Table of contents

SQL (sales qualified lead)

Founders don't miss targets because they lack "leads." They miss because their team spends time on the wrong conversations, then wonders why pipeline coverage looks fine but cash doesn't show up. SQL is the metric that tells you whether your go-to-market machine is producing sales conversations that can realistically become revenue.

An SQL (sales qualified lead) is a lead that has been vetted by sales (or by a sales-owned process) and confirmed as worth active sales effort now—because it matches your ICP and shows credible buying intent, with a clear next step.

This article is about the SaaS meaning of SQL (not the database language).

What an SQL should mean

An SQL is not "someone who booked a meeting." It's "someone we would rationally invest sales time in, because they have a plausible path to becoming a customer."

A practical SQL definition usually includes three ingredients:

- Fit: company and persona match your ICP (industry, size, tech stack, geography, compliance requirements).

- Intent: signals they may buy (pain acknowledged, active evaluation, usage signal, budget owner involvement, urgency).

- Next step: mutual agreement on what happens next (discovery, technical evaluation, security review, proposal).

Where teams go wrong is turning SQL into a vanity counter—either too strict (starving sales) or too loose (flooding sales with low-quality work).

SQL vs MQL (and why founders care)

If you track MQLs, SQL is the "sales reality check" on marketing volume. MQL is usually marketing-owned qualification; SQL is sales-owned validation.

If you want the upstream view, read MQL (Marketing Qualified Lead). If you want the downstream view, SQL should connect cleanly to Qualified Pipeline and then to Win Rate.

A workable SQL definition by motion

Different motions need different SQL rules. Here's a simple way to make it explicit:

| Sales motion | What typically becomes an SQL | Common mistake |

|---|---|---|

| Inbound demo (SLG) | Demo request from ICP + validated use case + correct buyer persona | Treating every demo request as SQL |

| SDR outbound | Positive reply from ICP + pain confirmed + discovery scheduled | Counting "polite replies" as SQL |

| PLG-assisted sales | Product usage shows value + account matches ICP + outreach accepted | Promoting usage-only signals without buying intent |

| Enterprise | Multi-stakeholder account fit + project confirmed + timeline known | Creating SQLs from vague "curiosity" meetings |

The Founder's perspective: If your SQL definition isn't written down and enforced, your forecast is built on sand. A strict, consistent SQL definition is how you prevent "pipeline theater" from driving hiring, spend, and runway decisions.

How to calculate SQL metrics

SQL is a stage, but founders need rates and unit economics, not just counts. Track SQL in a consistent time window (weekly for ops, monthly for planning).

Core calculations

1) SQL count

How many leads became SQLs in a period.

2) Lead-to-SQL rate (from all leads)

3) MQL-to-SQL rate (if you use MQL)

4) SQL-to-opportunity rate (definition varies)

5) Cost per SQL (for paid channels or blended CAC modeling)

Cost per SQL becomes much more actionable when paired with CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost) and CAC Payback Period. A low cost per SQL is meaningless if those SQLs don't convert downstream.

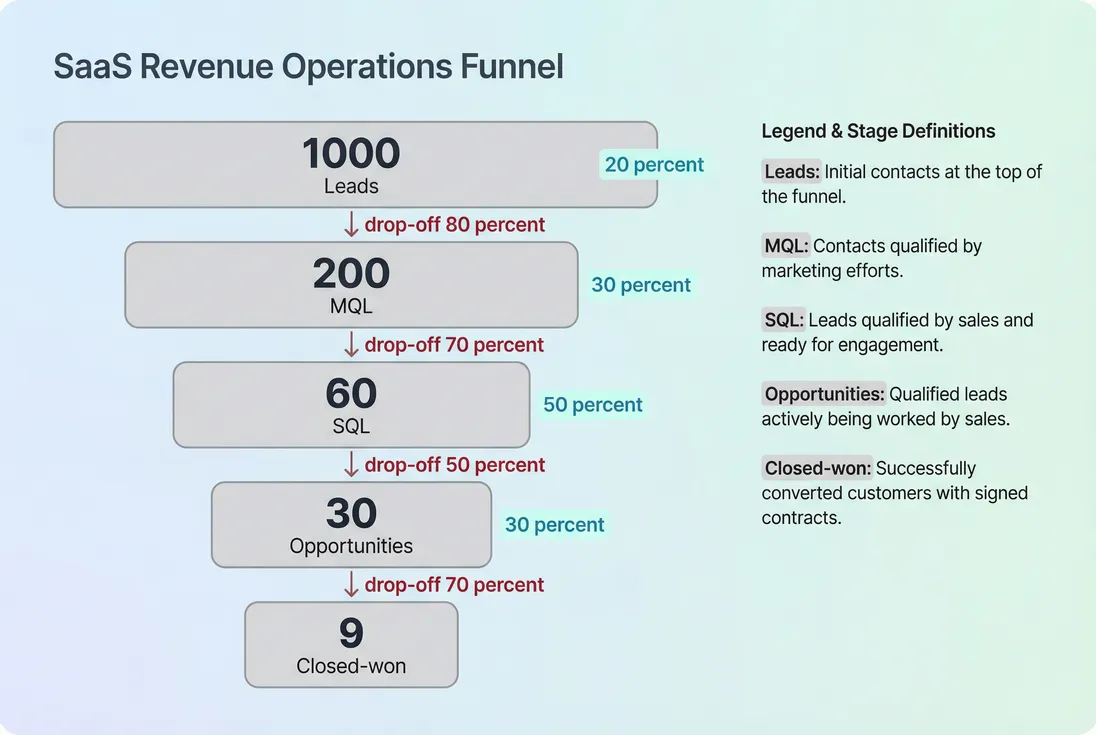

A funnel example (why rates matter)

If last month you had:

- 1,000 leads

- 200 MQLs

- 60 SQLs

- 30 opportunities

- 9 closed-won deals

Then:

- Lead-to-SQL = 6%

- MQL-to-SQL = 30%

- SQL-to-opportunity = 50%

- Opportunity win rate = 30% (9 of 30)

That last number is why SQL is dangerous as a standalone KPI: you can "grow SQLs" while quietly destroying win rate and stretching your Average Sales Cycle Length.

What drives SQL volume and quality

SQL is the output of multiple systems working together: targeting, messaging, routing, qualification, and follow-up speed. When SQL trends move, don't ask "what happened?" Ask "which lever changed?"

The biggest levers

1) ICP clarity (fit quality)

If your ICP is vague, SQL becomes subjective. Tightening ICP often reduces SQL volume initially, then improves win rate and sales cycle length. Use a simple fit rubric (must-have firmographics + disqualifiers) and enforce it.

2) Intent signal strength

Intent is usually the difference between "interested" and "buying." Strong intent signals include:

- a defined problem with business impact

- active evaluation (timeline, alternatives, internal sponsor)

- product usage that correlates with retention and expansion

If you're PLG, connect SQL promotion to usage behaviors and activation milestones. See Feature Adoption Rate and Time to Value (TTV).

3) Speed-to-lead and follow-up quality

Many teams lose SQLs before qualification because response time is slow or initial outreach is generic. Faster follow-up can increase SQL conversion without changing spend.

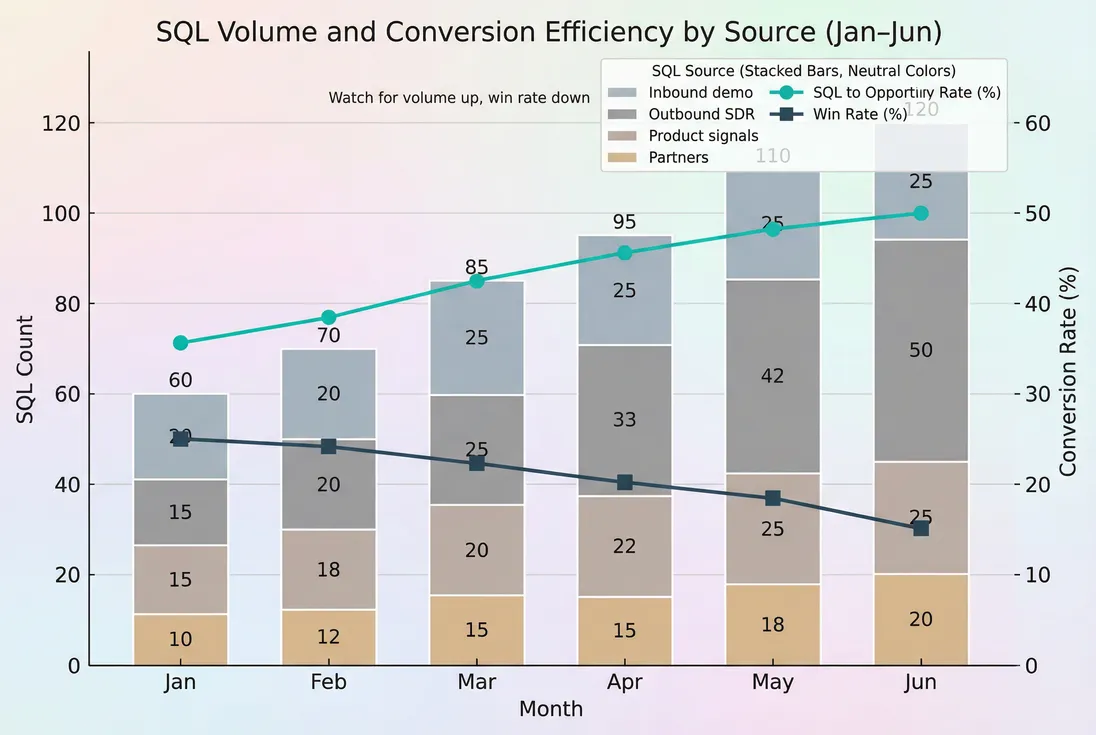

4) Channel mix

Outbound, paid search, partnerships, and product signals can all produce SQLs—but with very different downstream conversion. If your SQL count jumps after you add a new channel, assume quality changed until proven otherwise.

5) Rep incentives and definitions

If reps are compensated on SQLs, you'll get more SQLs. If they're compensated on pipeline created, you may get bloated opportunities. Align incentives with outcomes and enforce stage criteria with regular audits.

Segment SQLs by source and outcome

A founder-friendly way to manage SQL quality is to segment SQLs by source and track downstream performance: SQL-to-opportunity, win rate, and time-to-close.

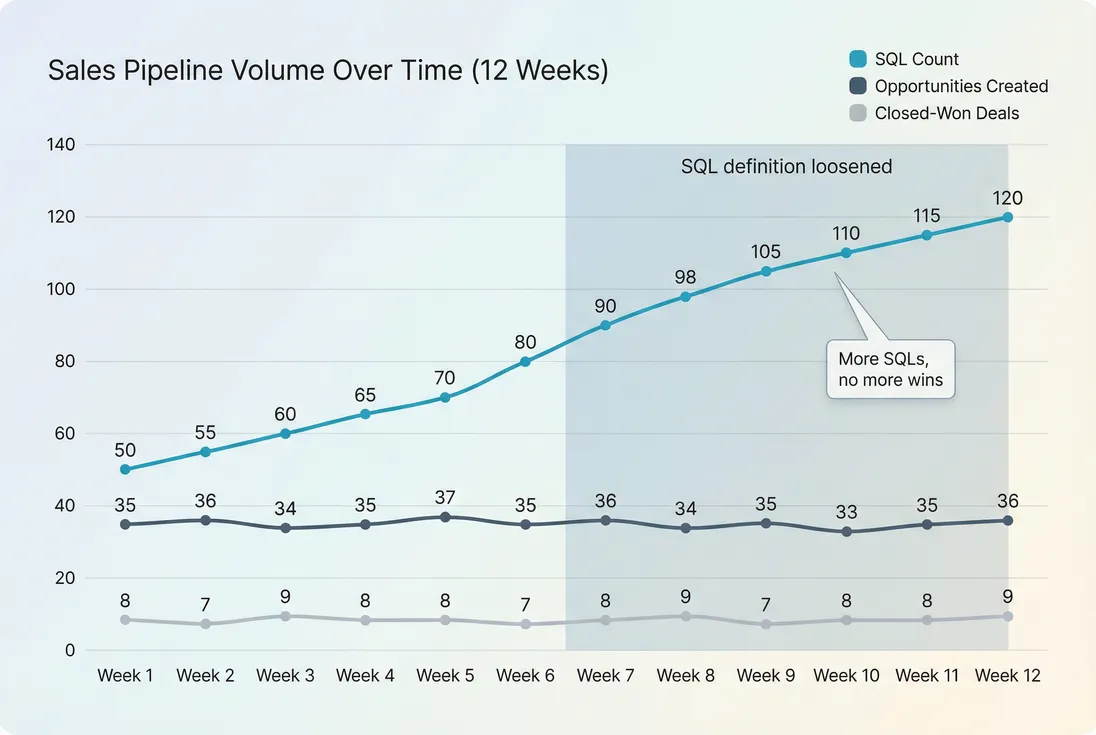

How to interpret changes in SQL

SQL is an operational metric. Interpretation should be mechanical: follow the chain from SQL to pipeline to revenue.

Four common patterns (and what they mean)

| What changed | Likely meaning | What to check next |

|---|---|---|

| SQLs up, win rate down | Definition loosened or channel mix worsened | SQL-to-opportunity rate, stage notes quality, disqual reasons |

| SQLs down, win rate up | Qualification tightened, fewer but better leads | Pipeline coverage risk, rep capacity, top-of-funnel volume |

| SQLs flat, opportunities down | Sales is rejecting SQLs or delaying opp creation | Acceptance criteria, routing, follow-up speed |

| SQLs up, sales cycle longer | More complex deals or weaker intent | Persona shift, pricing/packaging friction, POC requirements |

The key is to treat SQL as a leading indicator, not an achievement.

The Founder's perspective: I don't want "more SQLs." I want the minimum SQLs required to hit the number with confidence. When SQL volume rises, I immediately ask whether my team just got busier or whether we actually improved conversion to pipeline and cash.

A quick diagnostic checklist

When SQL trends move materially (say 20%+ week-over-week), review:

- Definition drift: did you change required fields, meeting rules, or routing?

- Rejection reasons: why did sales mark leads as not qualified?

- Downstream conversion: SQL-to-opportunity and Win Rate

- Deal size mix: shifts in ACV (Annual Contract Value) and ASP (Average Selling Price)

- Sales capacity: are you responding slower due to workload?

When SQL breaks

SQL becomes misleading when it turns into a proxy for "activity." Here are the failure modes that usually hit SaaS teams right as they start hiring and spending more.

SQL inflation

Symptoms:

- SQL count rises

- AEs complain about lead quality

- Opportunity volume rises but bookings don't

- CAC worsens

Root causes:

- "SQL" includes anyone who accepts a meeting

- SDRs optimize for meetings instead of qualified progress

- Marketing starts passing low-intent leads to hit targets

Fix:

- Tighten the SQL checklist (fit + intent + next step)

- Require a short qualification note or required fields

- Track SQL-to-opportunity and win rate by source

SQL starvation

Symptoms:

- Reps aren't busy

- Pipeline coverage drops

- You miss targets despite strong product and pricing

Root causes:

- Overly strict qualification before any sales conversation

- Routing delays or unworked leads

- A narrow ICP with insufficient top-of-funnel

Fix:

- Loosen early exploration while keeping SQL strict (separate "sales accepted" from "sales qualified" if needed)

- Improve speed-to-lead

- Expand ICP cautiously and measure downstream

Definition mismatch across teams

Symptoms:

- Marketing celebrates SQL growth; sales says "none are real"

- Forecast variance increases

- Board-level debates about lead quality replace diagnosis

Fix:

- Publish the SQL definition and examples

- Review a sample of SQLs weekly across marketing + sales

- Use one system of record for stage changes

How founders use SQL to make decisions

SQL is most useful when you use it to answer operational questions: how much pipeline you can expect, where to invest, and when to hire.

1) Backsolve SQL needed for targets

Start with the revenue target and work backward:

- Decide your bookings target (often tied to ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue))

- Convert to deals using ACV

- Convert deals to opportunities using win rate

- Convert opportunities to SQLs using SQL-to-opportunity rate

A compact way to express this:

Example:

- Target: 200,000 in new ARR this quarter

- ACV: 20,000 → 10 deals

- Win rate: 25% → 40 opportunities

- SQL-to-opportunity: 50% → 80 SQLs

Now you have a concrete debate: "Can our current motion generate 80 real SQLs next quarter at acceptable cost and quality?"

2) Decide whether to hire SDRs or AEs

SQL helps you size capacity:

- If AEs have low meeting volume and low pipeline creation, you may need more SQL supply (SDRs, marketing, partnerships).

- If AEs are overloaded and SQL response time is slow, you may need more AE capacity—or stricter SQL criteria to protect time.

Pair SQL review with Sales Rep Productivity and Sales Efficiency.

3) Optimize spend without guessing

If paid spend increases SQLs but lowers win rate, you may be buying the wrong intent. If spend decreases SQLs but win rate holds, you might be cutting too deep. Use SQL by source as the "first gate," then confirm with pipeline and CAC outcomes.

This is where SQL connects to unit economics:

- CPL (Cost Per Lead) tells you what you pay for volume

- SQL rates tell you how much of that volume is usable

- CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost) tells you whether the motion pays back

4) Improve qualification and handoff

If you can't clearly explain why someone is an SQL, you can't improve it. A lightweight operating rhythm that works:

- Weekly: review 10 random SQLs with sales + marketing

- Monthly: update SQL definition and disqualifiers based on win/loss and rejection reasons

- Quarterly: revisit ICP and pricing/packaging effects (SQL quality often changes after pricing moves; see Discounts in SaaS if discounting is part of qualification)

The Founder's perspective: The job isn't to argue about whether marketing or sales is "right." The job is to make the SQL threshold so clear that both teams can predict downstream conversion. When that happens, forecasts stabilize, hiring gets easier, and CAC becomes controllable.

Practical takeaways

If you only do five things with SQL:

- Write a strict SQL definition: fit + intent + next step.

- Track SQL-to-opportunity and win rate alongside SQL count.

- Segment SQLs by source and monitor downstream conversion by segment.

- Backsolve SQLs needed from ARR targets and conversion rates.

- Audit SQL quality regularly to prevent definition drift.

SQL is not a trophy. It's an early-warning system for whether your go-to-market is producing conversations that can turn into durable revenue.

Frequently asked questions

It depends on what you measure SQL against. From MQL to SQL, 20 to 40 percent is common when targeting a clear ICP with strong intent signals. From raw leads to SQL, 2 to 10 percent is typical. The key is stability and strong downstream win rate, not a single benchmark.

Usually SQL quality dropped or the definition loosened. Check SQL to opportunity conversion, win rate, and average sales cycle length. If those worsened while SQL count rose, you created more sales work without more pipeline. Also check channel mix changes and whether reps are marking meetings as SQL too early.

Only if your sales team would act on them as true sales-ready opportunities. Many teams track PQLs separately, then promote to SQL when firmographic fit and buying intent are confirmed and a next step is set. If you label PQLs as SQLs immediately, you risk inflating pipeline forecasts and misallocating reps.

Work backward from bookings. Convert ARR target to required deals using ACV, then divide by win rate to get opportunities needed, then divide by SQL to opportunity conversion to get SQLs needed. This creates a capacity plan for SDRs and AEs and makes marketing spend decisions concrete.

An SQL is a lead confirmed as a good sales conversation, typically with ICP fit and validated intent. An opportunity is a deal record in your CRM with a defined sales process, stage progression, and forecast value. Some teams create an opportunity at SQL; others only after discovery. Consistency matters more than the label.