Table of contents

LTV:CAC ratio

Founders care about LTV:CAC because it answers one brutal question: are you buying revenue at a profit, or renting growth at a loss. When this ratio is strong and stable, you can scale confidently. When it's weak—or artificially inflated—you'll feel it later as stalled growth, cash crunches, and messy "we grew but didn't get healthier" board conversations.

Definition (plain English): LTV:CAC is the value you expect to earn from a customer over their lifetime, divided by what it costs you to acquire that customer.

If the ratio is 3, you expect to earn roughly three dollars of lifetime value for every one dollar you spend acquiring customers.

What the ratio reveals

LTV:CAC is a unit economics lens: it compresses your pricing, retention, expansion, gross margin, and go-to-market efficiency into one number. Used correctly, it tells you whether scaling sales and marketing will compound value or compound losses.

Here's what it's good at:

- Comparing go-to-market motions: PLG/self-serve vs sales-led, inbound vs outbound, partners vs paid search.

- Prioritizing fixes: If the ratio is low, you can usually identify whether the problem is CAC (conversion/efficiency) or LTV (retention/expansion/pricing).

- Setting growth constraints: It helps answer, "How hard can we press the gas without destroying unit economics?"

Here's what it's not good at (by itself):

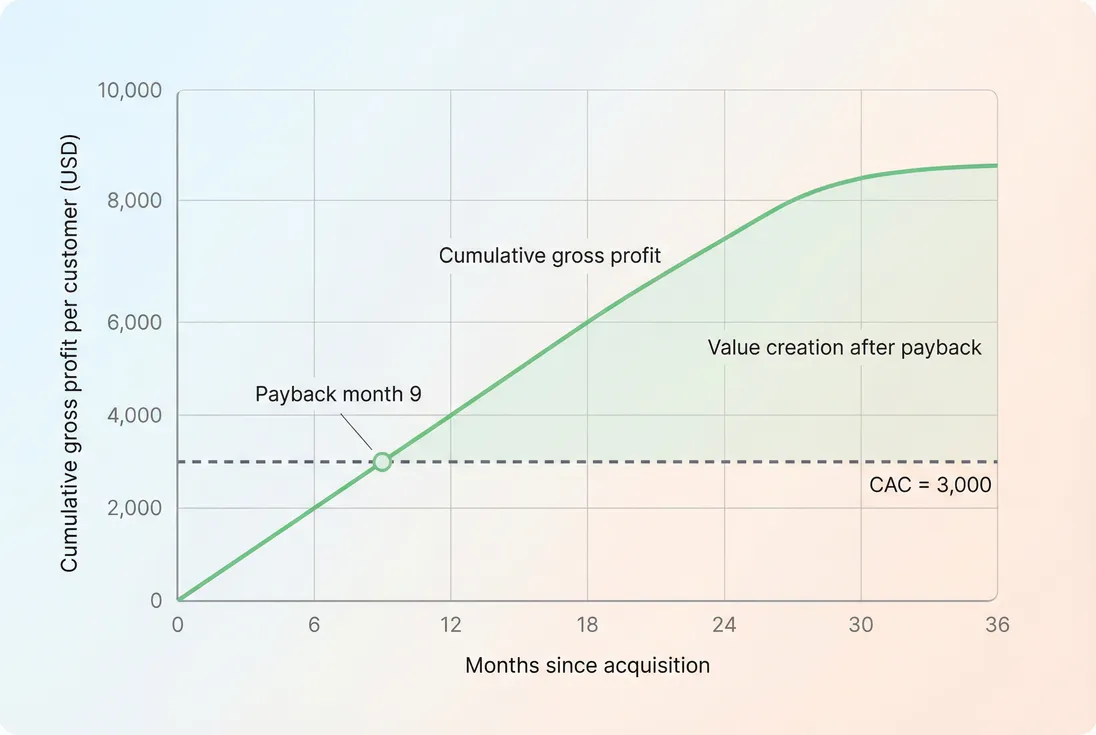

- Cash timing. A great ratio with a 24-month payback can still kill your runway. Pair it with CAC Payback Period.

- Detecting fragility. A ratio can look strong if a few large customers dominate results. Segment and sanity-check with retention and concentration metrics.

The Founder's perspective: If LTV:CAC is improving, you can justify scaling spend if payback is tolerable. If it's worsening, treat growth as a controlled experiment: cap spend, isolate channels, and fix retention or conversion before you "scale the leak."

How to calculate it without fooling yourself

You'll see dozens of LTV and CAC definitions in the wild. The "right" one is the one that matches your decision. For most founders, the goal is: expected lifetime gross profit from a customer divided by fully loaded acquisition cost.

Step 1: calculate CAC

The simplest CAC definition:

Practical guidance:

- Use fully loaded sales and marketing costs (payroll, commissions, paid media, tools, agencies, events, allocated overhead if meaningful).

- Match the denominator to how you sell. If you sell to "accounts," use new accounts. If you sell to "customers" but each account has many workspaces, define it consistently.

- Be careful with time alignment. CAC spend in January may create customers in March. For cleaner analysis, many teams use a trailing average for CAC inputs and cohort-based customer counts.

If you're sales-led, you'll also want CAC by segment (SMB vs mid-market vs enterprise) because blended CAC is rarely actionable.

Step 2: calculate LTV (use gross profit LTV)

A common steady-state approximation is:

Where customer lifetime is often approximated by churn:

So you'll often see:

To understand the components, it helps to link each one to an operational lever:

- ARPA → pricing, packaging, sales execution (see ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account), ASP (Average Selling Price), and Discounts in SaaS)

- Gross margin → infra costs, support load, professional services burden (see Gross Margin and COGS (Cost of Goods Sold))

- Churn / retention / expansion → product value, onboarding, customer success, segmentation (see Customer Churn Rate, Logo Churn, and NRR (Net Revenue Retention))

Important caveat: the churn-based formula assumes a reasonably stable business. If you're early-stage, cohorts are improving, pricing is changing, or you have annual contracts with renewal dynamics, use cohort analysis rather than a single churn rate (see Cohort Analysis).

If you use GrowPanel, your most reliable starting point for LTV inputs is the LTV and retention views, segmented with filters and checked via cohorts (see LTV and Cohorts).

Step 3: compute the ratio

Once LTV and CAC are consistent (same customer unit, similar time frame, LTV in gross profit), compute:

A concrete example (with realistic tradeoffs)

Assume:

- ARPA = $200 per month

- Gross margin = 80%

- Monthly logo churn = 2.5%

- Fully loaded CAC = $3,000

Then:

- Customer lifetime ≈ 1 / 0.025 = 40 months

- LTV ≈ 200 × 0.80 × 40 = $6,400

- LTV:CAC ≈ 6,400 / 3,000 = 2.1

That's not "terrible," but it's not a scale signal unless payback is short and churn is trending down.

The Founder's perspective: Don't debate whether 2.1 is "good." Decide what you'll do at 2.1. Usually: stop scaling paid acquisition, tighten ICP targeting, and invest in activation/onboarding until retention lifts—because improving churn moves LTV far more than shaving small amounts off CAC.

What a good ratio looks like

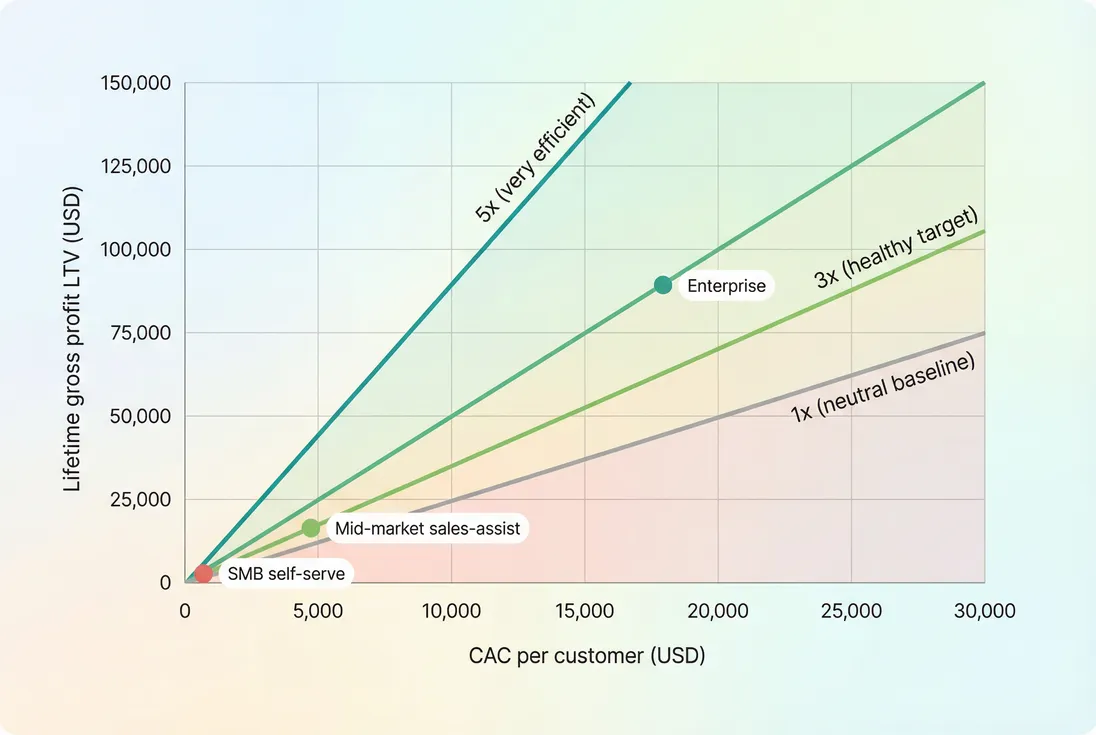

Benchmarks vary by segment and motion. A self-serve product with low ACV can survive with a lower ratio if payback is very fast and retention is strong. Enterprise often targets higher ratios because CAC is higher, sales cycles are longer, and customers demand more support.

Here's a practical benchmark table many founders use as a starting point:

| Context | LTV:CAC < 1 | 1 to 2 | 2 to 3 | 3 to 5 | > 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early-stage (still finding ICP) | Stop and diagnose | Caution | Improving | Strong | Possibly underinvesting |

| SMB self-serve | Unsustainable | Tight | OK if payback fast | Healthy | Likely room to grow faster |

| Mid-market sales-assist | Unsustainable | Weak | Borderline | Healthy | Under-spending or exceptional motion |

| Enterprise sales-led | Usually broken | Weak | Often too low | Healthy | Could still be okay if payback slow |

Two founder-relevant nuances:

- Payback changes the acceptable range. If you recover CAC in 3–6 months, a 2.5 ratio might be fine. If payback is 18+ months, even a 4 ratio can be risky for cash.

- Stability matters more than a single number. A ratio of 4 that's falling each quarter is not "good." It's a warning.

For a second opinion on efficiency, it can help to triangulate with SaaS Magic Number and Burn Multiple. They won't replace LTV:CAC, but they'll expose timing and accounting distortions.

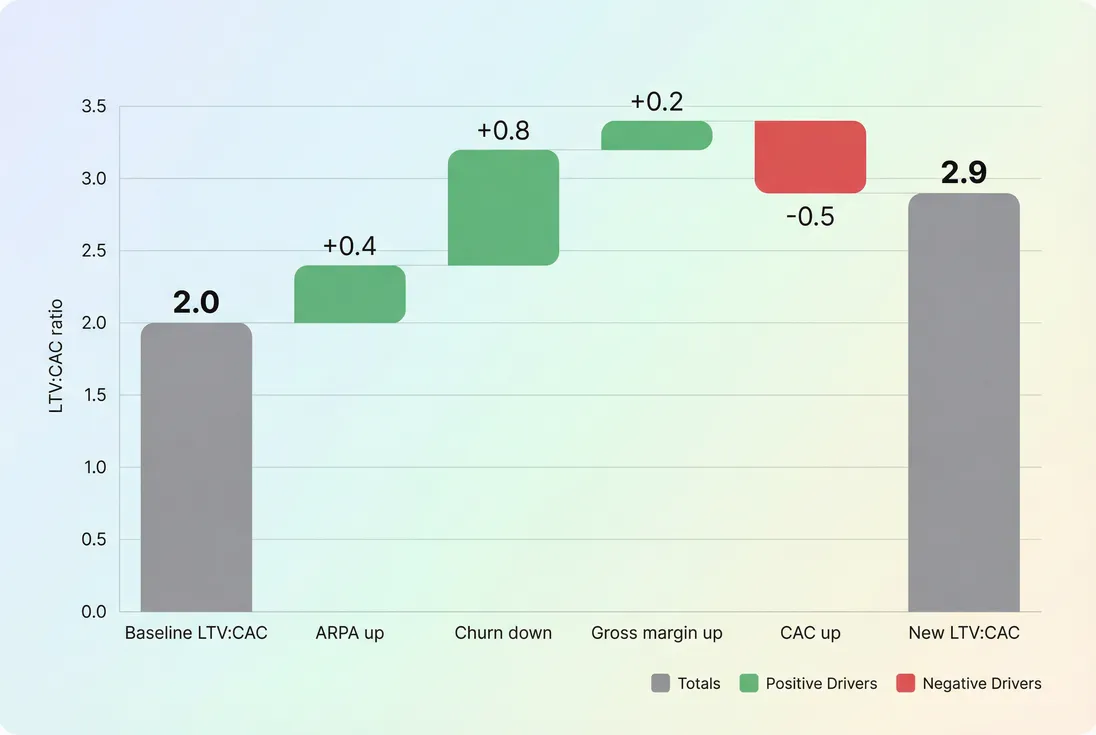

What actually moves LTV:CAC

Founders often ask, "Should I focus on lowering CAC or increasing LTV?" The answer is: do the one with the biggest, fastest, most repeatable lift for your business—then verify the change shows up in new cohorts, not just averages.

*A ratio rarely improves by accident. This bridge view makes it obvious whether LTV is rising (pricing, margin, retention) or CAC is falling (conversion, channel mix).*

The highest-leverage LTV drivers

Retention (logo churn)

- Small churn changes create big LTV swings because churn is in the denominator.

- Example: monthly logo churn drops from 3% to 2% → lifetime rises from ~33 months to 50 months (~50% increase), often beating most CAC optimizations.

Expansion

- If customers expand, LTV rises even if logo churn stays flat.

- This is why NRR-focused businesses can sustain higher CAC and still win long-term (see Net Negative Churn and Expansion MRR).

Pricing and packaging

- Raising prices increases ARPA, but may increase churn or reduce conversion. LTV:CAC forces you to confront that tradeoff with numbers rather than opinions.

Gross margin

- If your support or infrastructure costs scale with revenue, your "revenue LTV" can look great while gross profit LTV is mediocre. Tightening COGS can be equivalent to a major CAC improvement.

The CAC drivers that matter in practice

Conversion rate across the funnel

- Improving lead-to-customer conversion often beats negotiating ad CPMs.

- See Conversion Rate, Lead-to-Customer Rate, and Win Rate.

Sales cycle length and discounting

- Long cycles increase cost per win and often pressure discounting, which also hurts LTV.

- See Sales Cycle Length and Discounts in SaaS.

Channel mix

- A blended CAC hides that one channel prints money while another destroys value. Segment CAC and LTV by source/intent.

The Founder's perspective: If you can only do one thing this quarter, choose the lever that changes both sides. Example: improving onboarding can increase retention (LTV up) and improve referrals or trial conversion (CAC down). Those compounding fixes are how strong ratios are built.

How founders use it to make decisions

LTV:CAC becomes powerful when it's tied to a decision rule. Here are common founder decisions it supports, and how to apply it without overconfidence.

1) Deciding whether to scale sales and marketing

Use LTV:CAC as a gate, but require two additional checks:

- Cohort confirmation: New-customer retention for recent cohorts should not be deteriorating. Use Cohort Analysis to confirm you're not buying lower-quality customers at scale.

- Payback tolerance: Your cash position sets the maximum payback you can tolerate (see Runway and CAC Payback Period).

A practical rule many teams adopt:

- Scale when LTV:CAC is comfortably above your target and payback is within your cash tolerance.

- Hold spend flat when the ratio is acceptable but volatile.

- Cut or reallocate when the ratio drops for two or more periods and the drop is explained by cohort retention (not just a one-off CAC spike).

2) Choosing between pricing work and retention work

A quick diagnostic:

- If CAC is stable but LTV:CAC is falling, your LTV is degrading (often churn rising or expansion weakening).

- If retention is stable but LTV:CAC is falling, your CAC is inflating (channel saturation, worse targeting, weaker conversion).

Use the ratio to pick the workstream, then use deeper metrics to execute:

- Retention work: Customer Churn Rate, GRR (Gross Revenue Retention), NRR (Net Revenue Retention)

- Pricing work: ASP (Average Selling Price), ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account)

3) Setting quotas and hiring plans

If you're adding sales headcount, CAC often rises before it falls (ramp time, enablement, experimentation). LTV:CAC helps you set expectations:

- Model CAC temporarily increasing (new reps are expensive).

- Require that cohort LTV doesn't drop (bad ICP expansion can make CAC look better briefly while LTV collapses later).

- Track segment-level performance: SMB motion economics rarely map cleanly to enterprise economics.

4) Managing discounting pressure

Discounts impact both sides:

- They can reduce CAC (higher win rate, faster cycles).

- They also reduce LTV (lower ARPA) and sometimes attract worse-fit customers (higher churn).

When discounting becomes a habit, LTV:CAC is often the first metric that quietly deteriorates—especially if you only look at bookings or pipeline.

When the metric breaks (and what to do)

LTV:CAC is easy to misuse. Here are the most common failure modes—and the fix.

It breaks when you mix time periods

If CAC is from Q1 but LTV is estimated from all customers (including older cohorts with different pricing and retention), the ratio is not a decision tool.

Fix: calculate LTV on the same acquisition cohorts that incurred the CAC, or at least segment by acquisition period.

It breaks when you use optimistic churn

Early-stage churn often improves as onboarding, ICP, and product maturity improve. But it can also worsen when you scale channels and broaden targeting.

Fix: use cohort-based retention and conservative assumptions. If you must estimate, use the retention of the most recent stable cohorts, not "best-ever" cohorts.

It breaks when expansion and contraction are ignored

If you only use logo churn, you'll understate LTV in expansion-heavy products and overstate it in contraction-heavy ones.

Fix: sanity-check LTV assumptions against revenue retention (see NRR (Net Revenue Retention) and Contraction MRR). Even if you keep a logo-churn-based LTV for simplicity, don't ignore what your retention curves are telling you.

It breaks when big customers dominate averages

A handful of large accounts can make LTV:CAC look elite while the core business is mediocre.

Fix: segment by plan size and ICP, and watch concentration risk (see Customer Concentration Risk).

The Founder's perspective: If your ratio depends on a small number of whales, treat it like a fragile advantage. You don't have a scalable growth model yet—you have a few great wins.

A practical operating cadence

If you want LTV:CAC to drive behavior (not just reporting), adopt a cadence like this:

- Monthly: review CAC by channel and segment; flag sudden CAC inflation.

- Quarterly: review cohort retention trends; refresh LTV assumptions.

- Quarterly decision: set an explicit spend posture (scale, hold, or reallocate) based on ratio and payback.

A useful workflow is:

- Start with retention/cohorts to validate LTV inputs (see Retention and Cohorts).

- Confirm ARPA and pricing movement (see ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account) and MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue)).

- Compare LTV changes to CAC changes, then decide where to focus.

LTV:CAC is not a trophy metric. It's a decision constraint: it tells you whether growth spend is building long-term value or borrowing from the future. Treat it as a segmented, cohort-aware model—paired with payback—and it becomes one of the clearest signals for when to scale, when to fix fundamentals, and where the real leverage is in your SaaS business.

Frequently asked questions

For many SaaS businesses, 3 to 5 is healthy, under 2 is a warning, and over 5 can mean you are underinvesting in growth. But the right target depends on payback speed, retention durability, and how confident you are that today's cohorts will behave like yesterday's.

LTV:CAC can be high while cash burn stays high if CAC payback is slow, deals are annual and billed later, or sales and marketing costs scale ahead of revenue recognition. Pair the ratio with CAC payback and burn metrics to understand timing, not just eventual profitability.

Use gross profit LTV for decision-making because CAC is paid in cash and COGS is real. Revenue LTV can overstate unit economics, especially for low-gross-margin products, heavy support needs, or infrastructure-heavy usage. If you report revenue LTV, show gross margin alongside it.

Segment by customer type and acquisition motion, and use cohort-based retention where possible. Blended ratios hide that enterprise may be 6 while SMB is 1.5. Also align time periods: the CAC you spend this quarter should be compared to the LTV of customers acquired this quarter.

Increase spend when the ratio is solid and stable across recent cohorts and payback is acceptable for your cash position. Decrease or pause scaling when the ratio deteriorates, varies wildly by channel, or depends on optimistic churn assumptions. Fix conversion, pricing, or retention before hiring more sales capacity.