Table of contents

Uptime and SLA

Uptime is one of the fastest ways to lose (or earn) trust at scale. A single avoidable outage can stall an enterprise deal, trigger procurement scrutiny, and quietly increase churn risk for months—especially for high-ARPA customers.

Definition (plain English): Uptime is the percentage of time your product is available and functioning as defined by your measurement rules. An SLA (service level agreement) is the contractual promise you make to customers about availability (and sometimes support response), including what happens—usually credits—if you miss.

What this metric reveals

Founders tend to think about uptime as an engineering quality metric. Customers experience it as a business continuity metric. The difference matters.

- Uptime (measured reality): What your monitoring says happened.

- SLO (service level objective): Your internal reliability target (often stricter than your SLA).

- SLA (contract): The commitment customers can enforce.

The business questions uptime answers are practical:

- Will reliability block revenue growth? (Enterprise deals, expansions, renewals.)

- Is churn risk rising for a specific segment? Outages don't hit all customers equally.

- Are we accumulating reliability debt? Repeated small incidents often predict a major one.

- Are we investing in the right fixes? Uptime by itself doesn't tell you what to fix; patterns do.

The Founder's perspective: Uptime is a revenue-protection lever. If your largest accounts can't trust availability, you'll feel it in slower expansions, higher Logo Churn, and pressure on pricing and discounts during renewals.

How to calculate uptime correctly

Most uptime arguments aren't about math—they're about definitions: what counts as downtime, what measurement window applies, and whose experience you measure.

The core calculation

A defensible basic formula is:

That looks simple until you define "downtime minutes."

Common approaches (choose intentionally):

- Endpoint availability: Your health check endpoint returns success.

- User-centric availability: Real users can complete key actions (login, create record, run job).

- Composite availability: Weighted score across core services (API, web app, background jobs).

User-centric definitions are usually closer to customer reality, but harder to measure well.

Translate "nines" into minutes

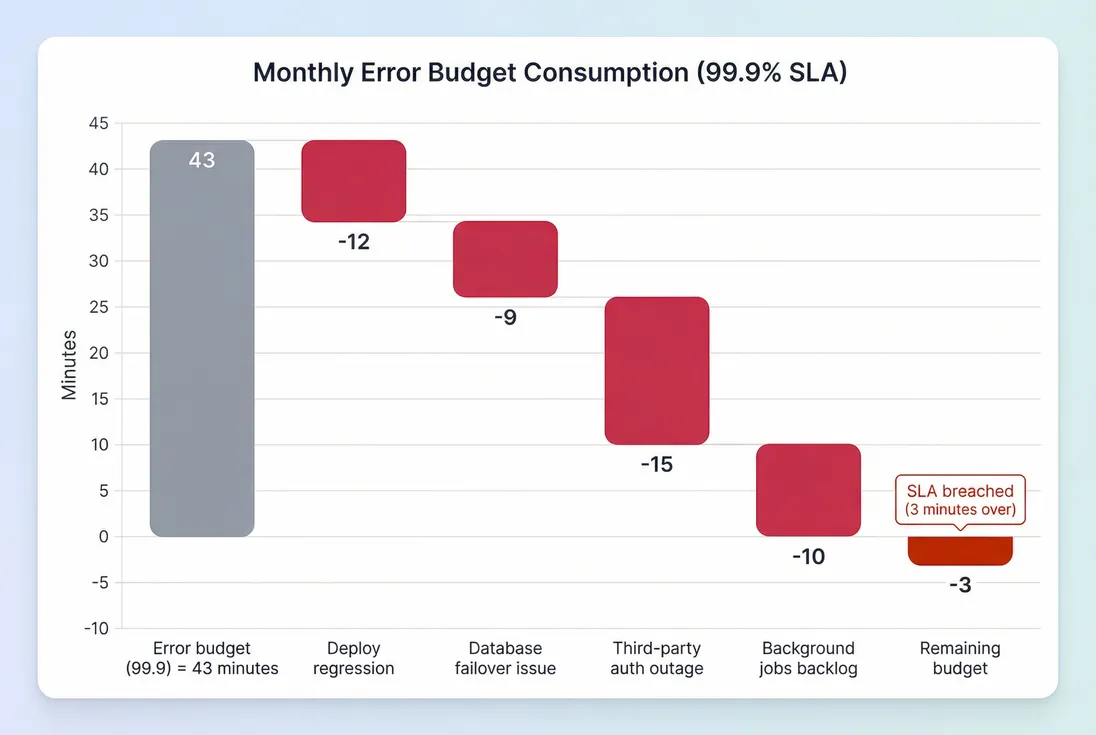

The fastest way to make uptime actionable is to convert it into an error budget (allowed downtime).

Here's what that means in practice:

| Target uptime | Allowed downtime per month (30 days) | Allowed downtime per year |

|---|---|---|

| 99.5% | ~216 minutes (3.6 hours) | ~43.8 hours |

| 99.9% | ~43 minutes | ~8.8 hours |

| 99.95% | ~22 minutes | ~4.4 hours |

| 99.99% | ~4 minutes | ~52 minutes |

The jump from 99.9% to 99.99% is not "one more nine." It's roughly 10x less downtime. That typically requires real architectural and operational changes (redundancy, mature incident response, more testing rigor), not just "try harder."

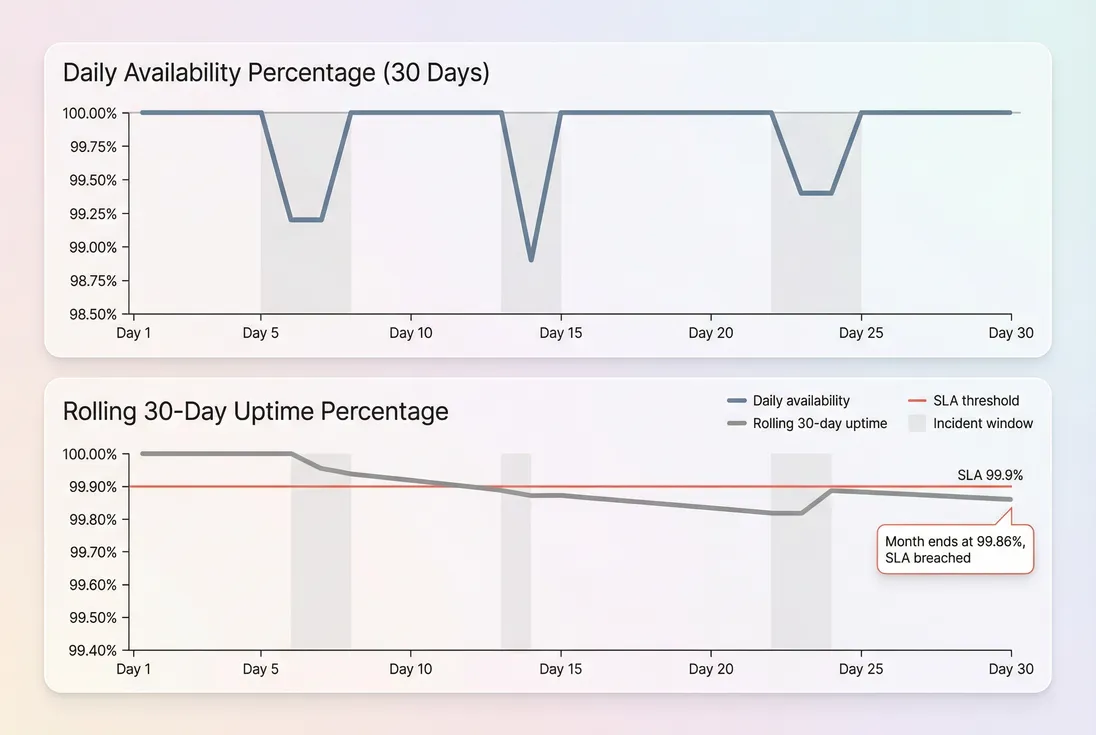

Rolling uptime vs calendar uptime

SLA language often specifies a calendar month. Operationally, you should track:

- Monthly uptime (contract compliance)

- Rolling 30-day uptime (early warning before the month closes)

This prevents "we'll make it up later" thinking when you've already burned most of the month's error budget.

What counts as downtime (the rules matter)

Your SLA and reporting should explicitly define:

- Partial outages: If 30% of users can't log in, is that downtime?

- Degraded performance: Is "up but unusably slow" counted?

- Regional impact: If only EU is down, do you count it?

- Planned maintenance: Is it excluded, and what notice is required?

- Third-party failures: If your cloud provider fails, do customers still see it as "your" downtime? (Yes.)

A practical founder rule: measure in a way you'd accept if you were the customer. If you try to "definition-lawyer" uptime, you may win the metric and lose renewals.

What breaks uptime in practice

Uptime is an outcome. To improve it, you need to understand the typical drivers and how they show up in your data.

The big four outage patterns

Change-driven incidents (deploys, config changes, migrations)

Often clustered around release windows. These are highly fixable with better rollout controls.Capacity and scaling failures (traffic spikes, noisy neighbors, exhausted queues)

These show up as "slowdown first, outage later." Performance SLOs matter here.Dependency failures (databases, third-party APIs, auth providers)

The hidden killer: your app can be "up" but core workflows are broken.Data and job pipeline issues (background jobs stuck, delayed processing)

Customers call this downtime even if your homepage loads.

The Founder's perspective: If uptime is slipping, don't start by demanding more heroics. Start by asking: are incidents mostly caused by changes, scale, dependencies, or data pipelines? Each category implies a different investment—tests and rollouts, capacity planning, resilience, or operational tooling.

The most useful companion metrics (lightweight)

Even if you don't go deep on SRE frameworks, you should track:

- Incident count per week/month

- Mean time to detect (how long until you know)

- Mean time to recover (how long until customers are back)

- % incidents tied to releases

- Repeats of the same root cause (a technical debt signal)

This is where reliability intersects with Technical Debt: recurring root causes are debt principal and interest showing up as downtime.

How to set and negotiate SLAs

If you sell to larger customers, an SLA becomes a sales and trust artifact—not just an ops document. The goal is a commitment you can meet consistently, with remedies you can honor without blowing up margins.

Start with internal SLOs, then publish SLA

A common, effective structure:

- Internal SLO: 99.95% (what you aim to achieve)

- External SLA: 99.9% (what you contractually promise)

That buffer protects you from edge cases and measurement disputes while still being meaningful to customers.

Use a tiered approach

Not every customer needs the same commitment. Consider tiers tied to plan level or contract size:

- Standard: 99.9% monthly uptime

- Premium: 99.95% monthly uptime (plus faster support response times)

- Custom: only if you can truly deliver (often requires architecture or staffing changes)

This ties directly to unit economics: higher commitments increase costs (on-call, redundancy, multi-region, better observability), which should be reflected in pricing and margin expectations. Use COGS (Cost of Goods Sold) and Gross Margin thinking, not just engineering ambition.

Define credits that are meaningful—but capped

SLA remedies are usually service credits, often a percentage of monthly fees. A simple credit structure might look like:

- 99.9% to 99.0%: 10% credit

- 99.0% to 98.0%: 25% credit

- Below 98.0%: 50% credit

- Monthly cap: 50%

A generic credit formula:

Operationally, credits are also a retention tool: issue them quickly, don't force customers to fight, and pair them with a clear remediation plan. If credits start becoming frequent, treat them as a leading indicator of future churn and revenue leakage (similar in spirit to how you'd treat Refunds in SaaS).

Don't hide behind exclusions

You will need exclusions (scheduled maintenance, force majeure, customer-caused issues). Keep them tight:

- Scheduled maintenance excluded only with clear advance notice and maximum window size.

- Customer misconfiguration excluded only if you provide clear documentation and guardrails.

- Third-party dependencies: be cautious. Customers don't care whose fault it is.

If procurement pushes for strict terms, negotiate with math: show what each extra nine implies in downtime minutes, and what it would require in cost and architecture.

How founders use uptime data

Uptime becomes powerful when it connects to decision-making across product, success, and finance.

1) Prioritize reliability work with error budget

Treat your allowed downtime as a budget you spend. Once you burn it, you switch behavior: slow releases, focus on stability, fix repeat causes.

This helps you avoid a common trap: treating every incident as equally important. A 12-minute deploy regression you can eliminate permanently is often more valuable than shaving 30 seconds off an on-call process.

2) Connect incidents to churn and expansion risk

Outages don't affect revenue evenly. A 20-minute incident during peak hours for your top 10 accounts can be more damaging than an hour at 2 a.m. for a handful of free users.

Practically:

- Tag accounts affected by major incidents.

- Track their behavior and relationship health for the next 30–90 days.

- Watch retention outcomes: Customer Churn Rate, Logo Churn, and revenue retention like NRR (Net Revenue Retention) and GRR (Gross Revenue Retention).

- Feed reliability issues into Churn Reason Analysis so "stability" becomes a measurable churn driver, not a vague complaint.

This is also where a Customer Health Score should include reliability exposure (even a simple flag: "impacted by P1 incident in last 30 days").

The Founder's perspective: If you want clean retention metrics, you have to treat reliability incidents like a pipeline of churn risk. The incident ends in an hour; the renewal risk can last all quarter.

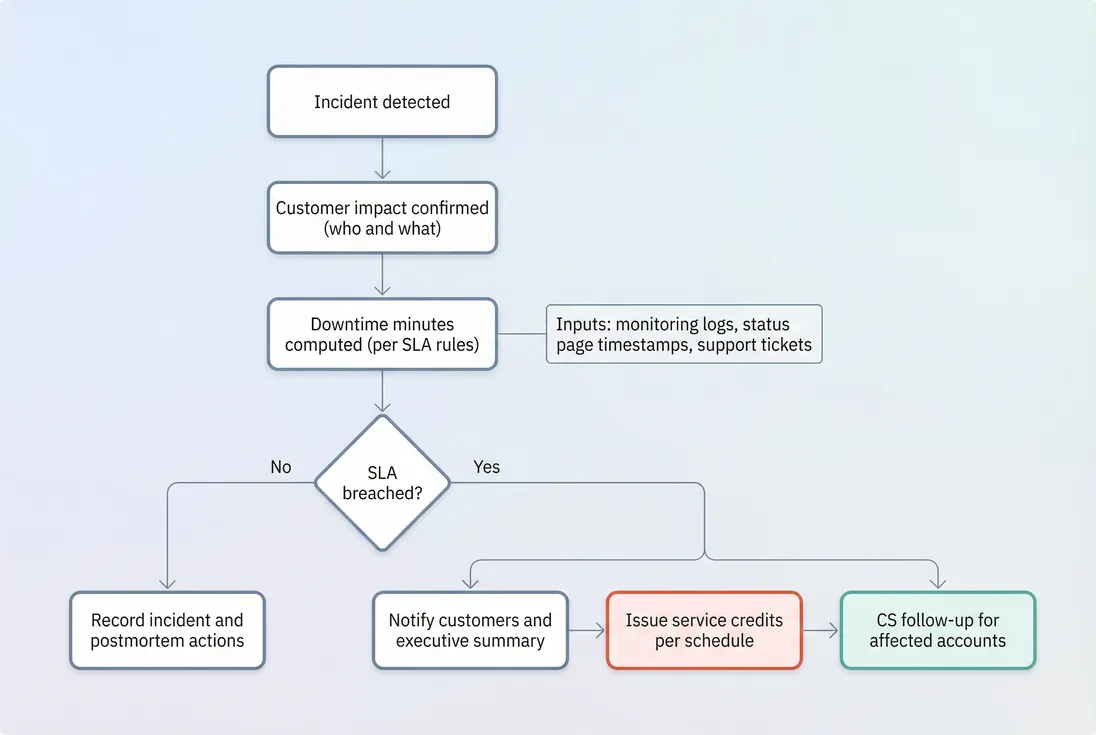

3) Make SLA response a customer-success motion

SLA compliance is not just an engineering report—it's a workflow:

- Detect and resolve incident

- Confirm impact window and affected services

- Decide whether SLA breach occurred (per contract rules)

- Proactively communicate: what happened, what changed, what to expect

- Issue credits (fast)

- Run postmortem and track follow-through

4) Decide when reliability investment is worth it

Reliability work competes with growth work. The right decision depends on where uptime sits relative to your go-to-market motion:

- If you're product-led and self-serve, moderate uptime issues may hurt activation and conversion (watch Conversion Rate).

- If you're selling mid-market/enterprise, uptime is often a gating factor in procurement and renewal. A weak SLA can slow Sales Cycle Length and force discounting.

- If your customers run mission-critical workflows, reliability directly protects ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue) concentration.

Tie this back to capital efficiency: if uptime problems create churn, you'll pay for it twice—lost revenue and wasted CAC. That shows up in metrics like CAC Payback Period and Burn Multiple.

Benchmarks and practical targets

Benchmarks only help if you match them to customer expectations and product criticality.

| Context | Typical external SLA | Practical note |

|---|---|---|

| Early-stage SMB SaaS, non-critical | No SLA or 99.5–99.9% | Publish status page and measure internally; don't overpromise. |

| B2B SaaS for internal workflows | 99.9% | Most common "default" once you're serious about teams. |

| Mid-market with operational dependency | 99.9–99.95% | Often requires better incident response and resilience. |

| Enterprise, compliance-heavy, mission-critical | 99.95–99.99% | Expect strict definitions, reporting, and escalation processes. |

A useful founder heuristic: don't sell 99.99% unless you can explain exactly how you achieve it (redundancy, failover testing, on-call maturity). Customers will ask, and you should have credible answers.

Common measurement pitfalls

A few mistakes cause most uptime confusion:

- Only measuring "server up." Customers care about workflows, not pings.

- Ignoring degraded performance. "Up but unusable" is downtime in disguise.

- Excluding too much. If your metric looks good but customers are angry, your definition is wrong.

- Not aligning timestamps across teams. Support, status page, and monitoring must reconcile.

- No segmentation. Uptime for a minor feature should not dilute uptime for core workflows.

If you're seeing rising churn and also reliability complaints, don't guess—connect the dots with retention analysis. Even a simple segmentation ("accounts impacted by P1 vs not impacted") can reveal whether reliability is a true churn driver.

If you want to take uptime from "a percentage on a dashboard" to a founder tool, do three things: define downtime in customer terms, translate targets into minutes, and run an operating cadence that treats error budget like money. That's how uptime stops being abstract—and starts protecting renewals and growth.

Frequently asked questions

Early-stage SaaS can often operate at 99.5 to 99.9 percent while the product and infrastructure stabilize, as long as you communicate clearly and fix repeat issues. Once you sell into larger teams or mission-critical workflows, 99.9 percent becomes table stakes. Enterprise and regulated buyers often expect 99.95 percent or higher.

The nines hide the reality. 99.9 percent uptime allows about 43 minutes of downtime per month, while 99.99 percent allows about 4 minutes. That difference should drive engineering and process investment decisions. Always translate targets into minutes per month and decide whether your team can realistically stay within that budget.

If you are primarily SMB self-serve and your product is not mission-critical, you can delay a contractual SLA and instead publish a status page and internal SLOs. If enterprise deals are in the pipeline, an SLA is often part of procurement. Offer a conservative SLA you can honor and keep stronger reliability goals internal.

Most SLAs exclude scheduled maintenance that is announced in advance, and they often exclude issues caused by customer misconfiguration, force majeure, and sometimes upstream provider failures. Be careful: excluding too much can erode trust and slow sales cycles. A practical approach is limited exclusions, clear notification rules, and a credit schedule with a monthly cap.

Treat a breach as both a customer-success event and a reliability learning loop. Issue credits quickly per the contract, proactively explain impact, and share the remediation plan. Then run a postmortem that produces concrete changes: monitoring gaps closed, runbooks updated, and repeat-cause fixes scheduled. Track whether affected accounts show increased churn risk.