Table of contents

Dilution in SaaS

Founders don't fail because they "gave up too much equity." They fail because they run out of time and cash before finding repeatable growth. Dilution is the lever that trades ownership for time, talent, and distribution—so you can reach the milestones that make the company meaningfully more valuable.

Dilution in SaaS is the reduction in an existing shareholder's ownership percentage when new shares are created (fundraising, option pools, conversions, or equity grants). Your number of shares might stay the same, but the total share count increases—so your slice of the pie shrinks.

What dilution actually measures

Dilution is easiest to understand as "percentage ownership after a change in the cap table."

- You own shares (founder common).

- The company creates new shares (preferred shares for investors, options for employees, conversion shares for SAFEs/notes).

- The total shares increase, so your ownership percentage decreases.

Two important clarifications:

- Dilution is not automatically bad. If the round materially increases the company's value, your smaller percentage can still be worth more.

- Dilution is not one thing. In SaaS, it usually comes from four sources:

- Priced equity rounds (seed, Series A, etc.)

- Option pool creation or expansion

- SAFEs/convertible notes converting into equity

- Employee grants and refreshes over time

The Founder's perspective

The question is rarely "How do I avoid dilution?" It's "What is the minimum dilution required to hit the next value inflection point—product-market fit, repeatable acquisition, retention proof, or efficient scaling?"

How to calculate dilution (without getting tricked)

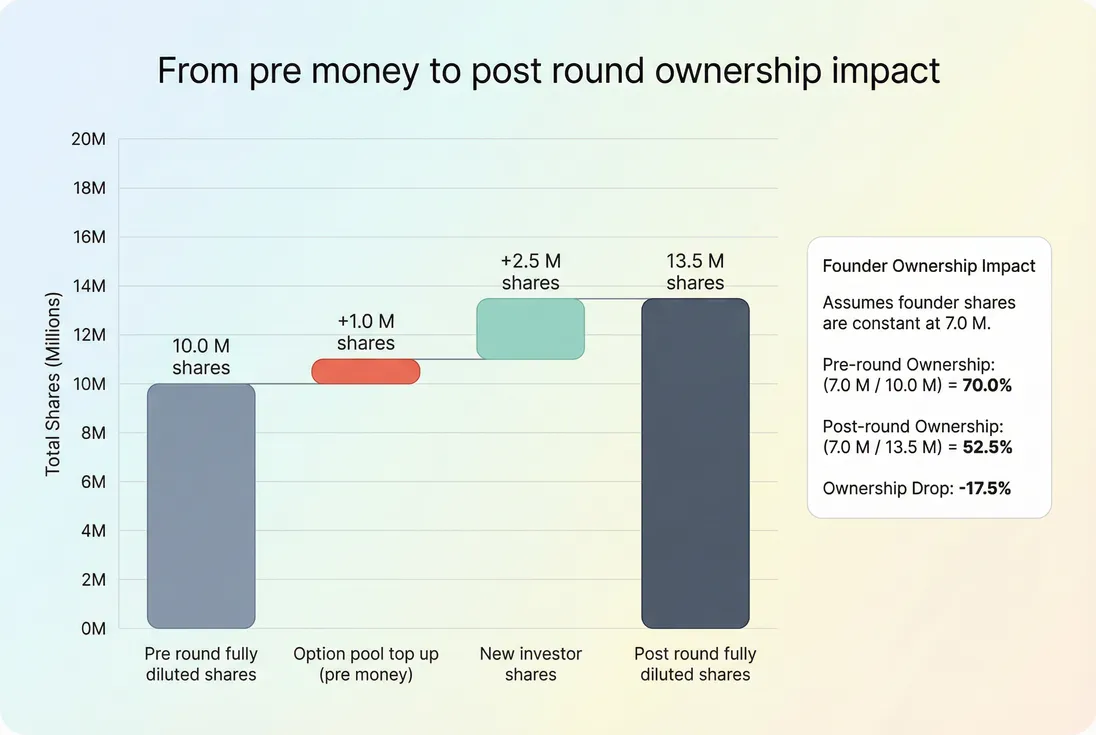

At the simplest level, dilution is driven by how many new shares are created relative to the existing fully diluted shares.

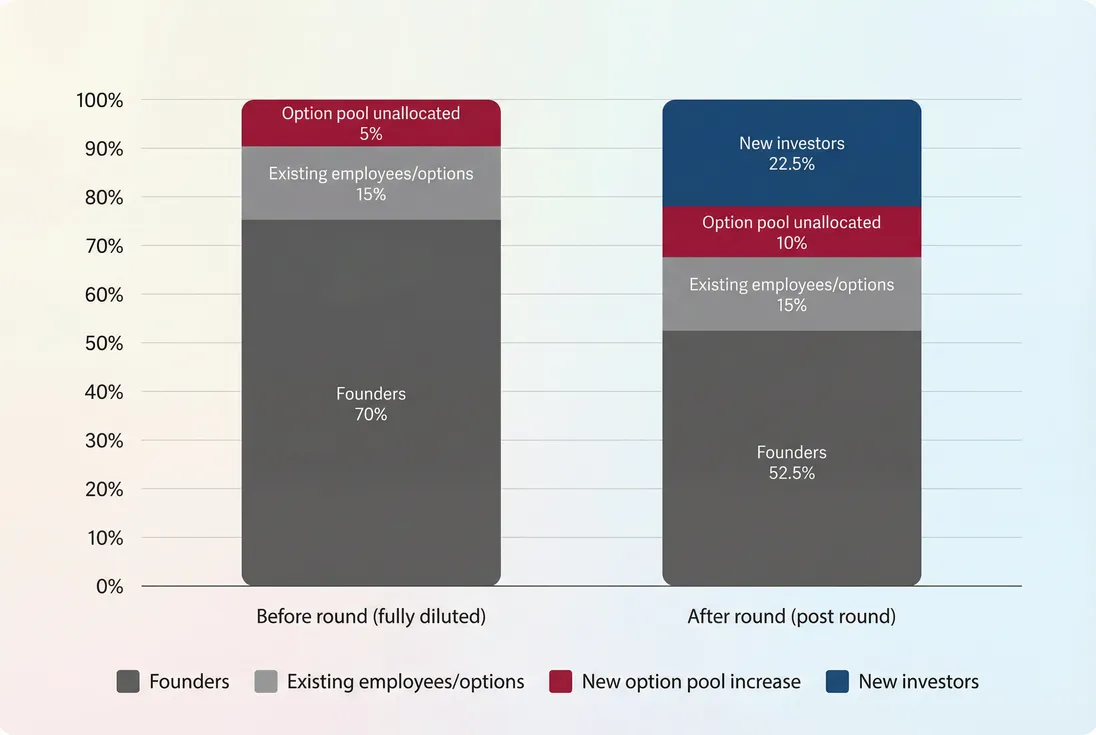

Ownership changes are usually driven by both the investor check and the option pool increase; founders often underestimate the pool's impact because it is "non-cash" dilution.

Core formulas

Post-money valuation is the pre-money valuation plus the new capital:

If you model dilution using shares, an existing holder's ownership after new shares are issued is:

So the dilution percent to existing holders from that issuance is:

A concrete SaaS example

Assume a seed round:

- Founders currently own 70%

- Existing employee/options represent 20% (granted + pool)

- You raise $3M at a $12M pre-money

- Investors therefore buy $3M / $15M = 20% post-money if nothing else changes

But "nothing else changes" is the trap. Many rounds include an option pool top-up to ensure hiring capacity. If the pool increases by, say, 5% of the company and it is negotiated pre-money, that 5% comes out of the existing holders (mostly founders).

That's why founders should always ask:

- Is the option pool expansion pre-money or post-money?

- What does the cap table look like on a fully diluted basis?

Multi-round dilution compounds

If you dilute 20% in one round, then 20% again later, you did not dilute 40%—you diluted 36% cumulatively.

(Practically: 100% → 80% → 64%.)

What drives dilution in SaaS rounds

Dilution is a negotiated output of a few inputs. If you want to manage dilution, you manage these inputs.

1) Round size (how much you raise)

More money usually means more dilution, but the relationship isn't linear if a larger round also increases valuation by reducing risk.

A useful way to frame "how much is enough" is to tie the raise to runway and milestones, not a vague growth plan. Start with Burn Rate and Runway:

- How many months of runway do you have today?

- How many months do you need to reach the next milestone that improves valuation leverage?

- What buffer do you need for uncertainty (sales cycles, churn surprises, hiring delays)?

The Founder's perspective

If you can't describe the milestone that the money buys, you're buying optionality at founder-equity prices. Optionality is expensive.

2) Valuation (price of dilution)

Higher valuation means less dilution for the same dollars raised. In SaaS, valuation is usually justified by measurable traction, such as:

- ARR scale and growth rate (ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue))

- Retention strength (NRR (Net Revenue Retention) and GRR (Gross Revenue Retention))

- Efficient growth (Burn Multiple)

- Sales efficiency signals like CAC Payback Period and LTV (Customer Lifetime Value)

Valuation is not just a pitch-deck number—it's a reflection of how much risk remains.

3) Option pool size and timing

Option pools dilute everyone, but founders feel it most early. The key is not "avoid an option pool" (you need one), but set it with a hiring plan.

Common pool dynamics in SaaS:

- Early seed: pool often 10–20% fully diluted (varies widely)

- After a hiring ramp: you may need a refresh before Series A

- The earlier you add it, the more it hits founders (because founders are the majority owners)

A good practice: build a 12–18 month hiring plan and estimate equity needs by role seniority and market norms, then size the pool accordingly. Oversizing the pool "just in case" is silent dilution.

4) SAFEs and convertible notes ("shadow dilution")

SAFEs/notes defer the pricing decision. That can be great for speed, but it hides the true ownership outcome until conversion.

What increases dilution at conversion:

- Low valuation caps (more shares issued)

- High discounts

- Multiple SAFE rounds stacked on top of each other

- MFN clauses that upgrade earlier investors into better terms

If you use SAFEs, model at least three outcomes: base, conservative, worst-case cap scenario. Treat the worst case as real until it isn't.

5) Secondary sales (who gets diluted vs who sells)

Secondary isn't dilution in the strict sense if it's existing shares sold to new buyers (no new shares created). But it affects founder economics and incentives:

- It can reduce personal risk and improve decision-making

- It can also be viewed negatively if it's large relative to the round and traction

Be explicit about why you want it and how it aligns with building value.

What dilution reveals about your business

Dilution is not an operating metric like MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue). It's a strategy metric that reveals whether your company needs outside capital to win—and what that capital will cost you.

Dilution is a proxy for risk

High dilution typically signals one (or more) of these realities:

- The business is still high-risk (uncertain retention, unclear distribution, inconsistent pipeline)

- The round is oversized relative to traction

- The company has weak leverage (few investor options, unclear narrative, messy metrics)

- There is hidden dilution (SAFE stack, big pool top-up, unusual preferences)

Low dilution usually indicates:

- Strong investor demand (often driven by clean retention and efficient growth)

- A smaller, milestone-based raise

- A founder-friendly structure (reasonable pool, simpler conversion terms)

Dilution connects directly to capital efficiency

If you're raising to "buy growth," you should be able to articulate how efficiently the capital turns into ARR and retention improvement.

Two practical checks founders use:

- Burn Multiple sanity check: If your burn multiple is high, more capital may just fund inefficiency. Use Burn Multiple to pressure-test the plan.

- Retention reality check: If churn or contraction is the core issue, fundraising won't fix it. Look at Net MRR Churn Rate and MRR Churn Rate before you assume scale will solve it.

The Founder's perspective

If retention is weak, dilution buys time—but it also locks you into a clock. Investors expect the next round to be up and to the right. Fix retention early; it improves valuation and reduces future dilution.

When dilution is worth it (and when it isn't)

The right way to judge dilution is by comparing:

- Ownership you give up

- Probability-weighted value you gain

You can't calculate probability perfectly, but you can make the decision far less emotional.

A decision table founders actually use

| Situation | Dilution is usually worth it when… | Be careful when… |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-PMF seed | Capital funds learning cycles, not headcount bloat | You raise big before retention signals exist |

| Scaling PLG | Capital accelerates activation and expansion with proven cohorts | You rely on discounting to force growth (Discounts in SaaS) |

| Scaling sales-led | Capital funds reps after you've proven payback | CAC payback is long and pipeline quality is unclear |

| Enterprise move-upmarket | Capital funds product, security, and longer sales cycles | You underestimate time-to-close and services burden (COGS (Cost of Goods Sold)) |

A simple "value-per-dilution" check

Ask: "If I accept 20% dilution, what must be true in 18 months for that to be a great trade?"

Examples of crisp answers:

- "We reach $2M ARR with NRR above 115% and a repeatable outbound motion."

- "We cut churn in half and prove expansion MRR covers churn."

- "We reach a burn multiple under 1.5 while doubling ARR."

If you can't state the target clearly, your round size is probably driven by anxiety, not a plan.

How to manage dilution over time

Managing dilution is mostly about staying fundable on your terms.

A share-based waterfall makes "invisible" dilution (like option pool increases) explicit, so founders can negotiate structure, not just valuation.

1) Raise to milestones, not maximums

In SaaS, the most dilution-efficient path is often two smaller raises tied to clear derisking milestones rather than one oversized round that funds uncertainty.

To do this well, your internal reporting needs to be tight on:

- Revenue scale and movement (MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue))

- Expansion vs churn (Expansion MRR, Contraction MRR)

- Cohort retention evidence (Cohort Analysis)

2) Control the option pool narrative

Investors will ask for a pool that supports hiring. You should arrive with:

- A role-by-role hiring plan

- Estimated equity ranges by role level

- A clear statement of what you already have granted vs reserved

Negotiation isn't only about pool size; it's also about timing:

- If the pool increase is post-money, dilution is shared with the new investor.

- If it's pre-money, it largely hits existing holders.

3) Avoid "SAFE stacking" without modeling

Multiple SAFE rounds can quietly turn into a major dilution event at Series A. If you must stack SAFEs:

- Track each instrument's cap, discount, and any special rights

- Build a conversion model and revisit it every time you add new paper

- Consider whether a priced round is actually simpler and less dilutive given momentum

4) Don't let discounting create fake valuation pressure

Founders sometimes accept higher dilution because the company's metrics are weaker than they appear—often due to aggressive discounting or non-standard billing.

If pricing is messy, clean it up before fundraising:

- Ensure discount policies are consistent (Discounts in SaaS)

- Watch for ARPA compression (ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account))

- Be clear about what is recurring vs one-time (One Time Payments)

5) Know what dilution does to incentives

A cap table can become a motivation problem long before it becomes a control problem. If founders and early employees are diluted heavily without clear upside, you'll feel it in:

- Hiring difficulty

- Retention of key leaders

- Risk tolerance (people optimize for safety, not outcomes)

This is why many great SaaS teams treat equity like a product: planned, communicated, and refreshed deliberately.

The Founder's perspective

The "best" ownership percentage is the one that keeps the founding team hungry, the executives aligned, and the company sufficiently funded to win its market. Too little ownership can kill urgency; too little capital can kill the company.

Practical benchmarks and red flags

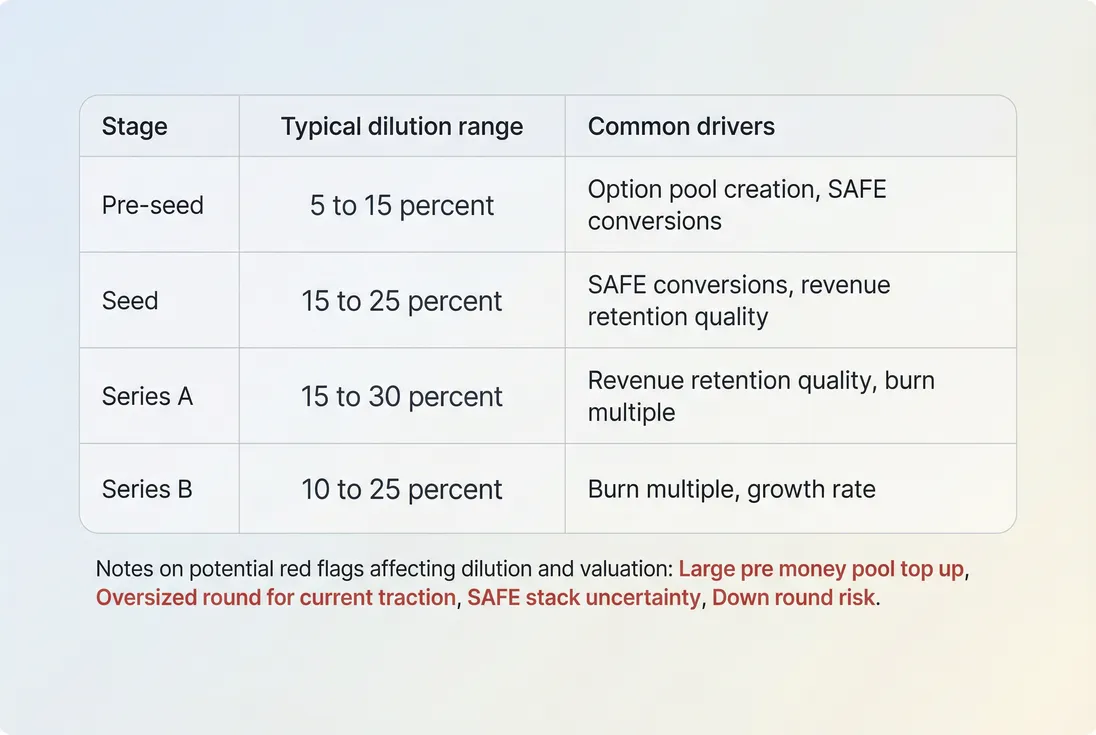

Benchmarks vary by market and leverage, but founders benefit from ranges as a starting point (not a rule).

Use dilution ranges as a negotiation starting point; the real goal is aligning round size, valuation, and option pool needs with your next derisking milestone.

Red flags that usually lead to unnecessary dilution

- Raising before retention is understood. If you can't explain churn drivers, fix that first using Churn Reason Analysis.

- Optimizing for headline valuation while ignoring structure. A "higher valuation" with a large pre-money pool or heavy SAFE conversion can be worse than a slightly lower valuation with clean terms.

- Funding inefficiency. If burn multiple is persistently high, more capital can amplify the wrong motion.

- Messy revenue quality. Refunds, chargebacks, or billing edge cases can spook investors and reduce leverage—see Refunds in SaaS and Chargebacks in SaaS.

How founders should talk about dilution internally

Dilution is emotional. Treat it like an operating constraint:

- Set a target ownership band for founders and key executives post-next-round.

- Decide upfront how much dilution you're willing to accept to hit a specific milestone.

- Communicate equity strategy to leadership so compensation, hiring, and fundraising don't conflict.

A simple internal cadence that works:

- Quarterly cap table model refresh (including SAFEs/notes and pool needs)

- Quarterly review of metrics that influence valuation and leverage: ARR growth, retention, burn multiple, payback

- Revisit fundraising plan only when the next milestone plan changes

Related metrics and concepts

If you're using dilution to make fundraising decisions, these are the operational inputs that usually matter most:

- Burn Rate and Runway

- Burn Multiple

- ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue) and MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue)

- NRR (Net Revenue Retention) and GRR (Gross Revenue Retention)

- CAC Payback Period and LTV (Customer Lifetime Value)

Dilution is the cost side of the "raise vs bootstrap" decision. Your job is to make sure you're paying that cost only when it increases your odds of building a much larger, much more durable SaaS business.

Frequently asked questions

Many SaaS seed rounds land around 15 to 25 percent dilution, with Series A often another 15 to 30 percent. The exact number depends on valuation, round size, and option pool increases. The key is whether the capital meaningfully improves growth and reduces risk versus the ownership you give up.

Because investors price deals on a fully diluted basis, meaning they assume all reserved options exist today. If the option pool is increased pre money, the new shares typically come out of the founders and existing holders before the investor buys in. That shift reduces founder ownership immediately on paper.

Dilution is an ownership percentage change. Control is about voting power, board seats, protective provisions, and who can approve major decisions. You can be diluted and still control the company, especially early. But repeated rounds, new board structures, and investor rights can reduce control faster than percentage alone suggests.

SAFEs and notes create shadow dilution: you will not see the exact ownership impact until conversion terms are finalized at a priced round. Valuation caps, discounts, and most favored nation clauses can materially increase the number of shares issued at conversion. Model multiple conversion outcomes before committing to more paper.

Dilution is usually worth it when the capital increases enterprise value faster than it reduces your ownership. Practically, that means it extends runway, accelerates ARR growth, improves retention, or opens a credible path to product distribution that you could not fund organically. If outcomes are uncertain, stage the raise or reduce burn.