Table of contents

Ideal customer profile (ICP)

If you don't have an ICP, you'll build a company that needs constant heroics to grow. Sales will chase "anyone with budget." Product will ship for edge cases. Support will drown. Churn will look "mysterious" because you're selling to people who were never going to win with your product.

The payoff of a real ICP is boring in the best way: higher win rates, faster onboarding, better retention, and more predictable growth. You stop arguing about opinions and start making decisions off patterns.

Plain-English definition: an ideal customer profile (ICP) is the specific type of customer that reliably gets value from your product and reliably creates value for your business. Not who "could" use it. Who actually succeeds, sticks, and pays.

ICP shows up as a cluster of better business outcomes in one segment: faster value, higher retention, and stronger revenue—not just more leads.

What ICP really tells you

ICP is not a persona. It's not "marketing positioning." It's a profitability and retention filter.

A usable ICP answers, in order:

- Who gets value fast? (short time to value, low onboarding friction)

- Who sticks? (strong retention, low churn, low refunds/chargebacks)

- Who expands or stabilizes revenue? (healthy expansion, low contraction)

- Who is efficient to serve? (reasonable support + implementation cost)

- Who is reachable? (you can actually acquire them at an acceptable CAC)

If your ICP doesn't improve decisions in at least two departments (sales + product, or marketing + CS), it's too vague.

The founder's perspective

ICP is how you stop fundraising to cover churn. If retention is weak, every "growth" month is a treadmill. A tight ICP turns growth into compounding, not constant replacement.

ICP is a choice, not a discovery

Founders mess this up by treating ICP like a hidden truth they must "find." You choose it based on evidence and strategy.

- Evidence: which customers are already successful and profitable.

- Strategy: which customers you want to win long-term (because the market, product, and economics line up).

That means you can have multiple "good" segments. The job is to pick a primary one so execution stops being scattered.

How to define ICP using outcomes

Start with customers you already have. Not leads. Not trials. Paying customers with enough time in the product to reveal truth.

Your raw materials:

- Revenue quality: MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue), plan mix, discounting patterns

- Retention quality: Customer Churn Rate, Logo Churn, NRR (Net Revenue Retention), GRR (Gross Revenue Retention)

- Value delivery speed: time to first key action, time to first outcome (business event)

- Cost to serve: support tickets, onboarding time, implementation load

- Acquisition efficiency: CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost), CAC Payback Period, Sales Cycle Length

If you use GrowPanel, this is where you use filters, customer list, retention, and cohorts to compare outcomes by segment (industry, size, plan, acquisition channel, geography). See Filters and Cohorts.

A practical ICP scoring model (useful, not perfect)

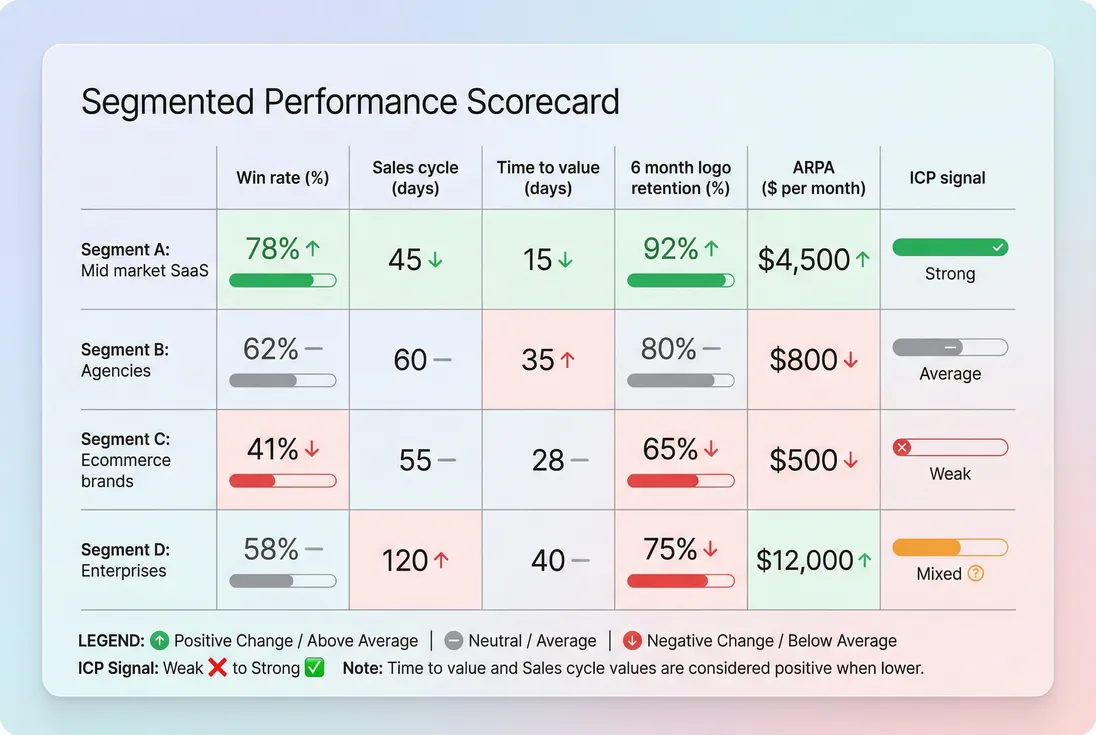

ICP is qualitative, but you can quantify fit to force clarity and reduce internal arguments.

Here's a simple weighted score:

- \text{w} = weight (what you care about most)

- \text{s} = standardized segment score (how that segment performs)

Keep it boring. Use 5–7 signals max. Example signals:

- 90-day logo retention

- 6-month NRR

- Time to value (days)

- ARPA or ASP (revenue level)

- Support hours in first 30 days

- Win rate

- Sales cycle length

If you want one "north star" composite for go-to-market prioritization, use an expected value lens:

Not because the formula is holy—because it forces tradeoffs into the open. High ARPA with low retention is not "premium." It's unstable.

The minimum viable dataset

You don't need perfection. You need enough to see separation.

A good rule of thumb:

- At least 10–15 customers per segment you're comparing (even if segments are rough).

- At least 90 days of behavior for churn-prone products (longer for annual contracts).

If you don't have that, start with qualitative signals (why they bought, what they replaced, what "success" looks like) and validate with early retention signals.

The ICP tradeoffs you can't avoid

Every ICP choice comes with a cost. Pretending otherwise is how you end up with a generic product and mediocre economics.

Here are the real tradeoffs founders should discuss explicitly:

| ICP choice | What you gain | What you give up | Watch-outs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Narrower (one clear segment) | Higher win rate, faster onboarding, clearer roadmap | Less top-of-funnel volume | Pipeline panic pushes you to broaden too early |

| Higher ARPA segment | Bigger deals, more revenue per logo | Longer cycles, higher expectations | "Enterprise" customers demand features you can't support |

| Lower ARPA, high volume | Fast cycles, self-serve motion | More churn risk, support scaling | You confuse "signups" with a business |

| Complex regulated buyers | Higher switching costs | Heavy compliance and implementation burden | You become a services company accidentally |

The founder's perspective

The ICP decision is really: "Where do we want to be world-class?" Because you will be average everywhere else. That's not pessimism. It's resource reality.

When ICP breaks down

Most ICPs fail for the same reasons: they're written as demographics, not outcomes.

Failure mode 1: "We sell to SMBs"

"SMB" is not an ICP. It's a revenue bracket.

Two companies with 50 employees can behave completely differently:

- One has a clear owner, urgent pain, and budget authority.

- One is committee-driven, change-averse, and slow.

Fix: define situations, not just firmographics:

- Trigger events (hiring, compliance deadline, tooling migration)

- Existing stack (what you integrate with / replace)

- Buying model (self-serve vs sales-assisted)

- Success criteria (what must be true in 30 days)

Failure mode 2: confusing enthusiasm with fit

Some leads love your demo. They're still bad customers.

Bad-fit customers often show up as:

- High pre-sales excitement

- Heavy customization requests

- Slow implementation

- High support load

- Early churn or non-renewal

Fix: treat early churn as an ICP signal, not a CS failure. Use Churn Reason Analysis to separate "product gap" from "bad match."

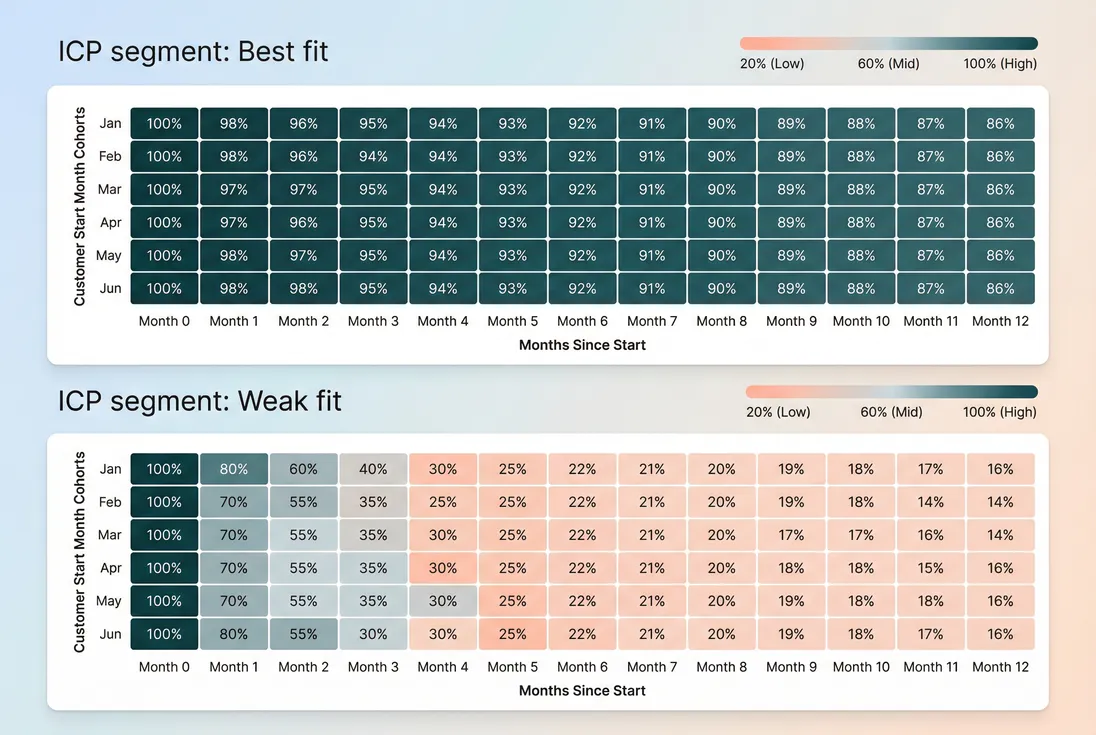

Failure mode 3: you ignore cohort truth

If you only look at blended churn, your best segment gets diluted by your worst segment. Then you make the wrong roadmap and pricing calls.

Fix: use Cohort Analysis by segment. You're looking for:

- cohorts that stabilize

- cohorts that expand

- cohorts that decay fast

If one segment's cohorts consistently retain better, that's your ICP trying to tell you something.

Blended retention hides the truth. Cohorts split by ICP fit show whether churn is a product problem or a targeting problem.

What actually changes your ICP

ICP isn't static. It moves when your product and economics move. The mistake is letting it drift without noticing—then your go-to-market becomes inconsistent.

Pricing changes ICP (even if you deny it)

Raise price and you implicitly move upmarket. Add a low entry plan and you invite different buyers with different churn behavior.

Watch metrics by plan and segment:

- ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account) and ASP (Average Selling Price)

- retention and churn by plan

- discount frequency (if you rely on heavy discounting, your "ICP" might be "people who bargain")

If you discount to close deals in a segment, that segment is telling you it doesn't value the product at list price. Believe it.

Related: Discounts in SaaS.

Product maturity changes ICP

Early product: you often win with "builders" and "early adopters." Later: you win with "operators" who want reliability and predictable workflows.

If you keep selling to early adopters after you've matured, you get:

- feature churn (they leave for novelty)

- high change requests

- low willingness to standardize

If you try to sell to operators too early, you get:

- security questionnaires you can't answer

- procurement you can't navigate

- churn from unmet expectations

Your ICP should match what your product can reliably deliver today—not your future roadmap.

Channel changes ICP (and vice versa)

Different channels attract different levels of urgency and budget authority.

- SEO content tends to pull researchers and early-stage teams.

- Partner channels can pull higher intent, but require trust and enablement.

- Outbound can be great if your ICP is narrow enough to target precisely.

If one channel is "working" but retention is weak, the channel is not working. It's just producing revenue-shaped problems.

Tie channel performance back to retention and revenue quality:

- win rate and sales cycle by channel

- 90-day retention by channel

- NRR by channel

This is why ICP is not just marketing's job.

How founders use ICP in real decisions

A real ICP is operational. Here's how it should change what you do next week.

Sales: qualify harder, lose faster

Your ICP should create disqualifiers. If everything is a "maybe," you don't have an ICP—you have hope.

Examples of strong disqualifiers:

- They don't have the trigger event that creates urgency.

- They lack the internal owner for the problem.

- Their stack can't support your workflow (or would require heavy services).

- Their success metric doesn't match what your product delivers.

Then instrument it:

- Track win rate and sales cycle for "ICP fit: high" vs "ICP fit: low"

- Compare downstream churn. If low-fit deals churn faster, you've proven the economic cost of weak qualification.

Related: Win Rate and Sales Cycle Length.

Marketing: stop optimizing for cheap leads

Cheap leads are not cheap if they churn. If you care about business impact, you optimize for profitable retained customers, not signups.

What to change:

- Rewrite landing pages to speak to the ICP situation and trigger.

- Remove generic benefits. Add specific outcomes and constraints.

- Publish content that filters out bad-fit buyers (yes, on purpose).

If your content never says "this is not for you," you'll keep paying to educate people who will never retain.

Product: simplify for the winner

Your roadmap should get simpler when ICP is clear.

Do more of:

- features that accelerate time to value for the ICP

- integrations the ICP already uses

- permissioning and workflows that match their buying model

Do less of:

- one-off features for large-but-misaligned customers

- "nice-to-haves" that don't move retention or expansion

This is where founder discipline matters. One enterprise logo can hijack a roadmap for a year. Unless that segment is your chosen ICP, it's usually not worth it.

Customer success: design onboarding for the ICP

If onboarding tries to serve everyone, it serves no one.

Build an ICP-specific onboarding path:

- a shorter "first win" checklist

- success milestones aligned to their job

- proactive risk flags (usage drop, stalled setup)

Then measure:

- onboarding completion rate by segment

- time to value by segment

- early churn by segment

If a segment can't get value without heavy hand-holding, that's not automatically "bad." But it must pay for that cost to serve.

Finance: align spend with retention reality

Your ICP determines what you can responsibly spend on acquisition.

Healthy ICP → better retention → better LTV → more CAC headroom. Weak ICP → CAC is a trap.

Use LTV (Customer Lifetime Value) and LTV:CAC Ratio by segment if you can. If you can't yet, use retention and ARPA as leading indicators.

Also watch customer concentration if your ICP is "big accounts." See Customer Concentration Risk.

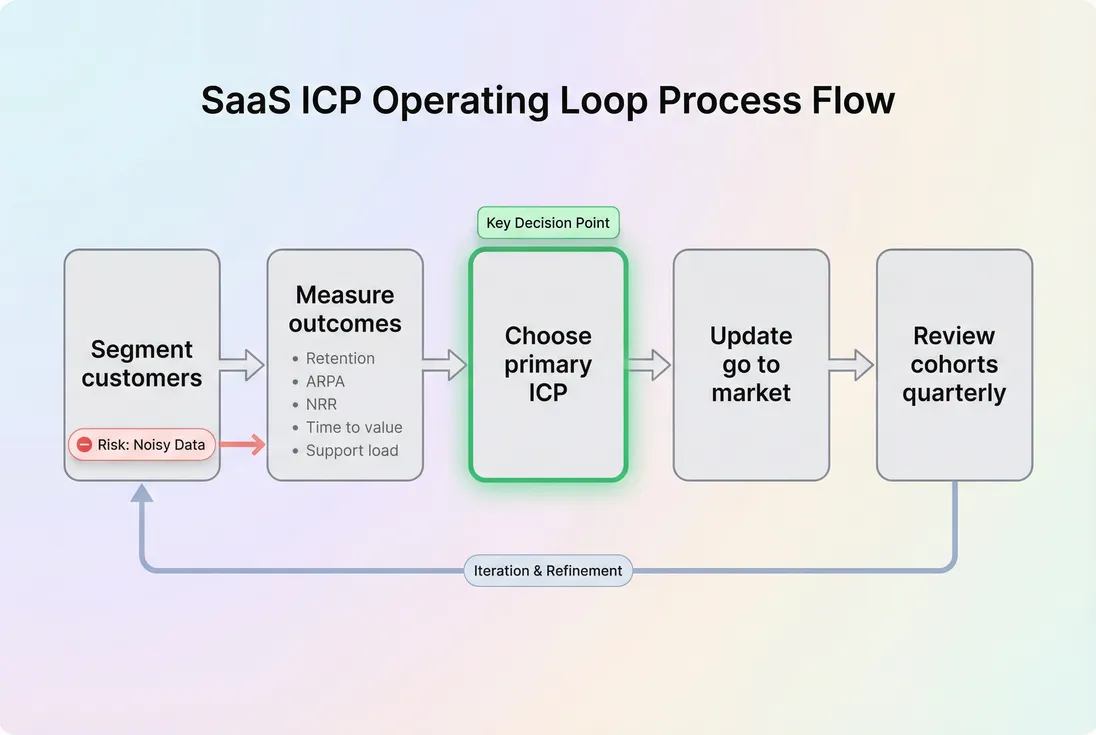

A founder-grade ICP workflow

You don't need a fancy framework. You need a repeatable loop.

- Segment customers by the few attributes you can trust (industry, size, use case, plan, acquisition channel).

- Compare outcomes: retention, ARPA, expansion, time to value, support load.

- Pick a primary ICP (and write down who you're deprioritizing).

- Change the go-to-market to match (qualification, messaging, pricing, onboarding).

- Re-check cohorts quarterly and tighten.

ICP is an operating loop. The point is to force better decisions, then revisit with cohort evidence—not to create a static document.

What to watch vs what to ignore

You'll drown if you track everything. Here's what matters.

Watch these signals (by segment)

- Retention first: GRR (Gross Revenue Retention) and logo retention

- Revenue quality: ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account) and expansion

- Speed: time to value, sales cycle length

- Efficiency: CAC payback, support load

- Discount dependence: if a segment only closes with discounts, treat that as low willingness to pay

If you use GrowPanel, segment these with filters and sanity check individual accounts in customer list before making big calls.

Ignore (or demote) these early on

- Total addressable market arguments when your retention is weak

(TAM doesn't fix churn.) - Top-of-funnel volume by itself

(volume without retention is vanity.) - "Average customer" narratives

(there is no average customer; there are segments.)

The founder's perspective

If you're arguing about ICP in abstract terms, you're avoiding the real question: which customers are actually making you money after accounting for churn and cost to serve?

What to do next (a tight action list)

- Pull a customer list and tag your last 30–50 wins by 3–5 attributes you can reliably identify (industry, size, use case, plan, channel).

- Compare segments on outcomes: 90-day retention, 6-month retention, ARPA, time to value.

- Write a one-paragraph ICP that includes:

- firmographics (who)

- situation/trigger (when)

- required capability (what must be true)

- disqualifiers (who you will say no to)

- Update qualification: make ICP fit explicit in your pipeline process.

- Run one quarter focused: fewer segments, tighter messaging, product changes that reduce time to value for the ICP.

- Re-read cohorts: if retention and expansion improved in the chosen ICP, double down. If not, your hypothesis was wrong—adjust fast.

If you want a clean way to validate the decision, tie it to retention views and cohort splits (see Retention and Cohorts). ICP isn't "branding." It's measurable behavior.

Related Academy concepts

- Cohort Analysis

- NRR (Net Revenue Retention)

- ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account)

- CAC Payback Period

- Churn Reason Analysis

Frequently asked questions

You're too early only if you don't have enough closed-won customers to compare outcomes. With 15–30 paying customers, you can usually see patterns in time to value, support load, and early churn. ICP is a hypothesis you tighten quarterly, not a "final answer" you wait to discover.

Look for mismatch between acquisition and retention: strong top-of-funnel interest but weak activation, high logo churn, or low expansion in the first 90–180 days. If one segment has meaningfully better retention and ARPA, your current ICP is too broad or your channel is attracting the wrong buyers.

Optimize for retention first unless you already have consistently low churn. High ARPA with poor retention creates fake growth and forces nonstop acquisition. A smaller customer that sticks and expands is worth more than a "big" customer that churns in three months. Revenue is the output; retention is the engine.

Narrow enough that your sales and product choices get simpler. If your ICP statement still fits half the internet, it's not useful. The tradeoff is volume: you'll lose some leads, but you'll gain win rate, shorter sales cycles, and better retention. If pipeline drops, fix targeting—not the ICP.

Compare segments on win rate, sales cycle length, ARPA, gross retention, and expansion within 6–12 months. If you can only pick two, pick retention and ARPA. Those determine LTV and how much you can spend on CAC without burning the business. Everything else is secondary.