Table of contents

ARPA (average revenue per account)

Most SaaS teams can tell you whether revenue is up. Fewer can tell you whether the average customer you're acquiring is getting more valuable over time—and whether growth is coming from better monetization or just more volume. ARPA is one of the fastest ways to see that.

ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account) is the average recurring revenue you generate per active customer account in a given period (usually monthly). It answers: On average, how much is each account worth right now?

It's easy to confuse ARPA with AR (accounts receivable). If you're looking for billing collection metrics, see Accounts Receivable (AR) Aging. ARPA is about recurring monetization, not receivables.

What ARPA reveals

ARPA is a blunt average, but it's extremely useful because it compresses several business realities into one number:

Pricing and packaging effectiveness

If ARPA rises after packaging changes, you likely improved your ability to capture value (assuming churn doesn't spike later).Customer mix and "quality of growth"

If your new customers are consistently smaller than your existing base, ARPA will drift down over time—even if logo growth looks great. That usually shows up later as weaker CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost) payback and lower LTV (Customer Lifetime Value).Expansion motion strength

Healthy B2B SaaS often relies on expansions (seats, usage, add-ons). When expansions dominate, ARPA tends to climb even if new logo volume slows. Pair ARPA with Expansion MRR and NRR (Net Revenue Retention).Churn mix (who you're losing)

ARPA can go up because you churned a lot of low-paying customers. That might be fine (intentional move upmarket) or a warning (your low end is failing, and your funnel might be next).

The Founder's perspective

ARPA is the quickest sanity check on whether you're building a bigger business or just running faster. If ARPA is flat while your costs rise, you're signing up more accounts but not increasing the economic value of each relationship.

ARPA vs nearby metrics

Founders often swap these terms casually, but they answer different questions:

- ARPA: revenue per account (best for B2B and "customer company" views).

- ARPU: revenue per user (depends on clean user counts and user definitions).

- ASP (Average Selling Price): average price of what you sold (often deal-level, useful for sales performance). See ASP (Average Selling Price).

- ACV (Annual Contract Value): annualized contract value, commonly used in sales-led SaaS. See ACV (Annual Contract Value).

How to calculate ARPA

At its simplest, ARPA is recurring revenue divided by the number of active accounts.

If you prefer an annualized view:

Where:

- MRR is your MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue) for the period (after discounts, normalized across billing intervals).

- ARR is ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue).

- Active accounts should be the count of customers with an active subscription in the period (you must define exactly what "active" means).

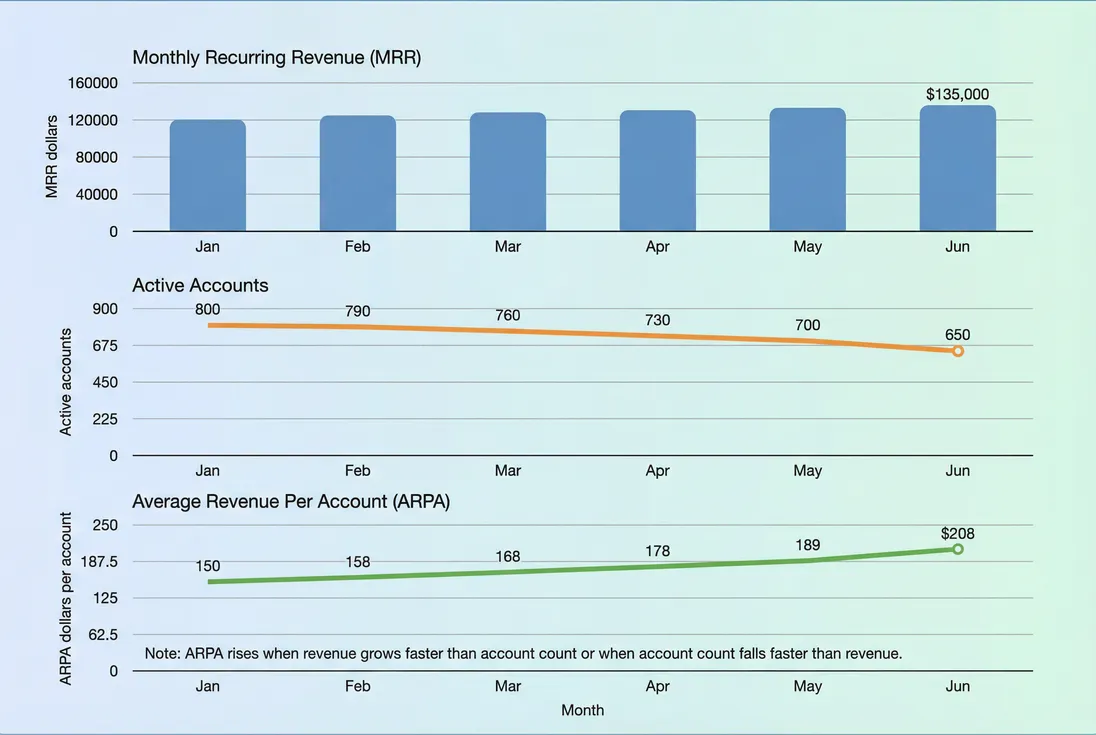

A concrete example

Say you end March with:

- MRR = $128,000

- Active accounts = 760

So ARPA is about $168 per account per month.

Define your denominator carefully

Small definition differences create big ARPA swings. Decide and document:

- Do trials count? Usually no, unless trials are paid and treated as subscriptions.

- Do paused accounts count? Typically no, if they're not paying.

- What about delinquent accounts? If they're still considered active in billing, be consistent. If you remove them, ARPA may look artificially higher.

If you're tracking "active customer count" elsewhere, align your definitions with Active Customer Count.

Keep the numerator "recurring"

ARPA is most useful when it reflects durable subscription value, so avoid contaminating it with non-recurring noise:

- Exclude one-time services unless you're explicitly analyzing total revenue per account. See One Time Payments.

- Treat discounts as real reductions in recurring value. See Discounts in SaaS.

- Handle refunds consistently. See Refunds in SaaS.

- If you collect VAT/GST, don't treat tax as revenue. See VAT handling for SaaS.

What moves ARPA up or down

ARPA changes when either revenue changes or active accounts change. That sounds obvious—until you're staring at a dashboard wondering why ARPA moved.

Here are the most common drivers, and what they usually mean operationally.

Pricing and packaging

ARPA up can come from:

- List price increases

- Packaging that nudges customers to higher tiers

- Removing steep legacy discounts

- Introducing add-ons that attach well

ARPA down can come from:

- Aggressive discounting to hit growth targets

- Launching a low-price plan that becomes your dominant acquisition path

- Competitive pressure forcing price concessions

Practical check: if ARPA rises, validate that churn doesn't worsen in 30–90 days (especially on monthly plans). Use Customer Churn Rate and Logo Churn to confirm you didn't "buy" ARPA by pushing customers out.

Customer mix shift

ARPA can move even if nothing changed for any single customer.

Example: You add 200 new $49 accounts and only 10 new $2,000 accounts this month. Your business may still be growing, but your average account value will drift down.

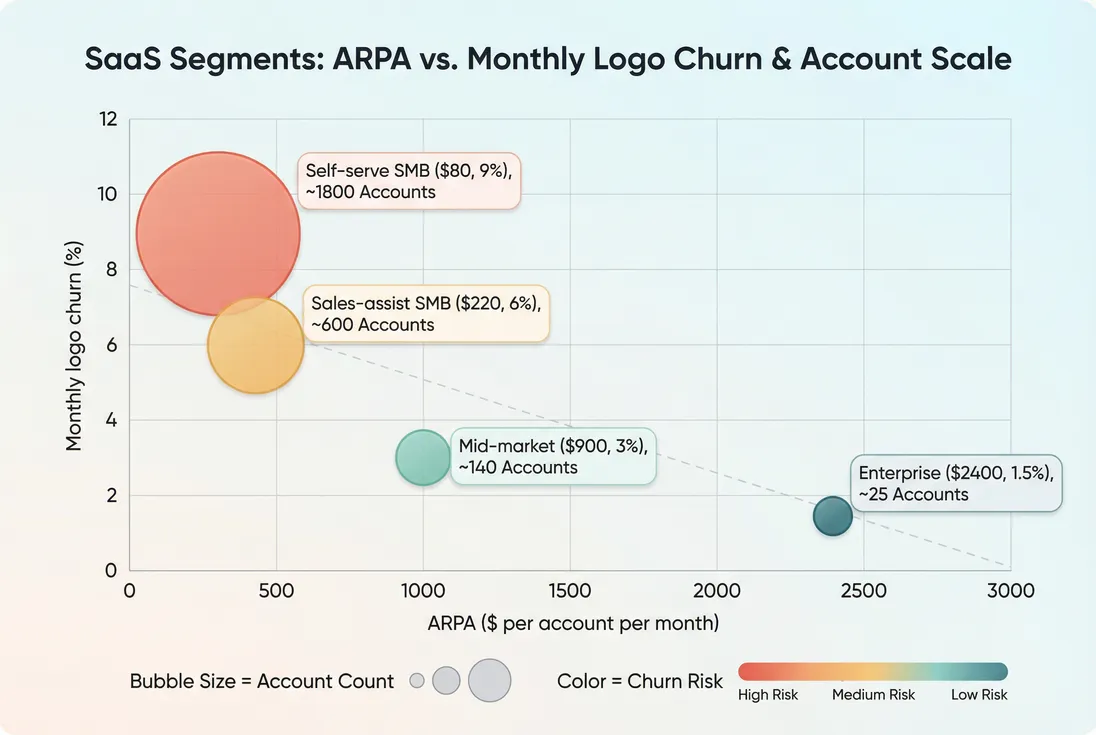

This is why ARPA is much more actionable when segmented by:

- Plan/tier

- Acquisition channel

- Company size proxy (if you have it)

- Region or currency

- Sales motion (self-serve vs sales-led)

Segmentation is also how you avoid "average traps" (more on that below). Cohorts help here too—see Cohort Analysis.

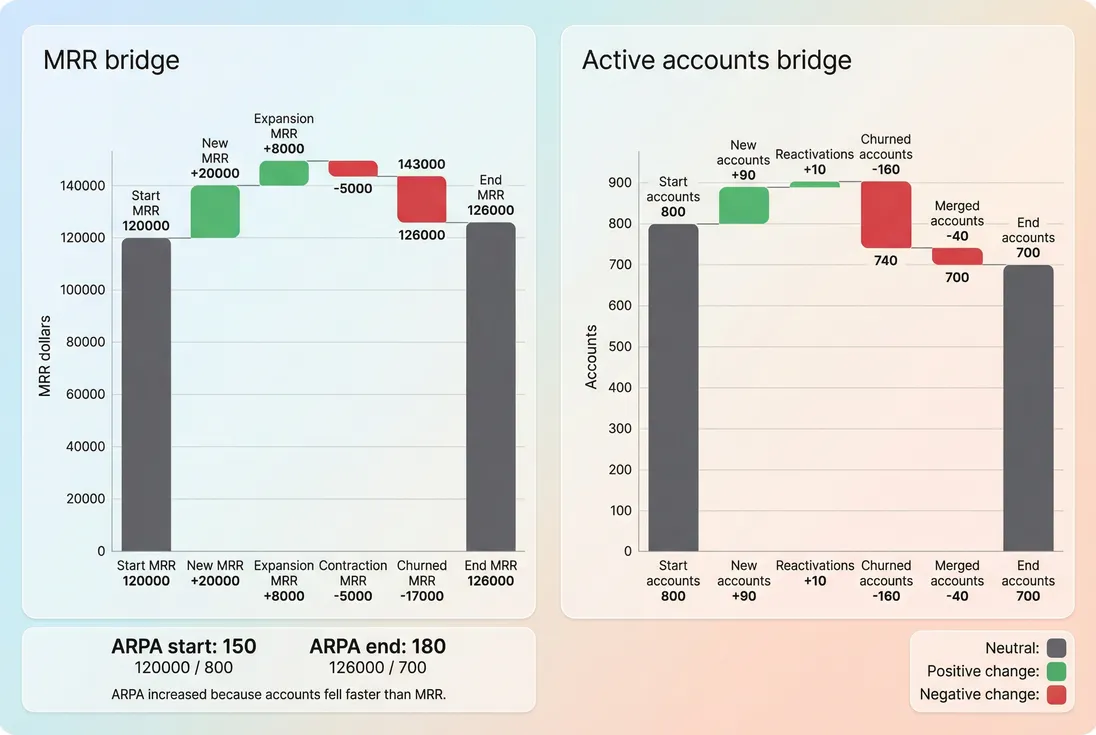

Expansion and contraction dynamics

In account-based SaaS, ARPA is a summary of your land-and-expand engine:

- Expansions (more seats, add-ons, usage) push ARPA up.

- Contractions (downgrades, seat reductions) push ARPA down.

- If your churn is stable but ARPA is falling, contractions are often the culprit.

To debug, pair ARPA with:

Churn changes the average

This is where founders often misread ARPA.

If you lose a lot of low-paying customers:

- Active accounts fall a lot

- MRR falls a little

- ARPA goes up

That does not automatically mean your business improved. It might mean:

- Your low-end onboarding is broken

- Your low-end product-market fit is weak

- Your support burden is forcing low-end customers out

- Or you're intentionally moving upmarket (which can be good)

You need to validate intent with retention metrics like GRR (Gross Revenue Retention) and NRR (Net Revenue Retention).

A quick "ARPA driver" cheat sheet

| What happened | ARPA likely goes | What to check next |

|---|---|---|

| Price increase on renewals | Up | Churn by cohort 30–90 days later |

| Heavy discounting to close deals | Down | CAC Payback Period and expansion rates |

| Enterprise deals become larger share | Up | Customer Concentration Risk |

| Low-end customers churn | Up (sometimes) | Logo Churn and reasons |

| Seat downsells | Down | Adoption, value realization, renewal risk |

| New low-price plan takes off | Down | Upgrade path, support load, margins |

How founders use ARPA in real decisions

ARPA becomes powerful when it's tied to decisions with a clear "if this, then that."

1) Forecasting: growth as accounts times ARPA

At a high level, your recurring revenue can be approximated as:

That's not an accounting identity in every edge case, but it's a practical forecasting mental model. It forces clarity on which lever you're actually pulling:

- Are you growing by adding accounts?

- Or by increasing revenue per account (pricing, expansion, mix)?

If your plan assumes ARPA will rise, you should be able to name the mechanism (seat growth, add-ons, tier upgrades) and when it happens in the customer lifecycle.

2) Choosing a go-to-market motion

ARPA is one of the cleanest signals of whether you can support a sales-led approach.

If ARPA is $30–$80/month, a high-touch sales motion is usually hard to justify unless:

- sales cycles are extremely short, or

- expansion is highly reliable, or

- you're selling annually upfront with strong retention.

If ARPA is $800–$2,000+/month, you can often afford:

- more human onboarding,

- account management,

- and a more consultative sale—if churn stays controlled.

Tie this back to efficiency metrics like SaaS Magic Number and capital constraints like Burn Rate.

The Founder's perspective

ARPA tells you what kind of company you're building: a volume business, an expansion business, or an enterprise relationship business. Your hiring plan (support, sales, success) should match that reality, not the story you tell yourself.

3) Setting pricing priorities

ARPA helps you evaluate whether pricing work is worth doing now.

A rule of thumb: pricing work matters most when either:

- you have stable retention (so price improvements stick), or

- you're clearly under-monetized relative to delivered value.

If ARPA is stagnant while usage and perceived value are rising, you're likely leaving money on the table. If ARPA is rising but churn is worsening, your value delivery isn't keeping pace with monetization.

For usage-driven products, also consider Usage-Based Pricing and whether your ARPA trend is really a usage trend.

4) Improving LTV and payback

Many LTV approximations are driven heavily by revenue per account. If ARPA increases without harming retention, LTV usually improves.

This is why ARPA is frequently reviewed alongside:

The important nuance: ARPA only helps LTV if it's durable. A temporary ARPA lift from one-time upgrades or short-term discount roll-offs won't help if churn rises.

5) Operationalizing segmentation (where ARPA earns its keep)

One overall ARPA number is rarely enough to run the business. The most useful ARPA views are segmented:

- New customers' ARPA vs existing customers' ARPA

- ARPA by plan/tier

- ARPA by acquisition channel

- ARPA by geo/currency

- ARPA by cohort start month (to see if newer cohorts are weaker)

If you're using GrowPanel, ARPA is easiest to interpret when you slice it using Filters and then validate outliers in the Customer List. For the metric definition and display, see ARPA.

Where ARPA breaks (and how to protect yourself)

ARPA is useful, but it's also easy to misinterpret. These are the common failure modes.

Averages hide distribution

Two companies can both have $500 ARPA:

- Company A: most accounts at $450–$550 (stable, predictable)

- Company B: 95% of accounts at $100 and a few whales at $20,000 (fragile)

If whales dominate, you may have serious Customer Concentration Risk even while ARPA looks healthy.

Practical fix: review ARPA alongside a customer revenue distribution (or at least top-10 customers' share of MRR).

ARPA can "improve" from churn

If ARPA rises while:

- Logo Churn rises, or

- new customer volume declines, or

- support tickets spike,

then the ARPA lift may be a symptom of the low end falling out—not stronger monetization.

Short periods create noise

ARPA is a ratio. When your account base is small, a few upgrades or churn events can swing ARPA dramatically.

Practical fix: track ARPA using a smoother view (like a trailing average) and always pair it with absolute counts (MRR and active accounts).

Billing artifacts and revenue definitions

ARPA should be consistent with how you treat:

- annual prepay normalization into MRR,

- mid-cycle proration,

- credits/refunds,

- fees or pass-through charges.

If definitions change, ARPA trendlines become unreliable for decision-making. When you make a definition change, annotate the time series so you don't "learn" the wrong lesson.

ARPA isn't a product value metric

ARPA measures monetization, not necessarily value delivery. You can increase ARPA while product adoption declines (customers paying but disengaging), which later converts into churn or contraction.

Pair ARPA reviews with leading indicators like activation/adoption and retention by cohort (see Retention, Product activation and Cohort Analysis).

A simple ARPA operating cadence

If you want ARPA to drive decisions (not just appear on a dashboard), use a lightweight monthly routine:

- Start with the trio: MRR, active accounts, ARPA (same time window).

- Segment immediately: at least by plan and acquisition motion.

- Explain the change: expansions, contractions, churn mix, pricing/discounting.

- Check durability: watch churn and contraction in the next 30–90 days for any monetization change.

- Decide one action: packaging, discount policy, onboarding improvements, or ICP refinement.

ARPA won't tell you everything. But it will consistently tell you whether the average account in your business is becoming more valuable—and whether your growth strategy is building a stronger company or just a bigger workload.

Frequently asked questions

ARPA is revenue per account, which fits B2B SaaS where one company can have many users. ARPU is per user and usually needs reliable user counts. ASP is typically the average price of a sold plan or deal. ARPA is best for tracking monetization and mix over time.

There is no universal benchmark because ARPA depends on ICP, pricing model, and sales motion. Self-serve SMB products often land in the tens to low hundreds per month, while mid-market and enterprise can be hundreds to thousands or more. Compare ARPA within your segment and against your own historical trend.

ARPA is a ratio. It can rise if you lose more low-paying accounts than revenue, if you raise prices on remaining customers, or if higher-tier customers become a larger share of your base. Check active account count, churn mix, upgrades, and discounting before concluding you improved monetization.

For subscription businesses, ARPA is usually based on MRR because it normalizes billing intervals and aligns with retention metrics like NRR and GRR. Recognized revenue can be useful for accounting views, but it may be distorted by timing. Pick one definition, document it, and keep it consistent for decisions.

Use MRR normalized from the subscription terms, then include discounts in the MRR value because they change what you actually collect. Exclude one-time charges unless you are explicitly analyzing total revenue per account. Treat refunds and credits consistently so ARPA reflects durable recurring value, not billing noise.