Table of contents

Metered revenue

Founders care about metered revenue because it's often where "growth" quietly turns into volatility: one big customer ships a feature, usage spikes, your top-line jumps—then finance asks why next month looks flat. If you can't explain metered revenue in drivers (customers × usage × price), you can't forecast, price, or staff confidently.

Metered revenue is the portion of revenue generated from measured customer usage during a period—API calls, events, seats over a limit, storage, minutes, credits consumed—multiplied by the applicable unit price (and adjusted for free allowances, credits, and discounts).

It typically shows up as usage charges, overages, or consumption fees in a Usage-Based Pricing model, often alongside a subscription base.

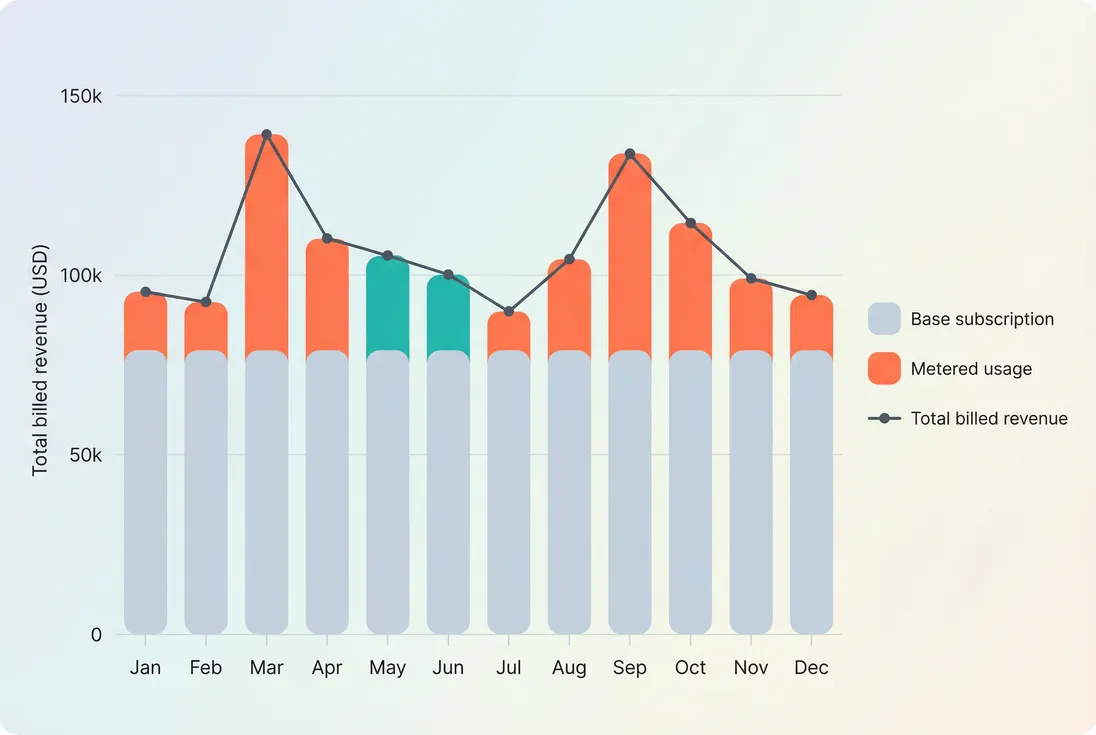

Separating base subscription from metered usage prevents you from mistaking volatility for sustainable growth—and makes forecasting conversations much more concrete.

What metered revenue reveals

Metered revenue is a behavioral revenue metric. It's less about what customers agreed to pay and more about what they actually did.

When you track it cleanly, it answers founder-level questions like:

- Is product adoption deepening (more usage per account), or are we just adding logos?

- Are customers hitting limits that justify packaging changes?

- Are we taking on customer concentration risk through a few heavy consumers?

- Are we funding high variable costs with sufficiently high unit economics?

This is why metered revenue pairs naturally with:

- ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account) (are accounts spending more because they're growing, or because pricing changed?)

- Net Revenue Retention (are existing customers expanding via usage?)

- Customer Concentration Risk (is growth dependent on one whale's consumption?)

The Founder's perspective

If your metered revenue rises but your customer count doesn't, you're getting an expansion signal. That can justify investing in reliability, scale, and enterprise support. If it rises because one customer doubled usage, you may need contract commitments and tighter billing governance before you hire ahead of demand.

How to calculate it (without accounting debates)

At its simplest, metered revenue for a period is billable usage multiplied by the effective unit price.

The tricky part is defining billable units in a way that matches invoices.

Most SaaS usage models include one or more of the following:

- Included allowance (X units included per month)

- Free tier or trial usage

- Prepaid credits (consume credits before charging)

- Tiered unit pricing (unit price changes at volume thresholds)

- Minimum commits (pay at least $Y regardless of usage)

A practical way to express billable units:

A concrete example

Assume a customer is priced as:

- $500/month base subscription

- 1,000 included events

- $0.02 per event overage

- They used 2,500 events this month

- No credits

Then:

- Billable units = 2,500 − 1,000 = 1,500

- Metered revenue = 1,500 × $0.02 = $30

- Total billed = $530

That $30 is small. But when you have hundreds of customers—or a handful with millions of events—metered revenue becomes a major growth driver (and a major source of noise).

Don't mix these three "revenues"

Founders get burned when different teams use "revenue" to mean different things:

| Concept | What it reflects | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|

| Metered revenue (operational) | Usage-driven charges for a period | Pricing, adoption, forecasting drivers |

| Billed revenue (invoice) | What you invoiced customers | Cash planning, collections, disputes |

| Recognized revenue (accounting) | What's recognized under your policy | Financial statements, audits |

If you're doing commits or annual prepayments, you'll also care about Deferred Revenue and Recognized Revenue. If collections lag, tie it to Accounts Receivable (AR) Aging.

What makes it go up or down

Metered revenue moves for only a few fundamental reasons. Your job is to decompose changes into those drivers fast, so decisions don't become arguments.

The three driver model

A founder-friendly driver model looks like this:

Where "effective unit price" already incorporates tiering, discounts, credits, and negotiated rates.

In practice, most surprises come from one of these buckets:

More active accounts

More customers reaching the point of generating usage charges (often a product activation story).Higher usage intensity

Existing customers consuming more (often value realization, growth in their business, or feature adoption).Higher effective unit price

Packaging changes, overage pricing updates, discount roll-offs, or customers moving into higher-priced tiers.

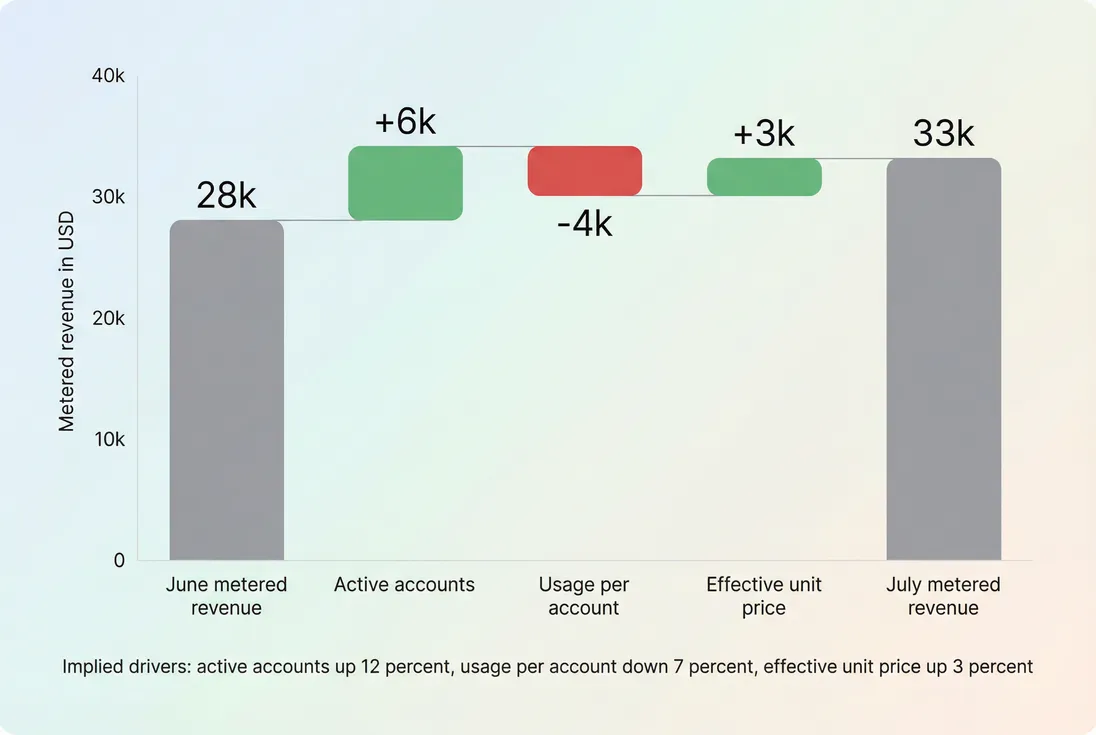

A decomposition you can show your team

A simple bridge chart turns a confusing usage swing into three explainable levers: how many accounts generated usage, how much they used, and what you charged per unit.

The Founder's perspective

When metered revenue is down, don't let the org default to "customers are churning." First ask: did they use less, did we charge less, or did billing fail to capture usage? Each implies a different action—product, pricing, or revenue operations.

Common real-world causes (and what they imply)

1) Seasonality and workflow changes

Example: analytics, payroll, tax, education, and retail products often have predictable peaks.

- What to do: forecast with seasonality bands; don't staff scale-up from peak-month metered revenue alone.

- Pair with: Burn Rate so hiring doesn't outrun normalized demand.

2) Product improvements that reduce usage

If you optimize API calls or compress storage, customers might consume fewer units while still getting more value.

- Good outcome: customers happier, costs lower.

- Bad outcome: pricing no longer maps to value; you may need to re-anchor packaging.

3) Customers hitting limits

Usage rising because customers hit included caps or thresholds.

- Opportunity: convert "pain" into expansion—add a higher base plan, commits, or better tiering.

- Risk: customer surprise invoices drive involuntary churn or disputes (see Involuntary Churn).

4) Discounting and credits

Credits can mask growth in measured usage while metered revenue stays flat.

- Track usage and credits separately.

- Read up on how concessions distort trend lines in Discounts in SaaS.

5) Instrumentation or rating failures

Dropped events, late pipelines, incorrect customer mapping, or pricing tables out of date.

- Symptom: usage in product analytics doesn't match invoices.

- Fix: build a daily reconciliation between measured units, billable units, and invoice line items.

Where founders misinterpret metered revenue

Mistake 1: Treating it like MRR

Metered revenue is not "recurring" in the way MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue) is designed to be. You can have a great business with volatile metered revenue—but you should not run subscription-style planning assumptions on it.

Use MRR for:

- baseline growth,

- retention,

- pricing changes to base plans,

- board-level predictability.

Use metered revenue for:

- adoption depth,

- capacity planning,

- value-based pricing validation,

- identifying upsell moments tied to usage.

If you do want a more commitment-oriented view, compare your metered stream to CMRR (Committed Monthly Recurring Revenue) concepts (commits, minimums, contracts) so planning isn't held hostage by spikes.

Mistake 2: Ignoring unit economics

Metered models often come with variable costs: compute, storage, third-party APIs, or data egress.

A surge in metered revenue can be great—or it can be margin-neutral if COGS rises in lockstep.

Tie usage growth to:

- COGS (Cost of Goods Sold)

- Gross Margin

- your internal cost per unit (even a rough estimate)

If your cost per unit is $0.015 and you charge $0.02, you don't have a pricing problem—you have a strategy problem.

Mistake 3: Blending billing timing into trend analysis

Usage is measured continuously, but billing can be:

- in arrears (bill next month for last month's usage),

- on different cutoffs by customer,

- subject to minimums and true-ups.

If you're analyzing "July metered revenue" based on invoices sent in July, you might be looking at June usage. That's fine—just label it correctly and keep definitions consistent.

Also account for:

- Refunds in SaaS (reversals change the period story)

- VAT handling for SaaS (tax should not inflate your unit economics analysis)

How founders use it for decisions

1) Pricing and packaging decisions

Metered revenue is your feedback loop for whether pricing matches value.

Signals to watch:

- Many customers consistently hovering just under the included allowance

→ allowance might be too generous or too "gameable." - Many customers spiking into overages unexpectedly

→ add in-product alerts, caps, or clearer packaging to reduce surprise. - A few customers accounting for most metered revenue

→ consider enterprise commits, custom contracts, or dedicated SKUs.

A practical packaging ladder many founders converge on:

| Customer stage | Pricing pattern | Why it works |

|---|---|---|

| New / small | Base + generous included units | Reduces friction and surprise |

| Growing | Base + predictable overage | Lets revenue scale with usage |

| Large / enterprise | Commit + discounted overage | Reduces volatility and improves planning |

If you sell annuals, this interacts with ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue) reporting too: commits can be "ARR-like," while true variable overages will not behave like ARR.

2) Forecasting and capacity planning

Because metered revenue is driven by behavior, forecasting it from topline history alone is fragile. A more reliable approach:

- Forecast active accounts (from your retention and sales outlook)

- Forecast usage per active account (trend + seasonality + product changes)

- Forecast effective unit price (tier mix, discount policy, negotiated rates)

- Apply concentration guardrails (top 1–5 customers scenarios)

If your board asks for confidence, show ranges:

- Base case (normalized usage)

- High case (a few large customers ramp)

- Low case (seasonal dip + credit-heavy period)

The Founder's perspective

Your best forecasting asset isn't a fancy model—it's a clean explanation of drivers. If you can say "active accounts up 10%, usage per account down 5%, price flat," the team can debate reality. If you can only say "metered revenue is down," people debate opinions.

3) Retention and expansion detection

Metered revenue can act like an early warning system—often earlier than churn shows up.

- Usage down for multiple weeks can precede churn. Pair with Churn Reason Analysis to distinguish "seasonal lull" from "lost value."

- Usage up sharply can precede expansion conversations or justify proactive customer success outreach.

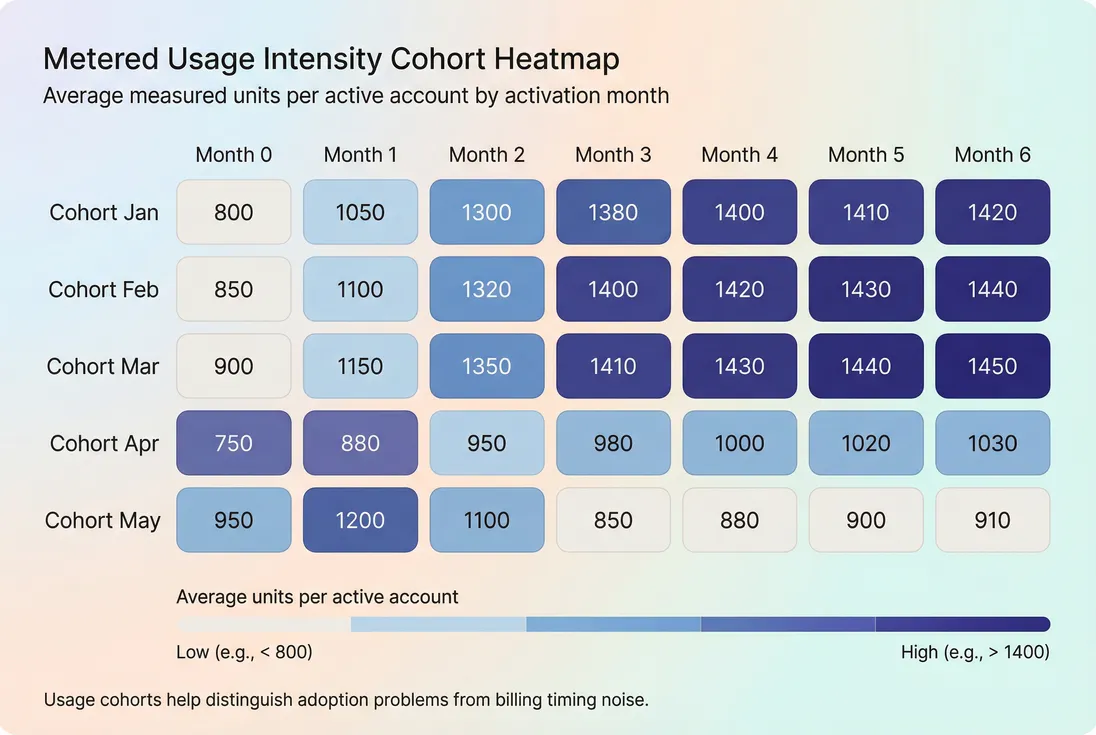

This is where segmentation matters:

- by plan,

- by industry,

- by integration type,

- by cohort.

A cohort view helps separate "new customers ramping" from "old customers plateauing."

Cohort heatmaps make metered revenue actionable: you can see whether newer customers ramp into meaningful usage—or stall before they ever generate expansion.

For deeper cohort methodology, see Cohort Analysis.

4) Sales strategy and deal structure

Sales teams love usage-based pricing because it lowers initial friction. Finance teams hate it because it increases uncertainty. Metered revenue sits in the middle.

Founders can align incentives by structuring deals with:

- a base subscription that covers success costs,

- a minimum commit aligned to expected usage,

- overages priced to preserve margin,

- clear renewal and true-up language.

Then you can measure sales outcomes more cleanly through:

- ASP (Average Selling Price) for base plans

- expansion signals through usage (and later, MRR expansion when customers move tiers)

When the metric "breaks"

Metered revenue becomes misleading when measurement and monetization drift apart. Watch for these failure modes:

Usage attribution errors

Usage events not tied to the right account, workspace, or contract.Rating table drift

Pricing changes not reflected in billing logic (or multiple price books exist).Credit leakage

Credits applied inconsistently, or customer success granting credits without visibility.Invoice aggregation

Usage consolidated across sub-accounts, hiding which customers are growing (or failing).Disputes and chargebacks

A spike in billed metered revenue followed by reversals. Track disputes explicitly; see Chargebacks in SaaS.

A simple control that pays off: every month, reconcile three numbers:

- measured units (from your usage ledger),

- billable units (after allowances and credits),

- invoiced usage charges (from billing).

If any gap is unexplained, treat it like a revenue leak, not a "data problem."

Practical benchmarks and sanity checks

Metered revenue varies wildly by category, so absolute "good" numbers are rare. Instead, use these sanity checks:

- Volatility check: If metered revenue swings ±30% month-to-month, plan with ranges, not point estimates. Consider commits to stabilize.

- Concentration check: If the top 5 customers generate most usage charges, treat it as a strategic risk and align with Customer Concentration Risk.

- Margin check: If variable costs scale nearly linearly with usage, unit price must maintain healthy contribution margin. Otherwise growth can worsen cash burn.

- Behavior check: If product usage is up but metered revenue is flat, investigate credits, discounting, or pricing thresholds.

- Collections check: If metered invoices age worse than subscription invoices, you may have a "surprise bill" problem; connect to Accounts Receivable (AR) Aging.

How to pair it with your core SaaS dashboards

Most founders run the business on recurring metrics like MRR, churn, and retention, then use metered revenue as a "behavior layer."

A practical operating cadence:

- Weekly: usage drivers (active accounts, usage per account), top account movers

- Monthly: metered revenue bridge (drivers), disputes/credits review

- Quarterly: packaging and price review tied to usage distribution

If you're using GrowPanel, keep your subscription foundation clean with MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue), then use MRR movements and retention views to avoid confusing base subscription expansion with usage-driven noise. The goal is a stable baseline plus an explainable variable layer.

Summary: what to do next

- Define metered revenue consistently (measured vs billable vs invoiced).

- Decompose monthly changes into active accounts, usage intensity, and effective unit price.

- Tie it to margin and concentration risk—not just topline growth.

- Use cohorts to see whether customers ramp into meaningful usage.

- Consider commits or packaging changes if volatility blocks planning.

Frequently asked questions

Metered revenue is usage-driven and can swing with customer activity, seasonality, and product adoption. MRR is designed to represent predictable, recurring subscription value. If you mix them, you can misread volatility as growth. Track them separately, then analyze how usage contributes to expansion and retention.

There is no universal benchmark, but founders should optimize for controllable volatility. If metered is small, it may not justify operational complexity. If it is large, forecasting and billing accuracy become strategic. Many successful usage-based businesses aim to pair a stable base commitment with variable overages to reduce surprises.

Forecast from drivers, not from last month's bill. Start with active accounts, expected usage per account, and effective price per unit, then explicitly model known seasonality and credit consumption. Add guardrails for concentration risk and product changes. Reconcile forecasts to invoiced and recognized revenue to catch leakage early.

The most common causes are reduced product usage (customer value drop), plan changes that increase included units, new credits or discounts, instrumentation or ingestion gaps in usage tracking, or billing timing shifts. Triage by decomposing changes into active accounts, usage intensity, and effective unit price before assuming churn.

Separate measured usage from billable usage. Credits and goodwill adjustments reduce billable units or effective price; refunds reverse prior billing; disputes affect cash collection timing. Track all three so you can answer: did customers consume less, did we charge less, or did we fail to collect. This prevents product teams from owning finance problems.