Table of contents

ASP (Average Selling Price)

ASP is one of the fastest ways to tell whether you're building a "bigger deal" business or just adding more customers. If your ASP is drifting down, you may be quietly training the market to expect discounts, sliding into smaller customers, or over-indexing on low-tier plans—often without noticing until CAC payback gets ugly.

ASP (Average Selling Price) is the average amount of revenue you sell per deal (or per new customer) in a defined period, using a clearly defined revenue unit (typically new MRR, ACV, or first-year ARR).

ASP often moves opposite new-customer volume; the job is to confirm whether higher ASP improves unit economics or simply reflects fewer small deals.

What ASP reveals

Founders track ASP because it compresses several hard truths into one number:

- Pricing power: Are customers paying closer to list price, or are you "buying" deals with discounts?

- Customer mix: Are you moving upmarket (larger buyers) or downmarket (smaller buyers)?

- Packaging fit: Are customers landing in the plan you intended, or defaulting into a cheap tier?

- Sales efficiency: Does your deal size support your sales motion and your CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost)?

ASP is especially useful when paired with:

- ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account) to separate "new sales performance" from your overall installed base.

- MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue) movements to see whether higher ASP is actually driving more expansion later.

- CAC Payback Period to validate whether your average deal supports the cost to acquire it.

The Founder's perspective

If ASP is too low for your sales motion, nothing else really matters—your pipeline can look healthy while the business quietly becomes non-viable. ASP is the quickest "sanity check" against CAC and payback.

How to calculate ASP

ASP must be defined with two choices:

- What revenue unit are you averaging? (new MRR, ACV, first-year ARR, etc.)

- What is the denominator? (deals, new customers, new subscriptions)

Most SaaS teams use one of these definitions:

ASP for self-serve or subscription signups (new MRR basis)

Use this when customers typically start monthly and expand later.

Practical interpretation:

- ASP rises if new customers choose higher tiers, buy more seats, or accept fewer discounts.

- ASP falls if you attract smaller customers, introduce a cheaper plan, or discount more.

ASP for sales-led deals (ACV basis)

Use this when you sell annual contracts (or you think and forecast in annual terms).

If contract lengths vary, be explicit about whether you mean:

- ACV (annualized contract value), or

- Total contract value (TCV)

A common rule: ASP should match the number your team actually operates on. If sales comp is based on ACV, compute ASP on ACV. If your cash planning depends on annual prepay, you may track both ACV and cash-in.

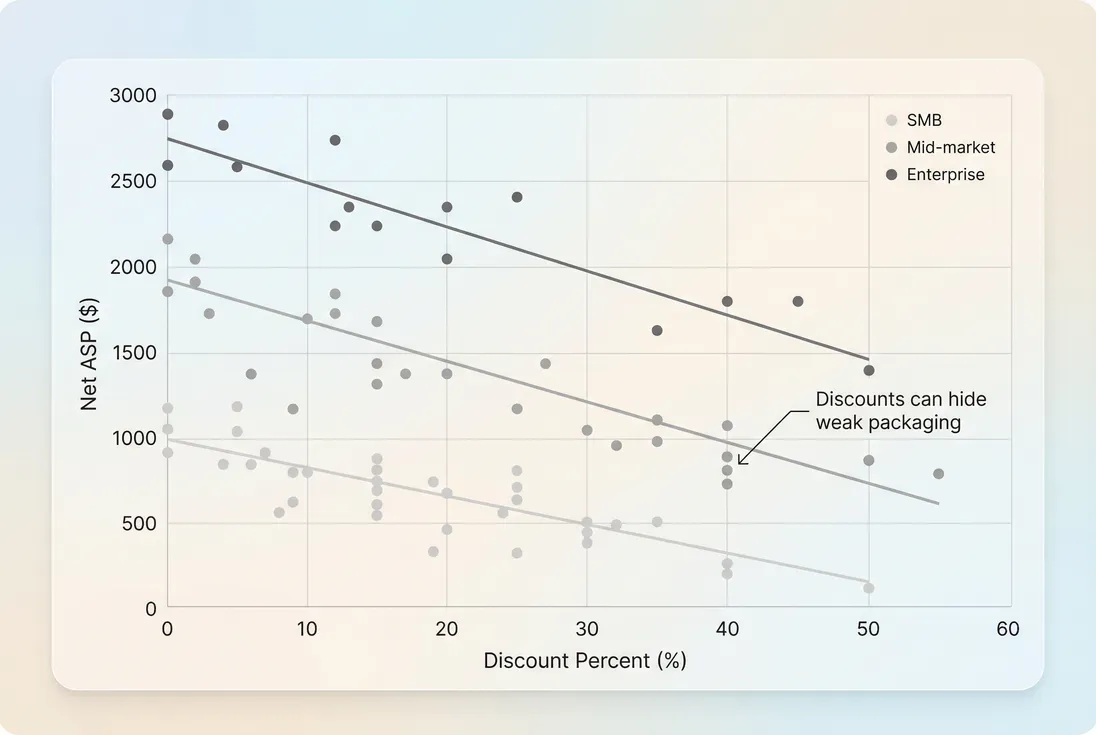

Net vs gross ASP (discounts)

ASP is most decision-useful when it reflects what you actually collect:

If you want to manage pricing discipline, track gross ASP (list price) and net ASP (after discount) separately, and tie the gap to your discount policy. For more on mechanics and tradeoffs, see Discounts in SaaS.

What moves ASP up or down

ASP is not just "pricing." It's the combined output of pricing, packaging, targeting, and deal execution. When it changes, you want to attribute the change to a small set of drivers.

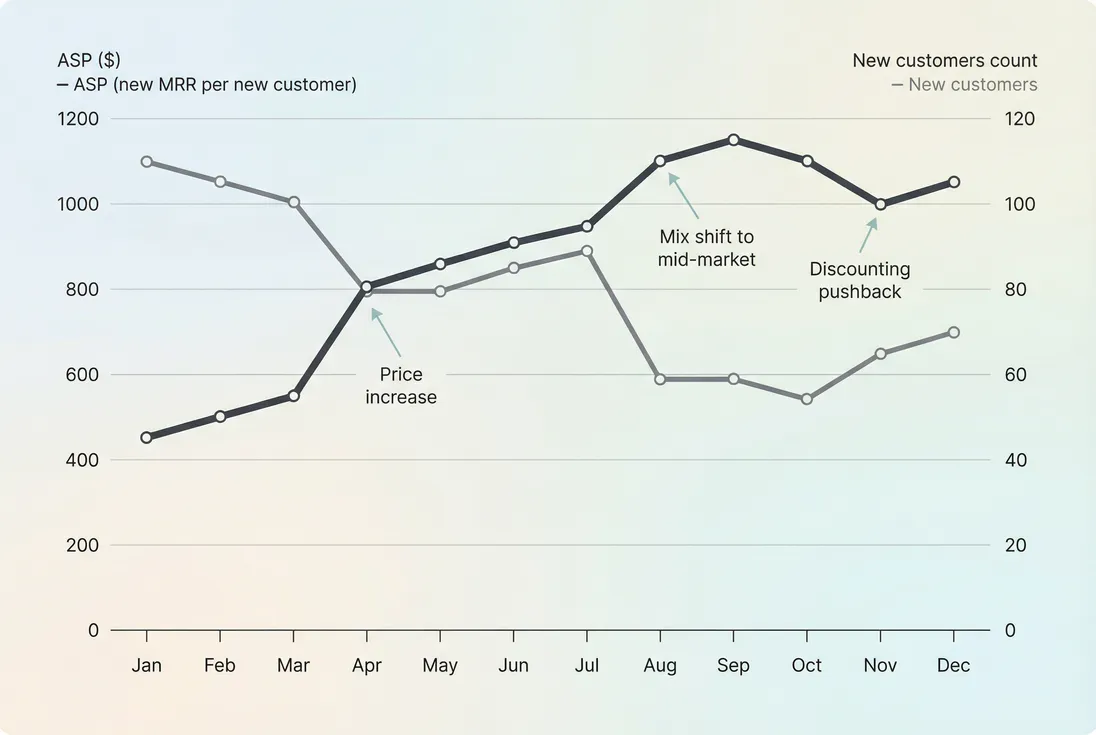

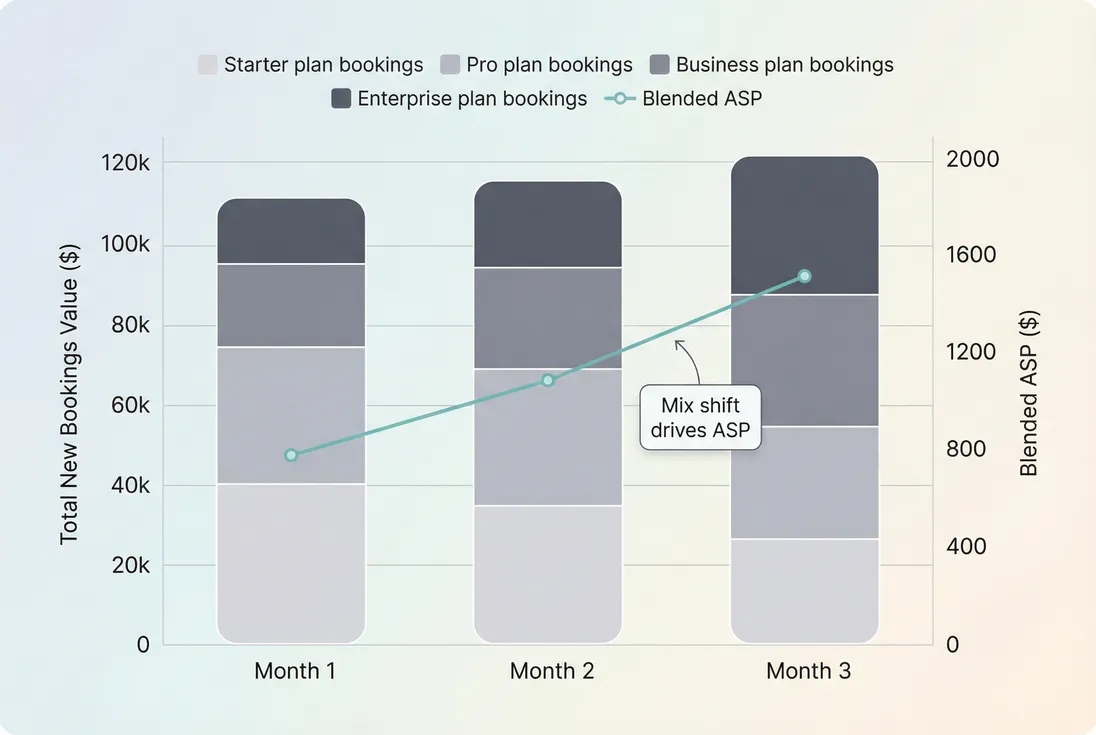

1) Mix shift (who you're selling to)

A classic ASP increase is not a price increase—it's a shift toward bigger customers:

- New inbound becomes more "manager" and less "founder."

- More deals come from outbound to larger accounts.

- Fewer tiny customers start, but each win is larger.

The risk: you can "grow" ASP while shrinking the top of funnel and total logos, which may slow compounding expansion later.

How to diagnose:

- Break ASP by segment (SMB vs mid-market vs enterprise).

- Compare segment share of new customers month-over-month.

- Track win rate and sales cycle by segment (ASP often rises with longer cycles).

Useful companion metrics: Sales Cycle Length, Win Rate.

2) Packaging and plan design

ASP moves when the default plan changes—even if pricing doesn't.

Common packaging-driven ASP drops:

- Adding a low-priced entry plan that becomes the "safe choice."

- Moving a core feature into a higher tier but failing to communicate value (prospects stall, or choose lower tier).

- Creating too much room in the cheapest tier (customers never need to upgrade).

Common packaging-driven ASP increases:

- Better tier boundaries that match real usage.

- Stronger upgrade paths tied to value triggers (seats, usage, workflow complexity).

This is especially tied to Per-Seat Pricing and Usage-Based Pricing. In both models, ASP should be evaluated alongside activation and expansion behavior—not just initial checkout.

3) Discounting and deal hygiene

Discounting changes ASP immediately, but the real question is why discounting is happening:

- To win competitive bake-offs?

- To compensate for missing product capabilities?

- To overcome procurement friction?

- Because reps are untrained and default to discounting?

What to watch:

- Discount rate by rep, segment, and deal size.

- ASP trend for "same segment, same plan" deals (controls for mix).

If ASP rises because you reduced discounts, it's often a high-quality improvement—as long as win rate and retention don't deteriorate.

4) Contract structure and billing terms

ASP can "look" higher due to contract mechanics rather than true pricing strength:

- Annual prepay vs monthly (cash timing changes, value may not).

- Multi-year deals (TCV rises, ACV might not).

- One-time fees bundled into the first invoice.

Be careful not to mix apples:

- Keep recurring ASP separate from onboarding/implementation fees if you're using it to reason about recurring unit economics.

- Align definitions with ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue) and ACV (Annual Contract Value) to avoid inconsistent baselines.

How founders use ASP for decisions

ASP becomes powerful when it drives specific operational actions, not just reporting.

1) Pricing changes: validate, don't guess

A price increase should show up as:

- Higher net ASP for new customers (fastest signal)

- Stable conversion/win rate, or a manageable decline offset by higher revenue

A useful way to frame the decision:

- If ASP rises 20% but new-customer volume falls 10%, revenue from new customers is still up.

- But if volume falls 40%, you may have over-shot price elasticity or messaging.

Pricing decisions also affect downstream retention. If you raise price and customers churn faster, your apparent ASP win may be offset by lower LTV (Customer Lifetime Value).

The Founder's perspective

I don't need ASP to be "high." I need it to be high enough that one new customer can pay back CAC quickly, and low enough that the market still pulls us forward without heroic sales efforts.

2) Channel strategy: where to invest next

ASP by acquisition channel often reveals uncomfortable truths:

- Partner referrals may be fewer but much higher ASP.

- Paid search may bring volume but low ASP and high churn.

- Outbound may raise ASP but require strong qualification.

This is where segmentation matters more than the headline number. If a channel has lower ASP but dramatically better retention and expansion, it can still be the best channel.

Pair ASP with:

- CAC by channel

- NRR (Net Revenue Retention) by segment (if you can)

- Logo Churn trends to ensure low-ASP cohorts aren't leaking

3) Sales hiring and comp: set the floor

A simple sales-led sanity check:

- If your fully-loaded cost per rep is high, you need enough ASP (and enough win volume) to justify headcount.

- If ASP is below the threshold, you either need to raise prices, move upmarket, improve conversion, or shift to a more product-led motion.

Even if you're not modeling every variable, ASP provides the "deal size floor" for hiring plans.

4) Product roadmap: what to build to earn higher ASP

Raising ASP sustainably usually comes from shipping value that changes willingness to pay:

- Features that unlock larger teams (SSO, audit logs, admin controls)

- Workflows that become "system of record," not a nice-to-have

- Usage-based value that scales with customer outcomes

If your ASP rises only through discounts tightening, you may still be under-monetizing the product.

Blended ASP can rise without a price change if more bookings come from higher tiers; this is usually a packaging and targeting story.

When ASP lies (and how to fix it)

ASP is easy to compute and easy to misinterpret. These are the common failure modes.

Mixing MRR and annual deals

If you include annual-prepay customers in a "new MRR per customer" calculation without normalizing, ASP will swing based on billing cadence, not product value.

Fix:

- Normalize annual contracts into monthly equivalents (or compute on ACV).

- Keep one definition as your primary, and show the other as a supporting view.

Counting expansions as "new sales"

If expansions are included in numerator but not reflected in the denominator, ASP becomes inflated and unstable.

Fix:

- Create separate ASPs: new customer ASP and expansion ASP.

- Use Expansion MRR and Contraction MRR for post-sale motion, not ASP.

Hidden one-time charges

Onboarding fees and implementation services can make ASP look healthier than recurring reality.

Fix:

- Report "recurring ASP" and "total first invoice ASP" separately.

- If you sell meaningful services, track them intentionally—don't let them distort subscription decisions.

Small sample size volatility

A single enterprise deal can double ASP in a month when volume is low.

Fix:

- Use a trailing average (for example a trailing 3-month average) and segment the data.

- Report median deal size alongside ASP when deal sizes are lumpy.

Interpreting ASP changes with a simple decomposition

When ASP changes, you want to know whether it's due to:

- Price realization (less discounting, higher list price)

- Plan/seat/usage selection (customers buying more)

- Customer mix (different segments buying)

A practical way to decompose is to compute ASP by segment and then compare the blended result month to month.

Conceptually:

You're looking for which term moved:

- Segment ASP moved (pricing/discounting/product value)

- Segment share moved (targeting/channel/mix)

This prevents the most common mistake: celebrating "higher ASP" when you simply lost your small-customer funnel.

Benchmarks and target ranges

Benchmarks depend heavily on market, category, and GTM. Still, founders benefit from rough ranges to sanity-check whether the business model matches the motion.

| GTM model | Typical ASP unit | Directional ASP range | What "too low" usually breaks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-serve / PLG | New MRR per new customer | $20–$200+ | Paid acquisition and support become uneconomic |

| SMB sales-assist | ACV per deal | $1k–$10k | Inside sales time can't be justified |

| Mid-market sales-led | ACV per deal | $10k–$50k | Rep productivity, payback, and hiring plan |

| Enterprise | ACV per deal | $50k–$250k+ | Long cycles and procurement overhead dominate |

These are not goals. They're "does this make sense?" guardrails. The right target is the ASP that supports:

- Your CAC and payback expectations

- Your retention reality (MRR Churn Rate and Net MRR Churn Rate)

- Your customer success capacity

The Founder's perspective

I set an ASP target as a constraint: given CAC and payback, what deal size do we need? Then we decide whether to raise price, change packaging, or change who we sell to—because the math won't negotiate.

How to operationalize ASP in weekly review

If you want ASP to drive action, review it the same way each week/month:

- Pick one primary ASP definition (new MRR per new customer for PLG; ACV per deal for sales-led).

- Split by segment and channel (at minimum).

- Track discount rate alongside net ASP.

- Pair with volume (new customers / closed-won count) so you see tradeoffs.

- Tie to unit economics: CAC, payback, and retention.

In GrowPanel, ASP is most useful when you can slice it with consistent filters (segment, plan, timeframe) and compare it to other revenue metrics. See ASP and Filters for how teams typically break it down.

Discounting can depress net ASP across every segment; the key is whether discounts are strategic (to win large, retainable accounts) or compensating for weak value capture.

Quick rules founders can rely on

- Rising ASP is good only if retention and payback hold. Otherwise it's a short-term win masking long-term damage.

- Falling ASP is not automatically bad. If it comes with lower CAC, faster cycles, and strong retention, it can be the start of efficient scale.

- ASP should be segmented by design. A single blended number is a headline, not a diagnosis.

- Don't let billing mechanics distort the story. Normalize annual vs monthly and keep recurring separate from one-time fees.

Bottom line

ASP is a leverage metric. It tells you—quickly—whether your pricing and go-to-market are producing enough revenue density per deal to fund growth. Define it consistently, segment it aggressively, and interpret it alongside CAC, payback, and retention. When ASP moves, treat it like a signal to investigate mix, packaging, and discount behavior—not as a vanity win or loss.

Frequently asked questions

There is no universal good ASP; it depends on your go-to-market model and buyer. Self-serve products often win with lower ASP and higher volume, while sales-led teams need higher ASP to cover sales costs. Judge ASP against CAC, payback period, and your ability to retain and expand.

Use the unit that matches how you sell and forecast. If customers buy monthly subscriptions, use new MRR per new customer. If you sell annual contracts, use ACV per closed-won deal. The key is consistency: pick one primary definition, document it, and keep comparisons apples to apples.

Higher ASP can be driven by mix shift toward larger customers, price increases, fewer discounts, or fewer low-tier signups. Any of these can reduce logo volume. The right interpretation is whether the higher ASP improves LTV:CAC and payback without hurting retention or shrinking your addressable market.

For decision-making, ASP should usually reflect net price after discounts, because that is what you actually collect and what funds CAC payback. Track gross list-price ASP separately if you need to monitor discounting behavior. If discounting rises, verify it is tied to larger deals or better retention.

Use ASP by plan, segment, and channel to see which offers create healthy revenue density. If ASP rises mainly from discounting discipline, focus on sales enablement and approvals. If ASP rises from customers buying higher tiers, invest in onboarding, activation, and paywalls that move customers into paid value.