Table of contents

One time payments

One time payments can make your "revenue" look great in a bank account while quietly making your subscription business harder to understand. If you don't separate them cleanly, you'll overestimate growth, misread retention, and make bad hiring and spend decisions based on cash that won't repeat.

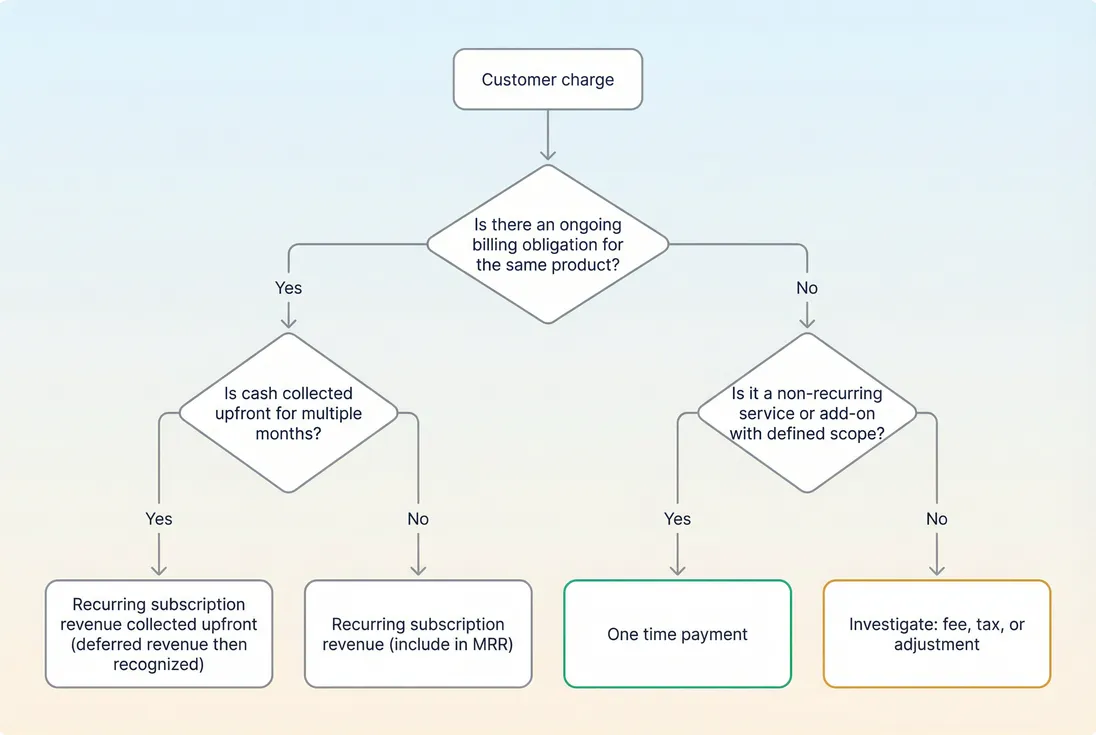

One time payments are charges collected from customers that are not part of a recurring subscription commitment. They're typically billed once (or irregularly) for things like setup, implementation, training, one-off add-ons, overages billed ad hoc, data migration, custom work, or non-recurring fees.

A simple rule: if the customer would not reasonably expect the charge to happen again on a schedule, treat it as one time.

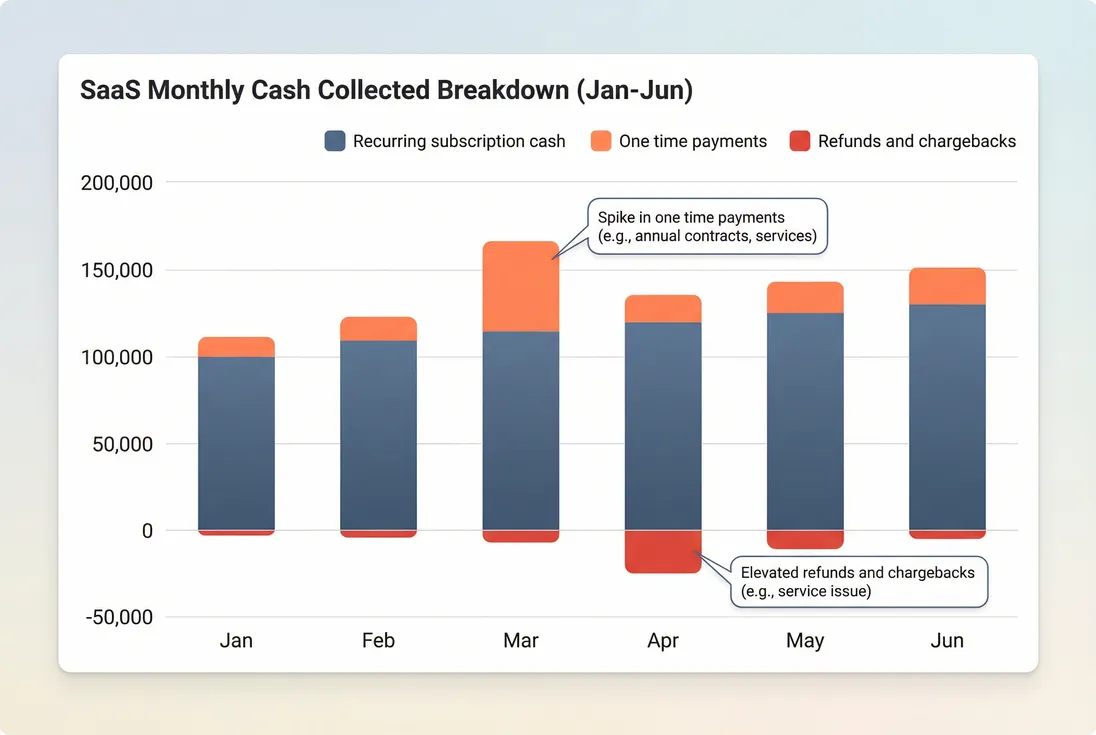

Separate recurring cash from one time payments and refunds so spikes don't masquerade as sustainable growth.

Where one time payments fit

Most SaaS founders already track MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue) and ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue). One time payments sit next to those metrics, but they should not be mixed into them.

Think of your monetization in three buckets:

- Recurring subscription revenue (belongs in MRR/ARR).

- One time payments (non-recurring, irregular).

- Adjustments like refunds, credits, and chargebacks (should reduce whichever bucket they relate to, and be visible).

This separation matters because your core operating questions depend on recurring quality:

- Can I hire ahead of growth?

- What is my CAC Payback Period on subscription gross profit?

- What does retention look like through NRR (Net Revenue Retention) and GRR (Gross Revenue Retention)?

If one time payments are blended into "revenue," those answers get distorted.

The Founder's perspective

If you can't explain last month's growth as "new recurring + expansion minus churn," you will eventually spend like the spike is permanent. One time payments are fine—sometimes great—but they need to be treated like a different fuel source.

What counts (and what does not)

A common mistake is to classify based on invoice cadence ("it was invoiced once, so it's one time"). Instead, classify based on economic intent.

Here's a practical classification table founders can use:

| Item | Usually one time? | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|

| Setup / onboarding fee | Often yes | Helps recover sales and onboarding costs; can boost payback without changing MRR. |

| Implementation / training | Yes | Often higher margin than subscription; can also hide churn if used as a "services crutch." |

| One-off add-on purchase | Yes | Reveals willingness to pay for specific outcomes; input to packaging. |

| Overage billed ad hoc | Depends | If it's predictable usage, consider Usage-Based Pricing and treat as recurring-like (but be consistent). |

| Annual prepayment for subscription | No (cash is one-time, revenue is recurring) | Cash timing differs from revenue timing; relates to Deferred Revenue and Recognized Revenue. |

| Hardware pass-through | Yes, but segment separately | Often low margin; can distort growth and gross margin trends. |

| Contractual recurring add-on billed monthly | No | It's recurring; include in MRR once contracted. |

| Late fees | Yes | Often a symptom: billing friction or customer distress; tie to Accounts Receivable (AR) Aging. |

Two "gotchas" that cause messy reporting:

- Discounting and credits. If you run a one-time credit, do you reduce one time payments, recurring revenue, or both? It depends on what the credit is compensating for. Keep a clear policy; see Discounts in SaaS.

- Taxes and fees. VAT and sales tax collected are not revenue. If you operate internationally, be explicit about tax handling; see VAT handling for SaaS. Payment processor fees are an expense; see Billing Fees.

How to calculate it

At its simplest, one time payments for a period are the sum of non-recurring charges collected in that period.

Use two views: gross (what you charged) and net (what you keep after refunds/chargebacks). Net is what founders should use for planning.

Two additional ratios make the number easier to interpret:

One time share of cash collected

One time revenue per new customer (useful if you charge setup)

Cash vs revenue timing

A founder mistake is to treat "payments" as "revenue" in the accounting sense.

- Payments are cash events.

- Recognized revenue is an accounting view of when value is delivered.

Annual prepay is the clearest example: cash hits once, but revenue is recognized over time (and will often sit in deferred revenue first). If you're using one time payments for cash planning, that's fine—just don't confuse it with sustainable subscription momentum.

The Founder's perspective

If your burn and hiring plan is driven by cash collected, track one time payments explicitly—but make sure your core growth narrative is still MRR and retention. One time cash is a lever, not your engine.

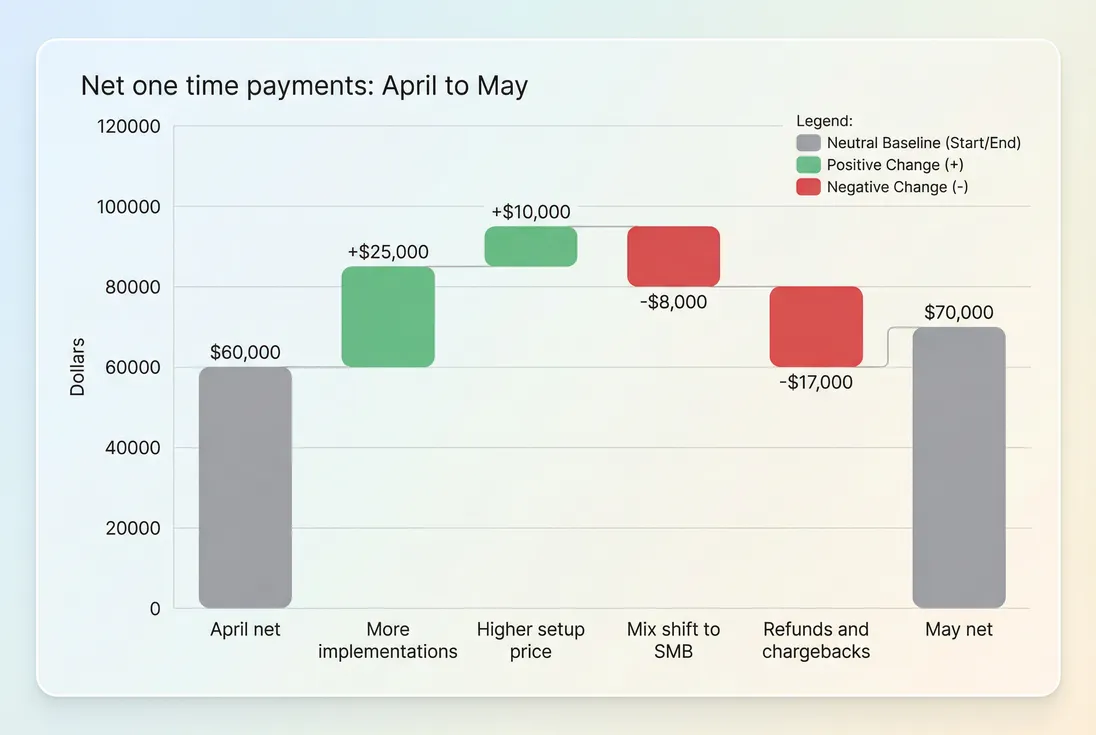

What moves the number

If one time payments change month to month, it's usually one (or more) of these drivers:

1) Volume: how many customers bought one-time items

This is often a function of:

- onboarding capacity (services slots)

- attach rate in sales process

- product complexity (more complexity often creates more services demand)

2) Price: the level of fees charged

A pricing change is easy to see in one time payments, but it can be misleading: you may raise setup fees and reduce conversion, leaving total cash unchanged.

Pricing questions here should tie back to:

- ASP (Average Selling Price) for deal economics

- ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account) to ensure your base subscription still grows

3) Mix: which segments are buying

Enterprise customers often drive higher one time payments (implementation, security review support, migration). If your one time line is rising because enterprise mix is rising, expect:

- longer Sales Cycle Length

- different retention profiles (use Cohort Analysis)

4) Refund and dispute behavior

Refunds can lag by weeks. Chargebacks can lag even more and may cluster by acquisition channel or geography. If net one time payments are volatile, review:

- Refunds in SaaS

- Chargebacks in SaaS

- channel quality (bad traffic often shows up as one-time purchases followed by disputes)

A simple bridge makes one time volatility explainable: volume and pricing up, but mix and refunds pulled net down.

How founders use one time payments

One time payments are most useful when they answer operational questions quickly—especially about cash, margin, and scalability.

Use case 1: Improve CAC payback without gaming MRR

Setup fees and paid onboarding can materially improve cash payback, especially in sales-led motion. But the key is whether the fee is:

- Repeatable (standard package, clear scope)

- Profitable (positive contribution after delivery cost; see Contribution Margin)

- Not a conversion killer (watch win rate and sales cycle)

If you charge a $3,000 onboarding fee, it can shorten payback even if MRR is unchanged—useful when cash is tight and you're managing Burn Rate and Runway.

Use case 2: Spot "services dependency" risk

A high one time line can mean you're really a services company attached to a SaaS product—especially if:

- implementation revenue grows with headcount linearly

- customers require heavy customization to see value

- churn is high without ongoing services

This isn't automatically bad. It's bad when you think you're scaling SaaS but are actually scaling labor.

A quick diagnostic:

- Compare one time payments growth to customer count growth.

- Check whether cohorts with high implementation revenue have better retention (or worse). Use Cohort Analysis.

Use case 3: Decide where to standardize your offering

If one time payments come from the same "custom" work repeatedly, that's a product roadmap signal.

Examples:

- frequent paid data migrations → invest in import tooling

- frequent one-off integrations → build core integrations or an API strategy

- frequent security questionnaires billed as one-off → create a standard enterprise readiness pack

This is where one time payments become a demand map for what customers value outside the base plan.

Use case 4: Keep MRR clean and retention trustworthy

One time payments can hide churn if you let them bleed into "revenue" reporting.

If you're reporting retention metrics (NRR/GRR) or Net MRR Churn Rate to investors, ensure:

- one time charges are excluded from MRR movements

- refunds are attributed to the right bucket (recurring vs one time)

- annual prepay is not misclassified as "one time revenue"

If you use GrowPanel reporting for subscription metrics, keep your MRR views focused on recurring activity (see MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue) and CMRR (Committed Monthly Recurring Revenue)) and treat one time payments as a separate analysis stream.

The Founder's perspective

Your goal isn't to drive one time payments to zero. Your goal is to stop them from polluting the signals you use to run the business: MRR growth, retention, and payback.

Benchmarks and practical targets

There's no universal "good" number. But there are useful ranges and red flags.

Typical ranges (rule-of-thumb)

| SaaS model | One time share of cash collected | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Self-serve SMB | 0% to 10% | Usually low; spikes often come from annual prepay misclassification or one-off promos. |

| Product-led with paid onboarding option | 5% to 15% | Often tied to higher tiers or specific segments. |

| Sales-led mid-market | 10% to 30% | Implementation and training are common; watch delivery margin. |

| Enterprise with heavy rollout | 15% to 40% | Can be healthy if margin is strong and delivery is standardized. |

Red flags founders should investigate

- One time share rising while MRR growth slows. You may be compensating for weak subscription momentum.

- Refunds rising with one time volume. Often expectation mismatch, fulfillment bottlenecks, or low-quality acquisition.

- One time payments concentrated in a few customers. That's customer concentration risk in a different form; see Customer Concentration Risk.

- One time payments tied to distressed behavior. Late fees, manual invoice re-issues, and "support charges" can indicate retention issues (check Logo Churn and churn reasons via Churn Reason Analysis).

When the metric breaks

One time payments are straightforward until your billing and data model aren't. Here are the most common failure modes.

Misclassifying annual subscriptions as one time

Because cash hits once, founders sometimes tag it as one time. That breaks:

- MRR/ARR trend lines

- retention calculations

- forward-looking planning

Fix: treat annual subscriptions as recurring revenue with different billing frequency. Use Deferred Revenue concepts to reconcile cash vs revenue.

Conflating "invoice issued" with "cash collected"

If you invoice for implementation but collect later, you don't have a payment yet—you have receivables. That's why Accounts Receivable (AR) Aging matters: it tells you if your one time "sales" are turning into cash on time.

Ignoring refunds, disputes, and tax

A spike in one time payments can be immediately reversed by:

- refunds (customer remorse, scope issues)

- chargebacks (fraud, unclear descriptor, weak receipts)

- tax handling errors (VAT included in "revenue")

Founders should review one time payments alongside refund rate and dispute rate, and ensure taxes are excluded from revenue views; see VAT handling for SaaS.

Classify based on economic intent: recurring obligation vs defined-scope non-recurring work vs upfront cash for recurring value.

Operational playbook

If you want one time payments to be useful (not noisy), implement these practices:

- Define categories and stick to them. Setup, implementation, training, one-off add-ons, ad hoc usage, hardware, and adjustments.

- Separate gross and net. Always review one time payments net of refunds and chargebacks.

- Track attach rate. Of new customers, what percent pay a setup/implementation fee? Pair this with win rate and sales cycle.

- Measure delivery margin for services. If implementation requires engineers, it can quietly crush gross margin; monitor COGS (Cost of Goods Sold) and Gross Margin.

- Use cohort views to validate value. Customers who paid one time should retain at least as well as those who didn't—otherwise you're charging for friction, not outcomes.

How to interpret changes month to month

When one time payments jump, ask these four questions in order:

- Is it classification drift? (annual prepay mis-tagged, taxes included, invoices vs payments)

- Is it mix? (more enterprise deals closing, different onboarding package)

- Is it price or packaging? (setup fee introduced or increased)

- Is it quality? (refunds/chargebacks rising, delivery backlog)

Then decide what to do:

- If the jump is healthy and profitable, you can invest in scalable delivery (templates, onboarding playbooks) and potentially raise prices.

- If it's masking weak MRR, refocus on subscription value and retention levers: product activation, expansion, and churn reduction (see Net Negative Churn and Expansion MRR).

- If it's driven by disputes, fix acquisition quality, receipts, and fulfillment; see Chargebacks in SaaS and Refunds in SaaS.

If you treat one time payments as a first-class metric—separate from MRR, net of refunds, and tied to clear categories—you get the best of both worlds: cleaner subscription analytics and a sharper view of the non-recurring cash levers in your business.

Frequently asked questions

Usually no. MRR and ARR are for recurring subscription revenue. One time payments are non-recurring charges like setup fees, implementation, one-off credits reversals, or add-ons that do not imply an ongoing billing obligation. Mixing them into MRR inflates growth and makes churn and retention metrics misleading.

It depends on your model. For a pure self-serve SaaS, one time payments are often small, commonly under 5 to 10 percent of cash collected. For sales-led SaaS with onboarding or implementation, 10 to 30 percent can be normal. The key is consistency and gross margin, not the absolute level.

Founders should track one time payments net of refunds and chargebacks so the number reflects durable cash. If your one time line spikes but refunds spike one to two weeks later, you have a fulfillment, expectation-setting, or fraud issue. Use a separate view for gross and for net to diagnose.

Annual prepayments are not one time payments from a revenue perspective even though cash arrives once. They are recurring subscription revenue collected upfront and usually map to deferred revenue and then recognized revenue over time. Setup fees may be one time, but only if they are not required every renewal.

They reveal whether customers will pay extra for outcomes outside the core subscription. If one time revenue scales with expansion or seat growth, it may belong as an add-on or usage-based component. If it is mostly discount reversals or support charges, it signals packaging confusion and weak expectations.