Table of contents

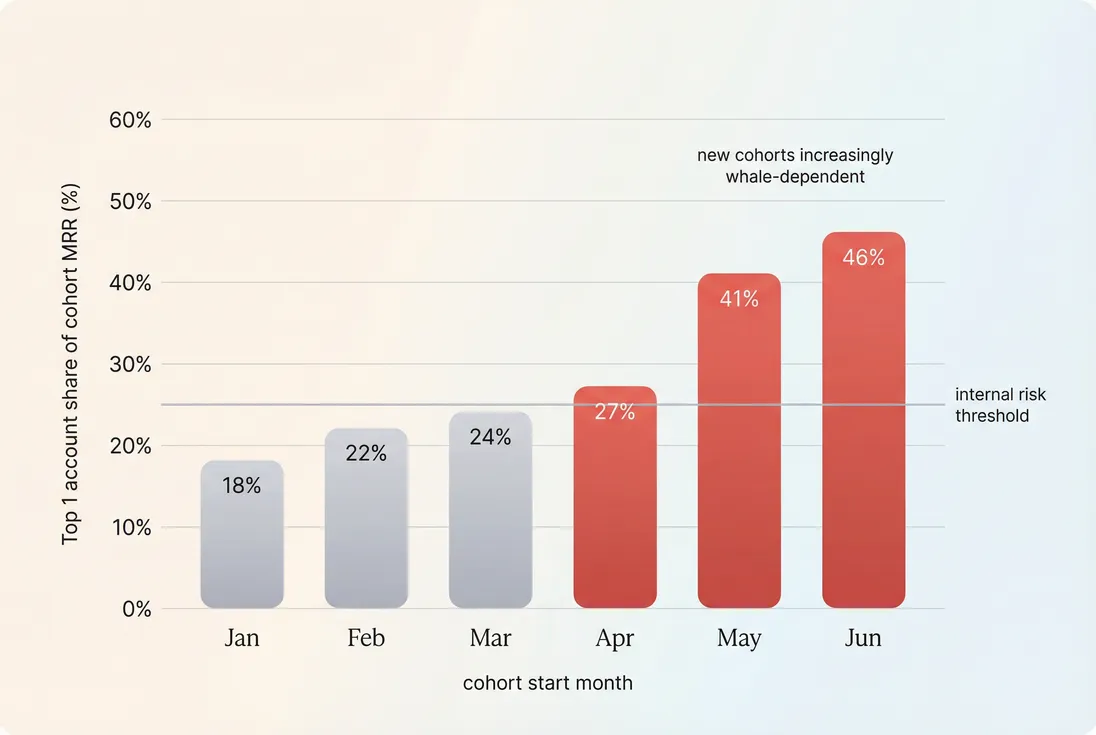

Cohort whale risk

A lot of "growth" looks great until you realize the newest cohort is being carried by one or two oversized customers. When one of them delays renewal, downgrades, or churns, your forecast misses, your hiring plan becomes risky, and your sales team scrambles to backfill a hole that never should have been invisible.

Cohort whale risk is the share of a cohort's current recurring revenue that comes from its largest accounts. It tells you whether a cohort's revenue is broadly distributed (resilient) or concentrated in a few whales (fragile).

Top-1 share by cohort makes concentration visible early—before a single churn event rewrites your plan.

What this metric reveals

Cohort whale risk answers a founder's practical question: if this cohort loses one account, how much revenue disappears?

It's especially useful when you already do Cohort Analysis for retention, but want to understand why some cohorts behave differently:

- A cohort can have "good" retention on average while being dangerously dependent on one expanding whale.

- Another cohort can have mediocre retention but low whale risk because revenue is evenly spread (often easier to fix with onboarding and activation work).

Cohort whale risk is also a fast way to detect GTM drift:

- Your pricing or packaging introduced a steep jump (one account now dwarfs the cohort).

- Sales started landing a few large deals but you stopped adding enough mid-tier accounts.

- The long tail is churning, making the whale's share rise even if the whale didn't expand.

The Founder's perspective

If one customer can swing your month by 10–20% of cohort revenue, you do not have "predictable growth." You have a concentration bet. That changes how aggressive you can be with hiring, how you set quotas, and how you talk about risk with investors.

How to calculate it

You need three choices to make the metric operational:

- Define the cohort. Most teams use "first paid month" (customers whose subscription started in the same month).

- Pick the revenue basis. Typically current MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue) at a point in time. Some teams use ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue) for annual contracts.

- Pick a whale definition. Common options:

- Top 1 account share (simple, very interpretable)

- Top 3 or top 5 share (captures "a few whales")

- HHI (more sensitive to distribution, less intuitive)

Core formula (top k share)

Where:

- "Total cohort MRR" is the sum of current MRR for all active customers in that cohort.

- "Top k" are the k customers with the highest current MRR in that cohort.

Optional formula (HHI)

If you want a single number that increases as revenue becomes more concentrated:

HHI is useful when your "whales" are not just one account—maybe it's four accounts that are each big.

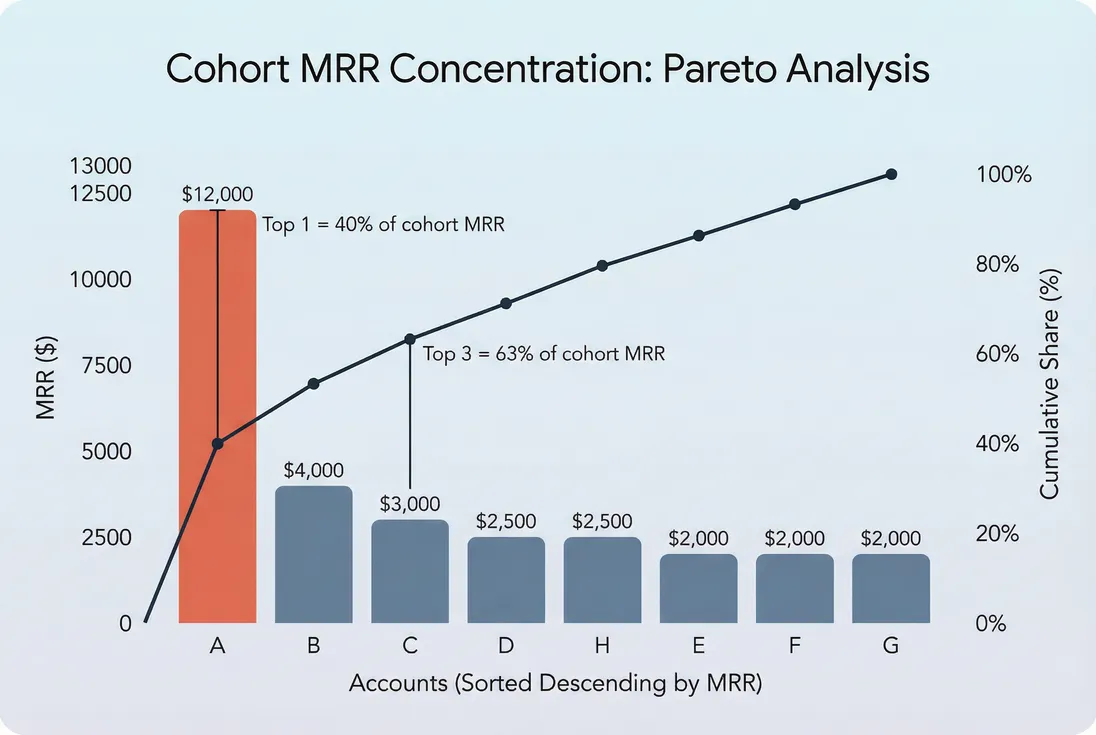

A concrete example

Assume your May cohort has 8 customers and current MRR looks like this:

| Customer | Current MRR | Share of cohort |

|---|---|---|

| A (whale) | $12,000 | 40% |

| B | $4,000 | 13% |

| C | $3,000 | 10% |

| D | $2,500 | 8% |

| E | $2,000 | 7% |

| F | $2,000 | 7% |

| G | $2,000 | 7% |

| H | $2,500 | 8% |

| Total | $30,000 | 100% |

- Top 1 whale risk = 40%

- Top 3 whale risk = (12k + 4k + 3k) / 30k = 63%

In practice, top-1 tells you "one renewal risk," while top-3 tells you "a small cluster risk."

A Pareto view shows whether you have one true whale or a small cluster driving the cohort.

What moves whale risk

A change in cohort whale risk is always caused by some combination of:

- Whale MRR changed (expansion, contraction, churn)

- Non-whale MRR changed (more churn in the tail, contraction, or new additions if your cohort definition includes late adds)

- The cohort mix changed (customers moved between cohorts due to data hygiene, mergers, or reclassification)

Here are the most common real-world drivers:

Whale expansion (good, but creates dependence)

A whale expanding can be your best growth lever—often reflected in Expansion MRR and stronger NRR (Net Revenue Retention). But it also increases cohort fragility.

You treat this as "good risk" when:

- Expansion is multi-threaded (multiple stakeholders, multiple teams using you)

- Contract terms are strong (multi-year, minimums, clear renewal dates)

- Product usage and value delivery are broad, not a single feature dependency

You treat it as "bad risk" when:

- Expansion is tied to one champion

- You're effectively customized for them (support and product risk)

- Renewal is tied to budget timing you can't control

Long-tail churn (often hidden)

Whale risk often rises because everyone else shrank, not because the whale grew.

That's why you should always look at whale risk next to:

- Logo Churn (are you losing lots of small customers?)

- Net MRR Churn Rate (is the tail shrinking net of expansion?)

- GRR (Gross Revenue Retention) (does the cohort hold revenue before expansion?)

If your tail is churning, whale risk will climb even if the whale is stable—an early warning that acquisition quality or onboarding is degrading.

Pricing and packaging step changes

Common pattern: you introduce a new "Pro" tier, annual prepay, or usage-based minimum that a subset of customers adopts. Those customers become whales inside the cohort.

This is not automatically wrong, but you should validate:

- Are you still landing enough "middle" accounts to reduce fragility?

- Are you creating a cliff where one account's downgrade creates a visible MRR drop?

Internal links that help this analysis:

Contract structure and timing

If you sell annual deals, whale risk becomes a renewal-calendar problem. A cohort can look stable for 10 months and then swing violently at renewal.

In those cases, pair cohort whale risk with:

- Average Contract Length (ACL)

- CMRR (Committed Monthly Recurring Revenue) (to understand what's actually committed)

The Founder's perspective

Whale risk is not just revenue risk. It is operating risk. A single whale can hijack roadmap, support, and incident response priorities. If you cannot say "no" to one customer, you should quantify how much of a cohort (or the company) you are effectively letting them control.

How to read it by cohort

The reason to track this by cohort (not just company-wide) is that cohorts encode the decisions you made at the time—pricing, targeting, messaging, onboarding, and sales process.

A practical interpretation framework

Use these three questions for each cohort:

Is concentration increasing or decreasing over time?

Increasing can be healthy if driven by expansion; unhealthy if driven by tail churn.Is the cohort outperforming on retention?

A whale-heavy cohort with weak retention is a double problem: you're both dependent and leaky.Is this pattern consistent across recent cohorts?

If only one cohort is whale-heavy, it may be one unusual deal.

If the last 3–4 cohorts are whale-heavy, it's a GTM shift.

"Acceptable" depends on your model

There is no universal benchmark, but you can use a rule-of-thumb table to decide how aggressively to manage it:

| Business motion | Top-1 cohort whale risk that starts to feel risky | Why |

|---|---|---|

| PLG / SMB | 10–15% | You need many small bets; one account shouldn't move the cohort. |

| Mid-market | 15–25% | Some concentration is normal; still want diversification. |

| Enterprise | 25–40%+ | Whales are expected; mitigate with renewal discipline and multi-threading. |

If you're unsure which motion you're actually running, look at ASP (Average Selling Price) and ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account) trends by cohort. Your data will tell you what you're becoming.

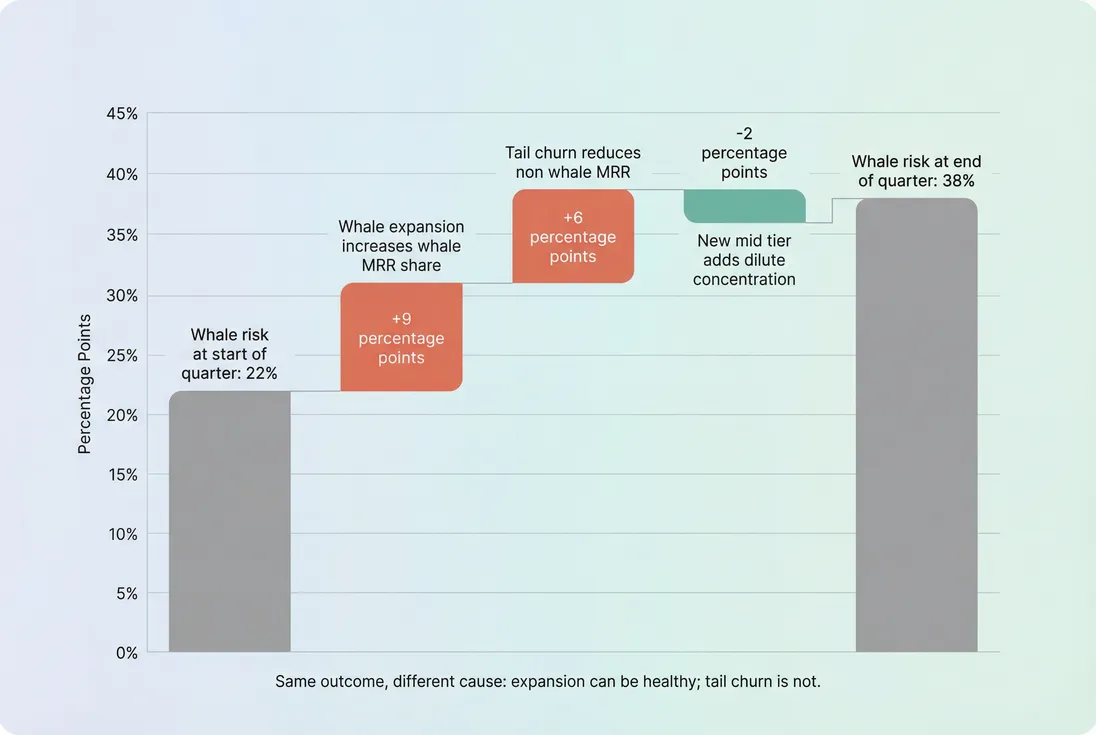

Diagnosing a spike in whale risk

When cohort whale risk jumps, don't guess. Break it into "whale moved" versus "tail moved."

A simple diagnostic checklist:

Did the whale expand?

Look for upgrades, added seats, add-ons—this is often a good story.Did the tail churn or contract?

Check whether a lot of small customers left. This usually points to onboarding, value delivery, or acquisition mismatch.Did the cohort definition change?

Data issues can create artificial spikes (e.g., customers reassigned to the wrong start month).

Always attribute the change: whale expansion and tail churn can produce the same whale-risk increase, but demand different decisions.

Why this attribution matters

- If whale risk rose due to expansion, your job is to de-risk renewal and delivery (commercial and customer success work).

- If whale risk rose due to tail churn, your job is to fix the machine (targeting, onboarding, activation, product value).

Pair this with your retention lens:

- Strong NRR (Net Revenue Retention) and stable GRR (Gross Revenue Retention) suggests the cohort is monetizing deeper.

- Weak GRR plus rising whale risk often means you're losing breadth and masking it with one account.

How founders use it

1) Forecast downside realistically

A whale-heavy cohort needs scenario planning. A simple approach:

- Base case: renew at current MRR

- Downside: whale churns or downgrades by 30–50%

- Mitigation: replacement pipeline required to offset the downside

This is where cohort whale risk becomes more actionable than generic growth rates: it tells you how big the hole is likely to be.

Tie it back to capital planning:

- If downside is large, reconsider hiring pace and marketing spend until renewal risk is managed.

- If you're fundraising, this feeds your narrative around risk controls (not just growth).

Related concept: Customer Concentration Risk

2) Set retention strategy by cohort shape

Whale-heavy cohorts require different retention mechanics:

- Executive sponsor mapping

- Multi-threading across teams and regions

- Product adoption beyond a single workflow

- Clear renewal timeline with mutual success criteria

Tail-heavy cohorts require:

- Onboarding completion improvements

- Faster time-to-value work

- Better lifecycle messaging and in-app education

If you treat both the same, you waste resources and miss the real failure mode.

3) Decide whether to lean into enterprise

A rising whale-risk pattern in new cohorts is often your business telling you the truth: you are landing bigger deals.

That can be a great path—but only if you accept the operating implications:

- More rigorous implementation

- Stronger SLAs and support expectations

- Longer sales cycles and more pipeline coverage needed

Use cohort whale risk alongside:

4) Fix acquisition quality before it shows up in churn

If whale risk rises because the tail is shrinking, it's often an early signal that:

- You're acquiring customers who never activate properly

- Your positioning pulled in the wrong segment

- Pricing is misaligned for smaller accounts

In that case, cohort whale risk is a leading indicator—telling you "this cohort will have retention issues" before the full churn wave hits.

Common mistakes

Only tracking company-wide concentration

You miss that new cohorts are fragile even if old cohorts are diversified.Celebrating whale expansion without de-risking renewal

Expansion creates dependency. Treat large expansions as a trigger for renewal planning, not just a revenue win.Ignoring contract timing

Annual renewals can create "cliff risk" that cohort whale risk highlights, but only if you review it ahead of renewal windows.Comparing cohorts with different definitions

Be consistent: "first paid month" versus "first touch" will change the cohort membership and the conclusion.

How to monitor it in practice

You don't need a complex model to operationalize cohort whale risk. You need consistency.

A lightweight monthly workflow:

- Pick your cohort basis (first paid month) and revenue basis (MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue)).

- For each cohort, list customers and current MRR, sort by MRR.

- Compute top-1 and top-3 shares.

- Investigate the biggest movers using MRR movement categories (expansion, contraction, churn).

If you're using GrowPanel, you can do most of the investigation quickly using cohorts, filters, the customer list, and MRR movements to isolate a cohort and see which accounts are driving the change. For product decisions, pair it with retention views to confirm whether concentration is masking broader churn.

Cohort whale risk is not a vanity metric. It's a fragility detector. Track it by cohort, attribute the changes, and you'll catch concentration bets early—while you still have time to diversify revenue or de-risk the whales you've earned.

Frequently asked questions

It depends on your go to market motion. SMB and product led cohorts often look healthiest when the top account is under 10 to 15 percent of cohort MRR. Mid market is often fine at 15 to 25 percent. Enterprise cohorts can exceed 30 percent, but you should pair that with strong renewal controls and multi year terms.

Not always. It can rise because a large customer expanded rapidly, which is usually good, especially if GRR and NRR remain strong. It is risky when whale risk rises because the long tail churned or contracted. Always decompose the change into whale expansion versus tail churn before reacting.

Customer concentration risk looks at your whole revenue base at once. Cohort whale risk isolates a single acquisition cohort, such as customers who first paid in March. That makes it a diagnostic for go to market changes. You can see if newer cohorts are increasingly fragile even if total company concentration looks stable.

First, verify the cause: a real enterprise land, a pricing step function, or a weak long tail. Then act: tighten renewal plans for the whale, reduce product or support single points of failure, and adjust acquisition to add more similar accounts or deliberately target more mid tier customers to balance the cohort.

Monthly is enough for most teams, and weekly during large enterprise ramps. Review it alongside MRR movements and retention so you can tell whether concentration is being created by expansion or by churn. Also review it before board meetings, fundraising, and annual planning because it changes downside scenarios.