Table of contents

ACV (annual contract value)

Founders care about ACV because it quietly dictates your entire growth machine: how many deals you need, what pipeline coverage is "enough," what kind of sales motion you can afford, and whether moving upmarket is improving the business or just slowing it down.

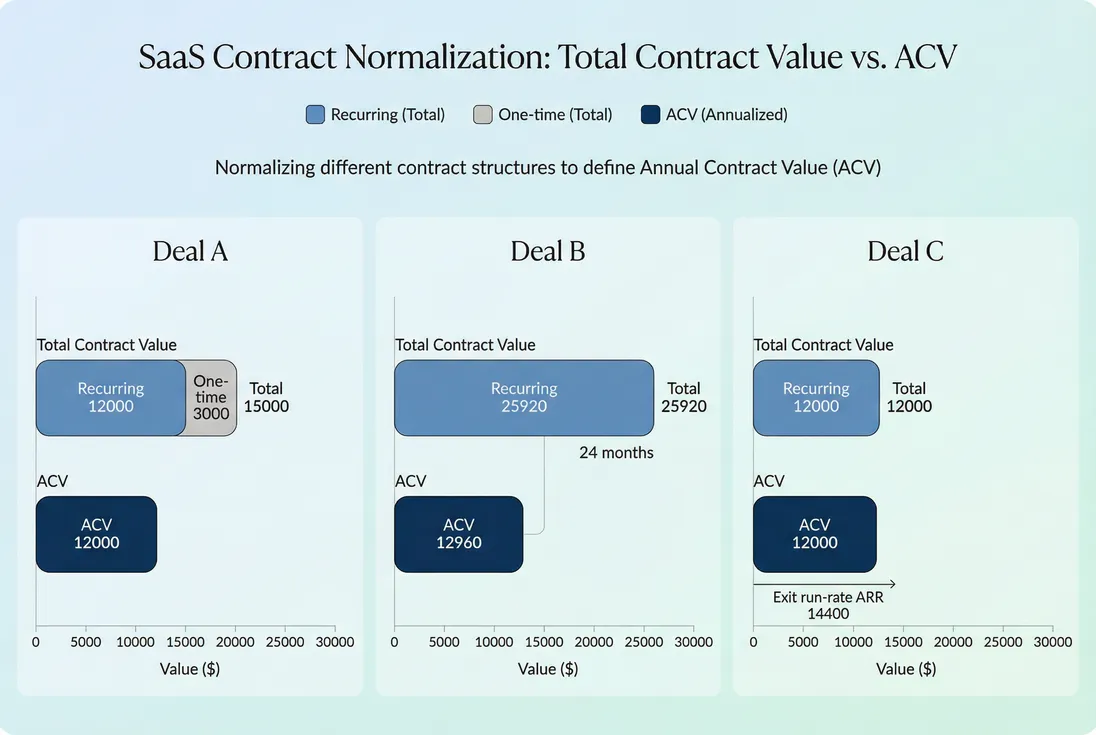

ACV (annual contract value) is the annualized recurring value of a customer contract, typically measured net of discounts and excluding one-time fees. It turns different contract structures (monthly vs annual, one-year vs multi-year, ramp deals) into a single comparable yearly number.

What ACV is for

ACV is most useful when you're making sales and go-to-market decisions and you need a deal size metric that behaves consistently across contract terms.

Use ACV to answer questions like:

- "If we want $1.2M of new recurring revenue next year, how many deals do we need at today's deal size?"

- "Did our average deal size increase because of pricing, or because we're closing bigger customers?"

- "Are we discounting more to win enterprise, and is it worth the longer cycle?"

ACV complements (but doesn't replace) company-level revenue metrics like MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue) and ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue). Think of it like this:

- MRR/ARR tell you what the business is worth right now as a run rate.

- ACV tells you what your new and renewing contracts are worth on an annual basis.

The Founder's perspective

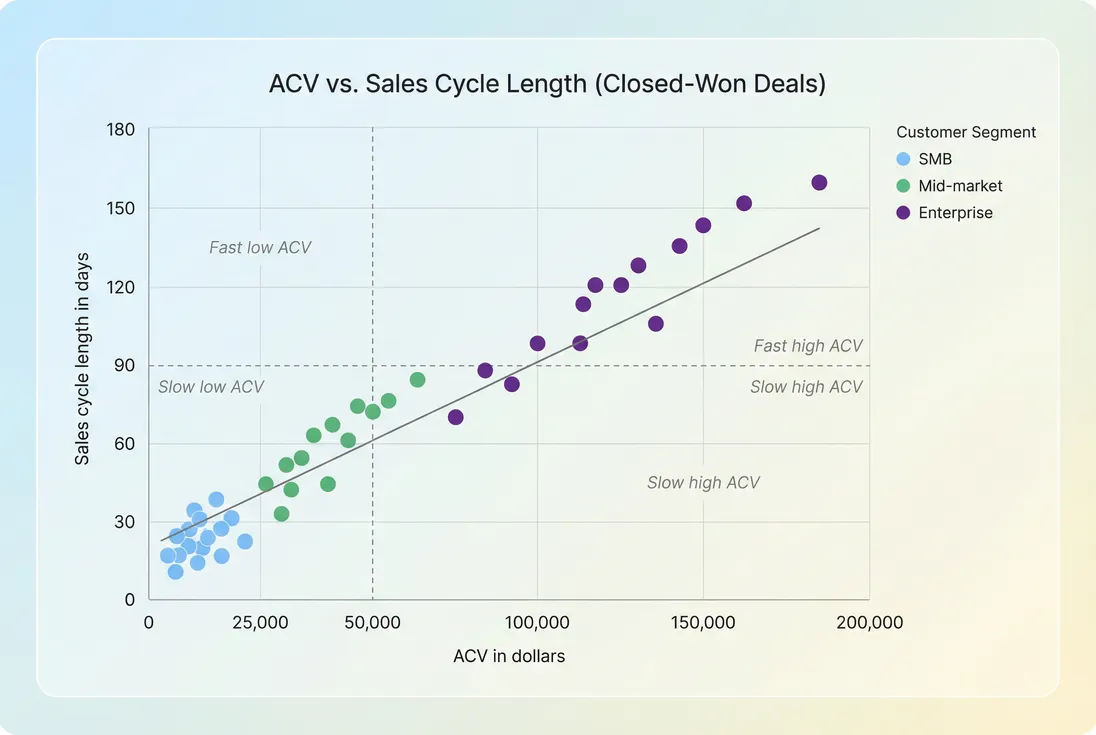

If you're debating whether to hire two more AEs, ACV is one of the fastest sanity checks. Higher ACV can support a higher CAC and longer sales cycle; low ACV usually demands a lower-cost motion (product-led, inbound-heavy, tighter automation).

How to calculate ACV cleanly

The cleanest definition for most SaaS businesses:

- Include: contracted recurring subscription fees (net of recurring discounts)

- Exclude: one-time setup, implementation, training, usage overages that are not committed, taxes, payment processing fees

At its simplest, ACV is the annualized version of contracted recurring value:

Common shortcuts (and when they work)

If a deal is a straightforward monthly subscription with a stable run rate, teams often annualize MRR:

That's fine when:

- pricing is steady through the year, and

- the customer is actually committed (not truly month-to-month churnable).

For month-to-month plans with high early churn risk, annualizing can overstate reality. In those cases, be explicit in naming:

- Run-rate ACV (annualized current MRR)

- Contracted ACV (what the customer is actually committed to)

Multi-year contracts

Multi-year deals are where ACV prevents a lot of self-inflicted confusion.

Example: a 2-year contract at $2,000/month with no changes.

- Total contracted recurring value = $2,000 × 24 = $48,000

- Contract length = 2 years

- ACV = $24,000

This keeps your "average deal size" comparable even as you sell longer terms.

Ramp deals (step-ups)

Ramp pricing is common in mid-market and enterprise: a customer starts smaller, then grows.

You have two valid ways to compute ACV—pick one based on how you run the business and use it consistently:

Average-in-year ACV (revenue realism)

Annualize the total recurring billed in the first 12 months.Exit run-rate ACV (capacity planning)

Use the month-12 run rate annualized, which better reflects where the account ends up.

The danger is mixing these approaches across deals; it makes trend lines meaningless.

One-time fees and services

Setup fees can be meaningful cash, but they should not inflate recurring economics. Track them separately with One Time Payments and keep ACV recurring-only.

If your business bundles mandatory implementation into the subscription price, that's still recurring and belongs in ACV. If it's a separate invoice, it usually doesn't.

ACV makes different contract structures comparable by annualizing recurring commitment and excluding one-time fees.

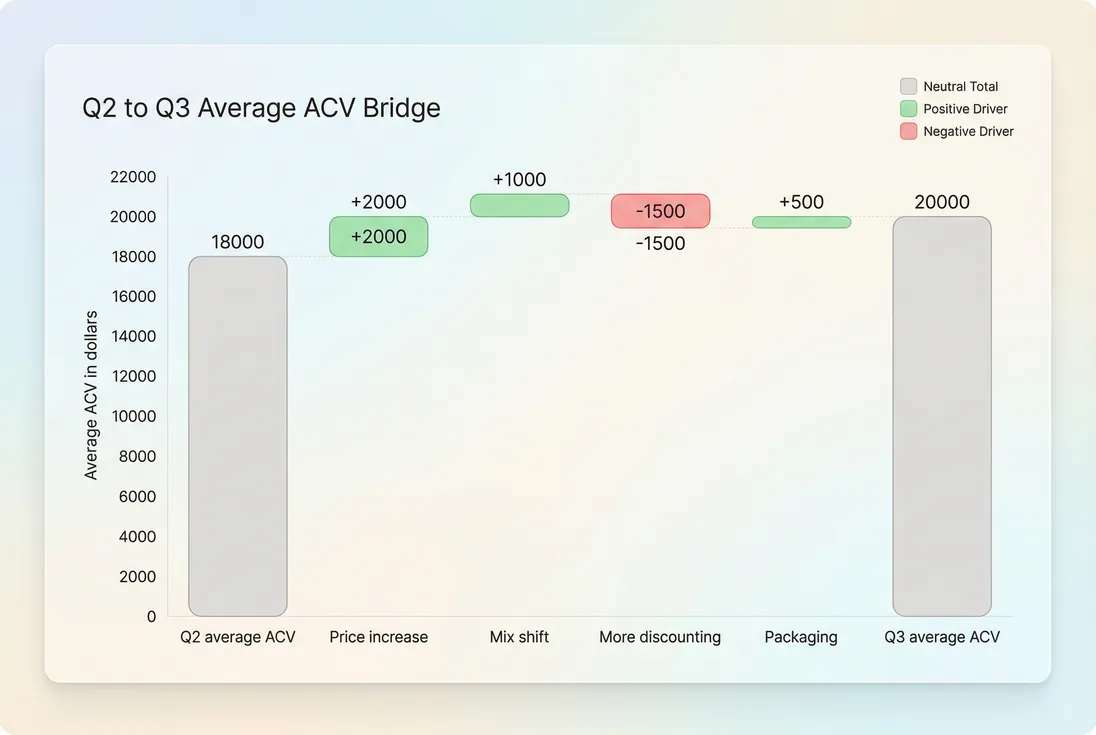

What pushes ACV up or down

If ACV changes, it's almost always one (or more) of these drivers. The trick is to identify which driver changed, because each implies a different decision.

Pricing and packaging changes

- List price increases raise ACV if they stick.

- Packaging (bundles, feature gating) can raise ACV without changing list price by moving customers to higher tiers.

- Watch for hidden tradeoffs: higher ACV with lower activation or worse retention is not a win.

Related reading: ASP (Average Selling Price) and ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account).

Discounting and concessions

Discounts reduce ACV. But founders often miss the second-order effects:

- Discounts can increase win rate (good).

- Discounts can also attract lower-fit customers (bad).

- Discounts tied to longer terms can make ACV look stable while cash collection improves, masking weaker pricing power.

If you want ACV to be decision-useful, define it as net recurring (after discounts), and treat changes in discounting as a first-class driver. See: Discounts in SaaS.

Customer mix shift

ACV rising can simply mean you're landing larger customers.

That's not automatically good or bad; it changes the operating model:

- higher ACV typically means longer Sales Cycle Length and more implementation

- potentially higher retention, but also more whale risk (one account matters a lot)

Use mix-aware views:

- median ACV (less sensitive to outliers)

- ACV by segment (SMB vs mid-market vs enterprise)

- ACV by channel (PLG vs outbound)

To manage the risk side, pair ACV trends with Customer Concentration Risk and Cohort Whale Risk.

Contract length and billing terms

Contract length is a common source of confusion:

- Moving customers from monthly billing to annual prepay often does not change ACV if the annual price is the same.

- It does change cash flow, Deferred Revenue, and collections behavior (see Accounts Receivable (AR) Aging).

ACV is not a cash metric. Don't use it to forecast runway.

Usage-based components

If you have Usage-Based Pricing or Metered Revenue, ACV depends on whether usage is committed.

Practical approach:

- Include committed minimums in ACV.

- Exclude volatile overages from ACV, and track them separately (or as an "expected usage" scenario).

The Founder's perspective

If your ACV trend depends on assumed usage, you don't have a stable deal-size metric—you have a forecast. That's fine, but label it that way and keep a second, contract-only ACV for capacity planning and compensation.

How founders use ACV in planning

ACV becomes powerful when you use it to convert strategy into concrete operating targets.

1) Turning growth targets into deal counts

If your plan calls for a certain amount of new recurring revenue (annualized), the back-of-the-envelope deal math is:

Example:

- Target: $1,200,000 of new annualized recurring revenue

- Average ACV: $24,000

- Deals needed: 50

Now you can stress-test the plan:

- Are 50 wins feasible at your current win rate?

- Do you have enough pipeline volume?

- Do you have enough AE capacity given your cycle length?

Tie-ins: Win Rate, Qualified Pipeline, and Sales Rep Productivity.

2) Pipeline coverage that matches your ACV

Higher ACV usually means:

- fewer total deals

- higher variance (one deal can swing the quarter)

- more concentrated pipeline risk

Founders should respond by:

- tracking pipeline coverage by segment

- requiring deeper deal qualification for large ACV opportunities

- forecasting with scenarios, not a single number

3) Unit economics and payback expectations

ACV affects what you can afford to spend to acquire a customer, but only through retention and margin.

Use ACV alongside:

Practical interpretation:

- If ACV is rising and payback is improving, you likely have real pricing power or better-fit customers.

- If ACV is rising but payback is worsening, you may be buying growth with discounts, higher sales cost, or longer ramp.

4) Interpreting ACV with retention

ACV alone can trick you into celebrating the wrong thing. Pair it with retention metrics:

- NRR (Net Revenue Retention) to see if larger customers expand or shrink after landing.

- GRR (Gross Revenue Retention) to see if you're losing revenue via churn and downgrades.

- Logo Churn to see if your customer count is durable.

If ACV rises because you're moving upmarket, you should expect:

- lower logo churn (often, not always)

- higher NRR (if the product supports expansion)

- more volatile quarter-to-quarter bookings

What a "good" ACV looks like

There is no universal benchmark that applies across categories. But founders still need some calibration. Here are common ranges by motion (very approximate):

| Segment / motion | Typical ACV range | What it implies operationally |

|---|---|---|

| Self-serve SMB | $500–$5,000 | Low-touch onboarding, high volume, strong product-led motion |

| Sales-assist SMB | $3,000–$15,000 | Lightweight AE/SDR, fast cycle, careful CAC control |

| Mid-market | $10,000–$50,000 | Dedicated AEs, clearer ICP, more structured implementation |

| Enterprise | $50,000–$250,000+ | Longer cycles, procurement, security reviews, higher concentration risk |

How to benchmark yourself without fooling yourself:

- Use median ACV and 75th percentile, not just average.

- Break it down by channel and segment.

- Review ACV together with cycle length and win rate.

A simple ACV bridge forces you to explain what actually changed—pricing, mix, or discounting—so you can take the right action.

Where ACV misleads (and how to fix it)

ACV is easy to compute and easy to misuse. These are the failure modes that show up most often in founder dashboards and board decks.

Mixing bookings, cash, and revenue recognition

- ACV is a normalized contract value metric.

- Cash collected depends on billing terms, payment timing, and collections.

- Recognized revenue follows accounting rules (see Recognized Revenue).

If you sell annual prepay, ACV can be flat while cash spikes and deferred revenue grows. That's not a contradiction—it's three different concepts.

Inflating ACV with non-recurring items

If you include implementation or one-time fees, you'll:

- overestimate pipeline quality,

- overpay commissions (if comp is tied to ACV),

- misread whether pricing changes are working.

Keep ACV recurring-only and track one-time revenue separately.

Ignoring refunds, chargebacks, and taxes

When you calculate net values, don't let operational leakage distort the signal:

These aren't "ACV drivers," but if you're using invoiced amounts as inputs, they can pollute the number.

Getting fooled by outliers

A single enterprise deal can swing average ACV by 20–50% in a low-volume quarter.

Fixes:

- report median and average

- add ACV by segment

- track customer concentration as ACV rises

Treating rising ACV as pure improvement

ACV going up is only "better" if the rest of the system holds.

If ACV increases and you also see:

- declining win rate,

- longer sales cycles,

- worse CAC payback,

- higher Burn Multiple,

then you may be moving upmarket in a way that hurts capital efficiency.

As ACV rises, sales cycles often lengthen; plan headcount, pipeline coverage, and cash accordingly.

Practical takeaways

- Define ACV once (what's included, excluded, and how you handle ramp and usage) and keep it consistent.

- Use ACV to translate growth goals into deal counts and pipeline requirements, then sanity-check against win rate and cycle length.

- Interpret ACV changes via drivers: pricing, packaging, discounting, mix, and term length—not just the headline trend.

- Pair ACV with retention and concentration metrics so "bigger deals" don't become "bigger risk" in disguise.

Frequently asked questions

ACV is a deal-level annualized value of a single contract. ARR is a company-level annualized run rate across all recurring subscriptions, and MRR is the monthly run rate. A one year deal often has ACV equal to ARR added, but multi-year terms, ramp pricing, and one-time fees can make them diverge.

Usually no. Most SaaS teams define ACV as recurring subscription value only, excluding one-time onboarding, implementation, and professional services. Including them inflates deal size, breaks comparability across contracts, and can lead you to over-hire sales or overestimate payback. Track one-time revenue separately and keep your ACV definition consistent.

It depends on your go to market motion and buyer. Self-serve SMB products often land in the low thousands per year, mid-market commonly ranges from ten to fifty thousand, and enterprise can be fifty thousand to several hundred thousand plus. Use your own distribution and sales cycle as the real benchmark, not industry averages.

Not always. Higher ACV can mean pricing power and better unit economics, but it can also signal heavier discounting tied to longer terms, more customer concentration risk, or a shift to larger buyers with longer sales cycles. Validate the change by segment, gross margin, win rate, and retention to ensure you are improving quality, not just deal optics.

Normalize them by annualizing the recurring commitment: total contracted recurring value divided by contract length in years. This makes a two year contract comparable to a one year contract. Separately track total contract value and cash timing because those drive financing and working capital, but they should not distort ACV trend analysis.