Table of contents

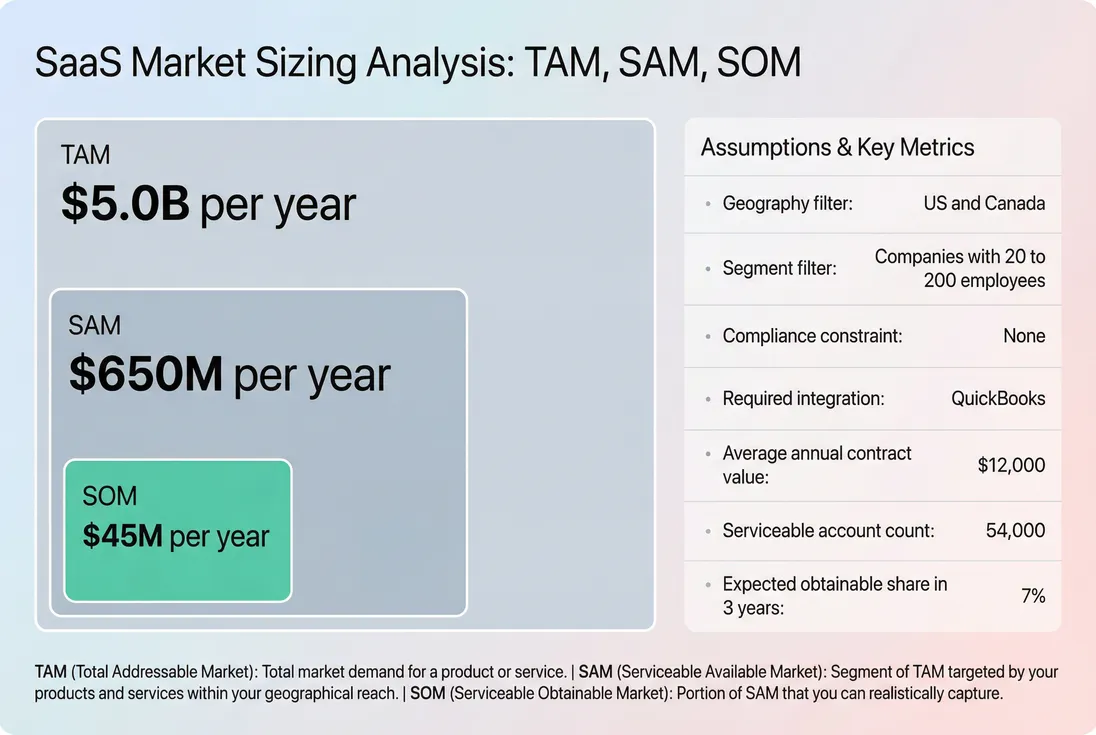

SAM (serviceable addressable market)

SAM is the fastest way to find out whether your growth plan is even possible. If your SAM can't support your target ARR without implausible market share, the fix isn't "try harder"—it's changing your segment, pricing, product scope, or go-to-market.

SAM (Serviceable Addressable Market) is the portion of the market you can realistically serve with your current product and go-to-market constraints—typically defined by who you sell to, where you can sell, and what you can actually support and deliver.

What SAM actually includes

Founders often treat SAM as "TAM but smaller." In practice, SAM is a capability and focus statement:

- Customer definition: your ICP (industry, size, complexity) and buying center.

- Geography: where you can sell/support today (language, time zones, payments, taxes).

- Product readiness: must-have features for that segment (security, permissions, workflows).

- Compliance and risk: regulatory requirements (SOC 2, HIPAA, GDPR), procurement realities.

- Integrations and ecosystem: systems you must connect to (ERP/accounting/SSO).

- Support and delivery model: onboarding burden, implementation time, service capacity.

- Price feasibility: what that segment can pay given your value and competition.

This is why SAM is different from TAM (Total Addressable Market). TAM ignores most constraints. SAM is where constraints become real.

The Founder's perspective: If your SAM definition doesn't change what you build, who you hire, or which leads you reject, it's not operational. A good SAM forces tradeoffs—especially on ICP, integrations, and the minimum security/compliance bar.

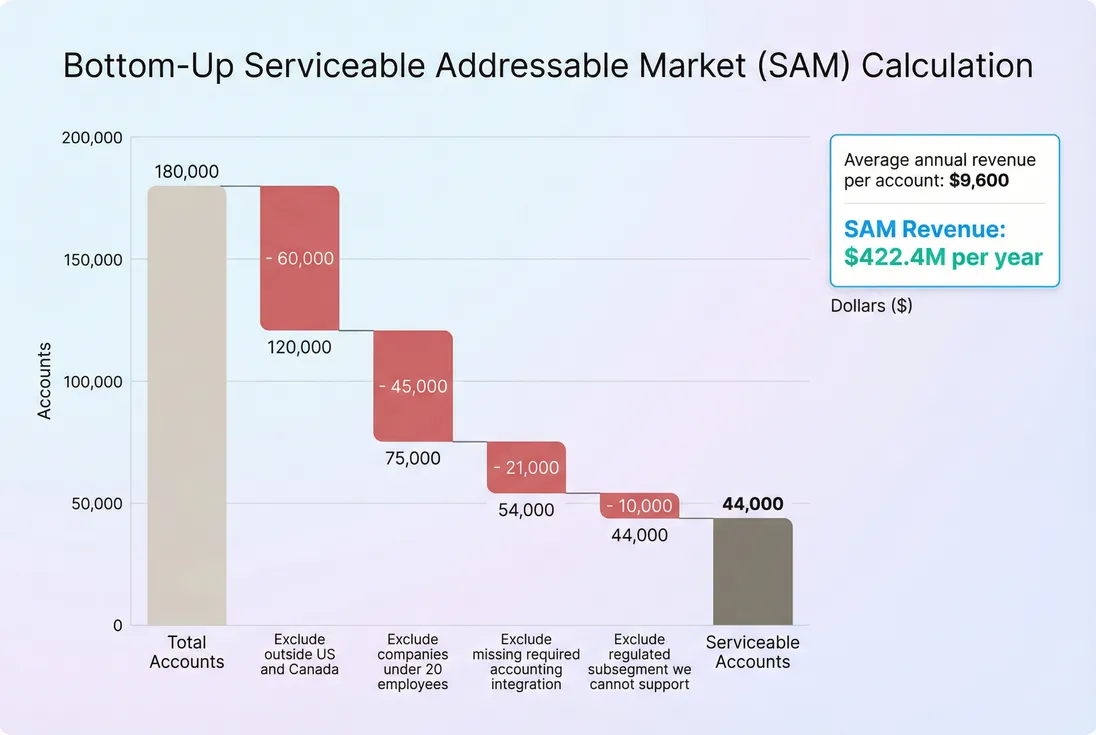

How to calculate SAM (bottom-up)

You'll see three common approaches: top-down, bottom-up, and value-based. For operating decisions, bottom-up is the most useful because it connects directly to your funnel, pricing, and capacity.

The core SAM equation

You can express SAM in accounts and in revenue.

Customer-count SAM:

- "How many accounts exist that we can serve?"

Revenue SAM:

- "If we priced and sold to all serviceable accounts, what annual recurring revenue would that represent?"

A practical revenue SAM formula is:

If you track revenue per account monthly, you can translate it into annual terms:

(See ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account) for how ARPA behaves under plan changes, upgrades, and discounting.)

A step-by-step bottom-up build

Start with a known universe.

Example: "All US and Canada companies in construction with 20–200 employees."Apply serviceability filters.

These are not "nice to haves." They are "we cannot sell without this."- Required integrations (e.g., QuickBooks)

- Security/compliance requirements you can meet today

- Buyer maturity (e.g., must already use a modern payroll system)

- Language/currency/payment rails you support

Estimate realistic average revenue per account.

Use today's pricing or the pricing you can defend with evidence (pilot results, churn behavior, sales calls). Be conservative with enterprise assumptions unless you've proven enterprise motions (procurement, security reviews, implementation).Calculate revenue SAM and sanity-check it.

Compare against:- Current ASP (Average Selling Price) and discounting patterns

- Sales cycle length realities (see Sales Cycle Length)

- Your ability to deliver onboarding and support at that scale

A concrete example (with founder-level usefulness)

Say you sell a workflow SaaS to mid-market agencies.

- Total agencies in target geos: 120,000

- Filter to 10–200 employees: 38,000

- Filter to those using supported billing tools: 24,000

- Filter to those with a clear need (multi-client approvals): 15,000

- Your realistic average annual revenue per account (after discounts): $6,000

Revenue SAM = 15,000 × $6,000 = $90M/year

This number now tells you things TAM never will:

- If you want $30M ARR from this SAM, you're aiming for one-third of the entire serviceable market—hard unless the category is consolidating and you're the winner.

- If you want $30M ARR without heroic share, you likely need to expand SAM (new segment, new geography, new use case) or move upmarket on pricing/packaging.

How big does SAM need to be?

There is no universal benchmark because the "required SAM" depends on:

- Your target ARR and time horizon

- Your retention and expansion motion (see NRR (Net Revenue Retention) and GRR (Gross Revenue Retention))

- Your selling motion and unit economics (see CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost) and CAC Payback Period)

But founders still need a practical gut-check. Here's a useful way to frame it: what share of SAM does your plan require?

Guideline: if your plan requires more than 10–15% share of SAM within a few years, you should assume you'll need at least one of:

- meaningfully higher ARPA (pricing/packaging),

- a second segment (new ICP),

- a new geography,

- a new channel that changes distribution economics,

- or strong expansion that reduces dependence on new logos.

Practical sizing table

| Goal style | What "enough SAM" often looks like | What to check first |

|---|---|---|

| Bootstrapped, profitable niche | $10M–$50M revenue SAM can work | Can you reach buyers efficiently and keep churn low? (Customer Churn Rate) |

| Mid-scale SaaS ($5M–$20M ARR) | $100M–$500M revenue SAM is usually comfortable | Is ARPA real or aspirational? (ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account)) |

| Venture-scale ambition | Often $1B+ revenue SAM, or credible SAM expansion path | Do CAC payback and sales cycle support fast scaling? (Burn Multiple) |

These are not rules—they're friction tests. A smaller SAM can still produce a great outcome if your margins and retention are exceptional, or if expansion meaningfully increases customer value over time.

The Founder's perspective: Investors ask about TAM. Operators should obsess over SAM because it sets the ceiling on how many "good customers" you can acquire before you're forced to expand scope. If you hit that ceiling early, growth slows and CAC usually rises.

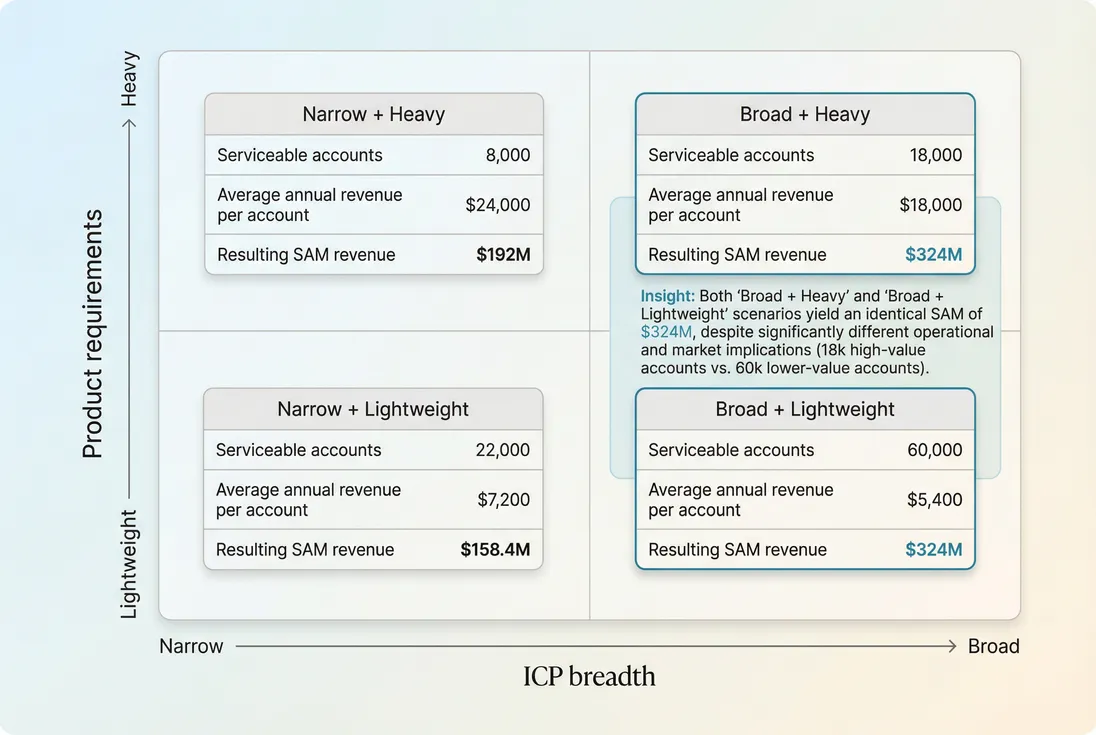

What drives SAM up or down

SAM changes when your serviceability changes, not just when the world gets bigger.

Common levers that increase SAM

New geography or language

- Adding EU means payments, VAT, privacy expectations, and support coverage. (See VAT handling for SaaS for what can bite you operationally.)

New segment you can truly serve

- Example: moving from "agencies" to "professional services firms," if workflows and compliance hold.

Integration coverage

- Supporting the dominant system of record in your space can unlock a large part of the market that was "not serviceable."

Security and compliance readiness

- SOC 2 or SSO can unlock larger customers. But it also changes sales cycles and support expectations.

Packaging and pricing architecture

- Not just "raise prices," but aligning value metrics (see Per-Seat Pricing and Usage-Based Pricing) so you can serve more customers profitably at different sizes.

Changes that shrink SAM (and why that's not always bad)

- Narrowing your ICP after learning who retains and expands

- Dropping a low-quality segment with high support burden

- Raising minimum plan price to match support costs

A smaller SAM can be a strategic win if it improves unit economics and reduces churn. Your SAM model should reflect who you can serve profitably, not just who you can technically sell to.

How founders use SAM to make real decisions

SAM is most valuable when it prevents wasted quarters. Here are the most common decisions it should directly influence.

1) Picking an ICP that can sustain growth

If your current ICP yields high retention but tiny SAM, you have three options:

- Commit to a niche (optimize margins, keep team lean).

- Move upmarket (raise ARPA, accept longer sales cycles).

- Add an adjacent ICP (expand SAM while reusing product strengths).

Don't skip straight to "adjacent ICP" without proving you can win repeatedly in the first one. Use early retention and expansion signals (see Cohort Analysis) to decide whether your niche is a foundation or a trap.

2) Setting realistic ARR targets

A clean way to translate SAM into target realism:

- If your 3-year plan implies you must win 20% of SAM, your plan is really a category domination plan.

- If your plan implies 2–5% of SAM, it may be feasible with strong execution.

This also shapes hiring:

- High share targets usually require heavier sales capacity, sharper positioning, and better distribution—often meaning higher burn and tighter tracking of capital efficiency (see Capital Efficiency).

3) Deciding whether to build or integrate

SAM is often constrained by "must-have" integrations and compliance. A practical rule:

- If lack of an integration excludes a large portion of serviceable accounts, it's not a feature request—it's a market-access requirement.

Use SAM math to rank roadmap items:

- "This integration increases serviceable accounts by 40%" beats "this feature might increase conversion."

4) Pricing and packaging without self-sabotage

Pricing can increase revenue SAM, but it can also decrease serviceable accounts if you price above what the segment can sustain.

When evaluating pricing changes, model both:

- change in average annual revenue per account, and

- change in serviceable accounts at that price.

Also account for discounting reality (see Discounts in SaaS). If you size SAM on list price but always close at 25% off, your SAM is inflated.

5) Choosing a go-to-market motion

SAM should inform Go To Market Strategy because each motion has different constraints:

- Sales-led: You can access higher ARPA, but sales cycle length and implementation can reduce serviceability.

- Product-led: You can access more accounts, but willingness to self-serve and support load become constraints.

A "large SAM" that requires procurement-heavy selling might be operationally smaller for a tiny team than a "smaller SAM" that buys self-serve quickly.

The Founder's perspective: A common failure mode is building an enterprise-ready product for an SMB-go-to-market team—or running a PLG motion in a market where every deal requires security review. Your SAM definition should match your GTM reality.

When SAM breaks (and how to fix it)

SAM gets misleading when assumptions hide real constraints. Watch for these red flags.

Red flag 1: You're counting customers who can't buy

Examples:

- You require SOC 2 to close, but you don't have it yet.

- Your buyer needs SSO/audit logs and you're "planning it."

Fix: separate SAM today vs SAM after roadmap and attach dates.

Red flag 2: Your ARPA assumption isn't proven

If your SAM depends on enterprise ARPA but your current motion closes small deals, your SAM is aspirational.

Fix: build SAM with current ARPA, then a second scenario with the changes required to earn higher ARPA (sales cycle, onboarding, product depth).

Red flag 3: You confuse "serviceable" with "reachable"

Reachability is closer to SOM. If your go-to-market can't reach a segment efficiently, it may still be in SAM (you could serve them), but it won't show up in results.

Fix: pair SAM with SOM planning (see SOM (Serviceable Obtainable Market)) and validate with funnel metrics like Win Rate and Sales Cycle Length.

Red flag 4: You ignore churn and expansion

SAM sets the ceiling on new logos, but your ARR trajectory depends heavily on retention and expansion.

Fix: connect SAM planning to retention reality using MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue) movements and retention metrics like Net MRR Churn Rate.

A simple SAM worksheet you can reuse

Answer these in one page. If you can't, your SAM isn't ready to guide decisions.

- ICP definition: who exactly is included (industry, size, buyer)?

- Serviceability constraints: what must be true to sell and retain?

- Serviceable account count: what is your defensible estimate and source?

- Average annual revenue per account: what is your proven range?

- SAM today vs later: what changes it, and what must you build to unlock it?

- Implied share vs ARR target: what share does your plan require?

If you do this honestly, SAM becomes less about storytelling and more about preventing strategic waste.

Key takeaways

- SAM is the market you can actually serve, given real constraints—not the market you wish you could serve.

- Bottom-up SAM is the most operational: serviceable accounts × defensible annual revenue per account.

- Use SAM to stress-test ARR plans: if required share is too high, you need higher ARPA, broader serviceability, or a longer timeline.

- SAM changes when your capabilities change (integrations, compliance, geography, packaging), not just when the world grows.

Frequently asked questions

TAM is everyone who could ever use a solution like yours. SAM is the portion you can realistically serve given your product, geography, compliance, integrations, and go-to-market constraints. SOM is the portion of SAM you can realistically win in a defined time window with your budget, team, and channel performance.

Use both. Customer-count SAM helps with pipeline math and coverage planning. Revenue SAM helps you sanity-check growth goals and valuation narratives. If forced to pick one, use revenue because pricing, packaging, and expansion meaningfully change outcomes even when account counts stay constant.

It depends on your ambition, pricing, and retention. A $20M SAM can support a great bootstrapped business if margins and retention are strong. For venture-scale outcomes, founders typically need a much larger SAM or a credible expansion path that grows SAM over time through new segments, geographies, or use cases.

Revisit SAM whenever your ICP, pricing, or distribution changes, and at least quarterly in the first two years. Early on, your biggest risk is building around assumptions. As you learn your true ARPA, sales cycle, and win rate, your SAM model should get narrower, more defensible, and more useful for decisions.

The big ones are counting buyers you cannot serve yet, assuming unrealistic price points, ignoring adoption constraints like compliance and integrations, and treating SAM as a pitch number rather than an operating tool. A "smaller but real" SAM is more actionable than an inflated number that won't guide focus.