Table of contents

Burn multiple

Founders don't run out of ideas—they run out of cash. Burn multiple is the metric that tells you whether your growth is worth the cash you're consuming, in a way that's easy to compare across months, quarters, and even companies.

Burn multiple is the amount of net cash you burn to generate one dollar of net new ARR in the same period.

Lower is better. A burn multiple of 1.5 means you burned $1.50 to add $1.00 of ARR.

Tracking net burn and net new ARR together makes it obvious whether growth is getting more or less capital efficient—not just bigger.

What burn multiple tells you

Burn multiple is a practical measure of capital efficiency: how effectively you convert cash into durable recurring revenue. It's most useful when you're making decisions like:

- Can we hire 3 more AEs right now, or do we need to fix conversion first?

- Are we scaling spend faster than our ability to convert leads and retain customers?

- If fundraising gets harder, do we have an efficiency story (or only a growth story)?

This is why burn multiple often shows up in board decks alongside Burn rate, Runway, and Capital Efficiency. Growth alone can be bought. Efficient growth is harder—and more defensible.

The Founder's perspective: A "good" burn multiple isn't about impressing investors. It's about knowing whether the next dollar you spend is likely to come back as durable ARR before you run out of time (runway).

What it is (and isn't)

Burn multiple is not a profitability metric. You can have a great burn multiple and still be unprofitable (common in growth phases). It's also not a pure sales metric like SaaS Magic Number—it captures the whole company's cash usage relative to ARR growth.

Burn multiple is best treated as a system metric. If it worsens, the root cause could be marketing efficiency, sales cycle length, onboarding, support load, product reliability, or churn.

How to calculate it cleanly

A clean calculation depends on two inputs: net burn and net new ARR, measured over the same period (month or quarter).

Step 1: define net burn

Most teams use net cash burn—effectively negative Free Cash Flow (FCF):

- Cash in from customers (collections)

- minus cash out for payroll, vendors, hosting, tools, etc.

- minus capital expenditures (if meaningful for you)

Avoid mixing in financing flows (fundraising, loan proceeds) because that's not "burn," it's how you fund burn.

If you only have a P&L handy, you can approximate from operating loss, but that can mislead due to non-cash expenses and working capital swings. If you do use an approximation, be consistent and label it.

Step 2: define net new ARR

Net new ARR is simply the change in recurring revenue run-rate during the period.

If you track MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue) instead, you can annualize:

Important: use recurring revenue. Exclude one-time services, implementation fees, and other non-recurring items (see One Time Payments).

Step 3: calculate burn multiple

Example (quarterly):

- Net burn: $900,000

- ARR start: $2.4M

- ARR end: $3.0M

- Net new ARR: $600,000

Burn multiple = 900,000 / 600,000 = 1.5x

What "period" should you use?

- Monthly is responsive but noisy (timing of collections, commissions, annual invoices).

- Quarterly is usually more decision-useful for hiring and spend.

- If you have volatility, consider a trailing average like T3MA (Trailing 3-Month Average) for both burn and net new ARR.

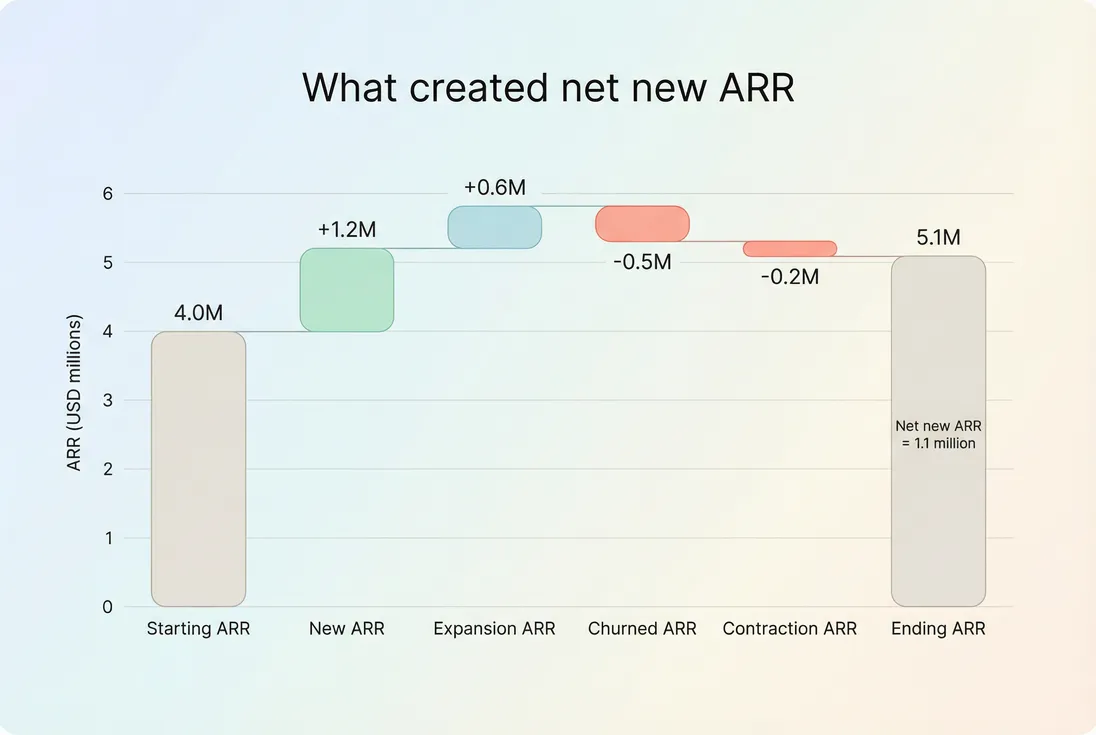

Sanity-check net new ARR with movements

Net new ARR is the net of several forces: new sales, expansion, churn, contraction, and reactivation. If your burn multiple moves suddenly, you want to see which driver changed.

If you use GrowPanel, you can validate the "why" behind net new ARR by checking ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue) and drilling into the underlying MRR movements using filters.

Net new ARR is not just new sales. Retention and expansion can swing burn multiple as much as pipeline does.

What drives burn multiple

Burn multiple moves for only two mathematical reasons: burn changes or net new ARR changes. Operationally, that maps to a handful of real levers.

1) Growth quality (retention and expansion)

A company with strong retention can keep net new ARR high even without massive new logo volume. A company with weak retention needs constant replacement growth just to stand still.

Track burn multiple alongside:

- NRR (Net Revenue Retention) and GRR (Gross Revenue Retention)

- Net MRR Churn Rate and Logo Churn

- Expansion MRR and Contraction MRR

If burn multiple worsens while pipeline looks stable, churn is often the silent culprit.

The Founder's perspective: If retention is weak, "spending more on acquisition" usually makes burn multiple worse, not better. You're pouring water into a leaky bucket faster.

2) Gross margin and COGS creep

Burn multiple uses cash burn, so hosting costs, support load, and services-heavy onboarding matter. If COGS (Cost of Goods Sold) rises or Gross Margin falls, burn tends to rise even if ARR growth holds.

Common margin-related causes of burn multiple deterioration:

- Enterprise deals that require heavy support or custom work

- Usage-based infrastructure costs scaling faster than pricing

- Growing a services component that isn't priced appropriately

3) Go-to-market efficiency and payback

Even if you don't compute burn multiple from CAC directly, CAC dynamics show up inside it.

If you lengthen your sales cycle, cut win rate, or over-hire before ramp, burn rises immediately while ARR lags—burn multiple spikes.

Pair it with:

4) Pricing and discounting discipline

Pricing changes can improve burn multiple without changing headcount—because net new ARR rises faster than burn.

But the reverse is also true: heavy discounting increases "ARR effort" per deal and can quietly worsen burn multiple.

Useful references:

5) Collections timing and billing mechanics

Burn multiple is partly a cash metric. If collections improve, net burn can look better even if underlying unit economics haven't changed.

Watch out for:

- Annual upfront billing (cash in now, ARR recognized over time)

- Refunds and disputes (see Refunds in SaaS and Chargebacks in SaaS)

- Payment processing drag (see Billing Fees)

- Receivables risk (see Accounts Receivable (AR) Aging)

Benchmarks and interpretation

Burn multiple is context-dependent: stage, growth rate, margins, and go-to-market model all matter. Still, ranges can help you decide whether to push, fix, or pause.

Practical benchmark ranges

| Burn multiple (x) | Typical interpretation | Common founder action |

|---|---|---|

| < 1.0 | Exceptionally efficient | Consider accelerating if retention is strong and pipeline is real |

| 1.0–2.0 | Strong / healthy | Scale selectively; keep an eye on payback and churn |

| 2.0–3.0 | Okay but needs scrutiny | Diagnose: is it ramp costs, churn, or pricing pressure? |

| 3.0–5.0 | Inefficient | Slow hiring; fix retention, ICP, funnel conversion, or margin |

| > 5.0 | Usually broken or unsustainable | Re-plan: reduce burn, reset GTM, or correct measurement errors |

Stage nuance (rule of thumb, not law):

- Pre-product-market fit: burn multiple is often not stable; focus on learning velocity and retention signals.

- Early repeatability (seed/early A): 2–5 is common, but you want a path downward.

- Scaling (A/B): you typically want 1–2 with improving trend.

- Late-stage: expectations tighten; durable businesses often operate near or below 1.

How to read changes over time

When burn multiple changes, avoid debating the number—decompose it:

- Did net burn change?

- Hiring wave, tooling, agency spend, infrastructure, support load

- Did net new ARR change?

- New logo volume, expansion, churn, contraction, reactivations

A useful habit: whenever burn multiple worsens, force a "two-line explanation":

- "Burn rose because ___"

- "Net new ARR fell because ___"

If you can't answer both quickly, you're not instrumented enough yet.

How founders act on it

Burn multiple becomes powerful when you use it to make specific operating calls—not just to report performance.

Budgeting and hiring

Burn multiple is a guardrail against scaling headcount faster than revenue capacity.

Example policy:

- If burn multiple is trending down (improving) for 2–3 quarters, open up hiring in the bottleneck function.

- If it spikes, freeze non-essential hiring until you identify whether the issue is churn, conversion, or ramp.

This complements runway planning from Runway because it connects "how long we last" to "how effectively we grow."

The Founder's perspective: Hiring is a one-way door in the short term. Burn multiple helps you avoid hiring into a funnel problem that should have been fixed with positioning, onboarding, or retention work.

Fundraising narrative (without spinning)

Investors use burn multiple to answer: "Is this team disciplined, and is growth repeatable?"

A strong story is usually:

- Burn multiple is improving

- Retention is healthy (NRR/GRR)

- Payback is reasonable

- Growth is not purely discount-driven

Pair burn multiple with Rule of 40 for a fuller view (efficiency plus profitability trajectory).

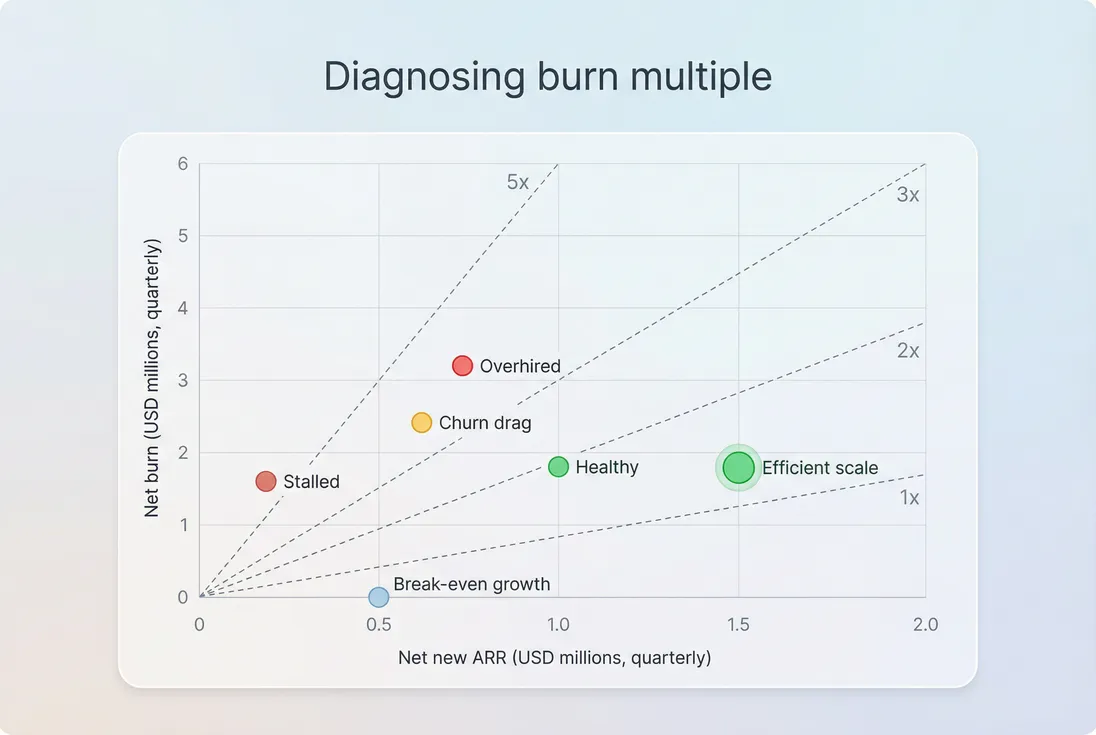

Diagnosing "where the leak is"

This diagnostic chart makes burn multiple more actionable: plot net burn vs net new ARR and overlay lines of constant burn multiple.

The same burn multiple can come from very different realities—this view helps separate "overburn" from "not enough ARR growth."

Use this to drive the next question:

- If you're "overhired," your fastest fix might be slowing hiring and improving ramp productivity.

- If you're "churn drag," the fix is often onboarding, product value, and customer success—paired with churn analysis (see Churn Reason Analysis).

When the metric breaks (and how to handle it)

Burn multiple can mislead when cash timing and ARR timing diverge. Common cases:

- Annual prepay-heavy businesses: cash collections improve burn without changing underlying efficiency.

- Quarter with one large enterprise deal: net new ARR jumps; burn multiple looks amazing; don't extrapolate.

- High refunds/chargebacks month: net burn looks worse; treat as an anomaly and track separately.

- Usage-based pricing ramp: ARR may lag usage growth; consider using CMRR (Committed Monthly Recurring Revenue) until pricing stabilizes.

- Major product rebuild: burn rises before ARR impact; treat as an intentional investment and track milestones.

Practical mitigations:

- Use quarterly periods (or trailing averages)

- Add notes for one-time events

- Pair with retention and payback metrics so you don't "optimize" the wrong thing

A practical playbook to improve it

Improving burn multiple means improving either side of the fraction:

- Reduce net burn (without damaging the engine)

- Increase net new ARR (without buying low-quality growth)

Here are moves that typically work in real SaaS operators' hands:

Improve net new ARR first (usually higher leverage)

- Tighten ICP and qualification to raise win rate and reduce support burden later (see Qualified Pipeline).

- Reduce time-to-value and onboarding friction (see Time to Value (TTV) and Onboarding Completion Rate).

- Address churn systematically (see Customer Churn Rate and Voluntary Churn).

- Drive expansion with clearer packaging, seat growth paths, and value-based pricing (see Per-Seat Pricing and Usage-Based Pricing).

Reduce burn in ways that preserve growth capacity

- Cut spend that doesn't connect to pipeline or retention (vanity channels, redundant tools).

- Fix gross margin issues (infrastructure efficiency, support processes) before cutting acquisition.

- Pace hiring to ramp reality; use productivity metrics (see Revenue per Employee).

Don't "game" the metric

Founders sometimes improve burn multiple by:

- Pausing acquisition (net new ARR drops next quarter)

- Discounting aggressively to close deals (retention suffers later)

- Counting non-recurring revenue as ARR (the number lies)

A burn multiple that improves while churn worsens is not a win—it's a delayed problem.

Quick operating checklist

If you review burn multiple monthly or quarterly, ask:

- Did net burn change? Why (headcount, infra, tooling, collections)?

- Did net new ARR change? Why (new, expansion, churn, contraction)?

- Is retention stable enough that new ARR will stick?

- Are we hiring into a conversion problem or scaling something repeatable?

Used this way, burn multiple becomes less about reporting efficiency—and more about protecting your company's ability to keep making bets long enough to win.

Frequently asked questions

For seed-stage companies still proving a repeatable go-to-market, burn multiples often land around 2 to 5. Below 2 is strong if growth quality is real (low churn, durable expansion). Above 5 usually means you are scaling spend ahead of traction or measuring net new ARR incorrectly.

Use net new ARR (or annualized net new MRR) because burn multiple is about efficiently building recurring revenue capacity, not recognizing revenue. Revenue can be distorted by annual prepayments, services, or timing. If you cannot measure ARR cleanly, use CMRR as a practical proxy.

A negative burn multiple typically means you are not burning cash (you generated cash) while still adding ARR. That can happen with strong gross margins, efficient acquisition, annual prepayments, or reduced expenses. Validate it is not a timing artifact in cash collection or deferred expenses.

Upfront annual payments can make burn look artificially low (or even negative) because cash comes in before the ARR is "earned" over time. To avoid false optimism, calculate burn using true net cash burn and sanity-check with operating trends. Some teams also track a trailing average for stability.

Improve it by increasing net new ARR per dollar spent, not by cutting indiscriminately. The highest-leverage moves are reducing churn, driving expansion, shortening sales cycles, tightening ICP focus, and fixing onboarding. Pair burn multiple with CAC payback and retention metrics to avoid "efficient" but fragile growth.