Table of contents

TAM (total addressable market)

Founders rarely fail because the market is "too small." They fail because they build and hire against a market story that isn't real, then discover too late that acquisition costs, sales cycles, or buyer budgets don't support the plan.

TAM (total addressable market) is the maximum annual revenue your company could generate if you captured 100% of the customers who could reasonably use your product, at the prices you assume, within a defined market category.

TAM is not your forecast. It's a boundary line that forces clarity about: who the buyer is, what you charge, and what "counts" as your market.

What TAM reveals (and what it doesn't)

TAM is useful because it answers a handful of high-stakes questions quickly:

- Is this market large enough to justify the product and go-to-market motion?

- Are we building a niche business (great) or accidentally trapped in one (not great)?

- Do our pricing and packaging choices leave money on the table?

- Are we defining the market in a way that matches how buyers actually purchase?

What TAM doesn't tell you:

- How fast you can grow (that depends on distribution and execution)

- Whether you will win (competition and differentiation matter)

- Whether you can access the market (that's closer to SAM (Serviceable Addressable Market) and SOM (Serviceable Obtainable Market))

The Founder's perspective

Use TAM to prevent category mistakes: building an enterprise sales team for a market that only supports SMB pricing, or pricing like SMB when the buyer is a regulated enterprise with real budget.

How to calculate TAM without fooling yourself

There are three common approaches. In SaaS, the most defensible is usually bottom-up.

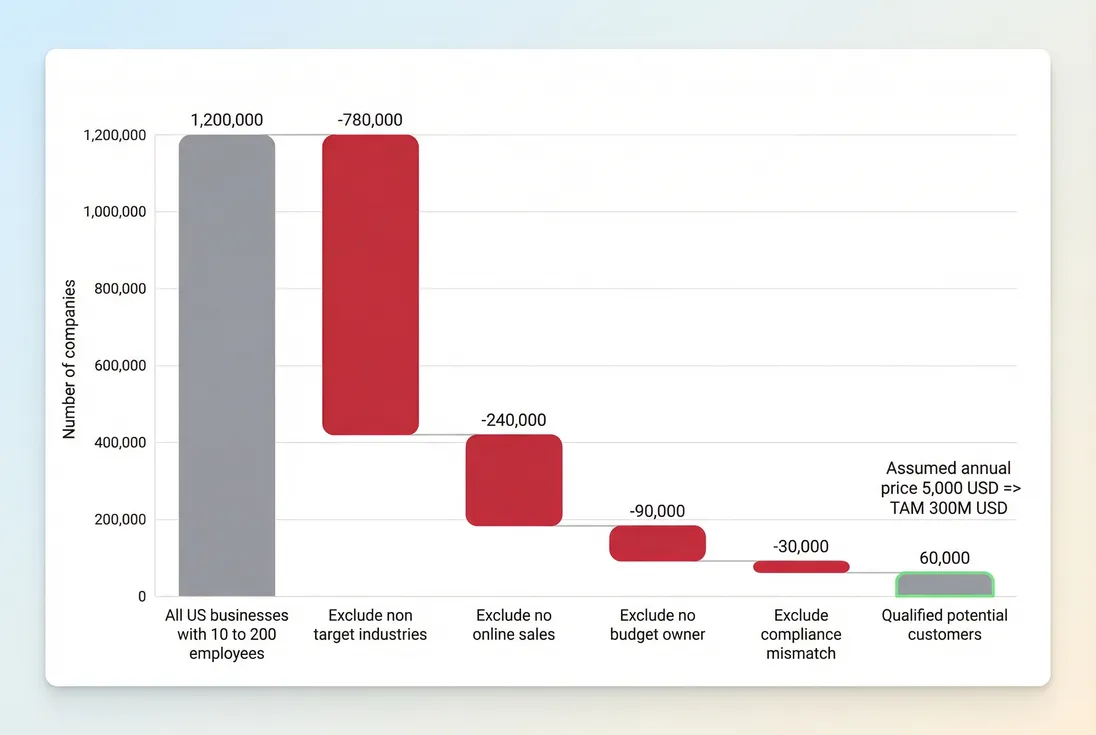

Bottom-up TAM (most practical)

Count the customers in your defined market, then multiply by realistic annual revenue per customer.

If you sell subscriptions, "annual revenue per customer" should reflect your expected pricing and packaging, often approximated by ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account) or ASP (Average Selling Price)—but using market-appropriate values, not your best-case enterprise deals.

Example (B2B SaaS, tight ICP):

- Target buyers: US e-commerce brands with $5M–$100M GMV

- Count of eligible brands: 48,000

- Expected annual contract value for that segment: $6,000/year

So TAM ≈ $288M per year (as a revenue pool), under these assumptions.

Founders mess this up by letting one variable silently drift:

- "Potential customers" becomes "all businesses with a website"

- "Annual revenue per customer" becomes "our highest tier price"

Top-down TAM (useful, but risky)

Start with an industry number (research report), then assume a share.

This is fast, but it often breaks because:

- Reports mix software + services

- Category boundaries are vague

- You inherit someone else's assumptions about adoption and pricing

Top-down is best used as a sanity check, not your primary model.

Value-theory TAM (pricing-led)

Estimate the economic value you create and what portion you can charge for.

This helps when:

- You're creating a new category

- Pricing is usage-based or outcome-based (see Usage-Based Pricing)

- Your product replaces headcount or reduces risk

But value-theory only works if you can defend willingness-to-pay with real evidence (pilots, win/loss notes, procurement feedback).

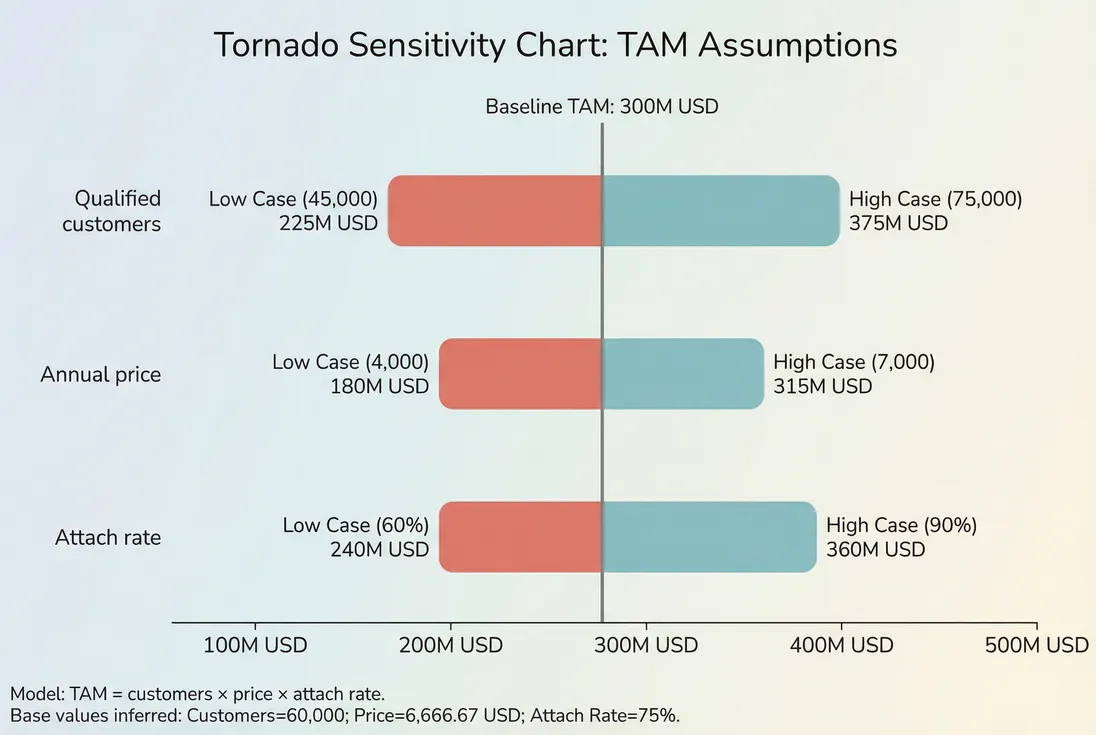

What drives TAM (the levers)

TAM is a model made of assumptions. Your "number" is only as good as the inputs. In SaaS, TAM usually moves because of changes in market definition, price, or eligibility.

1) ICP and eligibility filters

Your TAM grows or shrinks when you change who qualifies:

- Company size (employees, revenue, GMV)

- Industry (vertical focus)

- Tech stack (Shopify vs custom, Salesforce vs HubSpot)

- Geography and language

- Compliance requirements (HIPAA, SOC 2, GDPR)

A common pattern: founders start broad, then narrow after learning who retains well (see Cohort Analysis and Retention). That usually reduces TAM but improves business quality.

2) Pricing and packaging

Your pricing model directly scales TAM if customer counts stay constant.

"Attach rate" matters when not every eligible customer will buy (for example, only companies with a certain workflow pain).

Pricing changes that affect TAM:

- Moving from a $49 plan to $99 (if demand holds)

- Adding an enterprise tier that raises ASP (Average Selling Price) in a segment

- Switching to per-seat pricing (see Per-Seat Pricing) that scales with customer size

Be careful: raising "price" in the TAM model without evidence is the easiest way to create fantasy markets. Use willingness-to-pay signals and Price Elasticity thinking, even if it's directional.

3) Product scope (use cases)

Adding a real second use case can expand TAM more than a dozen features. Examples:

- You move from "billing alerts" to "revenue workflow automation"

- You add a second buyer persona (finance + revops)

- You support an adjacent vertical with similar needs

This is also where TAM and positioning can get sloppy. If the buyer wouldn't search for you or budget for you under that broader category, your TAM expansion is probably premature.

4) Market maturity and adoption

Even if a customer "could" use your product, they may not buy because:

- The category is new; budgets don't exist yet

- Switching costs are high

- The status quo is good enough

These adoption constraints should usually be reflected by moving from TAM to SAM (Serviceable Addressable Market) and SOM (Serviceable Obtainable Market), rather than inflating TAM.

How founders use TAM in real decisions

TAM is most valuable when it forces tradeoffs: where to focus, how to price, and what growth motion is viable.

Decide your GTM motion

A small TAM with high ACV can still be great—if your sales motion matches.

Use TAM together with:

- Sales Cycle Length

- CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost)

- CAC Payback Period

- ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue) targets

Practical interpretation:

- If your TAM depends on thousands of small accounts, you need a scalable channel (PLG or efficient inside sales).

- If your TAM depends on a few hundred large accounts, you need enterprise discovery, procurement readiness, and strong retention economics.

The Founder's perspective

TAM should change your hiring plan. If your realistic SAM supports only a $20M business, hiring a VP Sales and building a 10-rep team "for the future" is usually a cash burn trap.

Sanity-check revenue targets with required share

A simple check prevents years of mismatch between ambition and reality.

If you need an implausible share of SAM, you have three options:

- Expand SAM (new segment, geography, use case)

- Raise achievable price (through packaging or moving upmarket)

- Reduce targets (or accept a smaller outcome)

Example

| Item | Value |

|---|---|

| Target ARR (5–7 years) | $50M |

| TAM (broad category) | $1.2B |

| SAM (your ICP + geos) | $250M |

| Required share of SAM | 20% |

A 20% share might be possible in a winner-take-most market, but in most SaaS categories it's a red flag unless you have a clear distribution advantage.

Pressure-test pricing strategy

TAM is a good forcing function for pricing because it highlights where revenue pool is coming from.

If your TAM only looks big when you assume low price and massive volume, you're betting on:

- cheap acquisition channels

- low support costs

- low churn

That's a fragile plan if your product requires high-touch onboarding or if retention is mediocre (see Logo Churn and NRR (Net Revenue Retention)).

Conversely, if your TAM depends on high price, you need:

- a credible ROI story

- proof you can sell and retain at that price point

- lower churn tolerance (because each lost logo is expensive)

Guide roadmap and expansion bets

A TAM model can tell you where expansion is worth doing:

- New vertical: adds X customers at Y price

- New geography: adds X customers but increases compliance and support cost

- Moving upmarket: fewer customers, higher ASP, longer sales cycle

This pairs well with unit economics frameworks like LTV (Customer Lifetime Value) and LTV:CAC Ratio.

When TAM breaks (common mistakes)

Most TAM errors come from one of these failure modes:

Mixing TAM with "anyone who could"

If your definition includes customers who could theoretically use it but would never budget for it, you're counting "interest" instead of "addressable."

Fix: define addressable as "has the problem, has the budget, and has a path to purchase."

Double-counting revenue pools

This happens when you add multiple segments that overlap (for example, counting the same company in "mid-market" and "Shopify Plus," or counting multi-product bundles twice).

Fix: ensure segments are mutually exclusive, then sum.

Using list price instead of realized price

Realized price includes discounts, downgrades, and packaging reality (see Discounts in SaaS). A TAM based on list price will overstate revenue pool if your market expects discounts.

Fix: model price as what you can consistently win at for that segment, not your price page.

Confusing big TAM with easy growth

A market can be enormous and still hard:

- entrenched incumbents

- high switching costs

- long procurement cycles

- fragmented buyers

Fix: treat TAM as space available, then use SAM/SOM plus pipeline and retention data to judge accessibility.

The Founder's perspective

If your TAM slide makes you feel safe, you're probably using it wrong. A good TAM model makes you uncomfortable in specific ways—by revealing distribution constraints and forcing a focused wedge.

How to keep TAM useful over time

You don't need to "track" TAM weekly. You do need to version it like a strategic model.

Update TAM when:

- You change pricing/packaging materially

- You add a new buyer persona or segment

- You expand geography

- You move upmarket/downmarket

- Win/loss evidence contradicts assumptions

A simple TAM review cadence

- Quarterly: sanity check assumptions (counts, price points, exclusions)

- Annually: rebuild from scratch with new learnings and refreshed data sources

The signals that justify expanding TAM

Don't expand TAM because you want a bigger story. Expand because reality supports it:

- Higher ASP achieved repeatedly in a segment (see ASP (Average Selling Price))

- Retention holds at the higher price (see GRR (Gross Revenue Retention) and NRR (Net Revenue Retention))

- Sales cycle remains manageable (see Sales Cycle Length)

- CAC and payback still work (see CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost) and CAC Payback Period)

Practical benchmarks and rules of thumb

These aren't hard rules, but they prevent common founder mistakes:

- If TAM only works at perfect pricing, it's not addressable. Assume competitive pressure and discounting exist.

- If required share of SAM is above ~10–15%, be extra skeptical. You may still win, but you need a clear distribution edge or a wedge that expands over time.

- If your SOM depends on outbound scaling, validate sales efficiency early. Watch Win Rate and Sales Efficiency alongside CAC/payback.

- If TAM looks huge but retention is weak, the market might not value the product. TAM doesn't fix churn (see Customer Churn Rate and MRR Churn Rate).

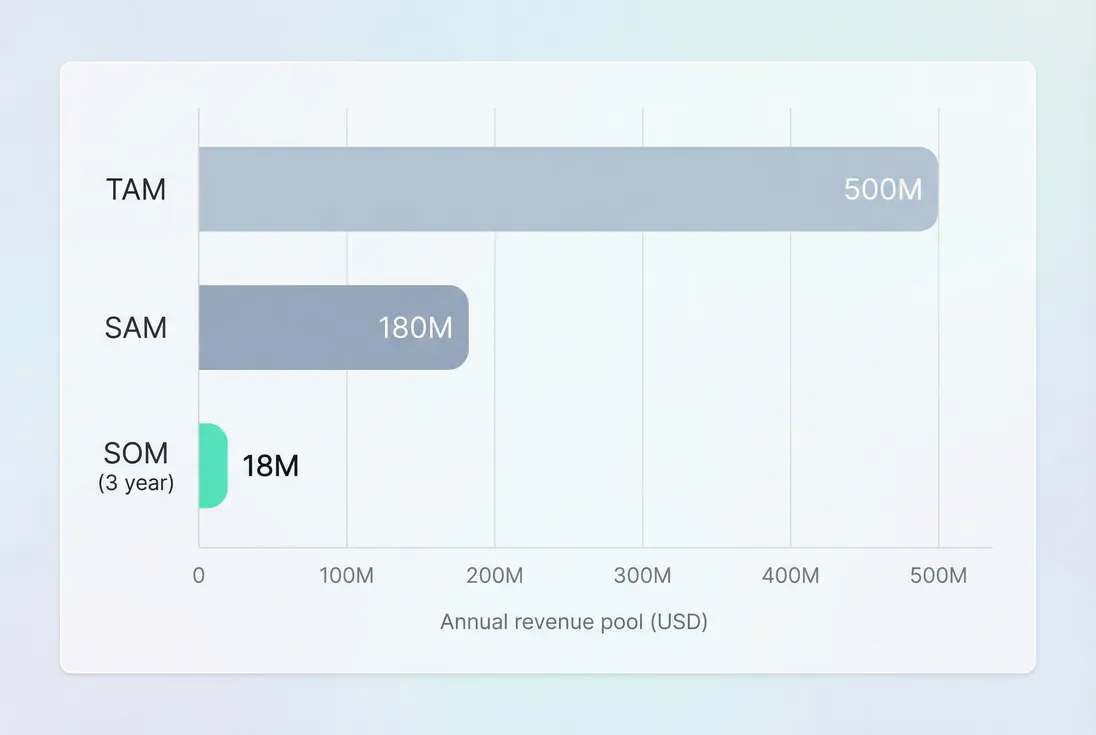

TAM, SAM, SOM: keep them consistent

A clean way to think about it:

- TAM: everyone who could buy within a broad market definition

- SAM: everyone you can serve given product constraints (segment, geo, compliance)

- SOM: what you can realistically capture in a defined time horizon given distribution and competition

If these three aren't consistent, your strategy will be inconsistent too. When in doubt, start with a defensible bottom-up SAM, then expand outward.

Key takeaway

TAM is not a vanity number. It's a strategic constraint: a quantified statement of who you're building for and what they can pay. Build it bottom-up, pressure-test the assumptions, and use it to make decisions about GTM, pricing, and focus—then keep it honest by versioning it as you learn.

Frequently asked questions

There is no universal cutoff, but you want a TAM that can support your long-term revenue ambition without requiring unrealistic market share. If you need 20 to 30 percent of your serviceable market to hit your plan, the market is likely too tight. Use TAM with SAM and SOM to sanity-check ambition.

Lead with SAM and SOM for credibility, and include TAM as context. TAM answers what is possible in the broadest definition, while SAM shows the slice you can actually serve with your product, geography, and compliance. Investors discount hand-wavy TAM, but they reward clear constraints and a realistic wedge.

For early-stage SaaS, bottom-up TAM is usually most defensible: count a specific buyer set and multiply by a realistic annual price for what you sell today. Top-down industry reports can be useful for context, but they often mix categories, include services, or assume adoption you cannot capture.

Yes, but treat it as a model update, not a monthly metric. TAM changes when your ICP expands, you add new geographies, move upmarket or downmarket, change packaging or pricing, or your product becomes applicable to new use cases. Document assumptions so the changes are explainable.

Run a market share sanity check: divide your long-term target ARR by your SAM, not TAM, and ask if the required share is plausible given incumbents, distribution, and switching costs. If you cannot describe a credible path to that share, your TAM likely includes customers who will not buy.