Table of contents

Refunds in SaaS

Refunds are one of the fastest ways to quietly destroy capital efficiency: you already paid to acquire the customer, you already spent support time, and then you hand the cash back. If refunds drift up even a little, your growth can look fine while your payback and runway get worse.

A refund in SaaS is money you return to a customer after you already collected a payment, usually tied to cancellation, dissatisfaction, billing mistakes, or policy (like a money-back guarantee). Refunds are not the same as discounts, credits, or chargebacks—and mixing them together is how founders end up "debugging" the wrong problem.

What refunds reveal about fit

Refunds are a blunt metric, but they're high-signal because customers only ask for money back when at least one of these is true:

- They didn't get value fast enough (time-to-value is too long for your promise).

- They didn't understand what they bought (positioning, packaging, or pricing page clarity).

- They experienced friction or failure (bugs, uptime, integration issues).

- They didn't mean to buy (billing UX confusion, renewal surprises, fraud).

- Your policy encourages it (generous guarantees without guardrails).

Refunds are also one of the cleanest ways to catch "bad growth." If new signups are rising but refunds are rising faster, you're often pulling in lower-intent customers or creating new confusion.

The Founder's perspective

If refunds rise while signups rise, don't congratulate yourself on top-of-funnel. Assume your effective CAC just increased and your payback just got longer. Fix the leak before you scale the spend.

What counts as a refund

Getting definitions right matters because refunds touch cash, taxes, revenue recognition, and customer experience.

Refunds vs credits vs discounts

- Refund: cash goes back to the customer (card reversal, ACH return, etc.).

- Credit: value is granted without sending cash (credit note, extra month free, account balance). Credits reduce future collections but may not show up as a "refund."

- Discount: price reduction at time of purchase or renewal. It's not a refund because the cash was never collected. See Discounts in SaaS for how discounts affect revenue metrics.

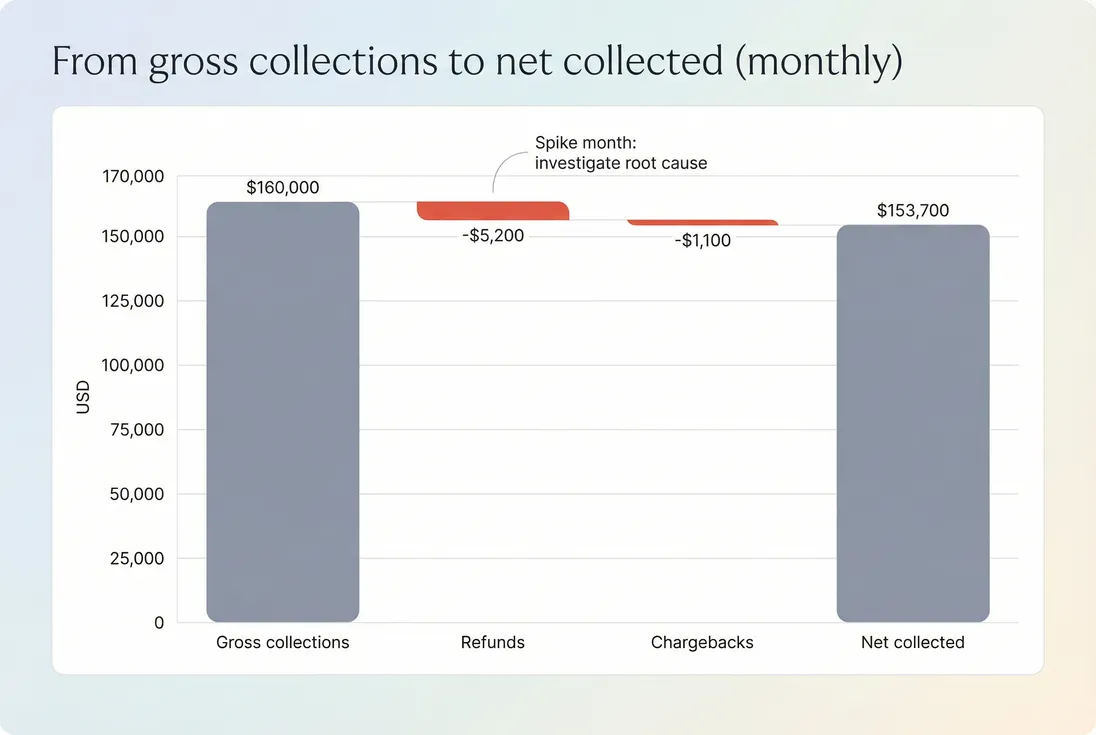

Refunds vs chargebacks

A chargeback is initiated by the customer's bank, not by you. It comes with different risk and operational overhead (fees, fraud signals, potential account restrictions). Track it separately; see Chargebacks in SaaS.

Partial refunds and proration

Refunds are often partial (prorated) when customers cancel mid-cycle, or when you compensate for downtime. Decide upfront whether you want:

- Prorated refunds (cash back),

- Prorated credits (service credit),

- No proration (common in month-to-month; more sensitive for annual).

For annual prepay, refunds can be "all-or-nothing" (strict policy) or prorated (customer-friendly, but exposes you to higher refund liability).

Tax and VAT implications

If you collected sales tax or VAT, a refund often requires refunding the tax portion too and maintaining correct reporting. This gets messy quickly across regions—see VAT handling for SaaS.

How to measure refunds cleanly

The goal is simple: measure refunds in a way that helps you make decisions, without contaminating subscription metrics like MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue).

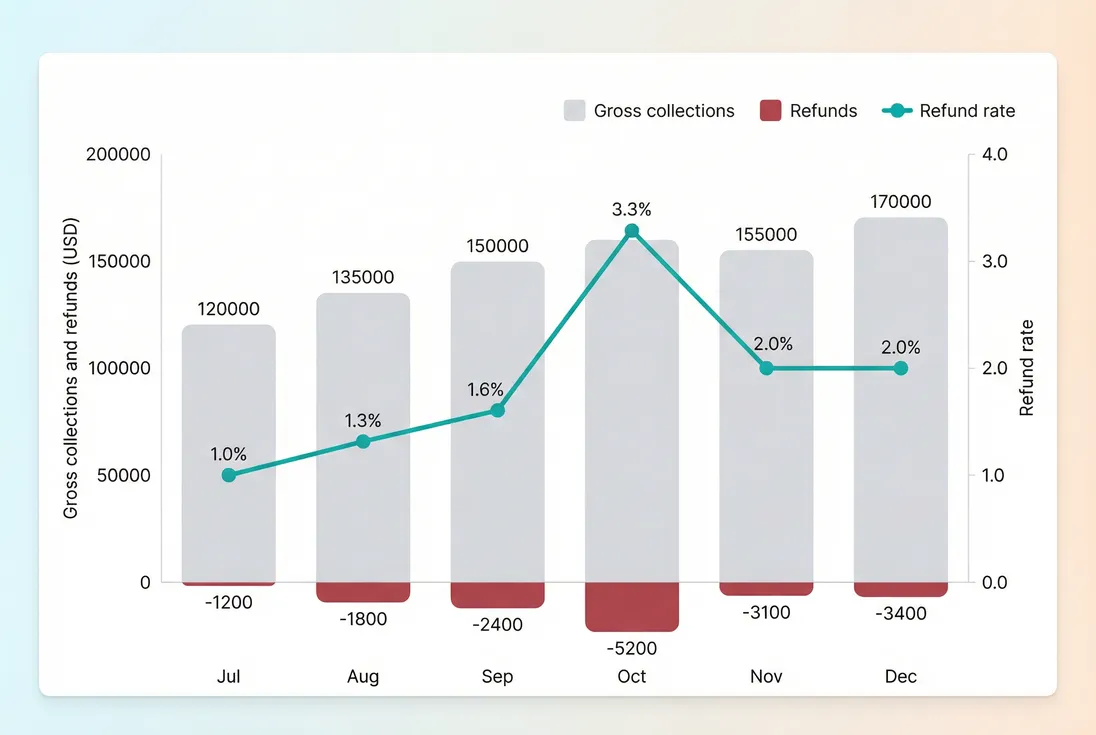

Core refund rate (dollars)

Use a dollars-based rate first; it ties directly to cash impact.

Practical notes:

- Use gross collected (cash-in) as the denominator, not recognized revenue. Refunds are a cash event first.

- Keep the period consistent (monthly is typical).

- Exclude chargebacks from refunds; they are different operationally.

Refund incidence (count)

This catches "lots of small fires" even when dollar impact looks small.

Count-based incidence is useful when:

- You have many low-priced plans (where dollars hide volume),

- Fraud or "oops purchase" behavior is common,

- You're changing onboarding or trial-to-paid flows.

Net collections (cash reality)

If you want one number that reflects what actually stayed in your bank after reversals:

This is not a replacement for revenue metrics, but it is great for cash planning and spotting billing turbulence that affects Burn Rate and runway.

Segment the metric or it won't help

A blended refund rate is often useless. Segment at least by:

- Plan or price point (refund patterns differ dramatically by ASP; see ASP (Average Selling Price))

- Acquisition channel (paid social vs search vs partner)

- Customer size (self-serve vs sales-assisted; see ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account))

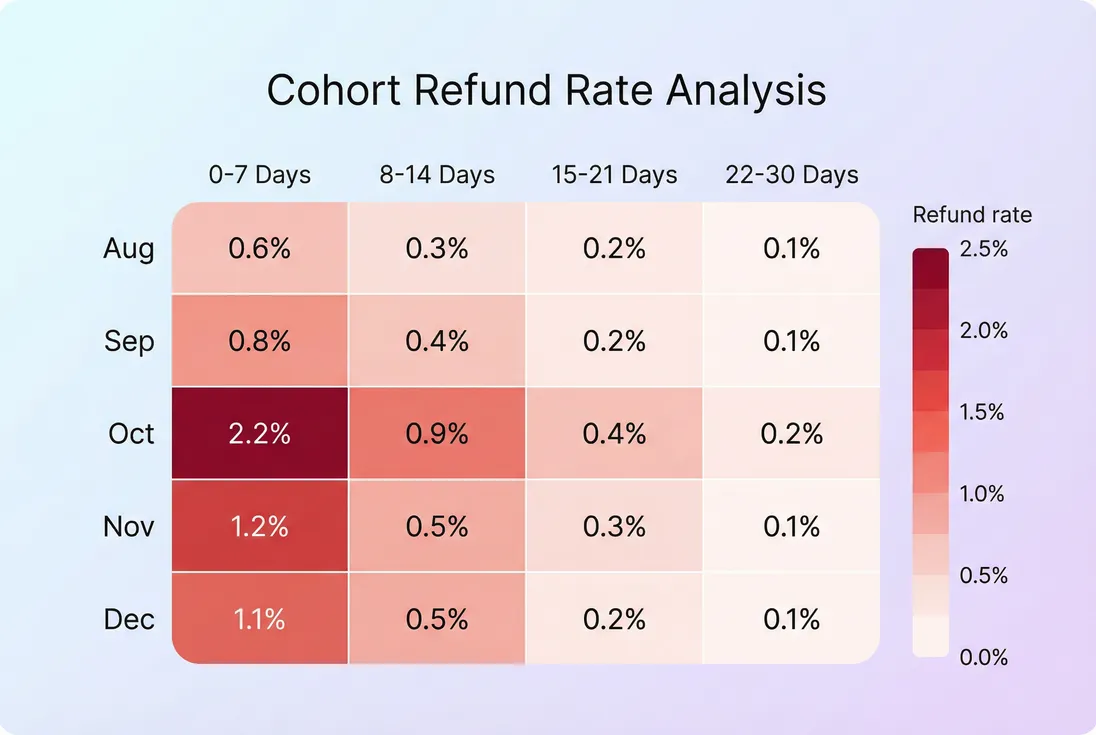

- Time since purchase (first 7 days, 30 days, 90 days)

You're typically looking for one of two patterns:

- Early refunds: expectation mismatch or slow activation.

- Later refunds: billing disputes, renewal surprise, or account changes.

How refunds affect MRR and retention

Refunds are where SaaS teams accidentally "double count pain": once in MRR churn and again in refunds, or worse, they miss it entirely.

Refunds are not automatically MRR churn

MRR is a state metric tied to active subscriptions. A refund is a transaction event. They often happen together, but not always.

Common scenarios:

Cancel + refund

Customer cancels and requests money back (often within a guarantee window). Here you have:- A subscription ending (likely churn),

- A cash reversal (refund).

Refund without cancellation

You issue a refund for downtime or goodwill, but the customer stays active. Here:- MRR may remain unchanged,

- Refund rate increases,

- Revenue recognition changes.

Cancellation without refund

Customer cancels at period end with no refund. Here:- MRR churn increases,

- Refunds do not.

If you're monitoring retention, keep your retention analysis separate (see GRR (Gross Revenue Retention) and NRR (Net Revenue Retention)), and treat refunds as a parallel quality and cash signal.

The Founder's perspective

If retention is stable but refunds rise, you likely have billing confusion, service credits turning into cash refunds, or a policy/ops problem—not a product-market-fit collapse. Don't rip up your roadmap until you validate where refunds are coming from.

Refunds can distort invoice-based MRR

Some teams compute MRR from invoices or cash receipts. In that setup, refunds show up as negative revenue movements and can create phantom volatility.

A safer approach:

- Use subscription state for MRR and churn (the customer is active or not),

- Track refunds as a separate "reversals" layer you reconcile to cash and recognized revenue.

For revenue accounting concepts that influence how refunds appear, see:

Annual plans: refunds are bigger and weirder

Annual prepay refunds are painful because:

- They're lumpy (one refund can erase many months of net new cash),

- They create ambiguity: are you refunding unused service, or "breaking" a contract?

Operationally, annual refunds also tend to come from:

- Procurement/legal disputes,

- Missing promised capabilities,

- Implementation failures.

That's why you should track annual refunds separately from monthly self-serve refunds.

How to diagnose refund spikes

When refunds jump, founders often guess wrong (usually "product is bad"). Refund spikes are more often caused by a specific change in acquisition, billing, or policy.

Start with three splits

By time-to-refund

Plot refunds by "days since first payment." If the spike is heavily in days 0–7, it's usually expectation-setting, onboarding, or accidental purchases.By plan and price

If the spike is concentrated in one plan, you may have:- Confusing packaging,

- A broken entitlement or feature gate,

- A pricing page mismatch.

By acquisition channel or campaign A new channel can bring "tourists" who buy, bounce, and refund. If you're scaling spend, this directly degrades CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost) and CAC Payback Period.

Then look for operational triggers

Refund spikes commonly follow:

- Pricing or packaging changes (especially when existing customers are surprised at renewal)

- Trial changes (shorter trial, earlier paywall)

- Billing UX changes (new checkout, new invoice emails)

- Incident or outage (refunds as compensation)

- Policy shifts (introducing a money-back guarantee)

Tie the spike to a timeline of changes. If you can't list changes in the last 30 days, your instrumentation and change log need work.

Use cohort analysis to confirm

A good diagnostic is: "Did newer customers refund more than older customers at the same lifecycle age?" That's exactly what cohorting helps answer. See Cohort Analysis.

How founders reduce refunds (without gaming metrics)

The objective isn't "zero refunds." The objective is: fewer avoidable refunds, fewer abusive refunds, and faster learning when refunds happen.

1) Prevent expectation mismatch

Most early refunds are "this isn't what I thought it was." Fixes that work:

- Make the first value moment explicit on the pricing page and checkout confirmation.

- Replace feature lists with "what you can accomplish in week 1."

- Clarify "who it's for" and "who it's not for."

If you're using heavy discounting to close deals, watch refund rates by discount band; discounts can pull forward bad-fit customers. (See Discounts in SaaS.)

2) Shorten time to value

Refunds in days 0–7 are often an onboarding failure. Typical levers:

- Reduce setup steps before the first meaningful output

- Provide an "aha" template and prefilled data

- Add in-product guidance right before the first critical action

This is also where retention metrics connect. If you improve time-to-value, you usually improve both refunds and early churn. For retention framing, see Voluntary Churn.

3) Fix billing friction (the unsexy win)

A surprising share of refunds are self-inflicted:

- confusing invoice descriptions,

- unclear renewal dates,

- receipts that don't match the product name,

- duplicate charges from retries or multiple workspaces.

Treat billing like product. Monitor:

- refunds tagged "accidental," "duplicate," "didn't mean to renew,"

- refunds clustered right after invoice emails.

If you sell annual contracts or invoice customers, also review Accounts Receivable (AR) Aging—billing process issues often show up as both slow pay and post-payment refund requests.

4) Make policy clear and enforceable

A policy that is generous but vague invites abuse and creates support inconsistency.

Good policy characteristics:

- Specific window (for example, 14 or 30 days)

- Clear eligibility (first-time customers, self-serve only, no overuse)

- Clear method (refund vs credit)

Be careful with "no questions asked" if you sell higher-priced plans; you can end up attracting customers who treat you like a rental.

5) Instrument refund reasons like churn reasons

Refunds are a cancellation moment with extra information: the customer is telling you why they want the money back.

If you already run Churn Reason Analysis, mirror the same approach for refunds:

- Require a reason code (support-selected, not customer free-text only)

- Review top reasons monthly

- Tie each reason to an owner and a fix (product, marketing, support, billing)

The Founder's perspective

A refund is a forced conversation with your market. Don't file it under "support handled." If you can't explain your top three refund reasons and what you changed because of them, you're missing one of the cheapest feedback loops you have.

Benchmarks and operating cadence

Refund benchmarks are messy because they depend on your motion, price, and policy. Still, founders need decision thresholds.

Practical benchmark ranges (monthly)

Use these as starting points, then anchor to your trailing baseline.

| Motion / product type | Typical refund rate (dollars) | What to watch |

|---|---|---|

| Self-serve SMB, low ASP | ~0.5% to 2.5% | Channel mix changes, first-week onboarding |

| PLG with strong trial | ~0.3% to 1.5% | Trial-to-paid friction, accidental upgrades |

| Sales-led mid-market / enterprise | ~0.0% to 0.5% | Contract disputes, implementation failures |

| Consumer-like subscriptions | ~1.0% to 5.0% | Fraud, high-volume refund abuse |

"Investigate now" triggers

Even without perfect benchmarks, these are strong signals:

- Refund rate up 50% or more vs your last 3-month average (see T3MA (Trailing 3-Month Average))

- Refunds concentrated in a new channel or campaign

- Refunds clustered in the first week after purchase

- A single plan driving the majority of refunds

- Refunds increasing while churn stays flat (often billing/policy issues)

How refunds show up in board metrics

Refunds affect:

- Cash (obvious, immediate)

- Payback (your CAC is now amortized over less retained cash)

- Capital efficiency (see Burn Multiple and Capital Efficiency)

- Revenue reporting (recognized and deferred revenue adjustments)

If you report ARR growth (see ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue)), don't let a refund spike create narrative confusion. Explain whether the issue is:

- cancellation-driven (retention problem), or

- refund-driven without churn (billing/service credit problem), or

- both (serious fit or delivery issue).

A simple refund dashboard that works

If you only build one view, make it answer these questions quickly:

- How much did we refund this month (dollars and count)?

- What percent of gross collections was that?

- Where did refunds come from (plan, channel, segment)?

- How fast did refunds happen (days since first payment)?

- Top reasons (and are they changing)?

That's enough to turn refunds from an annoying support artifact into a management signal you can act on—before they quietly wreck payback and cash.

If you want to connect refunds to broader retention health, pair this work with Net MRR Churn Rate and GRR (Gross Revenue Retention), but keep the definitions clean: MRR is subscription state; refunds are cash reversals.

Frequently asked questions

Compare refunds to gross collections and split by segment and plan. A small baseline can be normal in self-serve, but spikes or sustained increases usually mean misaligned acquisition, onboarding issues, or confusing billing. If refunds concentrate in the first 7 to 30 days, treat it as a fit or activation problem.

Benchmarks vary by motion. Self-serve SMB often sees higher refunds because customers buy without sales guidance and expect quick time to value. Sales-led and annual contracts tend to have lower refund rates but can show larger one-off events. Use your own trailing baseline and watch changes after pricing, positioning, or onboarding shifts.

Treat refunds as their own event stream, then map them to churn only when they coincide with a cancellation or downgrade. Refunds affect cash immediately, but MRR should reflect the current subscription state. If you compute MRR from invoices, refunds can create artificial volatility unless you separate subscription changes from billing adjustments.

A refund is voluntary and initiated by you (often after a request). A chargeback is initiated by the customer through their bank and can include fees and higher fraud risk. They behave differently operationally and analytically. Track them separately and review [Chargebacks in SaaS](/academy/chargebacks/) for dispute dynamics and prevention tactics.

Focus on preventing "surprise and regret." Improve expectation-setting on the pricing page, tighten qualification, shorten time to value, and make billing terms obvious. Use prorated credits for edge cases when appropriate, but keep policies consistent. Review refund reasons monthly and tie fixes to product onboarding and support workflows.