Table of contents

New Acquisitions

New acquisitions is the fastest way to tell whether your growth engine is actually producing new customers—or whether you're just reshuffling the same base through churn and reactivation. If this number stalls, you eventually feel it everywhere: pipeline stress, revenue plateaus, team morale, and tougher fundraising conversations.

In plain English: new acquisitions is the count of brand new paying customers you add during a period (usually a week or month), excluding returning customers.

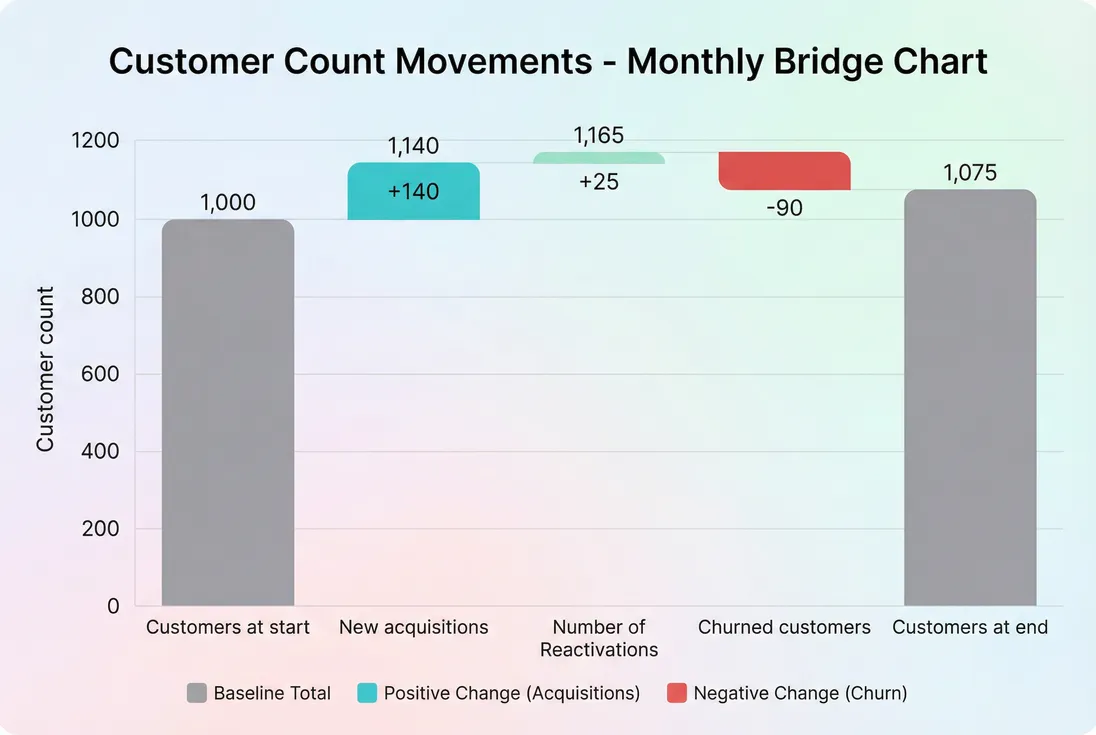

A customer-count bridge makes it obvious whether new acquisitions is truly driving growth or merely offsetting churn.

What counts as a new acquisition

Founders get tripped up here because "new" can mean three different things depending on your data and motion.

The recommended definition (most SaaS)

Count a customer as a new acquisition when:

- They have no prior paid history (no prior active or canceled paid subscription), and

- They begin a paid recurring relationship in the period.

That aligns best with how you'll analyze MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue), retention, and payback.

What should not count

- Trials and signups. Those belong in Signups Count and trial analytics (see Free Trial).

- Returning customers. Those belong in Number of Reactivations (and often show up as Reactivation MRR).

- Upgrades/seat adds from existing customers. That's expansion (see Expansion MRR).

- One-time purchases. Exclude unless they create a recurring subscription (see One Time Payments).

The Founder's perspective: If you can't separate new acquisitions from reactivations and upsells, you'll misdiagnose growth. You'll "celebrate" a good month, hire ahead of demand, then discover you didn't actually add new logos—your base just expanded temporarily or came back after churning.

The two views you should keep side by side

Most teams track new acquisitions in two parallel ways:

- New customers (count): how many logos you added.

- New customer MRR: the economic weight of those logos.

A month with 200 new customers at $50 ARPA is not the same as 20 new customers at $500 ARPA. Pair this metric with ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account) and ASP (Average Selling Price) to keep the story honest.

How to calculate it

You can calculate new acquisitions cleanly with billing data alone, but you must be explicit about timing and identity.

Basic calculation

For each customer, identify their first paid start date (or first successful recurring invoice date, depending on your policy). Count customers whose first paid start date falls inside the period.

If you want a rate (helpful for comparing different stages), normalize by starting customers:

This is especially useful when your base is growing quickly. "We added 80 customers" is hard to interpret; "we added 8% of starting customers" is much more comparable over time.

Net customer change (why founders care)

New acquisitions is only one component of whether your customer base grows.

To interpret net growth correctly, you need churn context (see Customer Churn Rate and Logo Churn).

Timing rules that prevent bad decisions

Pick a rule, document it, and stick to it:

- Count on contract start / subscription activation if you're sales-led and contracts are signed before billing.

- Count on first successful payment if you're self-serve and want the cleanest "cash-backed" definition.

- Be consistent with annual plans. Count them as a new acquisition when the subscription begins, then use ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue) or normalized MRR to avoid overstating monthly momentum.

If you also track finance metrics like Deferred Revenue or Recognized Revenue, keep them separate from the acquisition count. The count is about customer movement, not accounting treatment.

If you use GrowPanel

Use MRR movements to separate new business from expansion and reactivation, and use Filters to slice by plan, country, or source tags you pass through billing metadata.

What changes usually mean

New acquisitions moves for identifiable operational reasons. When it changes, you should immediately ask: is it demand, conversion, capacity, or measurement?

If new acquisitions rises

Common "good" drivers:

- Higher lead volume (see Lead Velocity Rate (LVR))

- Better conversion from lead to customer (see Lead-to-Customer Rate and Conversion Rate)

- Shorter sales cycles (see Sales Cycle Length)

- Better activation/onboarding (see Onboarding Completion Rate)

Common "risky" drivers:

- Heavy discounting (see Discounts in SaaS)

- Looser qualification to hit a quota

- A channel change that brings low-intent buyers

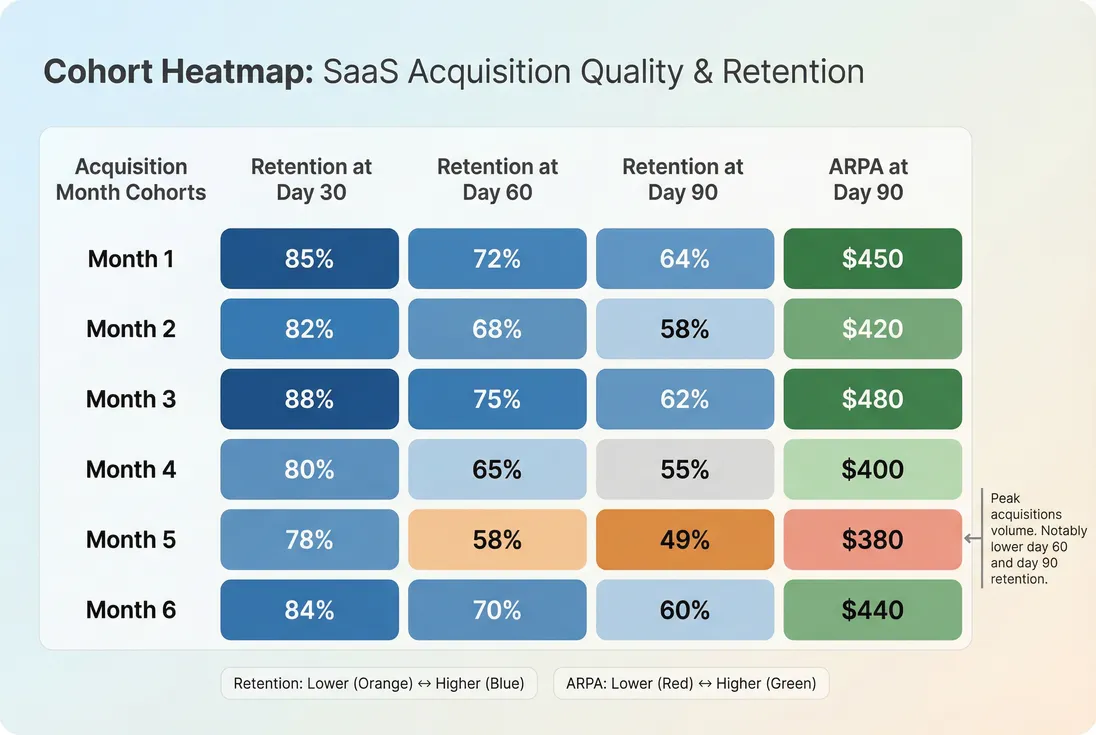

A simple quality check: when new acquisitions rises, new customer MRR and early retention should not fall. If they do, you're buying growth with future churn.

If new acquisitions falls

Common causes:

- Pipeline dried up (see Qualified Pipeline)

- Win rate deteriorated (see Win Rate)

- Pricing/packaging created friction (see Per-Seat Pricing and Price Elasticity)

- Product issues slowed activation or increased early churn (connect to Time to Value (TTV))

Operationally, a sustained decline is usually one of two things:

- Top-of-funnel issue (not enough qualified opportunities), or

- Down-funnel issue (same volume, worse conversion).

The fix depends on which, so don't jump straight to "spend more."

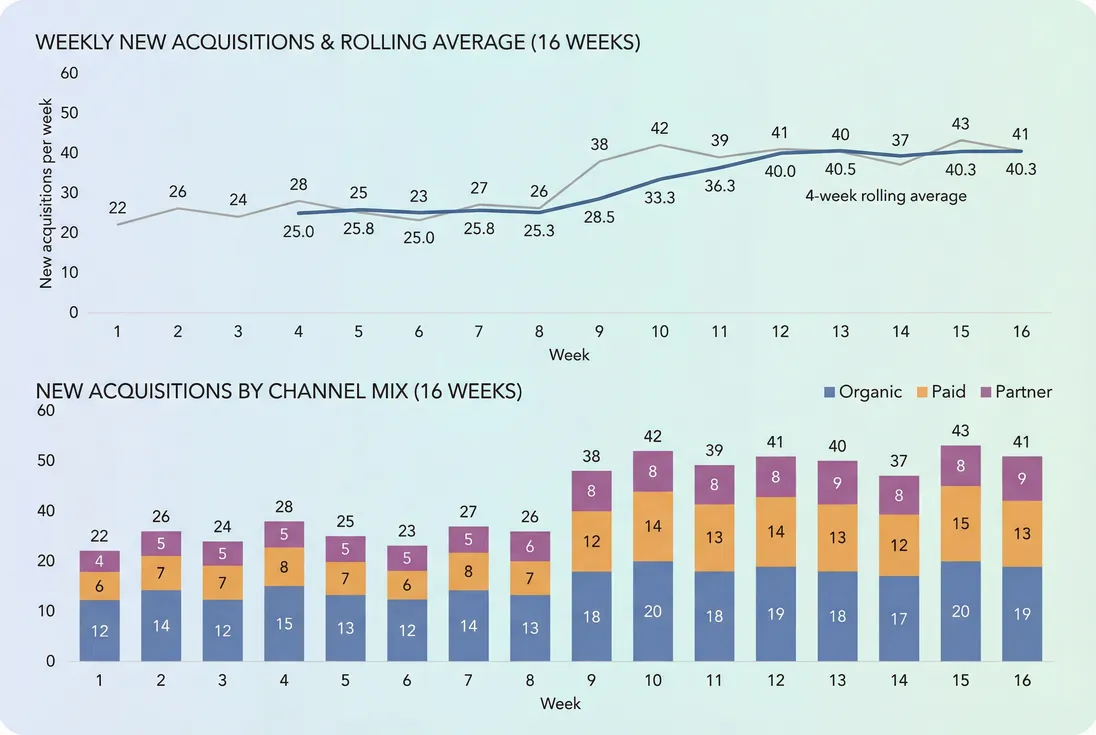

When acquisitions change, separate volume from mix: a channel-driven spike can look great until retention and payback catch up.

A practical benchmark framing (without false precision)

Instead of chasing generic benchmarks, anchor new acquisitions to three realities:

- Churn replacement: are you acquiring more customers than you lose?

- Onboarding capacity: can your team successfully activate what you sell?

- Payback economics: does growth improve or worsen CAC Payback Period?

A simple way to set an internal "healthy range" is:

- Minimum viable: new acquisitions consistently exceed churned customers.

- Healthy growth: new acquisitions exceed churned customers and early cohorts retain well (see Cohort Analysis).

- Scalable growth: the above holds while CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost) and payback remain stable.

How founders use it

New acquisitions becomes powerful when it's tied to decisions: spend, hiring, and positioning.

1) Decide where to allocate go-to-market spend

New acquisitions is a volume output. To make it actionable, pair it with spend and quality:

- Spend efficiency: CAC (and trend)

- Speed: Sales Cycle Length

- Quality: retention and expansion (see NRR (Net Revenue Retention) and Expansion MRR)

If you're tracking Burn Multiple, new acquisitions helps explain why the multiple is improving or degrading: are you generating more customers at the same spend, or just booking larger deals?

The Founder's perspective: When new acquisitions is flat but spend rises, you're not "investing in growth"—you're paying more for the same output. That's when you pause channel scaling, tighten qualification, and focus on conversion and activation before adding budget.

2) Plan hiring and onboarding capacity

A classic early-stage failure mode: you improve acquisition, then churn spikes because onboarding and support can't keep up.

Use new acquisitions to capacity plan:

- Customer success staffing and onboarding throughput

- Support workload (tickets scale with new customers, not just revenue)

- Implementation bandwidth (especially for higher-touch plans)

A simple operational rule: if you expect acquisitions to jump 50% next month, you should already have the onboarding path and staffing ready this month.

3) Keep pricing and discounting honest

Discounts can inflate new acquisitions while damaging long-term economics.

Watch for these patterns:

- New acquisitions up, ARPA down (see ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account))

- New acquisitions up, logo churn up within 30–90 days (see Logo Churn)

- New acquisitions up, but new MRR flat (see MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue))

This often indicates you're pulling in customers who are price-sensitive or not fully qualified.

4) Detect whether growth is "new" or "recovered"

If your story is "we're growing," investors and operators will ask: how much is truly new?

Break your growth narrative into:

- New acquisitions (new logos)

- Number of Reactivations (win-backs)

- Expansion (same logos paying more)

All three can be good. They just imply different strategic priorities (brand/pipeline vs retention vs product monetization).

Where teams mis-measure it

Measurement issues don't just create bad dashboards; they cause expensive operational mistakes (hiring ahead, overspending, misreading PMF).

Duplicate and merged accounts

If one company appears as multiple customer records (common in self-serve + sales-assist hybrids), you'll overcount acquisitions.

Fixes:

- Normalize domains and billing identities

- Create a consistent "account" concept in your CRM/billing sync

- Audit top "new" accounts monthly for duplicates

Free-to-paid transitions treated inconsistently

If you offer freemium, decide whether "new acquisition" is:

- First time they become paying (recommended), or

- First time they sign up (not recommended for this metric)

Freemium signups belong in Freemium Model analysis, not new acquisitions.

Refunds, chargebacks, and involuntary churn noise

A customer who pays and refunds quickly: do you count them as acquired?

Operationally, they did convert, but they weren't retained. The clean approach:

- Count them as a new acquisition when they first pay

- Then let churn/refund metrics tell the truth afterward (see Refunds in SaaS and Chargebacks in SaaS)

- Track early churn separately so you can see if "acquisitions" are sticking

Reactivations misclassified as new

This is one of the most common issues when you change billing systems or identifiers. If your "new acquisitions" jumps after a migration, assume it's a classification bug until proven otherwise.

A quick test: compare new acquisitions with reactivation volume and look for impossible shifts (e.g., reactivations drop to near zero while new acquisitions spikes).

Volume is not the goal—durable cohorts are. A cohort view reveals when acquisition growth is actually low-quality churn in disguise.

A simple operating checklist

Use this monthly to turn "new acquisitions" from a number into action:

- Validate the definition: exclude Number of Reactivations, exclude expansion.

- Review mix: acquisitions by plan, segment, and channel (use consistent tags).

- Tie to economics: trend CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost) and CAC Payback Period alongside acquisitions.

- Check early durability: day 30/60/90 retention by acquisition cohort (see Cohort Analysis).

- Capacity reality check: can onboarding/support absorb next month's target?

The Founder's perspective: The right target is rarely "more new customers." It's "more of the right customers, acquired predictably, with retention strong enough that growth compounds." New acquisitions is the lead indicator—cohort retention is the proof.

Frequently asked questions

New acquisitions counts customers who become paying customers for the first time in a period. Signups and trials are top of funnel activity, not revenue. If you optimize signups without improving conversion, you can look busy while growth stalls. Track both, but don't confuse them.

Track both. Customer count tells you if your go to market motion is producing enough new logos to offset churn. New customer MRR tells you if those customers are meaningful economically. When count rises but new MRR is flat, you're often attracting smaller accounts or discounting heavily.

There is no universal benchmark because it depends on ACV, sales cycle length, and market size. A practical approach is to compare new acquisitions to churned customers and to your capacity to onboard. If new customers are not comfortably exceeding churn, growth will feel fragile.

Spikes are often driven by a new channel, a promotion, or looser qualification. If onboarding and customer success capacity doesn't scale, early churn rises. Validate acquisition quality with cohort retention and early expansion, not just the first invoice. Volume without durability increases support load and reduces capital efficiency.

Reactivations are returning customers and should not be counted as new acquisitions, because they reflect retention and win back performance. Annual plans should count as a new acquisition at the contract start date, but revenue timing should be handled via ARR or normalized MRR so you don't overstate monthly momentum.