Table of contents

Time to Value (TTV)

Founders feel Time to Value (TTV) most when growth "should" be working but isn't: pipeline converts, revenue lands, and then customers stall, complain, and churn before renewal. TTV turns that fuzzy problem into a measurable clock—and gives you a lever to improve retention, expansion, and payback without needing more leads.

Time to Value (TTV) is the time between a customer's start point (signup, purchase, or kickoff) and the moment they achieve their first meaningful outcome in your product.

The hard part isn't the subtraction. It's defining "start" and "value" in a way that reflects real customer success and leads to better decisions.

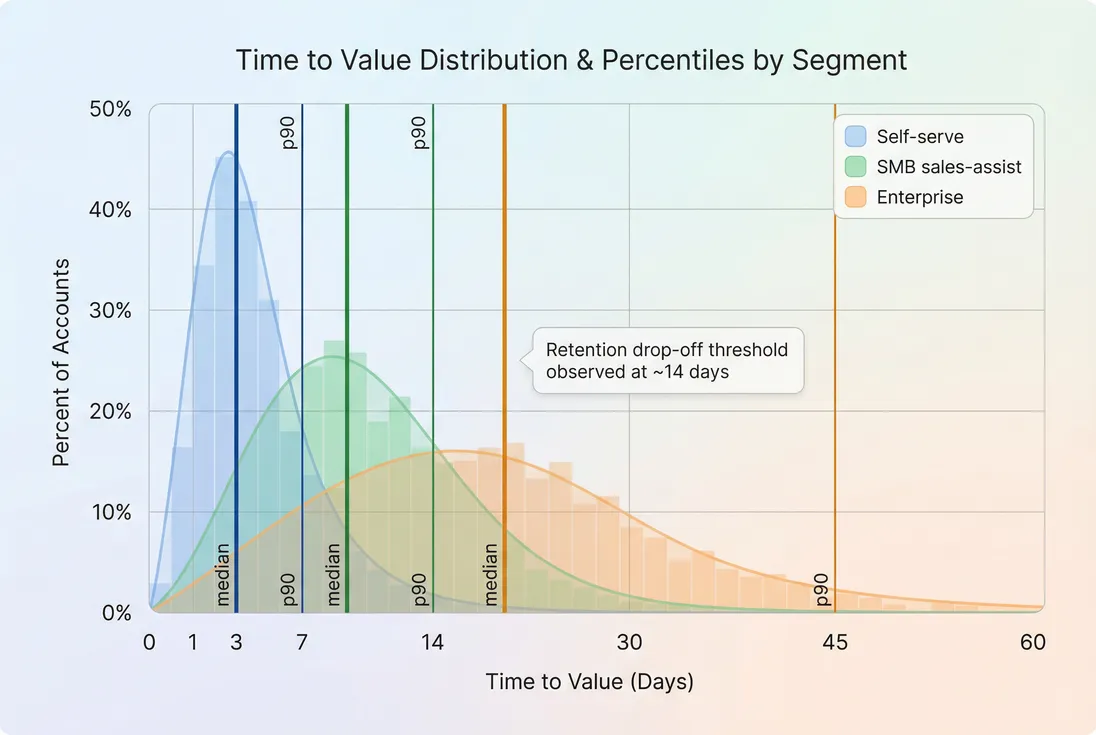

TTV is rarely one number—median and p90 by segment show whether your problem is the typical user experience or the long tail of complex accounts.

What counts as value

If you define value poorly, you'll optimize onboarding for the wrong thing—fast clicks instead of durable outcomes. A strong "value event" has three properties:

- Customer-recognized outcome: the customer would agree they made progress.

- Observable in data: you can detect it reliably (event, status change, usage threshold).

- Predictive: customers who reach it retain at meaningfully higher rates.

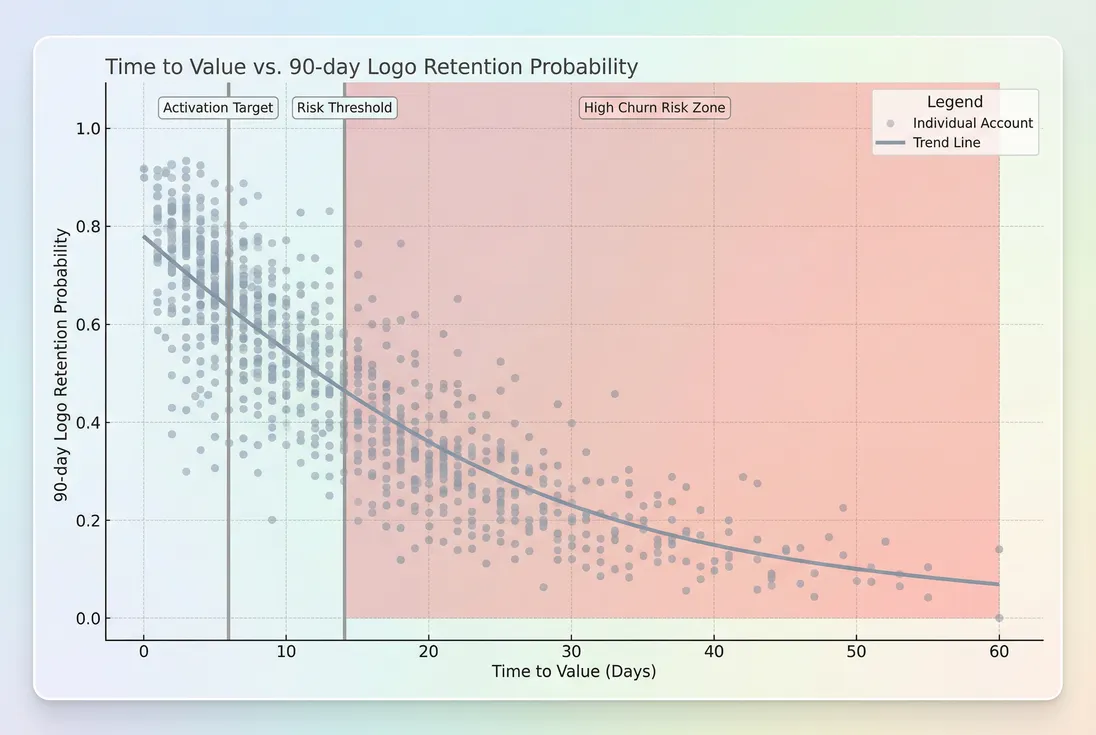

This is where TTV connects directly to retention analysis. If your "value event" doesn't separate retention cohorts, it's not value—it's activity. Use Cohort Analysis to validate that reaching the event early leads to better retention.

Common value event patterns

Pick the simplest event that represents "the product worked" for the customer:

- Collaboration products: first workspace with at least 2 invited teammates and 1 shared artifact.

- Analytics products: first dashboard created and first data source successfully connected.

- Dev tools: first successful deploy, pipeline run, or alert fired.

- Sales/CS tools: first pipeline imported and first report delivered to a stakeholder.

- Finance tools: first invoice sent, reconciliation complete, or payout processed.

For many products, you'll need a composite value event (two or three conditions) to avoid gaming. Example: "created dashboard" alone can be a hollow action. "Connected data source + dashboard viewed twice by two users" is closer to value.

The Founder's perspective

If your team debates whether a value event is "too hard," that's usually a sign it's closer to the truth. A value event should be hard enough that it indicates real adoption—otherwise you'll celebrate fast TTV while churn stays high.

Time to first value vs time to full value

Founders often mash these together and lose signal.

- Time to first value (TTFV): earliest meaningful outcome. Best for onboarding and activation work.

- Time to full value (TTFV plus depth): when the customer is using the product in the sustained way that matches your promised ROI.

In practice:

- Manage first value weekly.

- Review full value monthly/quarterly because it depends on behavior change, integrations, and rollout.

How to calculate TTV

You want a definition that is consistent, segmentable, and resistant to edge cases (paused onboarding, delayed kickoff, implementation projects).

Choose your start timestamp

Your "start" depends on your go-to-market motion:

- Self-serve / PLG: signup time, trial start, or first session.

- Sales-led: contract start date, kickoff meeting date, or provisioning date.

- Implementation-heavy: kickoff date is often more honest than contract signature, because real work begins there.

The key is consistency. If sales closes deals that sit unimplemented for 30 days, using contract signature will make TTV look worse—but it will also accurately surface a real revenue risk.

To avoid confusion, many teams track two clocks:

- Commercial TTV: from contract start → value

- Product TTV: from first login → value

Use median, not average

TTV almost always has a long tail (some accounts take a long time). Averages get distorted by a few stuck implementations.

Track:

- Median TTV (typical experience)

- p75 or p90 TTV (long-tail friction)

- % reaching value within target window (operational SLA)

If you need a single KPI for weekly operations, use median plus a p90 guardrail.

A practical aggregation approach

For a time period (say, customers who started in a month), compute TTV per account, then summarize.

If you sell to both SMB and enterprise, also consider an ARR-weighted view so your biggest accounts don't get drowned out by self-serve volume.

Use this carefully: it can hide that most customers are struggling (if a few large accounts onboard quickly with high-touch support).

Segment first, then optimize

A single blended TTV is usually misleading. Segment by what actually changes onboarding difficulty:

- Plan / package

- Company size

- Use case

- Data integration required vs not required

- Sales-led vs self-serve

- Region/time zone (for scheduling and support coverage)

Once you do this, you'll usually find you don't have one TTV problem—you have one segment with an acute problem.

What drives TTV

TTV is shaped by product design, customer readiness, and your delivery model. When founders miss targets, it's often because they treat TTV as "an onboarding problem" rather than a cross-functional system.

Product friction

Typical drivers:

- Too many required steps before anything works

- Unclear setup instructions

- Permissions and admin bottlenecks

- Missing templates or default configuration

- Slow feedback loops (e.g., "wait 24 hours for data")

Operationally, your job is to reduce the critical path: the minimum set of steps needed to reach value.

Time-to-data and integration overhead

Any product that needs data to be useful will fight TTV. Two common failure modes:

- Integration is required, but hard → TTV blows out, p90 gets ugly.

- Integration is optional, but value depends on it → customers "use" the product without ever reaching real value.

A strong pattern is to provide a "starter value" path that works without full integration, then pull users into deeper setup after first value.

Onboarding capacity and responsiveness

Even with a great product, TTV can worsen when:

- Support response times slip

- Customer success is understaffed

- Handoffs between sales → CS → implementation are unclear

That's why TTV is also a resourcing and process metric.

Customer effort and behavior change

If the customer must change a workflow (train the team, update process, migrate data), TTV depends on their internal execution. Pair TTV with CES (Customer Effort Score) and onboarding completion to understand whether customers are blocked or simply not prioritizing adoption.

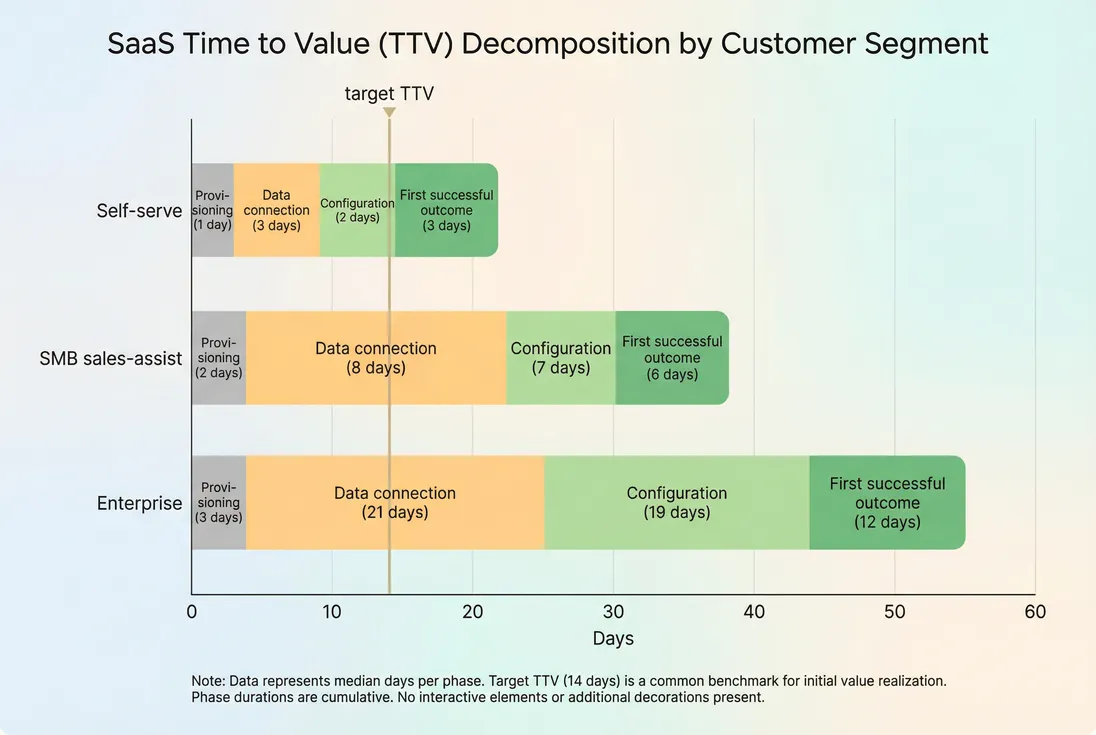

Decomposing TTV by phase tells you where to invest: product simplification, integration work, or onboarding process capacity.

What changes in TTV mean

TTV is a leading indicator. When it moves, it's usually telling you something before Churn Rate or Logo Churn fully reflects it.

When TTV improves

If median and p90 both drop, you likely improved the system:

- onboarding flow is clearer

- setup steps are fewer

- time-to-data is faster

- better templates or defaults

- better CS coverage or automation

Watch for the second-order effect: improved TTV should lift early retention and reduce support load. Validate with retention cohorts and early renewals.

When TTV worsens

Treat it like an outage—investigate immediately. Common culprits:

- You moved upmarket: larger accounts require security reviews, SSO, more stakeholders.

- You added complexity: new required fields, new setup steps, pricing/packaging changes that require more configuration.

- Implementation backlog: kickoff delays, slow integration help, long support queues.

- Lead quality slipped: wrong ICP, customers who can't activate.

This is where segmentation pays off. A flat median with a worsening p90 is a classic sign of "enterprise friction" or "integration complexity," not a universal product issue.

The Founder's perspective

A worsening p90 TTV is often a hidden churn pipeline. Those customers haven't churned yet because they're still "trying." If you don't shorten their path to value now, you'll see it later as churn, contraction, and ugly retention cohorts.

How TTV connects to CAC payback

TTV doesn't just affect churn; it affects how quickly revenue becomes "real" in the customer's mind. Longer TTV typically means:

- slower expansion and seat rollout

- higher risk of refunds or non-renewal

- more CS cost per dollar of ARR

That's why TTV often shows up indirectly in CAC Payback Period. If you sell annual contracts, you might get cash upfront, but payback in economic terms still depends on retention and durable adoption.

How TTV can mislead you

A few traps:

- Gaming the value event: customers hit it quickly, but it doesn't correlate with retention.

- Ignoring "no value" customers: you only measure TTV for accounts that eventually reach value. You also need the % that never reach value (or take longer than your window).

- Blending motions: self-serve and enterprise in one number creates noise and wrong priorities.

- Changing the definition midstream: treat definition changes like a metric migration—document it and annotate trend breaks.

A practical fix: report TTV alongside "activation rate" (share of customers who reached value within X days). Pair that with Onboarding Completion Rate to distinguish between customers who are stuck vs customers who are inactive.

How founders use TTV

TTV becomes powerful when it directly drives decisions in product, onboarding, and go-to-market.

Set an explicit TTV target

Targets should reflect your motion and customer attention span. A simple starting point:

| Motion / product type | Typical first-value target | What usually dominates |

|---|---|---|

| Self-serve PLG | minutes to 1 day | product clarity, templates |

| SMB sales-assist | 1–14 days | onboarding guidance, time-to-data |

| Mid-market | 2–6 weeks | integration, training, rollout |

| Enterprise / regulated | 1–4 months | security, procurement, implementation |

Use this table as a first guess, then refine it by finding the TTV threshold where retention drops sharply (often visible in cohorts).

Decide what to fix first

Use your TTV decomposition (by phase) to pick the highest-leverage work:

- If provisioning dominates: automate provisioning, reduce manual steps, improve internal handoffs.

- If data connection dominates: invest in connectors, better docs, better error messages, faster time-to-first-sync.

- If configuration dominates: ship templates, guided setup, defaults, importers.

- If first outcome dominates: improve in-app guidance, sample data, and "next best action."

This avoids the common founder mistake: "Let's redesign onboarding." Instead, you fix the specific bottleneck.

Tie TTV to retention cohorts

TTV is central to trial performance—see How many days should a SaaS trial be? and Designing the perfect SaaS trial for how to align trial length with TTV. GrowPanel's trial insights can help you visualize TTV alongside trial conversion and activation.

TTV is only worth managing if it predicts retention. Do a simple cut:

- customers with TTV ≤ target window

- customers with TTV > target window

- customers who never reached value

Then compare retention. If the gap is small, your value event is wrong—or your product's retention drivers happen later than you think. Use Retention and cohort views to validate.

If longer TTV correlates with worse retention, shortening TTV is not just onboarding polish—it's a revenue protection project.

Use TTV to improve packaging

TTV is often a packaging problem disguised as onboarding:

- If the entry plan requires integrations or admin permissions, many accounts can't reach value quickly.

- If the first value path requires premium features, trials will feel broken.

Founders can use TTV to redesign the "first success" path so customers can reach value before they hit paywalls or complexity. This connects naturally to Free Trial decisions and your Freemium Model boundary.

Use TTV to allocate customer success

If you run a mixed motion, TTV can help you decide which accounts deserve high-touch onboarding:

- High ARR potential + high predicted TTV risk → allocate onboarding support early.

- Low ARR + low predicted TTV risk → keep it self-serve.

This is one of the cleanest ways to reduce onboarding cost while improving outcomes.

Operational cadence that works

A founder-friendly cadence looks like this:

- Weekly: median TTV, p90 TTV, activation-within-target %, by key segment.

- Biweekly: top 3 bottlenecks by phase (from TTV decomposition).

- Monthly: correlate TTV bands to retention and expansion outcomes (cohorts).

- Quarterly: review whether your value event definition still matches the product promise.

If you already track revenue and churn in a tool like GrowPanel, pair TTV analysis with revenue-side metrics like MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue), NRR (Net Revenue Retention), and cohort retention to see whether faster value is translating into better business outcomes.

When TTV becomes the constraint

TTV is your constraint when you see these patterns together:

- strong acquisition but weak activation

- good initial conversion but weak retention

- high support load early in lifecycle

- customers asking for help with basic setup repeatedly

If your growth feels capped, reducing TTV is one of the few improvements that can increase conversion, retention, and expansion simultaneously—because it makes your product deliver on its promise faster.

The goal isn't to make onboarding "fast." It's to make value inevitable—and then measure how long it takes so you can keep removing friction until the metric stabilizes at a level your customers (and your economics) can sustain.

Frequently asked questions

A good TTV is whatever gets customers to a meaningful outcome before motivation drops and internal stakeholders lose interest. Self-serve products often target minutes to hours, SMB tools target days, and enterprise platforms can be weeks. Use your own retention and churn breakpoints to set targets.

Measure both, but don't mix them. Time to first value is your onboarding and activation speed; it predicts early churn and trial conversion. Time to full value reflects deep adoption and expansion potential. For most founders, first value is the operational KPI and full value is strategic.

Choose an outcome that a customer would recognize as progress even if they never upgraded again. It should be observable in product data and correlate with retention. Avoid vanity events like account creation or logging in. Validate by comparing retention between customers who hit the event and those who do not.

Use median to track the typical experience and p90 to expose friction for slower accounts like enterprise, low-tech, or complex integrations. A stable median with a worsening p90 usually means your long-tail customers are struggling. That often requires onboarding changes, not just product tweaks.

Longer TTV delays expansion, increases support load, and raises the odds customers churn before forming habit. That reduces gross retention and pushes out CAC payback because revenue ramps slower. Pair TTV trends with retention cohorts and churn reason analysis to confirm if onboarding speed is the limiting factor.