Table of contents

Capital efficiency

Founders rarely run out of ideas—they run out of time and cash. Capital efficiency is the metric that tells you whether your growth engine converts cash into durable recurring revenue, or just turns spend into "activity" that looks good for a month and disappears the next.

Capital efficiency is how much net new recurring revenue you generate for each dollar of net cash you burn over a given period. Higher is better.

This is closely related to Burn Multiple, which flips the fraction.

If you remember one thing: capital efficiency is a "quality of growth" lens, not a vanity growth rate. It tells you whether you can scale without constantly needing more capital.

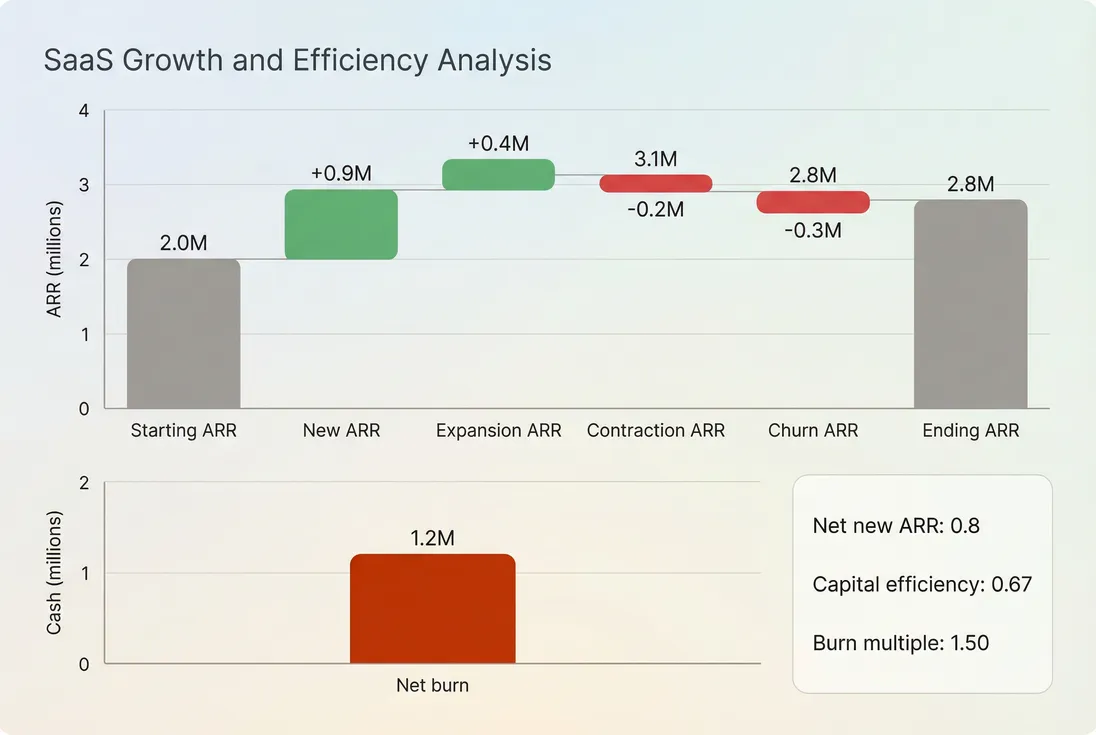

A simple way to "see" capital efficiency: net new ARR comes from new + expansion minus churn and contraction, then you compare it to net burn over the same period.

How to calculate it

You'll get a clean, decision-grade number only if you're consistent about two inputs:

- Net new ARR (the output)

- Net burn (the input cost)

Net new ARR: keep it movement-based

For most SaaS teams, the most practical approach is to compute net new ARR from ARR changes over the period.

If you operate in MRR, compute net new MRR first, then annualize:

Where does net new MRR come from? From recurring "movements":

- New MRR

- Expansion MRR

- Contraction MRR

- Churned MRR

- Reactivation MRR (optional, depending on your definition)

This is why movement reporting matters: it tells you why net new ARR changed, not just that it changed. If you need a refresher on recurring revenue definitions, start with MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue) and ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue). If you're using GrowPanel, the revenue-side components are typically visible in MRR movements.

Rule of thumb: capital efficiency is most actionable when net new ARR reflects durable recurring revenue, not one-time payments, professional services, or temporary discounting. (See Discounts in SaaS for common ways discounts distort your "growth" story.)

Net burn: use real cash, not vibes

Net burn should represent the net cash consumption of the business over the same period.

In practice, many founders approximate net burn as:

- Cash spend (payroll, tools, rent, ads, contractors, etc.)

- Minus cash collected from customers in that period

But be careful: annual prepayments can temporarily reduce net burn without improving the underlying model. If you sell annual upfront, your cash burn may look great while your unit economics are still weak. (This is also where Deferred Revenue becomes relevant.)

Use the same period for both

Common and useful cadences:

- Quarterly (best for B2B sales cycles)

- Monthly with smoothing (use T3MA (Trailing 3-Month Average) to reduce noise)

If you compute net new ARR for Q2, net burn must also be Q2. Mixing monthly burn with quarterly ARR deltas is the fastest way to confuse yourself and your board.

What this metric reveals

Capital efficiency answers one core question:

Is growth getting easier or harder to buy?

Two companies can grow ARR at the same percentage rate but have completely different capital efficiency because:

- One grows via expansion with high NRR (Net Revenue Retention).

- The other replaces churn with expensive new acquisition.

- One has short payback and high gross margin.

- The other has long payback, heavy discounting, or high COGS (Cost of Goods Sold).

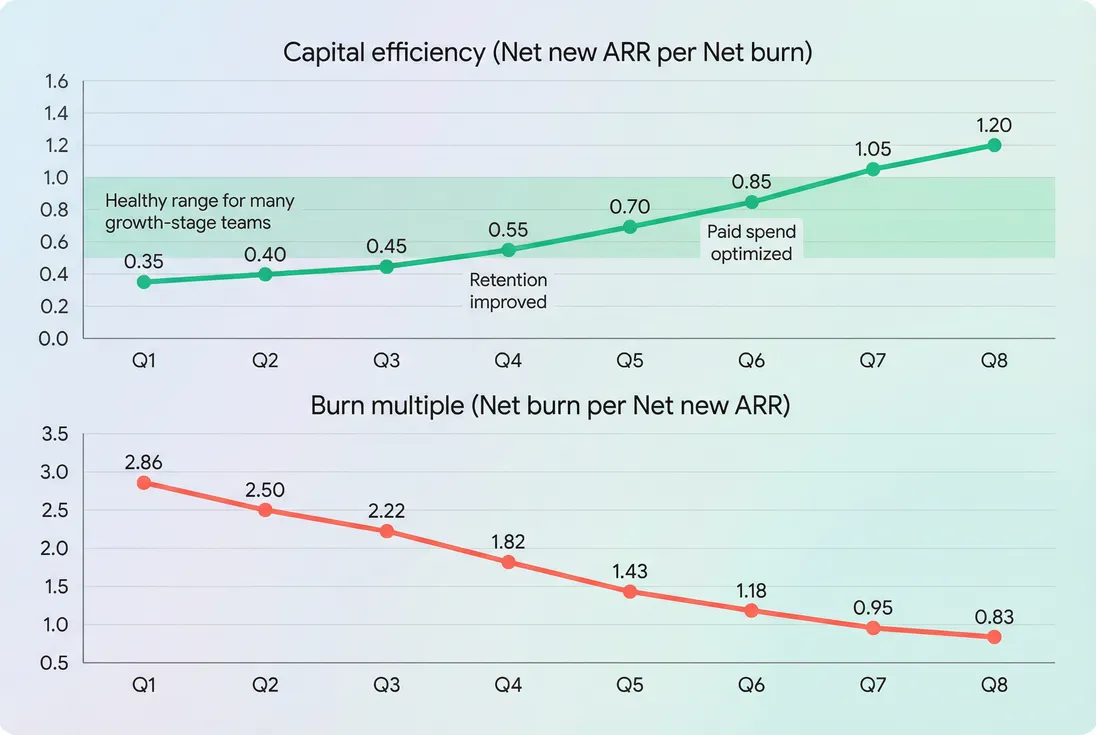

Interpreting changes over time

When capital efficiency rises, one (or more) of these is usually true:

- You improved retention: lower MRR Churn Rate or better GRR (Gross Revenue Retention)

- Expansion got stronger: higher Expansion MRR

- Acquisition got cheaper or more effective: better CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost) and conversion

- ARPA increased: better ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account) or higher ASP (Average Selling Price)

- Gross margin improved: you keep more of each dollar to reinvest

- Spend discipline improved: lower net burn without sabotaging pipeline

When capital efficiency falls, it's usually one of these patterns:

- You're buying growth with paid spend that hasn't proven payback yet

- Churn rose and you're "running to stand still"

- Your sales cycle lengthened, delaying ARR recognition while spend continues

- You expanded headcount faster than revenue productivity

The Founder's perspective

Capital efficiency isn't a judgment of whether you spent money. It's a read on whether your current plan is fundable—by revenue, by your existing runway, or by the next round. When it drops, the key question is whether it's a temporary investment dip or a broken growth loop.

What drives capital efficiency operationally

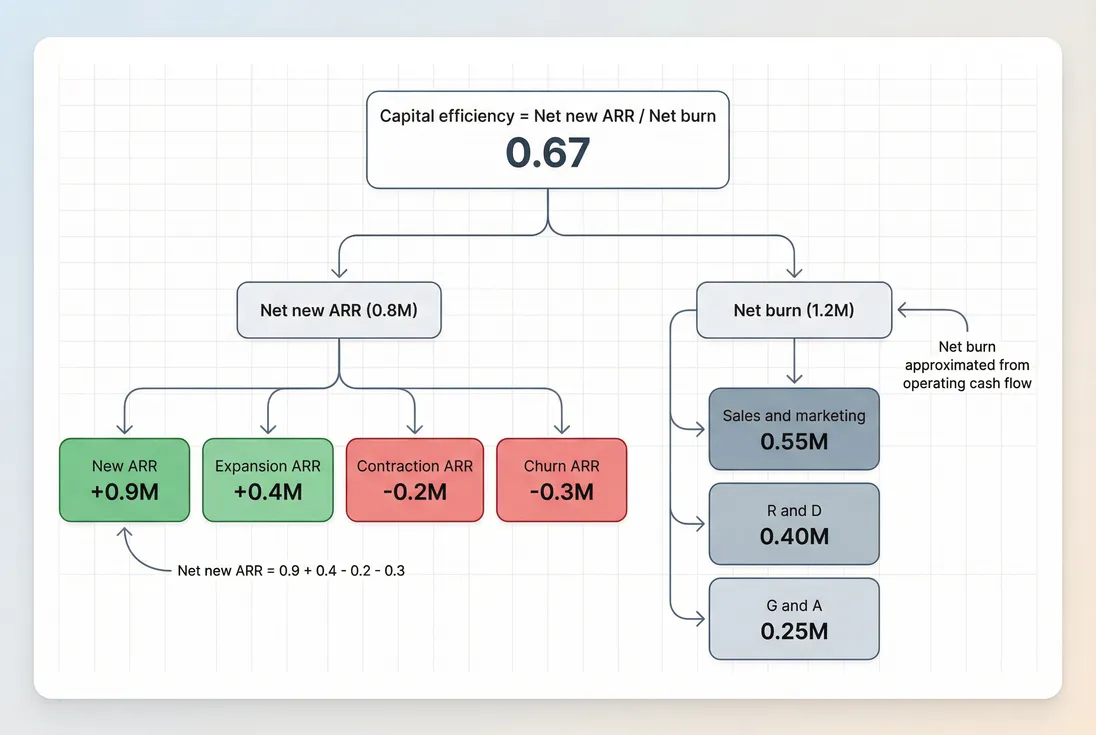

Treat capital efficiency like a diagnostic tree: net new ARR is the outcome of your go-to-market and retention system, while net burn is the cost of running that system.

A driver tree keeps the conversation specific: are you losing efficiency because churn rose, because new ARR slowed, or because burn stepped up ahead of results?

The revenue-side levers (net new ARR)

Capital efficiency improves fastest when retention and expansion do more of the work, because those dollars don't require the same incremental CAC and ramp time.

Key levers:

- Reduce churn and contraction. Start with Customer Churn Rate and Logo Churn, then look at revenue impact via Net MRR Churn Rate. If churn is concentrated, Churn Reason Analysis helps you fix the right problems.

- Increase expansion. Expansion is often a packaging, value delivery, and success motion problem. Expansion also depends on whether customers actually adopt your product—see Feature Adoption Rate and Time to Value (TTV).

- Improve new logo efficiency. Better targeting and conversion raise net new ARR without proportionally raising burn. Watch funnel health and sales execution metrics like Win Rate and Sales Cycle Length.

- Raise ARPA/ASP thoughtfully. Pricing and packaging can lift capital efficiency, but only if it doesn't spike churn. Pair changes with cohort monitoring using Cohort Analysis.

A practical mental model: if your churn rises, your capital efficiency almost always falls—even if top-line growth stays positive—because you're paying twice: once to acquire, again to replace.

The cost-side levers (net burn)

Net burn is not "bad." It's the price of growth. The question is whether burn is producing measurable leading indicators that reliably turn into ARR.

Levers founders control:

- Headcount ramp vs productivity. Hiring ahead of repeatable playbooks often tanks efficiency for 2–3 quarters. That can be fine—if you can explain the lag and track leading indicators (pipeline, activation, retention).

- Channel mix. If paid acquisition is rising faster than qualified pipeline, you're likely funding low-intent traffic. Tighten targeting, improve conversion, and pause what doesn't pay back.

- COGS and gross margin. Improving Gross Margin can increase how much growth you can "fund internally," even if net burn stays the same.

The Founder's perspective

When capital efficiency worsens, don't default to "cut spend." First ask: is spend increasing because we're scaling a proven motion, or because we haven't proven it yet? Cutting too early can lock in mediocrity; scaling too early can blow up runway.

How founders use it in real decisions

Capital efficiency becomes valuable when you tie it to decisions you'll make anyway: hiring, budgets, pricing, and fundraising.

1) Setting a hiring plan that respects runway

Runway math is simple; the hard part is knowing whether another dollar of burn produces enough ARR.

Use capital efficiency alongside:

Example: If your capital efficiency is 0.5, then each $1.0M of net burn tends to create about $0.5M of net new ARR. If you add $150k/month of burn for 6 months (about $0.9M), your plan should credibly produce about $0.45M net new ARR (or you should have a strong reason why it won't—yet).

2) Deciding whether to scale go-to-market

A common founder mistake is scaling go-to-market when new ARR looks good for a quarter, but retention isn't stable. Capital efficiency helps prevent that because churn and contraction directly subtract from net new ARR.

Before scaling, sanity-check:

- CAC Payback Period (is it short enough for your cash reality?)

- LTV:CAC Ratio (is lifetime value real or theoretical?)

- NRR (Net Revenue Retention) (does expansion reduce the need for constant new logo replacement?)

If your capital efficiency is improving because NRR improved, scaling is usually safer than if it improved due to a one-time spike in new logo sales.

3) Choosing pricing and discounting policies

Discounting can "buy" ARR growth at the expense of capital efficiency because it often:

- Lowers ARPA/ASP

- Attracts price-sensitive customers with higher churn risk

- Reduces expansion headroom

If you discount, be explicit about the trade: how much incremental ARR did you gain, and what happened to churn in the cohorts that received discounts? Pair Discounts in SaaS with cohort retention tracking.

4) Communicating with investors and your board

Investors like capital efficiency because it compresses a lot of reality into one number:

- Growth quality (net new ARR)

- Spend discipline (net burn)

- Retention durability (churn and contraction)

- Expansion power (upsell and usage growth)

But don't present it alone. Show the decomposition: new vs expansion vs churn, and what changed period-over-period. That's the difference between a number and a narrative.

Trends beat snapshots: improving efficiency over multiple quarters usually means retention, expansion, and acquisition efficiency are compounding.

Benchmarks and context that matter

Capital efficiency benchmarks vary by stage and motion. Here's a practical translation between capital efficiency and burn multiple (since many boards use burn multiple language).

| Capital efficiency (higher better) | Equivalent burn multiple (lower better) | Practical read |

|---|---|---|

| 1.25 | 0.80 | Excellent: growth is cheap relative to burn |

| 1.00 | 1.00 | Strong: close to "$1 burn for $1 ARR" |

| 0.67 | 1.50 | Good: common in healthy scaling phases |

| 0.50 | 2.00 | Okay: watch retention and payback closely |

| 0.33 | 3.00 | Concerning: likely inefficient GTM or churn |

| 0.25 | 4.00 | Critical: runway risk unless changing fast |

Stage-specific expectations

- Pre-product-market fit: capital efficiency can be low because burn is funding learning. Still, track it to ensure you're not scaling spend before you have retention signals.

- Early go-to-market (seed to early Series A): expect volatility. Use quarterly measurement and explain outliers (e.g., enterprise deal timing).

- Scaling (Series A to B and beyond): investors expect improving efficiency as playbooks repeat. If it deteriorates, you need a clear causal story (new segment, new product line, intentional headcount ramp).

Motion-specific distortions

- Enterprise sales: long cycles and lumpy closes can whipsaw net new ARR quarter to quarter. Use smoothing and look at pipeline leading indicators, but don't ignore churn risk in large accounts (see Customer Concentration Risk).

- Product-led growth: spend may show up more in R&D than S&M, but the math still applies. If activation and retention are weak, PLG can burn quietly for a long time.

- Usage-based pricing: ARR may lag usage adoption, and revenue recognition can be nuanced. Be clear about what you treat as recurring and how you estimate ARR (see Usage-Based Pricing).

When capital efficiency "breaks" (and what to do)

A few common failure modes show up across SaaS companies:

You're growing, but efficiency is falling

This usually means new sales are masking churn or contraction. Fix by:

- Segment churn by customer type and acquisition source

- Improve onboarding and value delivery (see Onboarding Completion Rate and Time to Value (TTV))

- Revisit ideal customer profile and disqualify poor-fit deals earlier

Efficiency looks great, but it's an illusion

Common causes:

- Annual prepay boosted cash collections, reducing net burn

- One-time invoice timing made ARR change look bigger than it is

- Discounts pulled forward demand with worse cohorts later

Mitigation: separate cash story from ARR story. Track Free Cash Flow (FCF) and ARR movements side by side, and validate cohort retention.

Net new ARR is near zero

Capital efficiency becomes noisy or meaningless when net new ARR is tiny (or negative). In those periods, stop obsessing over the ratio and focus on the drivers:

- Are you losing accounts (logo churn) or dollars (net MRR churn)?

- Is pipeline drying up, or is conversion broken?

- Are you overstaffed for the current revenue base?

If net new ARR is negative, the ratio flips into a warning siren: you're burning cash while shrinking. The priority becomes stopping the leak (retention and contraction) before scaling acquisition.

A practical operating cadence

If you want capital efficiency to change decisions (not just appear in a deck), use a simple monthly or quarterly routine:

- Compute capital efficiency for the period (and a trailing 3-month average)

- Decompose net new ARR into new, expansion, churn, contraction

- Explain net burn changes (headcount, paid spend, infrastructure, one-time costs)

- Pick one improvement bet for the next period (retention, pricing, conversion, channel mix)

- Validate in cohorts using Cohort Analysis so you don't confuse short-term wins with long-term value

The Founder's perspective

The goal isn't to maximize capital efficiency at all costs. The goal is to know what efficiency you're buying, why it changed, and whether your runway supports the lag between investment and ARR. If you can explain that clearly, you'll run the company better—and fundraise from a position of control.

Frequently asked questions

They are the same relationship expressed in opposite directions. Capital efficiency is net new ARR per dollar of net burn, so higher is better. Burn multiple is net burn per dollar of net new ARR, so lower is better. Use one consistently and benchmark against your stage and go to market motion.

As a rough guide, capital efficiency above 1.0 is strong, around 0.5 is acceptable for many growth-stage teams, and below 0.3 usually signals a go-to-market or retention problem. Earlier stages can be temporarily lower while building product. Always check trends over trailing 3 to 6 months.

Quarterly is usually more reliable because sales cycles, invoicing timing, and churn events can distort monthly results. Many teams track it monthly using a trailing 3-month average to smooth volatility. The key is matching net burn and net new ARR to the same period and using consistent ARR rules.

The most common distortions are counting cash collections instead of ARR, including annual prepayments as growth, or ignoring churn that will hit in the next month. Cost deferrals can also temporarily reduce burn. Use ARR or MRR movements for the revenue side, and true net cash burn for the spend side.

Start by improving retention and expansion so each new customer adds more durable ARR. Then reduce payback time by tightening targeting, improving conversion, and raising ARPA through packaging and pricing. On the cost side, cut low-performing channels and slow headcount in functions that do not directly improve acquisition, activation, retention, or gross margin.