Table of contents

Customer lifecycle duration

Founders feel "duration" as cash confidence. If customers stick around longer, you can spend more to acquire them, invest in onboarding, and still hit payback targets. If they leave faster, you're forced into constant reacquisition and your growth becomes fragile—even if new bookings look strong.

Customer lifecycle duration is the amount of time a customer remains active in a defined lifecycle window—most commonly from first paid date to churn date—reported as an average (mean) or typical value (median) across customers.

What customer lifecycle duration reveals

Lifecycle duration answers one operational question: how long you get paid after you win a customer. That cascades into four core decisions:

- LTV realism. Duration is a multiplier inside LTV (Customer Lifetime Value). If duration is overstated, you'll overpay for acquisition and think you have product-market fit earlier than you do.

- Churn urgency. Two companies with the same Customer Churn Rate can have very different "shape" of churn—one leaks early, the other leaks late. Duration helps you locate the leak.

- Go-to-market fit. If duration is short in one segment (say, agencies) but long in another (say, in-house teams), that's a targeting and packaging signal.

- Cash planning. Short duration forces short CAC Payback Period targets. Longer duration can support slower payback—if you have the balance sheet to wait.

The Founder's perspective: If lifecycle duration is shrinking, I treat every growth plan as riskier. Hiring ahead of revenue, increasing paid acquisition, and expanding sales headcount all become harder to justify until retention stabilizes.

Where lifecycle duration starts and ends

Most teams get misleading numbers because they don't align definitions with decisions. Pick the definition that matches the question you're answering.

The default (best for revenue decisions)

Start: first paid invoice date (or subscription start date)

End: churn effective date (when access ends or subscription stops renewing)

This aligns cleanly with revenue metrics like MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue) and Logo Churn. It also avoids mixing retention with funnel speed.

Alternatives (useful, but keep separate)

- Signup-to-churn: good for diagnosing onboarding and activation, but punishes you for longer onboarding or sales cycles.

- Activation-to-churn: good for product analytics, but requires a stable activation definition.

- Contract start-to-non-renewal: best for annual enterprise where churn happens at renewal boundaries.

Mean vs median (pick intentionally)

- Mean duration (average): moves a lot with a few very long-lived customers. Useful for modeling total revenue, but easy to distort.

- Median duration (typical): "half of customers churn before X." Often better for founders because it's harder to game and more stable across time.

In practice, report both. The gap between mean and median is a signal about whether you rely on a small set of "lifers."

How to calculate it reliably

There are three common ways to calculate lifecycle duration. Each is "correct" in a different context—founders get in trouble when they use the easy one for the wrong job.

Method 1: simple average of churned customers (fast, biased)

For each churned customer, compute months active, then average.

This is easy—and usually wrong early on—because it ignores active customers (who, by definition, have longer durations). The more you're growing, the more downward-biased this becomes.

Use it when:

- You have a mature, stable business with consistent churn behavior.

- You're segmenting tightly (same plan, same contract type, same acquisition motion).

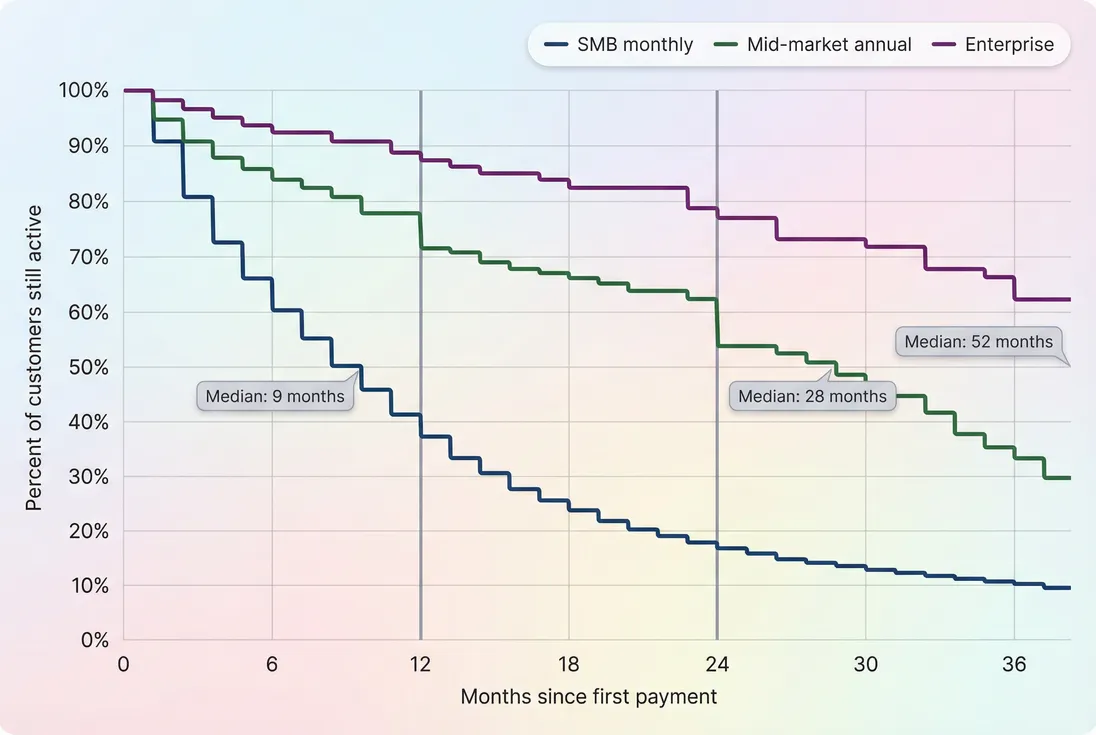

Method 2: cohort survival (best for truth)

Track a cohort of customers by start month and measure what percent remain active over time. The "duration" becomes something like:

- Median duration: the month when survival drops below 50%.

- Percent surviving at 12/24 months: for renewal and planning.

This is where Cohort Analysis and retention curves do the heavy lifting: you're not forced to pretend active customers have a final churn date.

Use cohort survival when:

- You're still growing fast (most customers are "too new to churn").

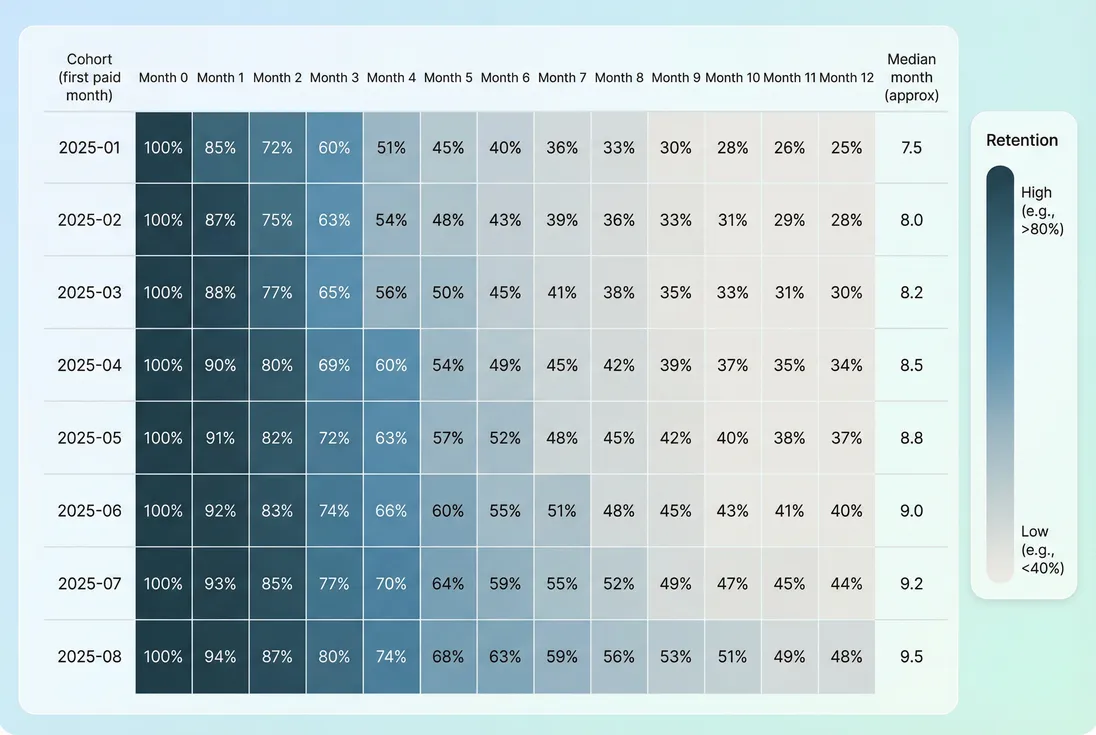

- You changed onboarding, pricing, packaging, or ICP and need clean before/after comparisons.

- You sell annual contracts and churn clusters at renewals.

Method 3: churn-rate inversion (useful approximation)

If churn is relatively stable for a segment, you can approximate expected duration from monthly logo churn:

Example: if monthly logo churn is 4%, expected duration is ~25 months.

Cautions:

- This assumes a steady churn process, which is often false (many SaaS products have heavy early churn).

- It's sensitive to how you define churn timing (see when you should recognize churn in SaaS).

Practical setup: what to segment by first

Lifecycle duration is rarely a single company-wide truth. Segment it before you act on it:

- Contract term: monthly vs annual vs multi-year (see Average Contract Length (ACL)).

- Plan / price point: duration often increases with higher ASP (Average Selling Price) because the customer is more committed and success is more managed.

- Acquisition motion: self-serve vs sales-led.

- Use case / industry: especially if switching costs differ.

- Payment behavior: separate involuntary churn (failed payments) from true cancellations (see Involuntary Churn).

If you're using GrowPanel, this is where cohorts, retention, filters, and the customer list become practical: you want duration by slice, not a blended average that hides the problem segment.

How to interpret changes

A shift in lifecycle duration is never "just a metric move." It's a statement about customer experience, fit, and commitment. The key is to determine whether the change is real, and then locate the mechanism.

If duration increases

Common real reasons:

- Better onboarding and faster time-to-value (see Time to Value (TTV)).

- Reduced involuntary churn (card updater, dunning).

- Stronger expansion and stickiness (often shows up alongside stronger NRR (Net Revenue Retention) even if logos are flat).

- Moving upmarket (higher switching costs, longer buying cycles, longer stays).

Common "optical" reasons:

- You switched more customers to annual prepay, delaying churn recognition.

- You changed churn recognition rules (cancel vs end-of-term).

- You have fewer mature cohorts (business is newer), so you're extrapolating from limited history.

What to do:

- Look at 12-month survival for cohorts before/after the change.

- Separate voluntary vs involuntary churn to understand whether product value improved or billing ops improved.

If duration decreases

Common real reasons:

- ICP drift: you're winning customers who were never a great fit.

- Feature gap emerges (competitors, platform changes, reliability issues).

- Pricing/packaging mismatch: customers realize they overbought or can't justify renewals (see Price Elasticity and Discounts in SaaS).

- Onboarding got slower (new complexity, too many required steps).

Common "optical" reasons:

- You launched a cheaper entry plan that attracts higher-churn users.

- You increased top-of-funnel volume with lower-intent sources.

- Refund policy changes (see Refunds in SaaS) shift how cancellations are recorded.

What to do:

- Compare lifecycle duration by first invoice amount or initial plan. A sudden drop in the "entry" segment with stable mid-tier often means acquisition quality, not product regression.

- Run churn reason analysis (see Churn Reason Analysis) and tie reasons to lifecycle timing (early vs late).

The "shape" matters more than the average

Two patterns create the same average duration but require different fixes:

- Early churn spike (months 0–2): onboarding, activation, expectations, targeting.

- Late churn at renewals (month 12/24): ROI proof, champion change, procurement, competitive displacement.

Treat duration like a map of where customers fall off—not just a single number.

The Founder's perspective: I don't ask my team to "increase lifetime." I ask them to eliminate a specific churn shape: fix month-1 churn for self-serve, or fix renewal churn for annual contracts. Duration goes up as a result.

How founders use it

Lifecycle duration becomes powerful when you connect it directly to financial constraints and operating plans.

1) Set acquisition limits (CAC ceilings)

Duration informs LTV, and LTV sets the outer boundary for CAC. A practical (simplified) relationship is:

If you already track ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account) and gross margin, duration is the missing lever.

A working founder rule:

- If duration is uncertain, tighten CAC and bias toward channels with faster payback.

- If duration is reliably improving by cohort, you can cautiously raise CAC—while monitoring CAC Payback Period and cash runway.

2) Decide whether to push annual plans

Annual billing often improves cash flow and can reduce "impulse churn," but it can also hide weak product value until renewal.

Use lifecycle duration to answer:

- Are monthly customers churning before month 6? Annual might be a bad "band-aid" unless onboarding improves.

- Do customers who reach month 3 almost always renew? Annual can be a good fit, especially with the right upgrade path.

Also watch how annual impacts accounting and cash timing (see Deferred Revenue).

3) Prioritize retention work with leverage

Duration tells you where work pays off most:

- If median duration is low (e.g., 3–5 months), focus on activation, onboarding completion, and expectation-setting.

- If median is decent but long tail is weak, focus on expansion paths and ongoing ROI.

- If renewal cliffs dominate, focus on renewal process, champion enablement, and proof-of-value reporting.

4) Forecast with less self-deception

Founders often forecast using topline growth rates and ignore lifecycle duration. That's how you end up surprised by a churn wave six months later.

A more grounded approach:

- Build forecasts by cohort survival (how many accounts remain active) and combine with revenue retention (GRR (Gross Revenue Retention) and NRR (Net Revenue Retention)).

- Separate logo survival from revenue survival. You can have stable logo duration but improving revenue outcomes via expansion (see Expansion MRR and Net MRR Churn Rate).

How to improve lifecycle duration

Improving duration is less about "retention initiatives" and more about removing specific failure modes. Here's a practical playbook founders can run in weeks, not quarters.

Step 1: lock the definition and reporting

- Decide: first paid → churn effective date.

- Report median duration plus 12-month survival by segment.

- Keep a separate "signup-to-churn" metric if you need it, but don't mix it into revenue decisions.

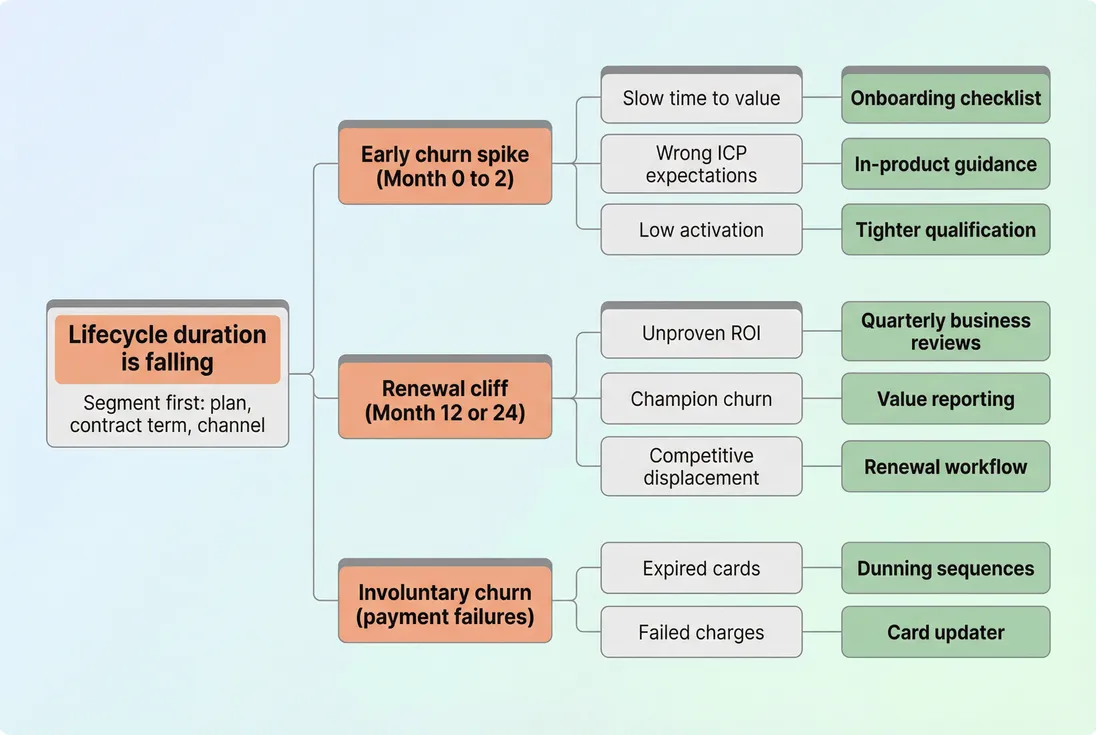

Step 2: find your dominant churn shape

Use retention cohorts to determine whether churn is:

- front-loaded (onboarding/value realization),

- renewal-driven (annual cliff),

- or operational (involuntary churn).

This is where cohort charts beat blended churn rates. If you need a refresher on interpreting cohort patterns, start with Cohort Analysis.

Step 3: fix the highest-leverage driver

High-leverage fixes by pattern:

Early churn spike

- Tighten acquisition targeting (fewer bad-fit customers beats better persuasion).

- Improve time-to-value: remove steps, add templates, reduce setup friction.

- Align expectations in marketing and sales. Overpromising reduces duration even if the product is decent.

Renewal cliff

- Build a repeatable renewal motion: start 90 days before term ends.

- Make ROI visible. Customers don't renew "features," they renew outcomes.

- Track champion risk and multi-thread relationships (especially in mid-market).

Involuntary churn

- Dunning, card updater, and "grace period" policies can increase duration without changing product.

- Keep involuntary churn separate so you don't confuse billing ops wins with product wins.

Step 4: validate improvements by cohort, not anecdotes

The only credible proof that lifecycle duration improved is:

- newer cohorts retain better at the same month offsets (Month 1, Month 3, Month 6),

- within the same segment definition.

Anecdotes ("CS says customers are happier") can be supportive, but not decisive.

The Founder's perspective: I treat lifecycle duration improvements as a financing event. If new cohorts survive longer, my future cash flows are more reliable—and I can choose to reinvest more aggressively in growth.

Practical benchmarks (use with caution)

Use these as "sanity checks," not targets. Contract structure and segment mix dominate outcomes.

| Segment (typical) | Billing | Typical median duration range |

|---|---|---|

| Consumer / prosumer tools | monthly | 2–6 months |

| SMB self-serve | monthly | 8–18 months |

| SMB to mid-market | monthly or annual | 12–30 months |

| Mid-market B2B | annual | 24–48 months |

| Enterprise | annual / multi-year | 36–84 months |

If your duration is below these ranges, don't jump straight to "the product is bad." First confirm:

- you're measuring from first paid,

- you're not mixing segments,

- and you're not counting involuntary churn as product churn without separating it.

Common pitfalls to avoid

- Blending monthly and annual customers. Annual customers "look" longer-lived even if renewals are weak.

- Ignoring censoring (active customers). Early-stage averages from churned-only customers will understate duration.

- Confusing revenue retention with logo retention. Expansion can mask short logo duration in revenue metrics; track both (see Logo Churn and NRR (Net Revenue Retention)).

- Treating discounts as free growth. Heavy discounting can shorten lifecycle if customers never anchor on full value (see Discounts in SaaS).

The metric in one sentence

Customer lifecycle duration is the clearest single indicator of how long your growth "sticks"—and when you measure it by cohort and segment, it becomes a practical tool for setting CAC limits, choosing contract terms, and prioritizing retention work that actually moves the business.

Frequently asked questions

Customer lifecycle duration is the time a customer stays active in a defined lifecycle window, usually from first paid date to churn date. Customer lifetime is often used similarly, but teams sometimes mix in pre-revenue stages like trial or sales cycle. Be explicit: define start, end, and whether you report mean or median.

Benchmarks vary more by segment and contract terms than by product category. Self-serve monthly SMB might target 8 to 18 months. Annual mid-market is often 24 to 48 months. Enterprise can be 36 to 84 months. Use your own cohorts and segment mix, not a single industry number.

Duration can drop because your customer mix changed, not because retention got worse. Examples: more low-intent signups, heavier discounting, shorter contract terms, or moving upmarket without fixing onboarding. Always segment by plan, acquisition channel, and first invoice size before concluding you have a product problem.

For revenue planning and LTV, start at first payment because that defines a revenue-producing customer and aligns with churn and retention metrics. If you are diagnosing funnel issues, track a separate lifecycle from signup to churn. Mixing the two makes duration look worse when onboarding takes longer or sales cycles expand.

Duration drives LTV and determines how long you have to earn back CAC. If your gross margin and ARPA are stable, a 20 percent increase in duration roughly yields a 20 percent increase in LTV. That can justify higher CAC or larger sales investment, but only if payback stays within your cash constraints.