Table of contents

SOM (serviceable obtainable market)

Founders rarely fail because their product is "bad." More often, they fail because the winnable market is smaller than their burn, or slower to access than their runway. SOM is the metric that prevents you from building a plan that only works in a spreadsheet.

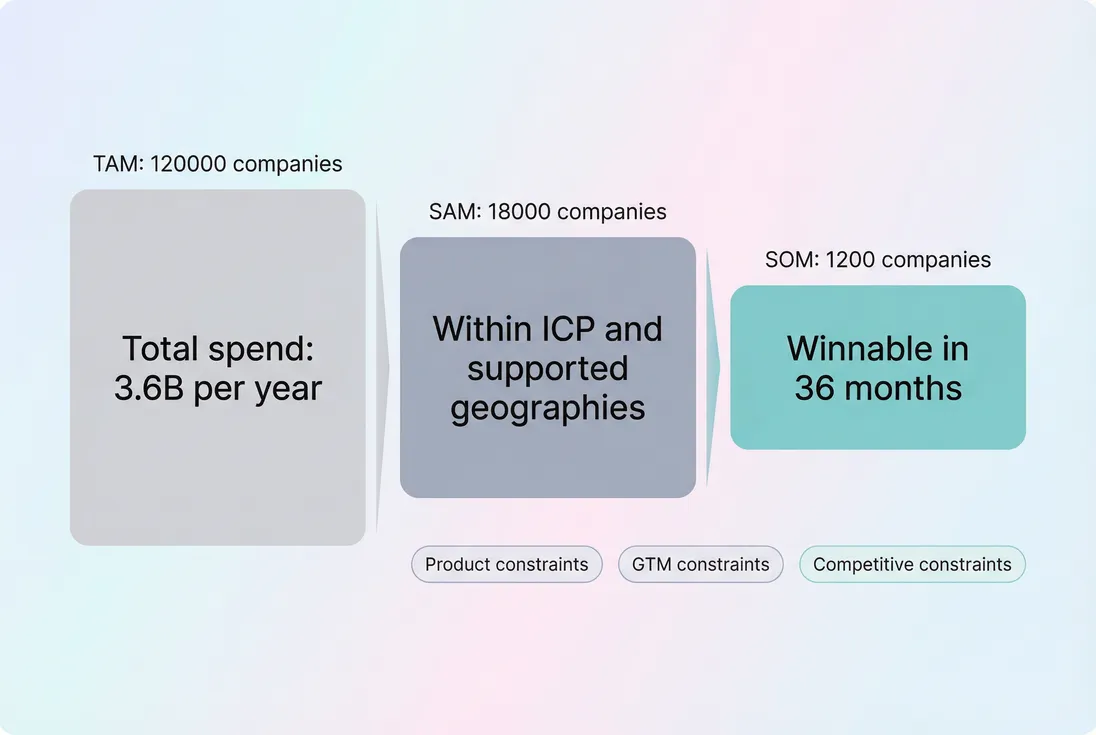

SOM (serviceable obtainable market) is the portion of your SAM (serviceable addressable market) that you can realistically capture over a defined timeframe, given your go-to-market motion, competition, budget, and execution constraints.

If TAM and SAM are about possibility, SOM is about probability.

Where SOM fits in decisions

SOM is not a vanity market number. It's a planning constraint that should directly shape:

- Your ARR target realism (and whether the business can be venture-scale or should be bootstrapped)

- Your ICP boundaries (who you must exclude to win faster)

- Your pricing strategy (whether you need higher ARPA or more volume)

- Your channel strategy (whether your current acquisition motion can supply enough pipeline)

- Your hiring plan (sales capacity and customer success load)

If you haven't already defined TAM and SAM, it's worth reading TAM (Total Addressable Market) and SAM (Serviceable Addressable Market) first. SOM depends on both, but forces you to operationalize them.

The Founder's perspective

If your SOM can't support your ARR goal without assuming heroic win rates or unlimited sales capacity, your "growth plan" is actually a request for more time and money. SOM turns that into an explicit tradeoff: change ICP, change pricing, change channels, or change the target.

How big can we realistically win?

Most founders should estimate SOM using a bottom-up model, then sanity-check it against a top-down share-of-SAM view.

The simplest SOM formula (revenue)

At its simplest, SOM is:

This is easy to say, but hard to justify. "Achievable share" hides the real work: reachability, conversion rates, capacity, and retention.

A bottom-up SOM formula (accounts)

A practical bottom-up model starts with countable accounts in your ICP:

Then convert customers into recurring revenue using ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account) or ACV:

Where "months per year" is 12 if ARPA is monthly.

Capacity-constrained SOM (often the real limiter)

Even with strong demand, your SOM may be capped by how many opportunities your team can handle:

Sales capacity is usually a function of:

- number of reps

- deals a rep can actively run per month

- Sales Cycle Length

- onboarding and implementation bandwidth (for enterprise)

This is why founders who "found a big market" still stall: they sized demand, not throughput.

Top-down vs bottom-up vs capacity-based

| Method | What it's good for | Where it breaks | When to use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Top-down (share of SAM) | Quick sanity check | Hides GTM mechanics | Early narrative, investor context |

| Bottom-up (accounts and conversion) | Connects to pipeline and ARR | Requires real assumptions | Planning, headcount, targets |

| Capacity-based (throughput) | Prevents impossible plans | Underestimates latent demand | Sales-led motions, services-heavy onboarding |

What inputs actually move SOM?

SOM is not a single knob. It's the result of several business levers. The key is knowing which ones you can change in 30–90 days vs 6–18 months.

1) ICP definition and segmentation

Changing your ICP changes both the count and the winnability of accounts.

A narrower ICP often increases SOM in the near term because:

- targeting is sharper

- messaging is clearer

- competition is more avoidable

- win rate rises

- sales cycles shorten

A broader ICP often increases SAM but can decrease SOM because your team becomes less effective.

Practical founder move: define 2–3 subsegments and estimate separate SOMs. Then pick the one with the best path to repeatable wins.

2) ARPA and packaging

SOM in ARR is highly sensitive to pricing and packaging.

If you raise ARPA, your SOM ARR can rise without increasing account penetration—but only if:

- you can still close at that price (win rate doesn't collapse)

- your retention holds (see NRR (Net Revenue Retention) and GRR (Gross Revenue Retention))

- discounting doesn't quietly undo it (see Discounts in SaaS)

This is why you should model SOM in both customers and ARR.

The Founder's perspective

If your SOM requires winning thousands of tiny accounts, you're committing to a high-volume machine (support, self-serve onboarding, low CAC). If your SOM requires winning dozens of large accounts, you're committing to a high-touch machine (long cycles, high proof requirements, higher CAC). Neither is "better," but each demands different execution.

3) Channel reachability

"Reachable rate" is the share of your target accounts you can consistently put into a selling motion.

Examples:

- Outbound: reachable rate is constrained by list quality, deliverability, rep activity, and brand trust.

- Paid: reachable rate is constrained by intent density and CAC inflation.

- Partnerships: reachable rate is constrained by partner incentives and enablement.

This connects directly to Qualified Pipeline, Win Rate, and CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost).

If your plan assumes a reachable rate you've never demonstrated, your SOM is aspirational, not obtainable.

4) Win rate and sales cycle

Win rate and cycle length are multiplicative constraints: small improvements compound.

Example: if you improve win rate from 15% to 22% while also reducing cycle length from 90 days to 60 days, you don't just close more—you also increase the number of cycles you can run per year, which increases throughput.

This is why SOM belongs in the same conversation as:

5) Retention and expansion (SOM vs "land and expand")

SOM is often treated as a new-logo concept, but for SaaS the obtainable market in ARR depends on retention and expansion.

If expansion is a meaningful growth driver, your SOM model should separate:

- "obtainable logos"

- "obtainable ARR per logo over time" (expansion curve)

This is where understanding Expansion MRR and Contraction MRR matters, because a segment with modest logo SOM may still have large ARR SOM if expansion is strong.

A worked example founders can copy

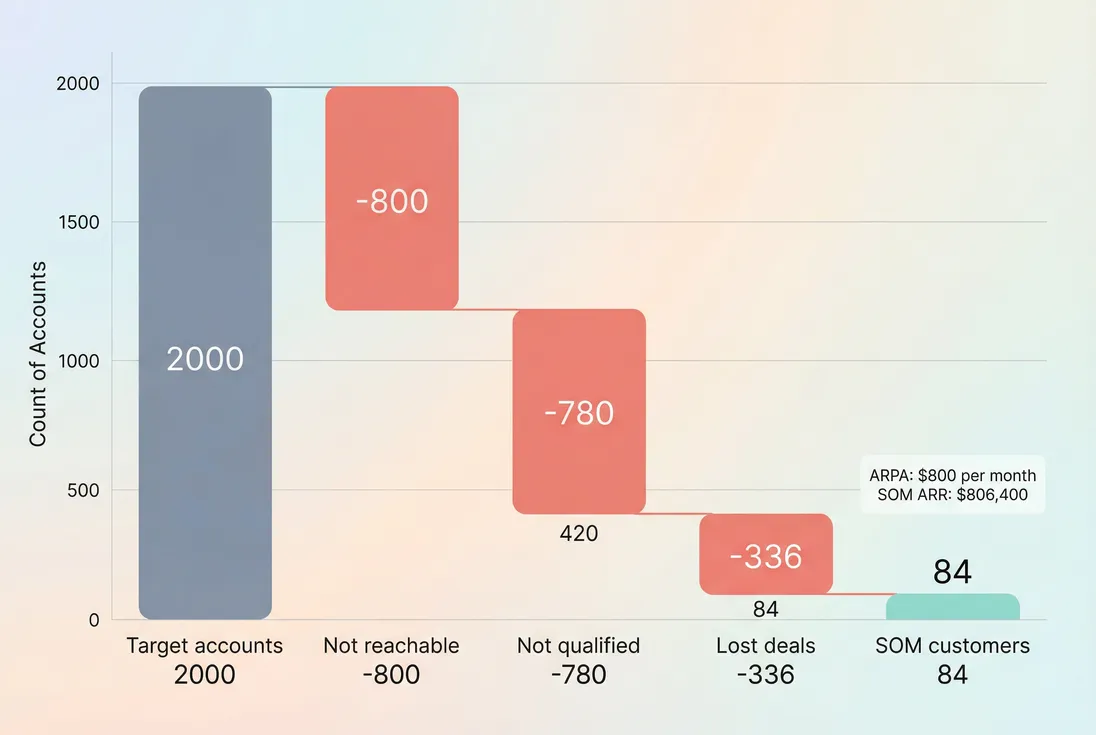

Assume you sell to 2,000 target accounts (defined by industry + company size + geography). You're modeling a 36-month window.

Inputs (initial assumptions):

- Reachable rate: 60% (you can reliably get 1,200 into a real buying conversation or trial)

- Qualified rate: 35% (420 are a true fit with active need)

- Win rate: 20% (84 customers)

- ARPA: $800 per month

Customers:

ARR:

So in this segment and timeframe, your SOM is about 84 customers or $806k ARR.

Now the decision question becomes concrete: is $806k ARR enough to justify your burn, hiring, and roadmap? If not, what changes the output?

How founders use SOM in planning

SOM becomes useful when it directly informs choices you can execute this quarter.

Use SOM to set an ARR target you can explain

A strong plan ties ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue) goals to a believable SOM path:

- target segment count

- pipeline coverage requirement

- win rate and sales cycle assumptions

- expected ARPA

- retention and expansion expectations

If you can't explain your ARR target as a conversion of SOM inputs, you're effectively guessing.

Use SOM to choose between pricing and volume

Two ways to "double SOM ARR":

- Increase obtainable customers (better reach, qualification, win rate, new channel)

- Increase obtainable ARR per customer (pricing/packaging, expansion)

The second is often faster to test, but easier to break with churn or discounting. Track downstream retention impacts with Customer Churn Rate and Logo Churn.

Use SOM to pressure-test CAC and payback

SOM should constrain your acceptable CAC. If your obtainable segment only supports a limited number of wins, you can't afford a CAC that requires huge scale to amortize.

Connect the dots:

- SOM determines realistic new-customer volume

- volume + CAC determines spend

- spend vs gross margin determines runway and efficiency (see Burn Rate and Burn Multiple)

Use SOM to decide if you need a new segment

A common anti-pattern: you miss targets and respond by "going upmarket" or "adding SMB."

SOM helps you decide if that's strategy or panic:

- If the segment's SOM is large but you're not capturing it, the issue is usually execution (messaging, channel, product gaps).

- If the segment's SOM is genuinely small relative to your plan, you need a new segment, a new motion, or a different business model.

The Founder's perspective

SOM answers a painful question: are we underperforming in a big opportunity, or performing fine in a small one? The fix is completely different. One is a GTM and product iteration problem; the other is a market selection problem.

When SOM breaks (common mistakes)

Mistake 1: Confusing "interested" with "reachable"

Website traffic and "signups" are not reachability. Reachability means you can reliably create qualified conversations at a predictable cost.

If you're PLG, reachability is tied to activation and conversion (see Conversion Rate and Product-Led Growth). If you're sales-led, it's tied to outbound effectiveness and pipeline creation (see Sales-Led Growth).

Mistake 2: Using a generic market share number

"1% of a billion-dollar market" is not a plan. The market doesn't distribute itself evenly, and incumbents don't sit still.

Replace generic share with:

- account counts in the ICP

- competitive displacement difficulty

- time-to-value and proof requirements

- procurement friction

Mistake 3: Ignoring time horizon

SOM must include a timeframe. "Obtainable eventually" is not obtainable within your runway.

A useful SOM statement looks like:

- "We can win 150 customers in mid-market logistics in 36 months" not

- "There are 50,000 logistics companies."

Mistake 4: Not modeling churn

If your SOM is in ARR, churn changes the amount of new ARR you must add just to hit the target.

If you expect meaningful churn, pair your SOM model with retention expectations using Retention and MRR Churn Rate.

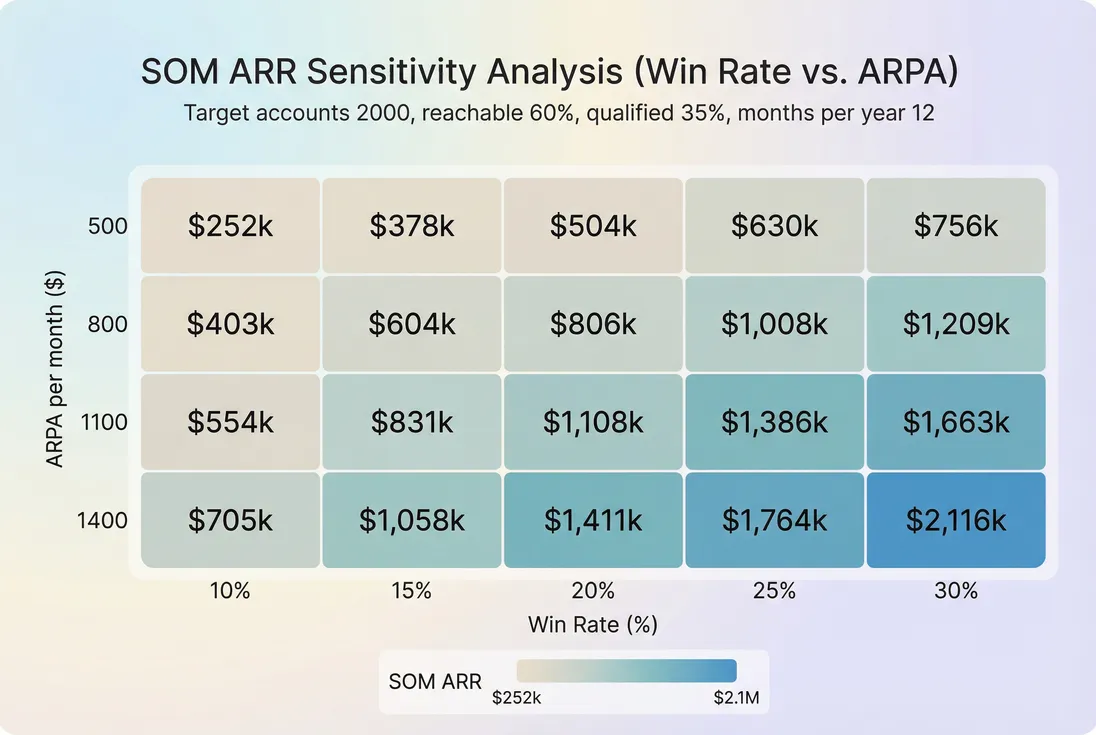

How to make SOM actionable (a simple sensitivity check)

Because SOM is driven by assumptions, founders should run a sensitivity table on the two inputs they can most influence near-term. For many teams, that's win rate and ARPA.

This makes your next 90 days much clearer:

- If a modest ARPA increase fixes the model, prioritize packaging and pricing tests.

- If only a huge win-rate jump fixes it, you likely need a sharper ICP, better proof, or a different channel.

- If nothing fixes it, the segment is too small (or too hard) for your goals.

How to interpret SOM changes over time

SOM isn't a KPI you "track weekly," but it should change when reality changes.

SOM tends to increase when:

- you narrow ICP and win faster

- you find a repeatable channel (reachability rises)

- your product becomes easier to adopt (qualification and win rate rise)

- you add credible proof (case studies, security, integrations)

- expansion becomes reliable (ARR per logo rises)

SOM tends to decrease when:

- competition intensifies in your core segment

- CAC rises faster than LTV (see LTV (Customer Lifetime Value) and LTV:CAC Ratio)

- your sales cycle lengthens (procurement, security reviews)

- churn rises in the segment (meaning the "obtainable ARR" is lower)

The point isn't to defend your original SOM number. The point is to keep your plan anchored to what's winnable now.

A practical SOM checklist

Before you finalize SOM for planning or fundraising, be able to answer:

- Who exactly is in the segment? (clear firmographic and use-case boundaries)

- How many are there? (countable, not a vague estimate)

- How do they buy? (self-serve vs sales-led; procurement friction)

- What is your observed win rate and cycle length? (or a justified proxy)

- What ARPA is realistic after discounts? (see ASP (Average Selling Price))

- What capacity constraints apply? (sales, onboarding, support)

- What churn and expansion do you expect in this segment?

If you can't answer these, you don't have SOM—you have a hope.

Frequently asked questions

TAM is everyone who could ever buy in theory, SAM is the portion you can actually serve with your product and constraints, and SOM is what you can realistically win in a defined time window. SOM is where pricing, sales capacity, win rate, and competition show up in the math.

There is no universal benchmark, but early-stage SaaS plans often assume low single-digit penetration of the SAM over three to five years unless there is a clear wedge and distribution advantage. If your model needs double-digit share quickly to work, it usually signals pricing, targeting, or channel risk.

Start with customers or accounts to ensure the segment is real and countable, then convert to ARR using ARPA or ACV. Using ARR makes tradeoffs visible: you can reach the same SOM with fewer higher-value customers or many lower-value ones, with very different CAC and support implications.

Compare your assumed win rate, sales cycle length, and ARPA to observed results in your current segment. Back into how many qualified opportunities you would need and whether your current lead sources can produce them. If the implied pipeline is unrealistic, your SOM is overstated.

Update SOM when your ICP changes, pricing changes materially, a new channel becomes repeatable, or the competitive landscape shifts. As a rule, revisit quarterly for planning, and immediately after major GTM changes. Treat SOM as a living constraint, not a one-time slide for fundraising.