Table of contents

Contribution margin

If you're growing revenue but your cash position keeps getting worse, contribution margin is usually the missing explanation. It tells you whether each incremental dollar of revenue creates real "fuel" to reinvest (in sales, marketing, and product) or whether growth is quietly increasing the cost to serve.

Contribution margin is the percentage of revenue left after you subtract the variable costs required to deliver that revenue. In plain terms: for every $1 you bring in, how many cents remain to pay fixed costs (team, rent, R&D) and still produce profit.

What contribution margin reveals

Founders use contribution margin to answer a very practical question:

Is growth making the business stronger, or just bigger?

A SaaS company can show strong top-line growth (see MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue) and ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue)) while becoming less scalable underneath. Contribution margin surfaces the scalability story by focusing on variable cost drag.

It's especially useful when:

- Infrastructure costs scale with usage (API-heavy, data-heavy, AI-heavy, usage-based pricing).

- Support and onboarding effort scales with customer complexity.

- Payment fees, refunds, or chargebacks fluctuate with plan mix and billing terms.

- You're considering new segments (SMB vs mid-market vs enterprise) that have different cost-to-serve profiles.

The Founder's perspective

If you can't explain contribution margin by segment, you're flying blind on pricing and GTM. You might be "winning" more customers who are structurally unprofitable, then compensating by raising funding or cutting headcount later.

How it's calculated

At its simplest, contribution margin is revenue minus variable costs, expressed as a percentage of revenue.

Two notes that matter in real SaaS operations:

Revenue should match the same period as costs. If you evaluate monthly contribution margin, use the month's revenue and the month's variable costs required to deliver it. If you use recognized revenue, align to recognized costs. If you use billed revenue, be consistent (and understand distortions from annual prepay).

Variable costs must be defined consistently. Contribution margin is not one universal standard. The power comes from choosing a definition that matches your decisions.

What counts as variable costs (and what doesn't)

Variable costs are costs that increase (directly or meaningfully) as revenue or customer activity increases. Fixed costs don't scale in the short term (or step-function later).

Here's a practical SaaS-oriented breakdown.

| Cost item | Usually variable? | Include in contribution margin? | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cloud hosting and compute | Often | Yes | Especially if tied to usage or customer count |

| Third-party API fees | Often | Yes | E.g., email sending, SMS, enrichment, LLM calls |

| Customer support labor | Sometimes | Depends | If support load scales with customers or usage, include an allocated variable portion |

| Onboarding / implementation | Sometimes | Depends | Common to include for enterprise or high-touch motions |

| Payment processing fees | Yes | Yes | Also consider billing fees and interchange effects |

| Chargebacks and refunds | Yes | Yes | See Refunds in SaaS and Chargebacks in SaaS |

| COGS (accounting category) | Mixed | Often | Helpful starting point: see COGS (Cost of Goods Sold) |

| Sales commissions | Variable | Optional | Include for "GTM contribution margin," exclude for "product contribution margin" |

| Sales and marketing salaries | Usually fixed | No | Typically treated as fixed or semi-fixed operating costs |

| Product and engineering salaries | Fixed | No | Not part of contribution margin |

Two common definitions you should choose between

Most teams end up tracking two layers, because they answer different questions:

- Product contribution margin (service margin): revenue minus costs to deliver the product/service (hosting, tooling, support, payment fees).

- GTM contribution margin: product contribution profit minus variable selling costs (commissions, per-deal onboarding, partner rev share).

Neither is "right." What's dangerous is mixing definitions month to month.

The Founder's perspective

Use product contribution margin to validate pricing and delivery scalability. Use GTM contribution margin to decide whether to scale a motion (PLG, SLG, partners) and to sanity-check CAC payback under real cost-to-serve conditions.

A concrete example (what the number means)

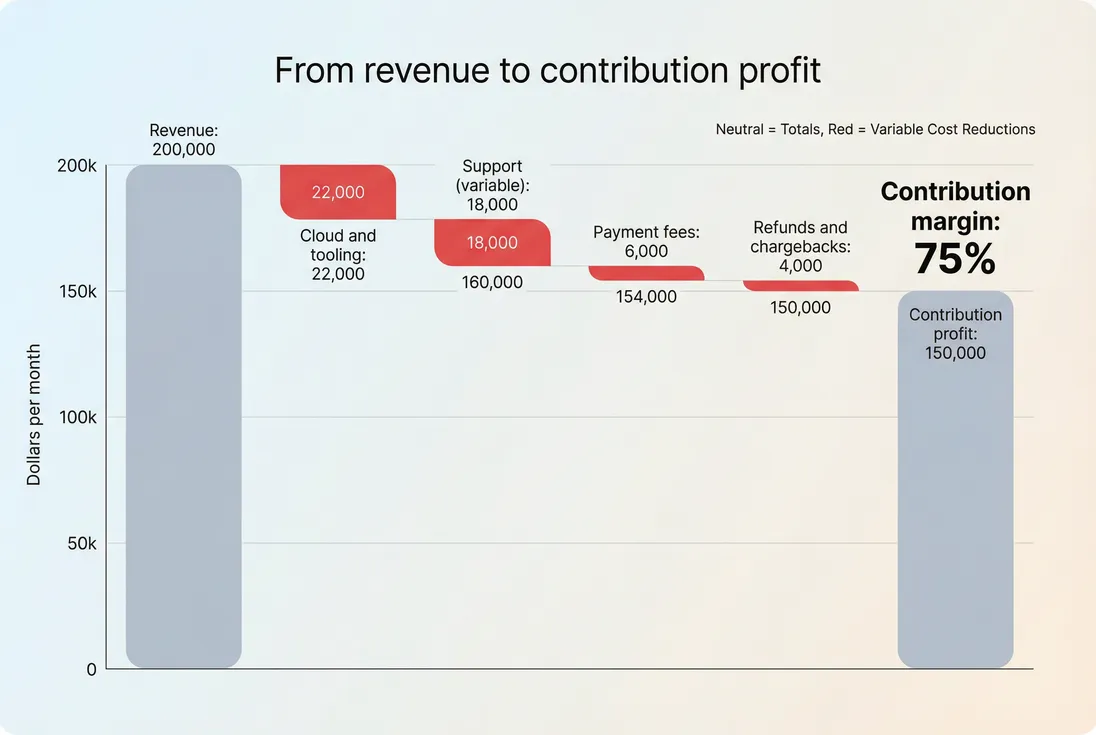

Assume in a month you have:

- Revenue: $200,000

- Variable costs:

- Cloud and data tooling: $22,000

- Support (variable allocation): $18,000

- Payment processing: $6,000

- Refunds and chargebacks: $4,000

Variable costs total: $50,000

Contribution profit: $150,000

Contribution margin: 75%

Interpretation: each incremental $1.00 of revenue generates $0.75 to cover fixed costs and profit. If your fixed costs are $160,000, you're still losing money (operating loss) even though contribution margin is strong. That's normal at certain stages—but the margin tells you whether scaling revenue will tend to improve the situation.

What moves contribution margin up or down

Contribution margin changes for specific, operational reasons. The trick is to translate the percentage movement into a root cause you can act on.

Drivers that usually increase it

- Price increases that stick (especially if costs don't rise with price).

- Packaging changes that shift customers into higher-margin plans.

- Lower payment fees via annual prepay mix or cheaper rails (where feasible).

- Improved infrastructure efficiency (cost per event, cost per seat, cost per workspace).

- Support deflection (better docs, in-product guidance) that reduces variable support load.

- Better customer fit (fewer high-maintenance accounts with low ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account)).

Drivers that usually decrease it

- Discounting and custom deals that reduce revenue without reducing delivery costs (see Discounts in SaaS).

- Usage growth without pricing alignment (classic in Usage-Based Pricing when unit costs rise faster than unit revenue).

- Higher refund and chargeback rates (often a symptom of mis-selling or billing issues).

- Support and onboarding ballooning in a segment that wasn't designed for high-touch delivery.

- Customer mix shift toward lower-priced plans with similar cost-to-serve.

The "hidden" driver: accounting classification

If your finance team reclassifies costs between COGS and operating expenses, gross margin might move while contribution margin (if defined independently) stays consistent—or vice versa. This is why it's helpful to understand both contribution margin and Gross Margin and keep a reconciliation.

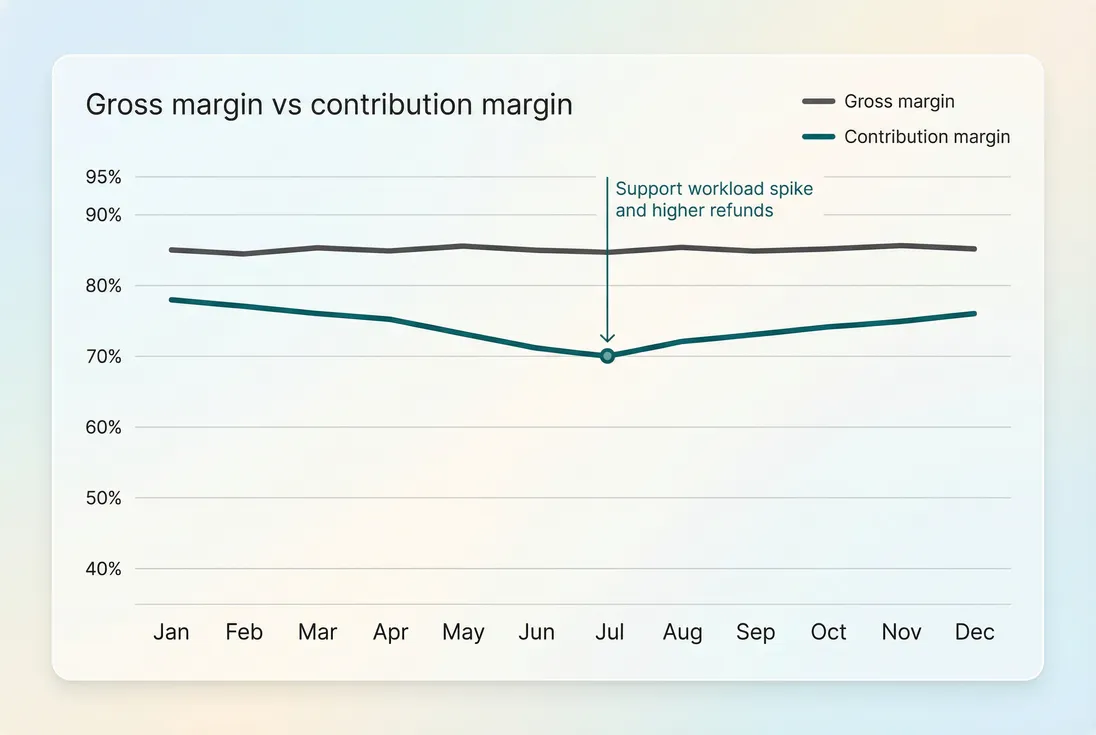

Contribution margin vs gross margin vs operating margin

These metrics answer different questions:

- Gross margin: accounting view of profitability after COGS. Useful for comparability and financial reporting.

- Contribution margin: unit economics view after variable costs. Useful for pricing, segmentation, and scale decisions.

- Operating margin: full business profitability after operating expenses. Useful for runway and profitability targets (see Burn Rate and Operating Margin).

A common founder mistake is using gross margin as a proxy for "scalability" when support, onboarding, and usage costs sit outside COGS. Contribution margin is where you capture those realities—if you define it that way.

How founders use it in real decisions

Contribution margin becomes powerful when it's used as a decision guardrail, not just a reporting number.

1) Pricing and packaging decisions

When deciding whether to raise prices or change packaging, contribution margin tells you whether the extra revenue drops to the bottom line or gets eaten by cost-to-serve.

Practical approach:

- Estimate how revenue changes by plan.

- Estimate how variable costs change by plan (especially usage-driven costs).

- Model contribution profit impact, not just top-line impact.

If you're evaluating per-seat pricing, contribution margin by seat tier is often more actionable than overall margin. Pair this with ASP (Average Selling Price) to understand how deal sizes translate into real profit.

2) CAC payback and growth pacing

Founders often track CAC Payback Period using gross margin assumptions. If your variable costs are meaningfully higher than COGS (support-heavy, onboarding-heavy, usage-heavy), you'll understate payback time.

A tighter version of the question is:

- "How many months of contribution profit does it take to recover CAC?"

That pushes you toward more sustainable scaling and prevents "growth that increases burn."

This connects directly to Burn Multiple and broader Capital Efficiency: higher contribution margin generally improves efficiency, but only if retention holds.

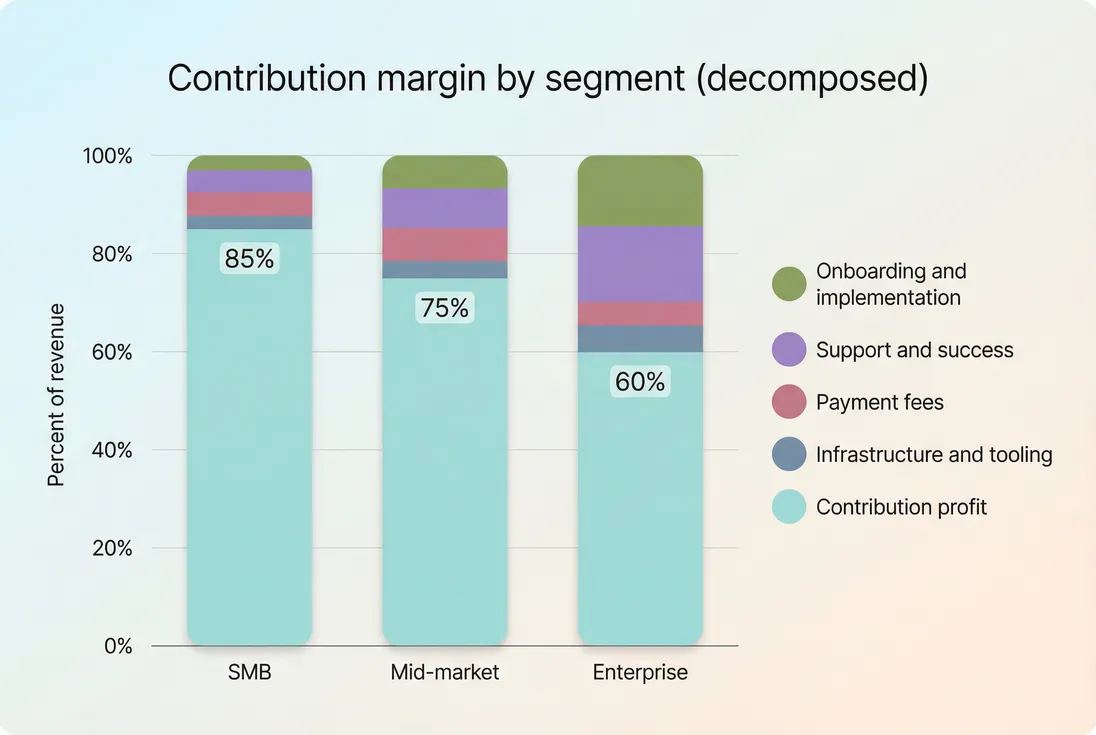

3) Segment strategy (which customers to pursue)

Two customers can pay the same amount and have radically different variable cost footprints. Segmenting contribution margin by:

- plan tier,

- acquisition channel,

- use case,

- customer size band,

often changes priorities quickly.

This is where retention and churn tie in: if a segment has lower margin and higher churn, it's usually a double problem. Use Cohort Analysis alongside churn metrics like Logo Churn and Net MRR Churn Rate to validate whether the segment is compounding or draining.

4) Product and infrastructure investments

When contribution margin is pressured by usage costs, you have a clear ROI frame for engineering work:

- Reduce compute per unit of customer activity.

- Reduce third-party API calls per workflow.

- Improve caching, batching, and data retention policies.

- Adjust limits and packaging so heavy usage is paid for.

This is one of the cleanest ways to justify work that might otherwise feel like "internal optimization." Contribution margin translates it into dollars.

5) Sales motion design

If you sell higher ACV deals, you might accept lower product contribution margin if:

- retention is materially better,

- expansion is strong,

- onboarding cost is front-loaded and repeatable.

But you should measure it explicitly. Tie margin by segment to:

- Average Contract Length (ACL) (longer contracts can absorb onboarding cost),

- renewal behavior (see Renewal Rate),

- and expansion (see Expansion MRR).

Benchmarks and what "good" looks like

There's no single universal benchmark because variable cost structure varies a lot. Still, ranges help you sanity-check.

| SaaS type | Typical contribution margin tendency | Why |

|---|---|---|

| Self-serve SMB SaaS | Higher (often 80–90%+) | Low touch support and onboarding, predictable infra |

| Mid-market SaaS | Mid to high (70–85%) | More support and success cost, more integrations |

| Enterprise / implementation-heavy | Wider range (50–80%) | Onboarding and support can be substantial and deal-specific |

| Usage-heavy (data, API, AI) | Highly variable | Unit costs can spike unless pricing matches usage |

Use benchmarks as a starting point. What matters is:

- trend over time, and

- margin by segment and plan, not just blended margin.

The Founder's perspective

Don't optimize for the best-looking blended margin. Optimize for a model where margin stays stable or improves as you scale. If your best customers subsidize your worst customers, growth can amplify the problem.

How to track contribution margin without fooling yourself

Match costs to the right revenue

Contribution margin is easy to distort when revenue timing and cost timing don't line up.

Common traps:

- Annual prepay boosts cash and billed revenue, but support and infrastructure happen monthly.

- One-time onboarding fees inflate a month's revenue without changing long-run unit economics.

- Refunds and chargebacks can hit later than the original revenue.

If you're analyzing subscription performance, consider pairing contribution margin analysis with Recognized Revenue concepts and keep a clear policy for how you attribute refunds (see Refunds in SaaS).

Treat taxes correctly

Taxes like VAT are usually pass-through amounts, not revenue. If you include VAT in revenue, your margin will look artificially low. See VAT handling for SaaS to keep the revenue base clean.

Segment early, not after problems appear

If you only look at a single blended contribution margin, you won't see:

- low-margin plans,

- high-refund channels,

- expensive-to-serve integrations,

- or specific customer types that drive support load.

In practice, teams often start by segmenting by:

- plan tier,

- geography (tax and payment fees),

- customer size band (proxy: ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account)),

- and acquisition motion (PLG vs sales-led).

If you're already tracking revenue movements, tools like GrowPanel's MRR movements and filters can help you isolate where the revenue change came from; you'll still need to bring in cost data to compute contribution margin, but segmentation discipline carries over.

Common mistakes (and how to avoid them)

Including fixed salaries as variable costs.

If your support team is salaried and not scaling with customers today, you can't treat it as fully variable. Better: allocate only the portion that genuinely scales (or track a separate "support cost per customer" and revisit as headcount changes).Ignoring refunds and billing leakage.

If refunds spike, your "revenue quality" is worse than your MRR suggests. Treat refunds and chargebacks as variable costs that reduce contribution profit. Also review Billing Fees if fees are material.Not updating unit costs after architecture changes.

A new data pipeline, AI feature, or third-party dependency can change unit economics overnight. Re-baseline contribution margin assumptions when you change your cost structure.Mixing definitions between teams.

Finance might define contribution margin one way (COGS-focused), while RevOps defines it another (includes commissions). Choose names that make this explicit: "product contribution margin" and "GTM contribution margin."Blended averages hiding cohort issues.

Newer cohorts might be less profitable due to heavier onboarding, higher support, or more discounts. Pair contribution margin views with Cohort Analysis so you can see whether newer acquisition is structurally weaker.

A simple operating cadence for founders

If you want this metric to drive decisions (not just reporting), use a lightweight cadence:

- Monthly: Track overall contribution margin and top 2–3 drivers (payment fees, infra, support, refunds).

- Monthly segmentation: By plan tier and customer size band.

- Quarterly deep dive: Reassess variable cost assumptions and identify margin leaks (pricing, limits, onboarding scope creep).

- Before scaling spend: Sanity-check CAC payback using contribution profit, not just gross margin.

This puts contribution margin where it belongs: as a guardrail for growth and a spotlight on scalability.

The bottom line

Contribution margin tells you whether revenue is high-quality and scalable. If it's stable or improving as you grow, you have a model that can compound. If it's declining, you don't just have a cost problem—you likely have a pricing, packaging, customer mix, or delivery model problem.

When founders treat contribution margin as a living operational metric (segmented, trended, and tied to CAC payback and retention), it becomes one of the fastest ways to catch unscalable growth early—and fix it before it shows up as a cash crisis.

Frequently asked questions

For most SaaS, a healthy product contribution margin often lands in the 70 to 90 percent range, depending on hosting, support, and third party tooling. What matters more is trend and segment mix. If margin drops as you grow, your model may not scale.

Gross margin typically subtracts COGS as reported in accounting. Contribution margin subtracts variable costs tied to serving customers, which may include payment processing, variable support, and infrastructure that scales with usage. Many teams track both, then reconcile definitions so decisions remain consistent.

It depends on how you use the metric. If you want product economics, exclude commissions and keep them in CAC and sales expense. If you want go to market contribution (per customer or per segment), include commissions and other variable selling costs to see if each deal funds itself.

Common causes are discounting, higher payment fees from plan mix, usage driven infrastructure costs, onboarding and support effort rising with customer complexity, or refunds and chargebacks. Segmenting by plan and customer size usually reveals the driver. Also confirm costs are matched to the same period as revenue.

Use it to set guardrails for scaling spend. If contribution profit per customer is thin, aggressive acquisition can increase burn without building reinvestable cash. Tie contribution margin to CAC payback and retention. A stable or improving margin supports scaling; a declining margin demands pricing or cost fixes first.