Table of contents

Lead-to-customer rate

If you're spending money to create leads, lead-to-customer rate is the metric that tells you whether that spend is turning into real revenue—or just more activity for your team.

Lead-to-customer rate is the percentage of leads you generate that become new paying customers in a defined time window. It's a blunt metric on purpose: it forces you to connect top-of-funnel volume to bottom-of-funnel outcomes.

What it reveals

Founders use lead-to-customer rate to answer one core question: are we turning demand into customers efficiently? It's the conversion "bridge" between marketing generation and sales execution.

What it tends to reveal quickly:

- Lead quality vs. lead volume tradeoffs. You can buy more leads and still grow slower if quality drops.

- Sales capacity constraints. When the rate falls after hiring freezes, rep churn, or higher inbound volume, you're seeing follow-up and throughput limits.

- Funnel friction that doesn't show in pipeline. A "healthy pipeline" can coexist with poor lead-to-customer conversion if deals stall, disqualify late, or lose to pricing and procurement.

- A hidden CAC problem. If your CPL (Cost Per Lead) is stable but lead-to-customer rate falls, your CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost) is quietly rising.

The Founder's perspective

If I can't explain what changed in lead-to-customer rate this month, I don't really know why growth is happening—or why it's slowing.

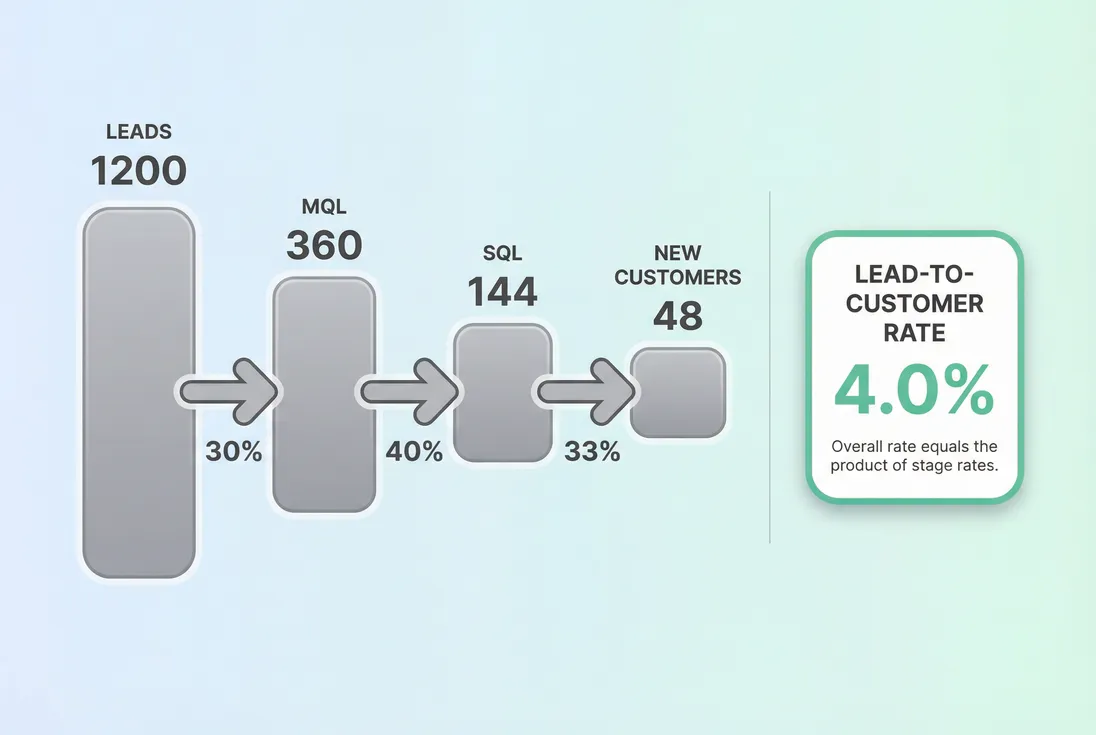

A simple funnel decomposition shows lead-to-customer rate as the outcome of multiple stage conversions, making it easier to diagnose what actually changed.

How to calculate it

The core calculation is straightforward:

The decisions (and confusion) come from defining new paying customers, defining leads, and choosing the time window.

Define the numerator precisely

For most SaaS teams, "new paying customers" should mean:

- First-time paid subscription started (not reactivations)

- Exclude expansions and upgrades (those belong in retention and expansion metrics)

- Count unique accounts, not invoices

If you're mixing reactivations into the numerator, your lead-to-customer rate can look "better" while acquisition is actually flat. Keep reactivations separate and track them with retention metrics like Logo Churn and NRR (Net Revenue Retention).

Define what a lead is

Lead definitions vary by go-to-market:

- PLG/self-serve: signups, free trials, or activated accounts

- Sales-led inbound: demo requests, contact forms, webinar attendees (sometimes)

- Outbound: contacted prospects who engaged, booked, or met qualification criteria

The key is consistency. If your definition changes (for example, you start counting webinar attendees as "leads"), your rate can drop even if sales performance didn't change.

If you need adjacent metrics, lead-to-customer rate is not the same as:

- Conversion Rate (generic conversion concept across any step)

- Lead Conversion Rate (often used for lead-to-MQL or lead-to-SQL in marketing analytics)

- Win Rate (typically SQL-to-close, opportunity-to-close)

Choose the time window (this is where teams go wrong)

The biggest measurement trap: dividing customers closed this month by leads created this month. That only works when sales cycles are extremely short and stable.

Most SaaS teams should track two views:

- Cohort view (recommended for diagnostics): leads created in a period, and the percent that become customers within 30/60/90 days. This naturally accounts for Sales Cycle Length changes.

- Calendar view (useful for forecasting): customers closed in a period divided by leads created in a prior period (often lagged by your median cycle time).

The Founder's perspective

If sales cycles lengthen, a calendar-month lead-to-customer rate can "collapse" even when the underlying funnel hasn't changed. Cohorting keeps you from making the wrong budget cut.

What moves the rate

Lead-to-customer rate is an output metric. To improve it reliably, you need to understand the input levers.

Lever 1: Channel mix and targeting

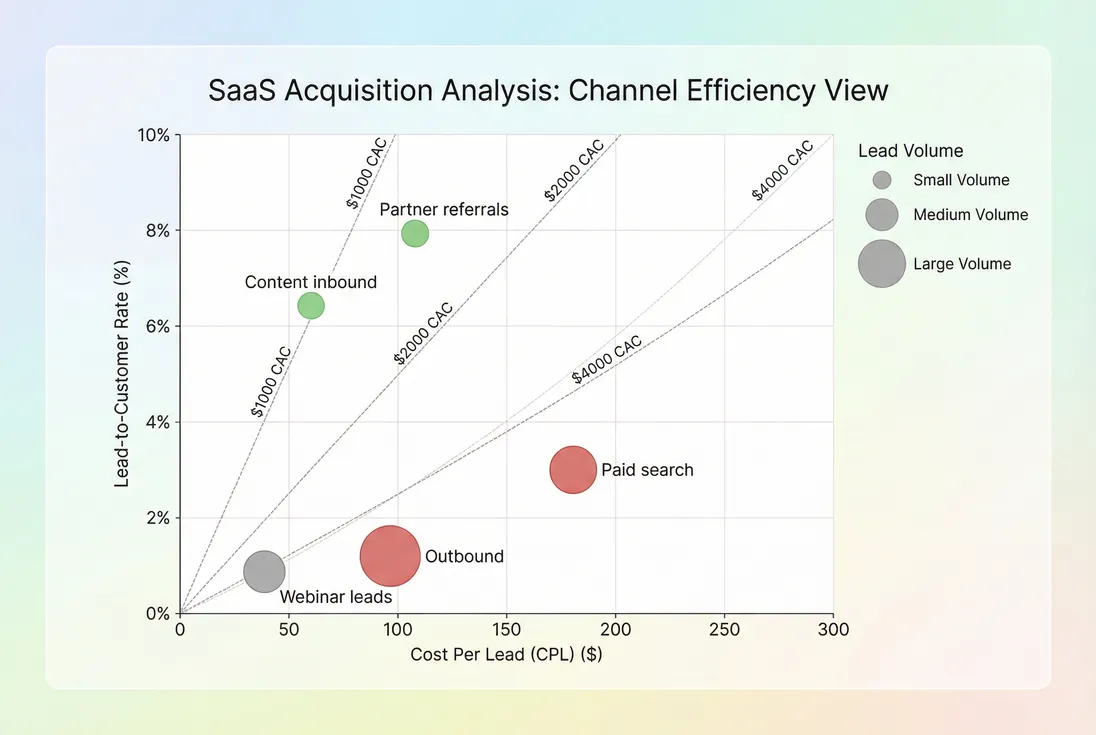

Your blended rate is usually a weighted average of channels with very different performance. A common pattern:

- You add a new paid channel with lower CPL (Cost Per Lead)

- Lead volume jumps

- Lead-to-customer rate drops because the new channel converts worse

- CAC rises (even though CPL "improved")

That's not inherently bad. If the new channel unlocks scale and still produces acceptable CAC relative to LTV (Customer Lifetime Value), it may be the right trade. But you need segmentation to see it.

Lever 2: Lead qualification quality

If you qualify too loosely, you inflate SQLs and pipeline but don't create customers. If you qualify too tightly, you starve sales of opportunities and slow learning.

Watch for:

- High meeting set rate but low progression to close

- Lots of late-stage disqualifications (wrong segment, missing integration, security requirements)

- Frequent discounting to force deals through (see Discounts in SaaS)

Lever 3: Speed to lead and follow-up consistency

For inbound leads, response time is often a top driver. When speed-to-lead gets worse (vacations, hiring gaps, "busy weeks"), conversion falls in ways that look mysterious if you only stare at the rate.

Operational fixes that often matter more than new messaging:

- Enforce first-touch SLAs

- Use lightweight qualification before booking

- Reduce handoffs between SDR and AE for smaller deals

Lever 4: Offer, pricing, and perceived risk

Changes that can move the rate fast:

- Trial length, onboarding path, activation (especially PLG)

- Pricing packaging and plan boundaries (see ASP (Average Selling Price) and Per-Seat Pricing)

- Security/compliance readiness for larger deals (SOC 2, SSO)

- Contract terms and billing friction

If you raise prices and the rate drops, that's not automatically failure. The right question is whether CAC payback and gross margin economics improved. Tie changes back to CAC Payback Period and revenue quality.

Lever 5: Product onboarding and time to value

For trial-based and product-led funnels, lead-to-customer rate is often more about onboarding than "sales."

If your activation step is unclear, or time-to-value is long, you'll see:

- Many leads "look interested" but never convert

- Heavier reliance on discounts to close

- Higher early churn, even when acquisition looks fine (connect to Customer Churn Rate)

How to interpret changes

A lead-to-customer rate change is only useful if you can explain it. Here's a practical interpretation framework.

First, quantify impact in dollars

Lead-to-customer rate has a direct relationship to CAC when you use CPL as the input cost.

If you define lead-to-customer rate as a fraction (not a percent), then:

Example:

- CPL = 120 dollars

- Lead-to-customer rate = 0.04 (4 percent)

CAC from lead cost alone ≈ 3,000 dollars.

If you improve the rate from 4% to 5% (0.04 to 0.05), CAC from lead cost drops to 2,400 dollars—a 20% improvement—often without spending a dollar more on ads.

The Founder's perspective

A one-point improvement in conversion is not a vanity win. It can be the difference between sustainable growth and a CAC spiral.

Then, segment before you speculate

Never debug the blended metric first. Segment by:

- Channel (paid search, outbound, partners, content)

- Persona or industry

- Company size (SMB vs mid-market)

- Geo (if your product is region-sensitive)

- Product tier or use case

If you can't segment, you'll end up making broad changes (budget cuts, pricing reversals, rep performance plans) that are directionally wrong.

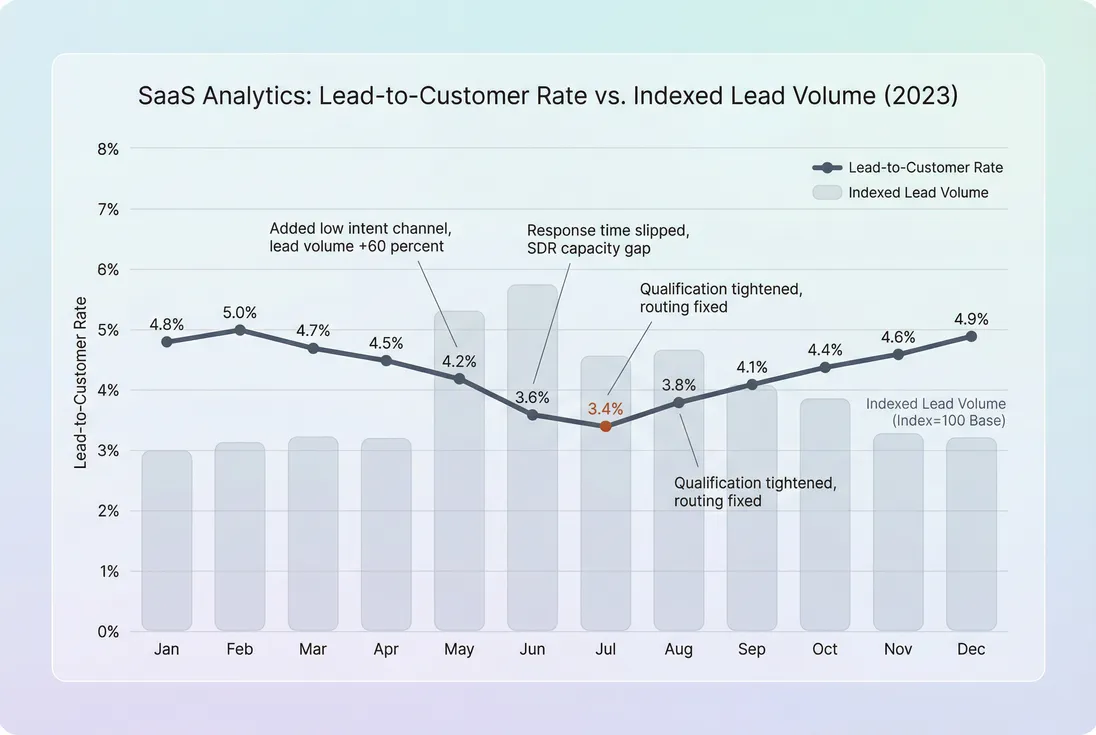

A trend line becomes actionable when you annotate it with real funnel events like channel mix shifts, capacity gaps, and qualification changes.

Watch for "false" improvements

Lead-to-customer rate can improve for reasons that don't actually make the business healthier:

- You reduced lead volume by cutting upper-funnel spend, keeping only the highest-intent leads. Rate rises, but growth may slow and CAC may worsen long-term.

- You reclassified leads (narrower definition). Rate rises, but you didn't improve conversion.

- You pushed discounts to close deals. Rate rises, but ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account) and payback may degrade.

A good habit: when the rate rises, confirm that downstream metrics didn't deteriorate:

- CAC and payback (see CAC Payback Period)

- Revenue quality, including ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue) growth

- Retention (see GRR (Gross Revenue Retention) and NRR (Net Revenue Retention))

Benchmarks founders can actually use

Benchmarks are only helpful when tied to your lead definition and motion. Use these as rough orientation, not targets.

| Motion and lead definition | Typical lead-to-customer rate | What "good" usually means |

|---|---|---|

| PLG signup or free trial → paid | 1% to 6% | Strong onboarding, clear activation, value visible fast |

| Inbound demo request → customer | 5% to 20% | Tight ICP targeting, strong discovery, solid follow-up |

| Outbound sourced lead → customer | 0.5% to 3% | Great list quality, compelling offer, disciplined sequences |

| Enterprise with long procurement | 0.2% to 1.5% | High ACV, high win quality, strong multi-threading |

If you want a more apples-to-apples benchmark, compare within your own history after controlling for:

- channel mix

- sales cycle length

- qualification definition changes

When it breaks (common failure modes)

Misaligned timing windows

If you're measuring leads created this month against customers closed this month, a longer sales cycle will make conversion look worse—especially after you move upmarket.

Fix: measure lead cohorts and include lagged conversion windows (30/60/90 days).

Duplicate or low-intent leads inflate the denominator

Duplicate CRM entries, spam, students, job seekers, competitors—these all crush the rate without reflecting true market demand.

Fix: implement lead hygiene rules:

- dedupe by email and domain

- block obvious non-buyers

- separate "inquiries" from "qualified leads"

Handoff problems between marketing and sales

If marketing optimizes to MQL volume but sales optimizes to SQL quality, lead-to-customer rate becomes the battleground metric.

Fix: define a shared qualification contract and review drop-off reasons weekly:

- wrong segment

- no budget

- missing feature

- timing

- competitor

If you're building real pipeline discipline, connect this to Qualified Pipeline and stage exit criteria.

How founders use it to make decisions

Decision 1: Scale spend or fix conversion

A practical rule: if lead-to-customer rate drops when you scale spend, don't immediately cut spend. First ask:

- Did channel mix change?

- Did speed-to-lead degrade?

- Did sales capacity keep up?

- Did lead quality shift away from ICP?

If the rate drops mostly in one channel, you don't have a "marketing problem," you have a channel problem.

Decision 2: Hire SDRs or improve routing

If lead volume rises and the rate falls, that's often a throughput issue, not a persuasion issue.

Leading indicators of capacity constraints:

- first response time increasing

- leads aging without touch

- more no-shows and reschedules

- fewer touches per lead

In those cases, hiring (or fixing routing and SLAs) can raise conversion faster than rewriting the website.

Decision 3: Change pricing without guessing

Pricing changes often move lead-to-customer rate immediately, but the right evaluation is economic:

- If rate falls 15% but ASP rises 30%, that can still be a win (see ASP (Average Selling Price)).

- Then confirm payback and retention didn't worsen.

Lead-to-customer rate is your early warning signal; unit economics confirm whether the change was smart.

Decision 4: Choose your next growth lever

Once you've segmented, you can choose a lever based on what's actually broken:

- Good rate, low lead volume: invest in demand gen, partnerships, content, outbound list building.

- Low rate, good lead volume: fix qualification, follow-up speed, messaging, onboarding, or pricing.

- High rate in one segment: double down there and tighten ICP focus.

Plotting cost per lead against lead-to-customer rate quickly reveals which channels are efficient, which are scalable, and which are quietly inflating CAC.

A simple operating cadence

If you want this metric to drive real outcomes, put it into a lightweight weekly or biweekly review:

- Review overall rate and trend (cohort-based, not just calendar month).

- Segment by channel and ICP tier and identify the biggest movers.

- Pick one bottleneck to investigate (speed-to-lead, stage drop-off, late disqualifications, onboarding).

- Decide one action (routing fix, qualification change, channel budget shift, onboarding experiment).

- Re-measure in the next cohort window (30/60/90 days depending on your cycle).

This keeps lead-to-customer rate from becoming a "dashboard number" and turns it into a management tool.

Practical takeaway

Lead-to-customer rate matters because it ties your demand generation to revenue reality. Track it with a consistent lead definition, measure it in cohorts to avoid timing traps, and segment it aggressively. When it moves, it's usually telling you something specific about channel mix, qualification, capacity, or onboarding—and it's often the fastest path to lowering CAC without cutting growth.

Frequently asked questions

A good rate depends on your motion. Self-serve and product-led funnels often land in the low single digits because the lead definition is broad. Demo-led SMB might be 5 to 15 percent. Enterprise outbound can be below 2 percent but still great if ACV and retention are high.

Usually it is mix and qualification. New channels often bring cheaper but less qualified leads, which inflate the denominator. If sales capacity, follow-up speed, or targeting does not scale with volume, conversion falls. Segment the rate by channel, ICP fit, and response time before changing spend.

For diagnosing funnel health, prefer a cohort view: leads created in a period and whether they become customers within a defined window, like 30, 60, or 90 days. Close-won month views are useful for forecasting, but they hide the impact of lead quality and sales cycle length.

Lead to customer rate is the bridge between CPL and CAC. If you pay 100 dollars per lead and convert 5 percent, you are effectively paying about 2,000 dollars per customer before sales costs. Improving conversion is often the fastest way to reduce CAC without cutting spend.

Treating it as a single number. Blended lead to customer rate hides channel mix, persona differences, and capacity constraints. A flat overall rate can mask improvement in one segment and collapse in another. Always review it by channel, ICP tier, and sales stage progression.