Table of contents

Burn rate

Burn rate is the number that turns strategy into a deadline. You can have strong product momentum, a healthy pipeline, and happy customers—and still fail if cash runs out before momentum converts into durable recurring revenue.

Burn rate is how much cash your company is losing per month. In SaaS, founders usually mean net burn: cash out minus cash in, measured over a month (or averaged over several months).

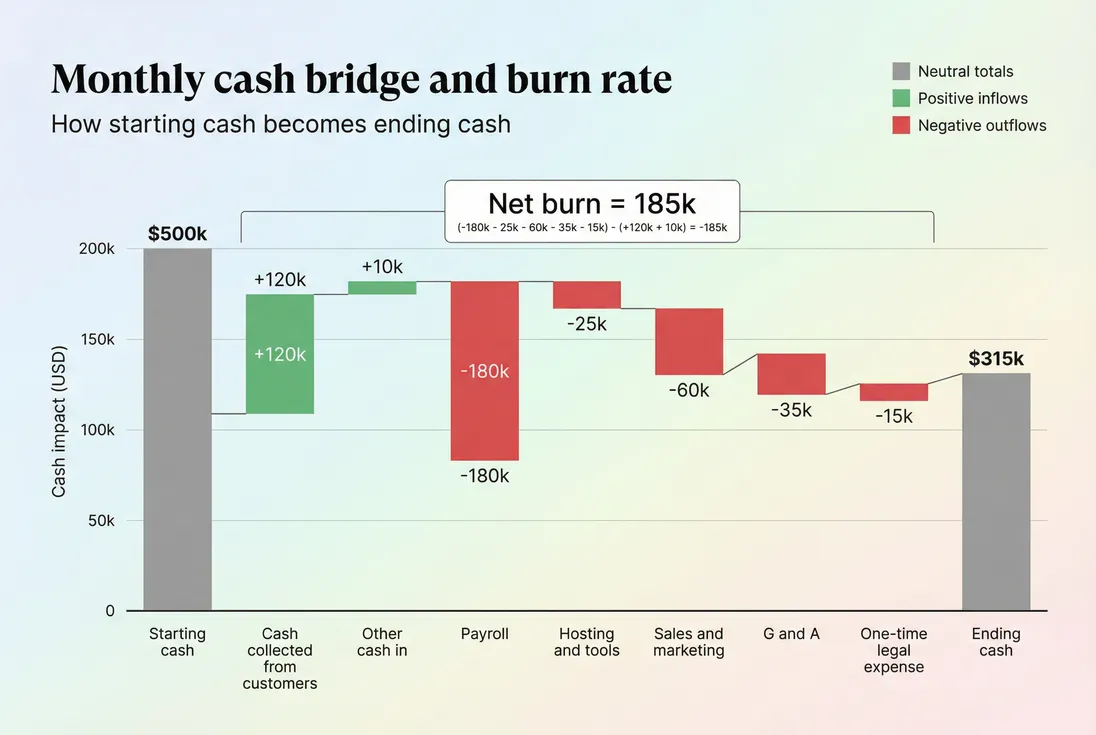

A cash bridge makes burn intuitive: what came in, what went out, and what that means for ending cash.

What burn rate actually measures

Burn rate is not a vanity metric. It's a constraint metric: it tells you how much time your current plan buys.

There are two common versions:

Gross burn vs net burn

- Gross burn = total cash paid out in a month (payroll, rent, cloud, contractors, ads, etc.).

- Net burn = cash paid out minus cash collected in the month.

Founders care about net burn because it drives how fast the bank balance shrinks. But gross burn matters because it reveals your cost structure and how reversible your spend is.

Use both:

- Gross burn answers: "How expensive is this machine to run?"

- Net burn answers: "How fast are we running out of fuel?"

Cash burn vs accounting loss

Your P&L can mislead you—especially in SaaS.

- P&L loss is accounting-based (accrual). It includes non-cash items and revenue recognition timing.

- Cash burn is cash-based. It's what hits the bank.

Examples where they diverge:

- Annual prepayments: Cash goes up now, but revenue is recognized over time (see Deferred Revenue and Recognized Revenue).

- Unpaid invoices: Revenue shows on the P&L, but cash hasn't arrived yet (see Accounts Receivable (AR) Aging).

- Non-cash expenses: Depreciation or stock compensation impact accounting profit but not immediate cash.

If you're managing survival, cash burn wins.

The Founder's perspective

If you're debating hiring, paid acquisition, or extending runway, you are not making a "financial reporting" decision—you are making a cash timing decision. Burn rate is the scoreboard for that game.

How to calculate burn rate

At its simplest, calculate net burn from bank-account reality:

Where:

- Cash paid out includes payroll, vendors, cloud, ads, taxes paid, etc.

- Cash collected includes subscription payments received, annual prepayments, usage overages collected, and services collected.

A more finance-accurate approach

If you have a cash flow statement, use "net cash used in operating activities" (and decide whether you also include investing activities like equipment purchases):

Many SaaS teams include modest investing (laptops, minor equipment) because it's real cash leaving the business. The key is consistency.

Don't rely on a single month

Monthly cash is noisy. A cleaner operating view is a trailing average:

This pairs well with a smoothing concept like T3MA (Trailing 3-Month Average), especially if you bill annually or have lumpy enterprise collections.

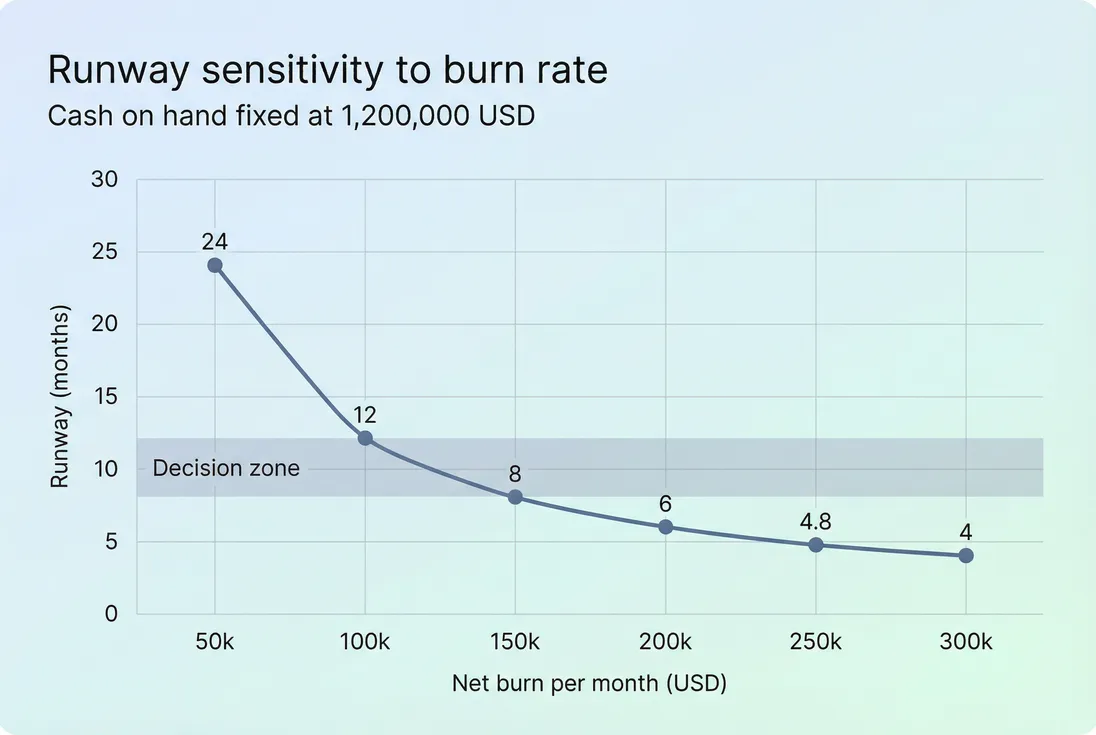

Runway is the burn rate's "so what"

Runway turns burn into a timeline:

If you want the broader framing (and pitfalls), see Runway. Burn rate is the input; runway is the decision variable.

Quick example

- Cash on hand: $900,000

- Average net burn (last 3 months): $150,000 per month

Runway:

Six months is not "fine" unless you can reliably raise quickly or flip to breakeven quickly. It's a forcing function.

What typically drives burn in SaaS

Burn is just a symptom. The job is understanding the levers behind it.

1) Headcount and payroll gravity

For most SaaS companies, payroll dominates burn. This makes burn rate sticky:

- Hiring ramps cost immediately.

- Productivity gains take time.

- Layoffs reduce burn, but with morale, severance, and execution costs.

A useful internal view is burn per function:

- Product and engineering

- Sales

- Marketing

- Customer success

- G&A

If burn rose, ask: did we add headcount, increase compensation, or add contractors? Then ask whether the added spend is producing leading indicators (pipeline, activation, retention) or just activity.

2) Gross margin and COGS surprises

Burn is heavily influenced by your ability to turn revenue into cash contribution.

If gross margin is weak, growth can increase burn instead of reducing it. Review:

Common SaaS margin killers:

- Cloud infrastructure scaling faster than revenue

- Heavy human services bundled into "software"

- Vendor tooling sprawl

3) Go-to-market efficiency

Sales and marketing is where burn often goes to die—especially with long cycles.

Tie burn discussions to:

A classic failure mode: you scale paid acquisition or SDR headcount before you have stable conversion rates and retention. Burn rises; revenue lags.

4) Retention and expansion (burn's hidden engine)

Burn often looks like a cost problem, but it's frequently a retention problem.

If churn rises, you lose the compounding effect of recurring revenue. Track:

If you use GrowPanel's allowed revenue tooling, a practical way to connect burn to reality is to review MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue) and the underlying drivers in MRR movements—new, expansion, contraction, and churn. Burn becomes easier to defend (or cut) when you can point to which revenue motion is failing.

5) Working capital: the "burn rate illusion"

Two SaaS companies can have identical P&Ls and very different burn because cash timing differs.

Watch for:

- Annual upfront billing: reduces near-term net burn (cash comes in early), even if the business isn't healthier.

- AR collections: collecting overdue invoices makes burn look better temporarily (see Accounts Receivable (AR) Aging).

- Refunds and chargebacks: can spike burn unexpectedly (see Refunds in SaaS and Chargebacks in SaaS).

- Billing fees and taxes: small individually, meaningful at scale (see Billing Fees and VAT handling for SaaS).

This is why founders should separate "burn improved because operations improved" from "burn improved because cash timing improved."

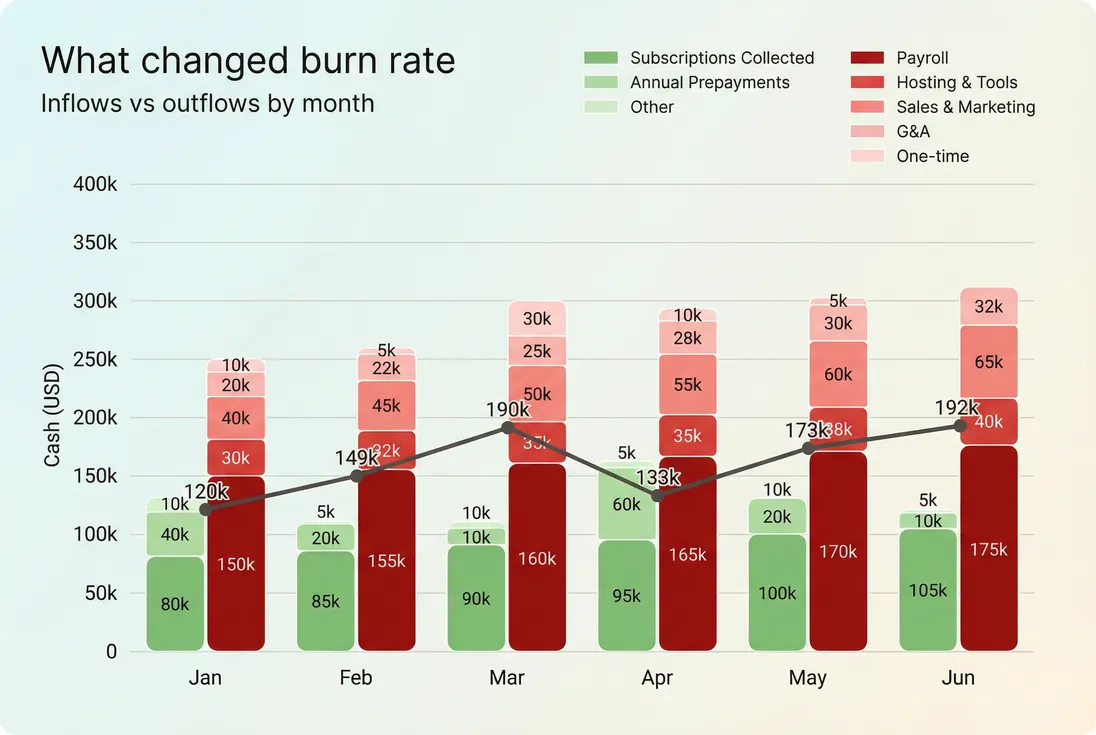

Separating inflows from outflows shows whether burn changed because you spent less, collected more, or both.

How to interpret burn rate changes

Burn rate is easy to compute and easy to misread. Here's how to interpret it without fooling yourself.

When burn increases

An increase is not automatically bad. It depends on whether you bought something that predictably compounds.

Burn increases are defensible when:

- You hired for a proven motion (e.g., onboarding or a sales team with stable win rates).

- You scaled a channel with known payback.

- You invested in reliability or performance that reduces churn (see Churn Reason Analysis).

Burn increases are dangerous when:

- They fund experimentation without clear kill criteria.

- They precede measurable leading indicators (pipeline quality, activation, retention).

- They come from fixed commitments you can't unwind quickly.

A simple diagnostic: if burn went up, you should be able to name the metric you expect to move and the timeframe. If not, it's probably uncontrolled spend.

When burn decreases

Burn dropping can mean:

- You truly got leaner (reduced headcount, negotiated vendors, reduced cloud waste).

- You improved cash inflow quality (higher conversion, better retention, higher ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account), fewer discounts).

- You shifted timing (annual prepay, delayed bills, collected AR).

You care most about (1) and (2). Treat (3) as temporary.

A practical check:

- Did MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue) and retention improve?

- Did gross margin improve?

- Or did cash collections spike while core subscription momentum stayed flat?

Watch for "annual billing camouflage"

Annual contracts often make early-stage burn look artificially healthy because cash arrives upfront. That's not a reason to ignore burn; it's a reason to track it with context.

If you sell annual:

- Track net burn for runway.

- Also track a "normalized" view that flags big prepayments and one-time outflows.

This is also where the concept of Burn in SaaS is helpful: it frames burn as a system, not just a monthly subtraction.

The Founder's perspective

The most expensive mistake is thinking you reduced burn when you only improved cash timing. If your burn is "better" but churn is rising or pipeline is deteriorating, you didn't fix the engine—you just coasted downhill for a month.

How founders use burn rate to make decisions

Burn rate becomes powerful when it's tied to operating rules.

1) Set burn guardrails

Choose a runway floor that triggers action. Common guardrails:

- < 6 months runway: emergency mode (cost cuts or bridge capital now).

- 6–12 months runway: aggressive focus on efficiency; fundraising plan must be active.

- 12–18 months runway: healthier operating window; you can invest with discipline.

The right number depends on sales cycle length, retention strength, and market conditions. If you have long enterprise cycles, 12 months can be functionally short.

2) Tie spend to measurable proof

Before increasing burn, define:

- Leading indicator: pipeline created, activation, time-to-value, retention, expansion.

- Lagging indicator: ARR growth (see ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue)).

- Kill criteria: what must be true in 30/60/90 days to keep spending.

This prevents "burn drift," where costs ratchet up while accountability stays vague.

3) Plan hiring around burn, not optimism

A clean rule: hiring plans must be valid under a conservative revenue scenario.

Stress test:

- What if new bookings are 30% lower for two quarters?

- What if churn increases by 1–2 points?

- What if collections slow (AR days increase)?

If the plan breaks immediately, it's not a plan—it's a bet.

4) Use burn rate with efficiency metrics

Burn rate tells you speed of cash loss, but not quality of growth. Pair it with:

- Burn Multiple: how much cash you burn to create net new ARR.

- Capital Efficiency: broader lens on turning capital into durable revenue.

- Free Cash Flow (FCF): for later-stage SaaS, a more complete cash performance view.

A founder-relevant interpretation:

- If burn is high and burn multiple is poor, you have an efficiency problem.

- If burn is high but burn multiple is strong, you may have a timing problem (raise earlier) or simply be choosing speed.

- If burn is low but growth is also low, you may be under-investing or stuck pre-fit.

5) Decide when to cut versus raise

Burn rate becomes a decision tool when paired with fundraising reality.

A practical sequence:

- Compute 3-month average net burn and runway.

- Assume fundraising takes longer than you think.

- Decide whether you can hit a meaningful milestone before cash gets tight.

Milestones that help (depending on stage):

- Consistent retention improvements (NRR trending up)

- Shorter payback (see CAC Payback Period)

- Clear ICP and improved win rate (see Win Rate)

- Higher pricing power (see Price Elasticity and Discounts in SaaS)

If you cannot get to a milestone, cost reduction may be the only rational path.

Small burn changes create big runway changes—especially when you're already under 12 months.

When burn rate "breaks" (and how to fix it)

Burn rate gets misleading in a few predictable situations.

Annual prepay or big invoicing months

If one month includes large annual payments, net burn can look amazing—even negative. Fix: track both:

- Monthly net burn (for cash reality)

- 3-month average net burn (for operating trend)

Also flag large prepayments separately so you don't treat them as recurring operating strength.

One-time expenses

Security audits, legal work, one-off contractors, migration costs—these distort burn. Fix: track a "core burn" view:

- Core payroll + recurring vendors + ongoing cloud

- Exclude one-time items, but don't forget they're real cash (just not steady-state)

Fast-changing churn

A churn spike often hits burn with a delay: revenue drops, but costs lag. Fix: monitor churn weekly and connect it to your revenue engine:

If churn is rising, assume burn will worsen unless you cut or replace revenue quickly.

A practical burn rate operating rhythm

For most founders, the goal is not "perfect finance." It's a simple cadence that prevents surprises.

Weekly (15 minutes):

- Cash balance

- Collections vs expectations (especially if invoicing)

- Any unusual upcoming outflows (taxes, annual renewals)

Monthly (60 minutes):

- Net burn and 3-month average net burn

- Gross burn by function

- Runway update and forecast

- One decision: hold, invest, or cut

Quarterly:

- Re-baseline hiring plan and vendor stack to match your runway guardrail

- Re-check efficiency metrics like Burn Multiple and payback

Burn rate won't tell you what to build or how to sell. But it will tell you whether you have enough time to figure those out—and whether your current plan is buying time wisely.

Frequently asked questions

Burn rate is too high when it forces decisions on a timeline shorter than your product and go-to-market reality. If your current burn leaves less than 12 months of runway and you cannot credibly improve retention, pricing, or sales efficiency in one or two quarters, you are in the danger zone.

Track both. Gross burn tells you how much cash you are spending and is harder to manipulate with timing. Net burn tells you how quickly cash is shrinking after collections. Net burn drives runway, but gross burn is better for budgeting, headcount planning, and understanding whether you actually reduced spending or just pulled cash forward.

Most "mysterious" burn improvements come from timing: annual prepayments, delayed vendor bills, collecting overdue invoices, or pausing hiring. Check the cash flow statement and working capital movements. If MRR, retention, and gross margin did not improve, assume burn will revert next month.

Many founders aim for 12 to 18 months of runway after a fundraise, because fundraising itself can take 3 to 6 months and markets can turn quickly. If you are pre-product-market fit, prioritize flexibility. Post-fit, runway should reflect your confidence in predictable pipeline and retention.

Burn rate is cash spent per month. Burn multiple compares how much cash you burn to how much new recurring revenue you create, usually net new ARR. Burn rate tells you survival time; burn multiple tells you efficiency. You can have a "safe" burn rate but terrible efficiency, or vice versa.