Table of contents

Customer growth rate

Founders don't miss growth because they lack dashboards—they miss it because they confuse busy with net adds. Customer growth rate forces a simple truth: if you aren't adding customers faster than you're losing them, every "growth" initiative is just replacing churn.

Customer growth rate is the percentage change in your active customer count over a period (usually month-over-month or quarter-over-quarter). It answers: How fast is my customer base actually expanding?

What this metric reveals

Customer growth rate is a volume signal. It tells you whether your go-to-market is producing a larger customer footprint, which affects:

- Future expansion opportunity (more accounts that can upgrade later)

- Support and onboarding load (headcount planning)

- Risk profile (a broader base can reduce Customer Concentration Risk)

- The "shape" of revenue growth when combined with ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account) and Revenue Growth Rate

A common pattern in SaaS:

- Customer growth rate is strong, but revenue growth is weak → you're adding smaller customers, discounting heavily, or churning higher-priced accounts.

- Customer growth rate is weak, but revenue growth is strong → you're expanding existing accounts, raising prices, or moving upmarket (good, but watch concentration and pipeline).

The Founder's perspective

If your customer growth rate is slowing, your first job is to determine whether you're hitting a market ceiling (top-of-funnel problem) or leaking customers (retention problem). The decision tree changes hiring, messaging, roadmap priorities, and how aggressively you can spend on acquisition.

How to calculate it

At its simplest, calculate it from start and end active customers for the period:

Where "customers" should match your definition of active customer count (typically paying customers with an active subscription). If you haven't standardized that definition, start with Active Customer Count and document it internally.

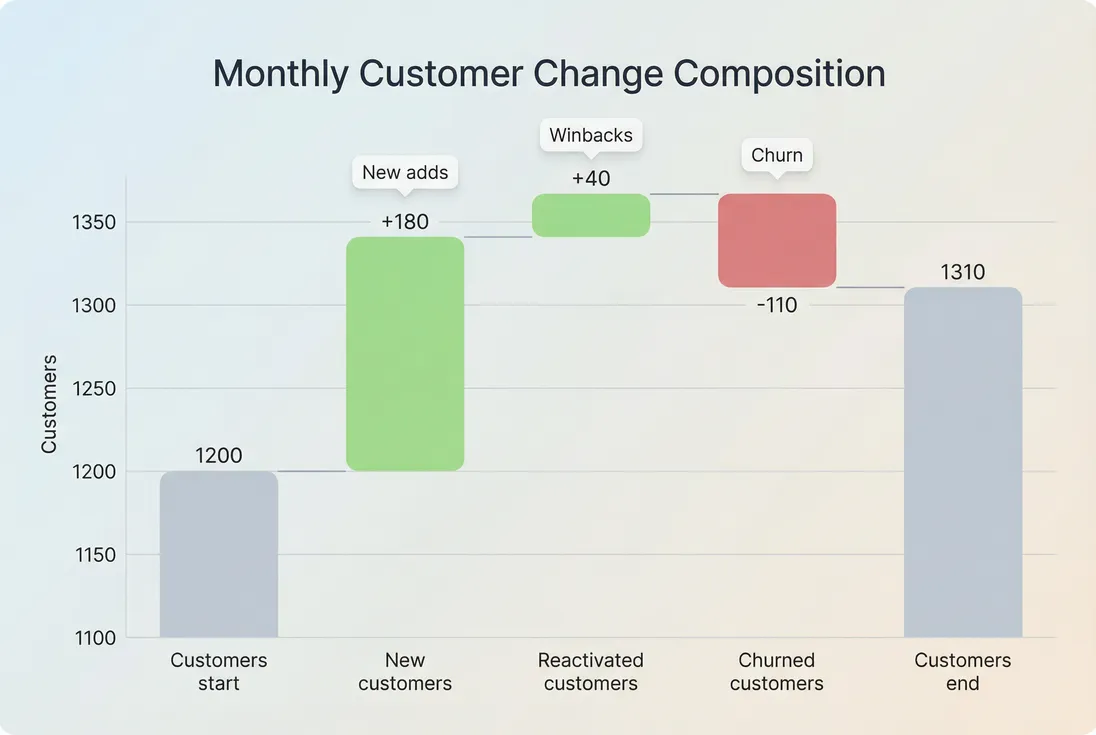

Net adds view (more actionable)

Founders get more insight by decomposing the change:

That decomposition matters because "10% growth" can come from very different realities:

- Healthy: high new adds, low churn

- Fragile: high new adds, high churn (treadmill)

- Misleading: low new adds, low churn (stable, but not scaling)

What counts as a "customer"

This is where teams quietly break the metric.

A practical default: count customers with an active, paid subscription at the end of the period.

Decide and document how you handle:

- Trials: usually excluded (track separately via Free Trial)

- Freemium users: exclude from "customers" unless they are the unit you monetize later (if so, split free vs paid; see Freemium Model)

- Paused subscriptions: exclude if not paying and not receiving service

- Annual prepaid customers: still count as customers each month; customer count is independent of cash timing (see Deferred Revenue for finance implications)

- Multiple workspaces under one contract: count at the contract level if churn/renewal happens at the contract level

If you're inconsistent, your growth rate becomes a tracking artifact instead of a business signal.

The Founder's perspective

The goal isn't the perfect definition—it's a stable definition. A consistent customer count lets you compare periods and understand cause and effect. Change the definition only when your business model changes, and restate historicals if possible.

What drives customer growth rate

Customer growth rate is the result of three levers. Treat them separately.

1) New customer acquisition

New adds depend on your acquisition engine and your conversion path:

- Lead flow and quality (see MQL (Marketing Qualified Lead) and SQL (Sales Qualified Lead))

- Conversion efficiency (see Lead-to-Customer Rate and Conversion Rate)

- Sales execution constraints (see Sales Cycle Length and Win Rate)

Operationally, this is where founders often over-invest because it feels controllable. But acquisition only creates durable growth if churn stays in check.

2) Customer churn

Churn is the tax on growth. Customer growth rate can look fine until churn rises, then it collapses quickly because churn hits your existing base.

Track churn alongside:

- Customer Churn Rate (logo churn)

- Logo Churn (often used interchangeably; define your terms)

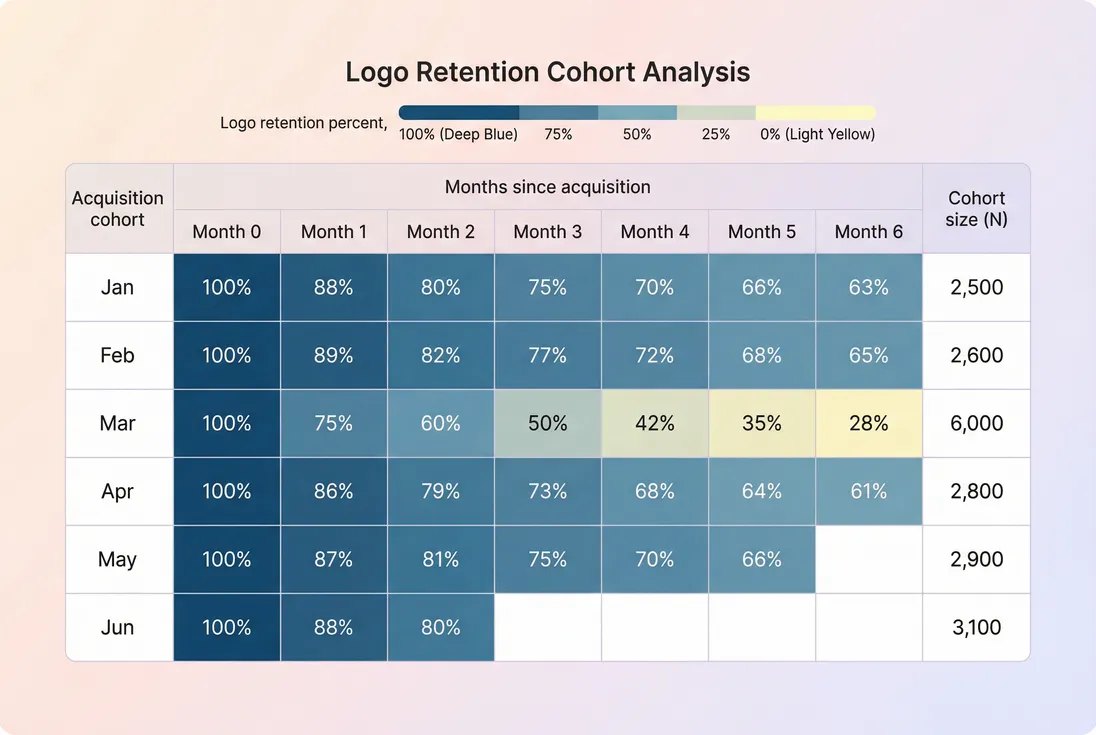

- Retention by cohort (see Cohort Analysis and Retention)

If customer growth slows, check whether churn increased in a specific segment (plan, industry, channel, tenure). That tells you whether to fix product value, onboarding, pricing, or targeting.

3) Reactivations

Reactivations (customers who return after churn) can matter more than founders expect—especially in SMB, seasonal, or budget-constrained markets.

Reactivations can signal:

- Your product is valuable but not sticky (customers come back when they "need it")

- Pricing and packaging friction (customers leave to reduce spend, return later)

- Operational churn (cancellations due to billing failures or procurement timing; see Involuntary Churn)

Reactivations are real growth, but they often indicate you should improve retention mechanics rather than just "win them back."

How to interpret changes (without fooling yourself)

Growth rate falls as your base grows

Even if you add the same number of customers each month, the percentage growth rate declines as the starting base increases.

Example:

| Month | Customers start | Net adds | Customers end | Growth rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| January | 200 | 40 | 240 | 20% |

| June | 800 | 40 | 840 | 5% |

Nothing "broke"—your company is simply larger. This is why many teams also track net customer adds as a raw number alongside the rate.

Mix changes can hide revenue problems

Customer growth rate doesn't tell you whether those customers are good customers.

Pair it with:

- ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account) to spot down-market drift

- ASP (Average Selling Price) to catch discounting or packaging dilution

- MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue) and Revenue Growth Rate to connect customer volume to dollars

- Retention metrics like GRR (Gross Revenue Retention) and NRR (Net Revenue Retention) to know if the base expands after purchase

Concrete interpretation:

- Customer growth up, ARPA down → you're adding smaller deals or discounting (could be intentional in PLG, dangerous in enterprise)

- Customer growth down, NRR up → existing customers are expanding; you may be capacity constrained in acquisition, or intentionally moving upmarket

One big churn event can distort the trend

Customer growth rate is noisy when your base is small or when you have a few "whale" accounts. If you have meaningful whale risk, read Cohort Whale Risk and segment customers by size.

A practical approach:

- Review the metric monthly, but manage the business on a trailing average like T3MA (Trailing 3-Month Average) for stability.

- Segment: SMB vs mid-market vs enterprise. The combined rate can mislead.

Promotions and annual renewals create seasonality

If you run annual contracts or heavy Q4 discounting, customer adds and churn may cluster. Growth rate is still valid, but you must interpret it with the calendar and contract timing in mind (see Average Contract Length (ACL)).

Benchmarks and targets (use carefully)

There is no universal "good" customer growth rate, but you can use ranges to sanity-check plans. Here's a practical lens:

| Company stage | Typical healthy monthly customer growth rate | What matters most |

|---|---|---|

| Early (small base) | 10% to 30% | Finding a repeatable acquisition channel and fixing onboarding |

| Growing (proving scale) | 5% to 15% | Holding churn flat while scaling acquisition and sales capacity |

| Mature (large base) | 1% to 5% | Retention, expansion, segmentation, and efficiency |

Use benchmarks as a diagnostic, not a goal. A company with 2% monthly customer growth and excellent NRR can be far healthier than a company at 15% growth with severe churn and poor CAC Payback Period.

The Founder's perspective

When investors ask about growth, they're really asking: is there a reliable system here? Customer growth rate is one of the quickest ways to show whether your acquisition engine beats your churn engine—before you even talk about revenue.

How founders use it in real decisions

1) Decide whether to scale acquisition

If customer growth is slowing, don't default to "spend more on marketing." First isolate whether the slowdown is:

- Fewer new customers (top-of-funnel, conversion, sales capacity)

- More churn (product value, onboarding, support, pricing)

- A denominator effect (same net adds on a bigger base)

Then decide:

- If new adds are the issue and retention is stable, scaling spend can work—validate with CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost) and payback.

- If churn is the issue, scaling acquisition often worsens your economics and support burden.

Tie the decision to efficiency guardrails like Burn Multiple and Capital Efficiency.

2) Plan onboarding and support capacity

Customer growth rate is an early warning for operational load. If you grow customers 8% per month, your onboarding tickets, implementation calls, and support queue will compound too—unless you invest in self-serve activation.

Pair this metric with:

- Onboarding Completion Rate

- Time to Value (TTV)

- Product usage signals like DAU/MAU Ratio (Stickiness)

3) Evaluate positioning and packaging shifts

A packaging change can increase customer growth while hurting long-term value (or the reverse).

Example scenarios:

- Introducing a low-priced entry plan increases customer growth rate but lowers ARPA and may increase churn if the segment is misfit.

- Raising prices may reduce new adds short-term but improve retention and expansion if it funds better service and aligns value.

If you changed pricing, also review Discounts in SaaS to ensure your reporting reflects true customer value and doesn't inflate "growth" via short-term promos.

4) Spot channel quality problems early

Two channels can produce the same customer growth rate with very different churn profiles. Segment growth and churn by acquisition source and compare early retention by cohort.

A simple rule: if a channel's customers churn materially faster, it's not "growth"—it's churn replacement with extra work.

When this metric breaks

Customer growth rate becomes unreliable when your customer "unit" is inconsistent or when your business model doesn't map cleanly to customers.

Watch out for:

- Multi-product bundles: customers can "churn" one product but keep another—decide whether your customer count is per product or per account.

- Resellers and marketplaces: one "customer" might represent many end users; complement with Active Users (DAU/WAU/MAU).

- Usage-based pricing: customers may not churn but may go dormant. Combine with retention and usage measures, and consider how you define "active." (See Usage-Based Pricing.)

If you're unsure, keep the customer definition strict (paid active subscriptions) and build separate operational metrics for activation and usage.

Practical workflow to improve it

- Decompose net change monthly: new, reactivated, churned.

- Segment by plan size and channel using consistent filters.

- Run a cohort view monthly to see if new customers stick.

- Pick one constraint to fix per cycle:

- Acquisition constraint → improve conversion, shorten sales cycle, raise win rate

- Churn constraint → fix onboarding, reduce time-to-value, align pricing and ICP

- Validate economics before scaling with CAC payback and burn multiple.

If you use GrowPanel, this is where the customer list and filters are most practical: review which accounts entered and left the base, then segment the trend to find where growth is real versus where it's being canceled by churn.

Related metrics to read next

Frequently asked questions

Customer growth rate measures changes in the number of active customers, not dollars. Revenue can grow even when customers decline if ARPA rises, and customers can grow while revenue lags if you add low priced plans. Use it alongside Revenue Growth Rate and ARPA to spot mix shifts.

It depends on stage, market, and sales motion. Early stage products often target high double digit monthly growth from a small base. Mature mid market and enterprise businesses may be healthy at low single digit monthly growth with strong retention. Judge it with churn, CAC payback, and capacity.

Only if they are truly active customers under your business definition. Most SaaS teams count paying active subscriptions, excluding trials and free users, because retention and churn logic depends on it. If you run freemium, track customer growth separately for paying and free segments to avoid confusion.

Growth rate is net of churn and is sensitive to your starting base. You can have more signups but also more churn, or you can grow from a larger starting customer count which mechanically lowers the percent. Break it into new, reactivated, and churned customers to find the real driver.

Treat it as a capacity planning input. If growth is accelerating with stable churn, you may need more onboarding, support, and sales coverage. If growth relies on high churn replacement, prioritize retention work before scaling acquisition spend. Pair it with CAC Payback Period and Burn Multiple to stay efficient.