Table of contents

WACC (weighted average cost of capital)

When capital gets more expensive, the same growth plan can go from "smart" to "value-destroying" overnight. WACC is the metric that explains why—and it's one of the cleanest ways to decide whether you should raise, borrow, slow burn, or push harder.

WACC (weighted average cost of capital) is the blended annual "price" you pay for the money funding your company—equity and debt—weighted by how much of each you use. In practice, founders use it as a hurdle rate: projects and strategies should return more than WACC to create value.

What WACC reveals

WACC is less about accounting and more about decision quality under uncertainty. It answers: "What return do our investors and lenders need from this business, given its risk?"

Use cases founders actually run into:

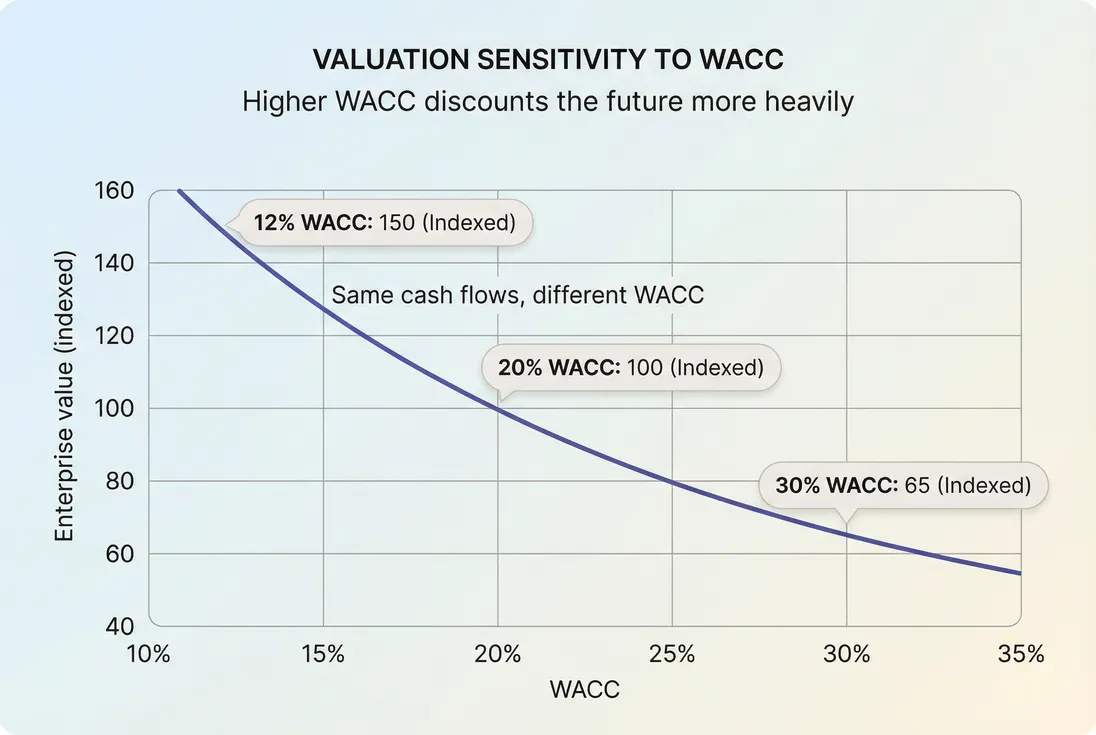

- Valuation sensitivity: Higher WACC lowers what the company is worth for the same future cash flows (especially relevant for Enterprise Value (EV) and EV/Revenue Multiple).

- Growth vs efficiency tradeoffs: If WACC is high, long-payback growth becomes expensive; you need better retention and faster payback.

- Fundraising vs bootstrapping: It's a way to compare dilution cost (Dilution in SaaS) against debt cost and operational risk.

- M&A and buy-vs-build: Discount future synergies and cash flows with a rate that matches risk.

The Founder's perspective: If your plan requires "we'll be profitable later," WACC determines how harshly the market discounts that later. In high-WACC environments, durability (retention + margin) beats "growth at any cost."

How WACC is calculated

At its simplest:

Where:

- E = market value of equity (what equity is "worth" today)

- D = market value of debt

- R e = cost of equity (required return for equity holders)

- R d = cost of debt (interest rate adjusted for fees)

- T = effective tax rate (often near zero for startups with losses and NOLs)

Two founder-relevant simplifications:

- If you have no debt, WACC ≈ cost of equity.

- If you are not paying cash taxes, the tax shield may be minimal, so after-tax debt is closer to pre-tax debt.

A practical estimation workflow

For private SaaS, you typically can't "precisely" measure WACC. You estimate it consistently.

Step 1: Set capital weights (E and D)

Use a market-based view:

- Equity value: last priced round post-money is a starting proxy (imperfect, but better than book value).

- Debt value: outstanding principal (plus any material fees) is usually close enough.

Step 2: Estimate cost of debt (R d)

Use the effective annualized cost:

- Stated interest rate

- Plus amortized upfront fees

- Plus the economic cost of warrants (if any)

Step 3: Estimate cost of equity (R e)

Public-company finance uses CAPM, but early-stage SaaS rarely has a meaningful beta. If you still want the conceptual form:

In founder reality, cost of equity is better approximated as:

- The return your next investors will demand at your current risk (often 20–35% early-stage; lower for later-stage with durable cash flows).

- A hurdle rate aligned to outcomes: if your business is volatile or retention is weak, your equity cost is higher.

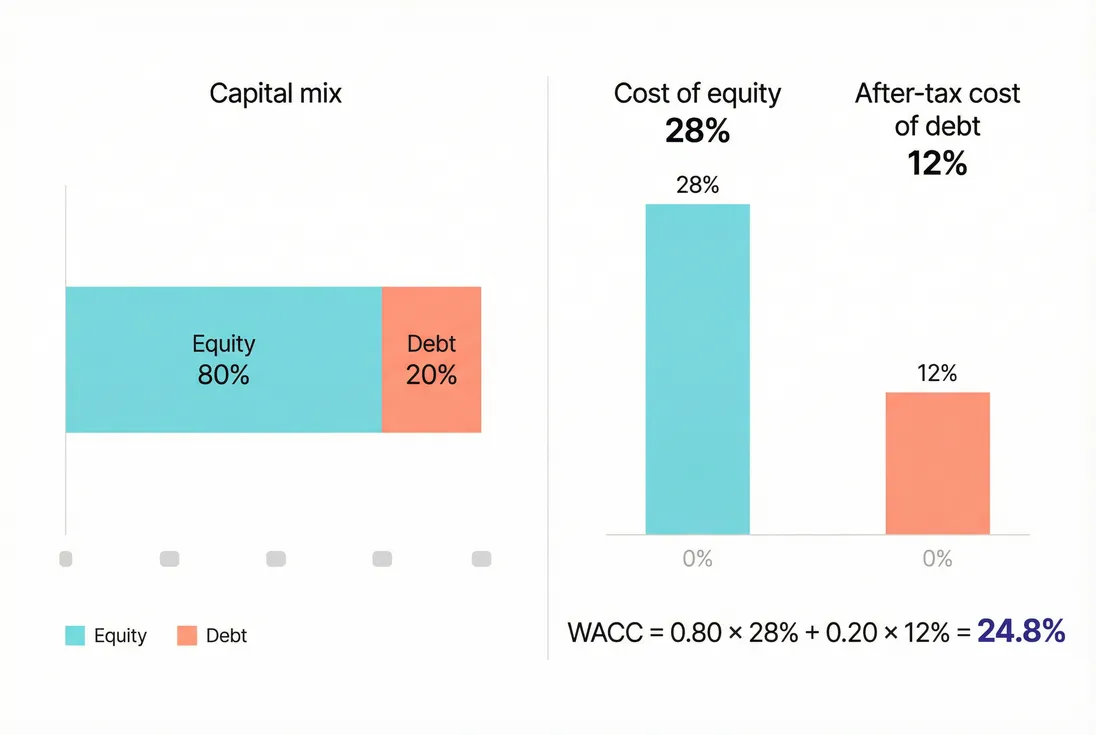

A concrete SaaS example

Assume:

- Equity value (E): $40M

- Venture debt (D): $10M at 12% effective cost

- Effective tax rate (T): 0% (loss-making)

- Cost of equity (R e): 28%

Then:

- Weight of equity = 40 / 50 = 80%

- Weight of debt = 10 / 50 = 20%

- After-tax debt cost = 12% (no tax benefit)

Estimated WACC: ~24.8%

That is a very "startup-normal" number. It implies: if you invest $1 today, you need to believe it returns meaningfully more than ~$1.25 over an appropriate horizon after accounting for risk and execution.

What moves WACC up or down

Founders often assume WACC is mainly about interest rates. Rates matter, but your business quality and financing choices matter just as much.

Drivers of higher WACC (worse)

1) Higher perceived risk (higher cost of equity)

This is the big one for SaaS. Cost of equity rises when:

- Retention weakens (see NRR (Net Revenue Retention) and GRR (Gross Revenue Retention))

- Churn increases (see Customer Churn Rate and Logo Churn)

- Gross margin compresses (see Gross Margin and COGS (Cost of Goods Sold))

- Revenue becomes less predictable (heavy services, one-time payments, high refunds)

2) More expensive debt (higher cost of debt)

This can happen from:

- Rate increases

- Worse terms (fees, warrants, covenants)

- Shorter maturities that increase refinancing risk

3) Capital structure stress (debt increases risk)

Adding debt can increase WACC if it meaningfully increases failure risk, because equity holders demand more return when downside risk rises.

The Founder's perspective: If debt forces you to cut product or sales at the wrong time (because of covenants or cash pressure), it's not "cheap." Cheap capital is the capital that increases your probability of winning.

Drivers of lower WACC (better)

1) Stronger durability signals

- Higher retention and expansion

- Stable cohorts (see Cohort Analysis)

- Improving gross margin

- Longer contract terms and higher committed revenue (see CMRR (Committed Monthly Recurring Revenue))

2) Improved capital efficiency When you need less external capital to reach key milestones, investors price you as lower risk. Operationally, this is connected to:

- Burn Rate and Runway

- Burn Multiple and Capital Efficiency

- Payback discipline (see CAC Payback Period)

3) Better financing options As your metrics strengthen, you can access:

- cheaper debt

- less dilutive equity

- more competitive terms overall

How founders should interpret changes

A change in WACC is rarely "a finance detail." It's the market's way of repricing the bar your plan must clear.

If WACC increases

Implications:

- Valuations fall for the same future cash flows.

- Long payback gets punished. A 24–30 month payback can be unacceptable in practice if capital is expensive and risk is rising.

- You need clearer paths to free cash flow. See Free Cash Flow (FCF) and Operating Margin.

Operational responses that usually make sense:

- Tighten ICP to improve retention before scaling spend.

- Reduce discounting that "rents" ARR (see Discounts in SaaS).

- Shift roadmap toward retention drivers, not just top-of-funnel.

- Revisit hiring plans tied to speculative growth.

If WACC decreases

Implications:

- Future cash flows are worth more today.

- You can rationally accept longer paybacks (within reason) if your retention and gross margin are strong.

- Financing flexibility improves, often enabling faster product or GTM investment.

The risk: teams interpret a lower WACC environment as permission to ignore fundamentals. Don't. Lower WACC increases the value of durable growth; it does not excuse weak retention.

How WACC informs real decisions

WACC becomes useful when you force decisions through it, even approximately.

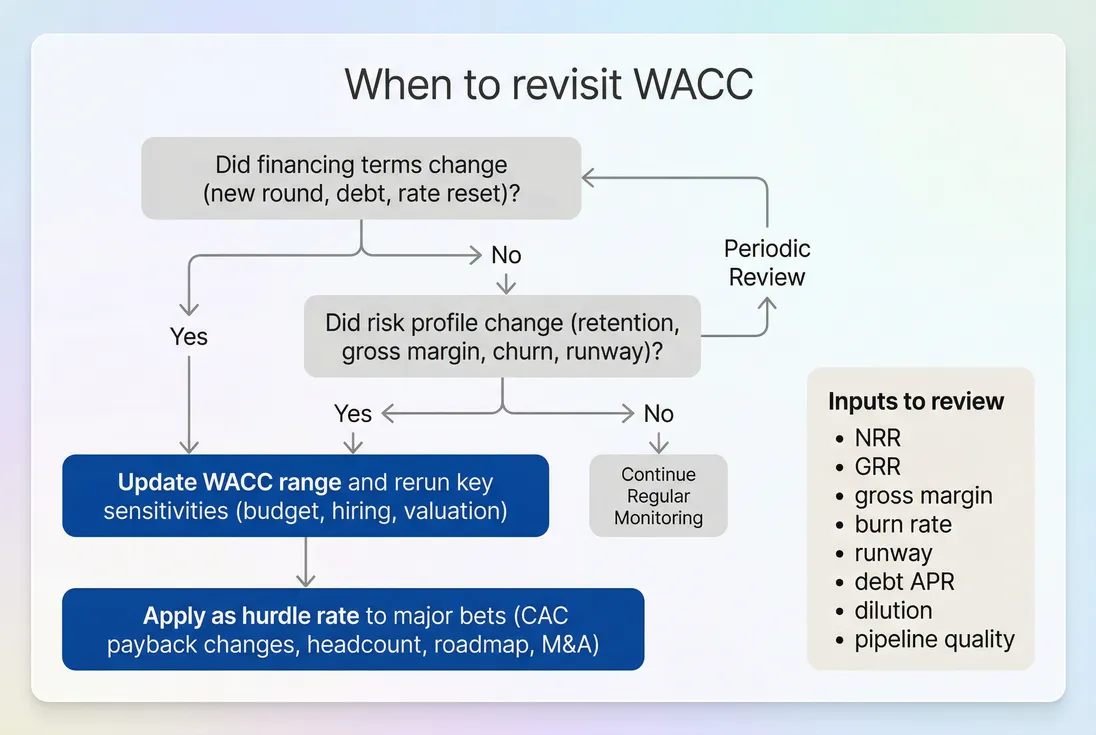

1) Setting a hurdle rate for major bets

For any big initiative—new product line, new region, enterprise pivot—use WACC as the minimum required return and sanity-check the cash flow timing.

A simplified NPV structure (no spreadsheet required for the concept):

If the bet only works when you assume perfect execution and low churn, it's probably below your true WACC.

2) Calibrating CAC payback targets

WACC doesn't replace payback metrics, but it tells you what payback means. A higher WACC implies you should:

- demand faster payback, or

- demand higher confidence retention (better GRR/NRR), or

- require higher gross margin.

Tie this to:

The Founder's perspective: In high-WACC environments, "efficient growth" usually means payback discipline plus retention proof—not just cutting spend.

3) Comparing equity vs debt vs slowing burn

When deciding how to fund the next 18 months, founders often compare:

- Raise equity (dilution is the "cost")

- Take on debt (cash interest + risk)

- Slow burn (opportunity cost)

WACC helps you frame the trade:

- If your WACC is high because risk is high, adding debt can be dangerous even if it looks cheaper.

- If your retention and gross margin are strong and you're close to breakeven, debt can reduce dilution without raising risk too much.

Connect this conversation to:

4) Understanding valuation sensitivity (why WACC hurts)

One reason founders should care: small WACC changes can create big valuation swings, because SaaS value is often "later."

This is also why the same ARR can command very different EV/Revenue Multiple depending on durability signals like retention, margin, and churn.

Common mistakes (and how to avoid them)

Mistake 1: Treating WACC as a precise number

For private SaaS, WACC is a decision tool, not a measurement instrument. Don't debate 21% vs 23%. Do:

- pick a reasonable range (example: 22–28%)

- run sensitivity around it

- update when risk or capital terms change

Mistake 2: Using book values for weights

WACC weights are about economic reality, not accounting. If you raised at a $60M post-money, your equity weight isn't the common stock par value on a balance sheet.

Mistake 3: Assuming a tax shield you don't have

Many startups aren't paying taxes, so the "(1 − T)" benefit may not show up for years (or ever, if you don't generate taxable income). Use an effective tax rate that matches reality.

Mistake 4: Ignoring customer durability in the cost of equity

If your Net MRR Churn Rate is worsening or your cohorts are decaying faster, your equity cost is higher even if top-line growth looks strong. Investors price risk-adjusted durability, not just bookings.

Mistake 5: Not matching discount rate to risk

If you're evaluating a risky new product line or a new segment, discounting at corporate WACC can be too generous. For big strategic bets, add a risk premium or use a higher hurdle rate.

A founder-friendly way to use WACC (without overbuilding)

If you want WACC to improve decision-making (not become a finance rabbit hole), do this:

- Pick a base hurdle rate you can defend (often 20–30% for early-stage; lower as cash flows become durable).

- Use ranges, not points (example: 22%, 26%, 30%).

- Tie updates to operating triggers:

- Force big bets to clear the bar:

- If you're extending payback, show why retention and gross margin make it rational.

- If you're taking debt, show why it doesn't raise failure risk.

The Founder's perspective: WACC is the "price of tomorrow." If you're buying growth today (through burn, discounts, or debt), WACC tells you how expensive that purchase really is—and whether you can afford it.

Quick benchmark guidance (what "good" looks like)

There is no universal "good WACC" for SaaS. But you can use these directional heuristics:

| Company profile | Typical WACC direction | What usually drives it |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-product-market fit | Highest | Extreme uncertainty, weak predictability |

| Early PMF, improving retention | High but falling | Better cohort stability, clearer GTM |

| Scaled growth with strong NRR and margin | Medium | Durability reduces equity risk premium |

| Profitable, predictable cash flows | Lowest | Debt becomes cheaper and usable, equity risk premium declines |

If you want WACC to trend down over time, focus less on "finance engineering" and more on the fundamentals that reduce perceived risk: retention, gross margin, and capital efficiency.

Related GrowPanel Academy links

- Burn Multiple

- Capital Efficiency

- Free Cash Flow (FCF)

- Enterprise Value (EV)

- EV/Revenue Multiple

- NRR (Net Revenue Retention)

- GRR (Gross Revenue Retention)

- CAC Payback Period

Frequently asked questions

Treat WACC as your hurdle rate for long payback decisions: hiring, product bets, M&A, and financing. If an initiative cannot plausibly return more than WACC (after realistic risk and delays), it destroys value even if it grows ARR. Use it to set payback and margin targets.

Early-stage SaaS usually has no meaningful debt, so WACC is basically the cost of equity. Practically, that often lands in the 20 to 35 percent range depending on stage, retention, and market risk. The exact number matters less than consistency and using a conservative hurdle rate.

Not always. Debt is usually cheaper than equity, but taking debt can increase risk (default risk, covenant pressure, reduced flexibility). That can raise the cost of equity and sometimes offset the benefit. The key is whether debt improves runway and outcomes without meaningfully increasing failure probability.

WACC can rise when rates increase, investors reprice risk, your churn worsens, or your cash flows look less durable. ARR growth helps, but durability matters more: gross margin, retention, and predictability. If growth is bought with heavy burn or discounting, perceived risk can increase.

Use both. CAC payback is a near-term liquidity lens; WACC is a long-term value lens. A payback that looks acceptable can still destroy value if it requires high ongoing retention assumptions that are not true. Pair payback targets with retention and margin reality checks.