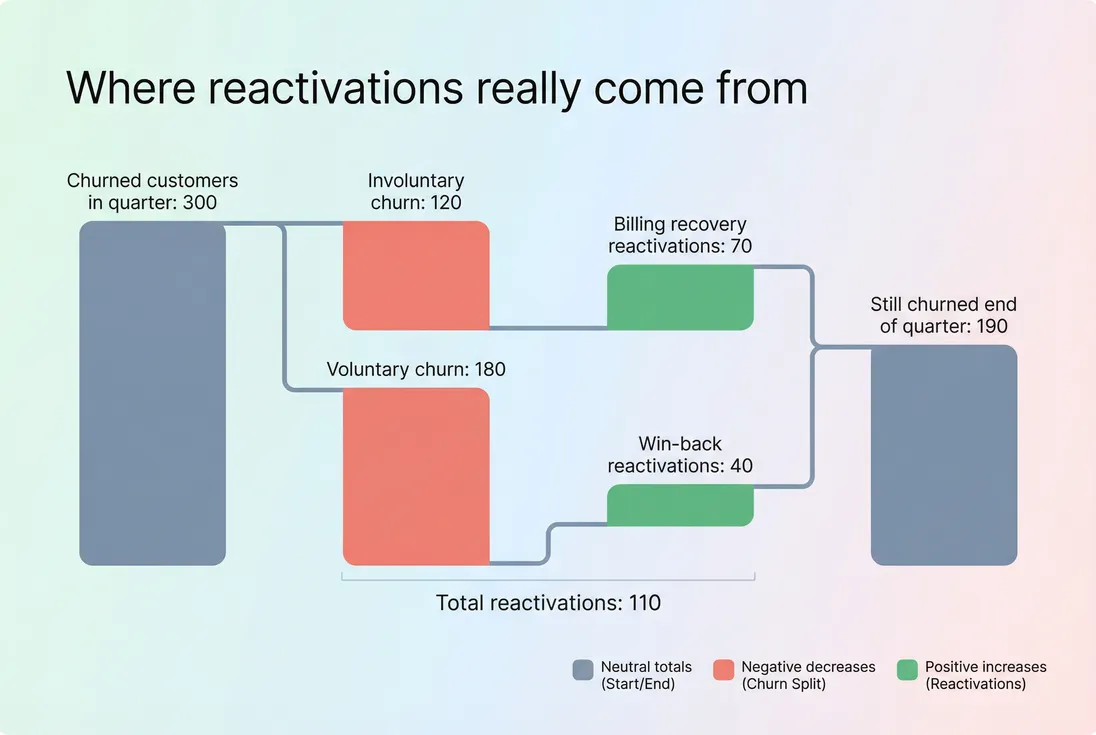

3) Whether you have churn you can prevent

A spike in reactivations dominated by short gaps (days to a couple weeks) often means:

- involuntary churn (cards failing, bank issues), or

- accidental churn (customers didn't realize they canceled), or

- avoidable churn (customers leave due to a temporary setup issue, then come back once fixed)

That's less "win-back excellence" and more "process and product debt."

4) Your best reactivation targets

When you break reactivations down by customer attributes, you learn where win-backs are most likely:

- plan tier

- customer size

- acquisition channel

- tenure before churn

- product usage level (see DAU/MAU Ratio (Stickiness))

- churn reason (see Churn Reason Analysis)

Those segments are where you can spend time and money with confidence.

How to interpret changes without fooling yourself

Reactivations going up feels good, but you need to interpret why they moved.

A diagnostic table founders can use

| Pattern you see | Likely explanation | What to check next | Decision it drives |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reactivations up, churn flat | Win-back improved, or product value improved for a segment | Segment by time-since-churn and plan; compare to Reactivation MRR | Scale win-back motion; expand to similar segments |

| Reactivations up, churn also up | Customer "bounce" cycle, billing issues, or positioning mismatch | Split voluntary vs involuntary; review cancellation reasons | Fix root churn drivers; don't celebrate the recovery |

| Reactivations down, churn down | Healthier product and retention | Validate via NRR (Net Revenue Retention) and GRR (Gross Revenue Retention) | Rebalance effort from win-back to expansion |

| Reactivations down, churn flat | Win-back weakening or market getting tighter | Time-to-reactivate trend, offer performance, competitor losses | Refresh win-back messaging, product gaps, pricing |

| Reactivations spike for 1–2 weeks | Reporting changes or billing recovery event | Payment retry policy changes, card updater changes, recognition rules | Normalize the metric and annotate the change |

The Founder's perspective

I care less about a high reactivation count and more about what's causing it. If it's billing recovery, I'll invest in dunning. If it's genuine win-back, I'll invest in customer marketing and outbound. If it's churn-and-return behavior, I'll fix onboarding and value realization.

When reactivations mislead you

There are two classic ways this metric lies.

1) It can reward bad retention

If customers churn because they don't reach value, and you later convince them to return, your reactivation count rises—but your product still leaks. That usually shows up as weak Customer Churn Rate and poor Retention curves.

If your reactivations are "high," ask:

- How many reactivated customers churn again within 30–90 days?

- Do reactivated customers expand like your healthy base, or do they stay small?

- Is your churn reason mix shifting?

2) It can be inflated by involuntary churn mechanics

A lot of teams unknowingly count billing retries as churn + reactivation, because the subscription briefly flips states.

If you're using a subscription analytics system, make sure your event definitions are stable. In GrowPanel, this is typically something you validate by reviewing MRR movements and applying filters to isolate the underlying events (see MRR movements and Filters).

If "reactivations" are mostly customers returning within a few days, you're probably measuring billing friction—not win-backs.

How founders use number of reactivations

The metric becomes powerful when you tie it to specific decisions.

Build a win-back pipeline you can manage

Treat churned customers as a pipeline with stages:

- Churn event captured (with reason)

- Eligible for win-back (based on segment and time since churn)

- Touched (sequence or outreach)

- Reactivated

- Stabilized (retained for 60–90 days)

"Number of reactivations" is stage 4. But you'll run the business better if you also track stage-to-stage conversion rates.

Practical segmentation that drives action:

- High ARPA accounts (see ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account)) get human outreach.

- Low ARPA/high volume get automated win-back.

- Involuntary churn gets billing recovery first.

Decide between dunning and discounting

If reactivations are mostly short-gap returns and concentrated in failed payments, you'll get more ROI from:

- improving payment retries

- reducing expired-card churn

- tightening your billing notifications

If reactivations are long-gap returns and tied to budget timing or internal change, you may need:

- a lighter re-entry plan

- better onboarding the second time

- packaging that matches "come back small, expand later"

Be careful with blanket discounting. It can lift reactivations while quietly lowering MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue) quality and increasing contraction later (see Contraction MRR). If you do use discounts, formalize it (see Discounts in SaaS) and measure the post-reactivation retention.

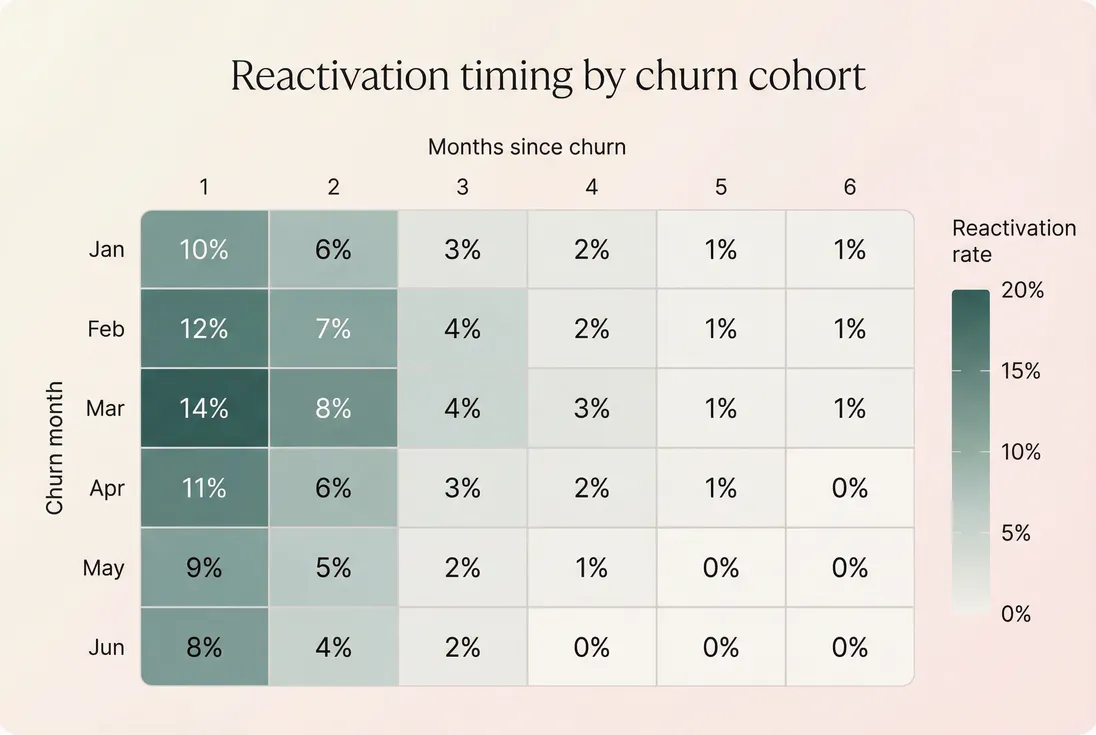

Improve forecasting and capital efficiency

Reactivations can materially change how you think about "net new" customers and how hard you must push acquisition to hit a growth target.

A simple approach:

- Calculate average monthly churned logos.

- Estimate a lagged reactivation curve (e.g., what percent returns in month 1, month 2, month 3).

- Include that in your forward customer count forecast.

This helps you avoid over-hiring in acquisition when a predictable chunk of churn comes back.

That flows into capital efficiency metrics like Burn Multiple and CAC Payback Period because win-backs usually have lower incremental cost than cold acquisition.

Pressure-test product value and onboarding

If reactivations cluster among customers with very short lifetimes, it can indicate:

- they didn't reach first value before churning (see Time to Value (TTV))

- onboarding isn't sticky (see Onboarding Completion Rate)

- usage didn't cement the habit (see Feature Adoption Rate)

In that situation, don't optimize your win-back emails first. Fix the first-time experience so you don't need the win-back.

Practical benchmarks and targets

There isn't a universal "good" number of reactivations because it depends on how many customers churn and how you recognize churn. But founders can set useful internal targets.

Benchmarks that actually help

Instead of chasing an absolute count, track these:

Win-back ratio (reactivations relative to recent churn)

If this steadily improves, your churn is becoming less permanent.Reactivation mix (billing recovery vs win-back)

If most reactivations are billing recovery, invest in reducing involuntary churn first.Quality of reactivations

- Retention of reactivated customers at 60–90 days

- Reactivation MRR per reactivated customer (proxy for returning at healthier plans)

A founder-friendly target: reactivated customers should retain at least as well as newly acquired customers after the first 60–90 days. If they don't, you're buying short-term wins.

Implementation checklist (so your metric is trustworthy)

Before you put this on a board slide, confirm:

- You have a documented rule for when churn is recognized.

- You've separated involuntary vs voluntary churn paths.

- You count unique customers (not invoices), and you know whether it's account-level or subscription-level.

- You can segment reactivations by:

- time since churn

- plan and ARPA band

- churn reason

- You review it alongside:

- Logo Churn

- Reactivation MRR

- Cohort Analysis for longer-term patterns

If you treat number of reactivations as "free growth," you'll miss the point. Used well, it's a management signal: how reversible your churn is, which losses are worth winning back, and whether your biggest retention wins should come from billing fixes, product value, or targeted outreach.

Frequently asked questions

A reactivation is when a previously paying customer who fully churned becomes a paying customer again. The key is the customer had a period with no active paid subscription. Reactivations are not upgrades, downgrades, renewals without a lapse, or monthly billing retries that never ended access.

Not always. Reactivations can reflect successful win-back efforts, but they can also indicate preventable churn, like failed payments or poor onboarding that causes short churn-and-return cycles. Treat the count as a diagnostic signal and break it down by churn type, time since churn, and plan.

Benchmarks vary widely by segment. Many B2B SaaS companies see a meaningful share of churned customers return within 6–12 months, but the more important benchmark is internal: reactivations relative to churn and relative to CAC. Track your win-back ratio and payback versus acquisition.

Reactivations are a leading indicator for near-term revenue recovery, especially if you pair them with Reactivation MRR. Model reactivations as a percentage of prior churned logos and apply a typical time-to-reactivate curve. This improves forecasts versus assuming churn is permanently lost.

First, rule out billing noise: dunning improvements, card updater changes, or reporting definition changes can inflate reactivations. Then segment by involuntary versus voluntary churn and by time since churn. A spike dominated by quick returns often points to payment failures or cancellation friction, not true win-backs.