Table of contents

Sales rep productivity

Sales rep productivity is the difference between "we hired and grew" and "we hired and got more expensive." If it's rising, you can scale ARR with confidence. If it's falling, headcount becomes a burn accelerant and your forecasts get fragile fast.

Definition (plain English): sales rep productivity is the amount of revenue outcome your sales team produces per quota-carrying rep in a defined period—typically new ARR booked per rep per month or quarter, sometimes expressed as new MRR.

What exactly should you measure?

Most founders ask for "rep productivity" but mean one of three different things. Pick the one that matches the decision you're making.

Common productivity definitions

- New logo productivity (most common): new ARR from new customers per quota-carrying rep.

- Total bookings productivity: new ARR from new logos plus expansions, per rep.

- Gross profit productivity: gross profit from bookings per rep (useful when COGS varies by deal size).

In subscription businesses, it's cleanest to express outcomes in ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue) terms so you can compare across billing cadences. If you're earlier-stage and live in monthly pricing, MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue) works too—just be consistent.

Internal context that often matters:

- Use booked contract value for sales productivity (sales controls bookings).

- Use recognized revenue for accounting productivity (sales does not control timing).

If you want to connect productivity to pricing, pair it with ASP (Average Selling Price) and discount policy (see Discounts in SaaS). If you want to connect it to efficiency and burn, pair it with CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost), CAC Payback Period, and Burn Multiple.

How to calculate it (without fooling yourself)

At its simplest:

The two places teams quietly introduce error are (1) the rep denominator and (2) the revenue numerator.

Get the rep denominator right

If reps join mid-month (or you have churn), "end of month headcount" will mislead you. Use an average based on time in seat:

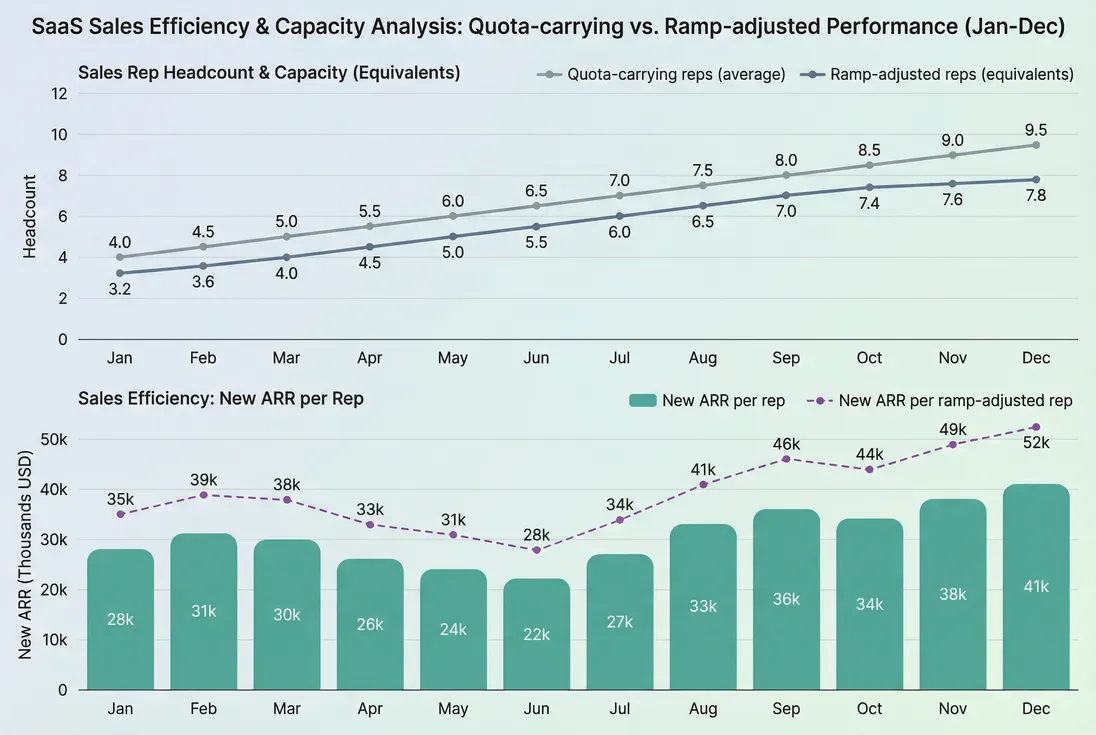

Even better: use ramp-adjusted rep equivalents so hiring doesn't look like a performance collapse.

Ramp weighting is a simple factor by tenure, for example:

- Month 1: 0.25

- Month 2: 0.50

- Month 3: 0.75

- Month 4+: 1.00

This turns "how many people do we have?" into "how much selling capacity do we have?"

The Founder's perspective: If you don't ramp-adjust, you'll blame the team for a math artifact. That leads to the two classic mistakes: cutting enablement because "reps aren't producing," or over-hiring because "we just need more at-bats."

Define the numerator so it matches accountability

Decide what counts as "produced":

- New ARR closed-won (standard for AEs).

- New ARR started (can be distorted by implementation delays).

- New ARR collected (useful in high-risk collections environments; see Accounts Receivable (AR) Aging).

Also decide if you include:

- Upsells (see Expansion MRR and Contraction MRR concepts to keep it honest)

- Reactivations (see Reactivation MRR)

- One-time fees (usually excluded from "rep productivity" unless your GTM sells a lot of non-recurring)

The key is consistency. A "better" definition that changes every quarter is worse than a "good enough" definition you can trend.

What this metric reveals (and what it doesn't)

Sales rep productivity is a capacity metric. It answers: How much revenue can we produce with the sales capacity we have? That makes it directly useful for planning and for debugging growth stalls.

It reveals

- Whether adding headcount is likely to add ARR or just add cost.

- Whether your pipeline generation is keeping up with team size.

- Whether you have a segmentation problem (same reps, different outcomes by segment).

- Whether pricing / packaging changes improved monetization (often visible as ASP shifts).

It does not reveal (by itself)

- Whether the revenue will stick (you still need GRR (Gross Revenue Retention) and NRR (Net Revenue Retention)).

- Whether growth is efficient (pair with Sales Efficiency and CAC Payback Period).

- Whether your funnel is healthy (you need leading indicators like pipeline created, meetings, win rate, and sales cycle).

A useful mental model is to treat rep productivity as the "output," then use funnel metrics to explain "why."

What drives productivity up or down

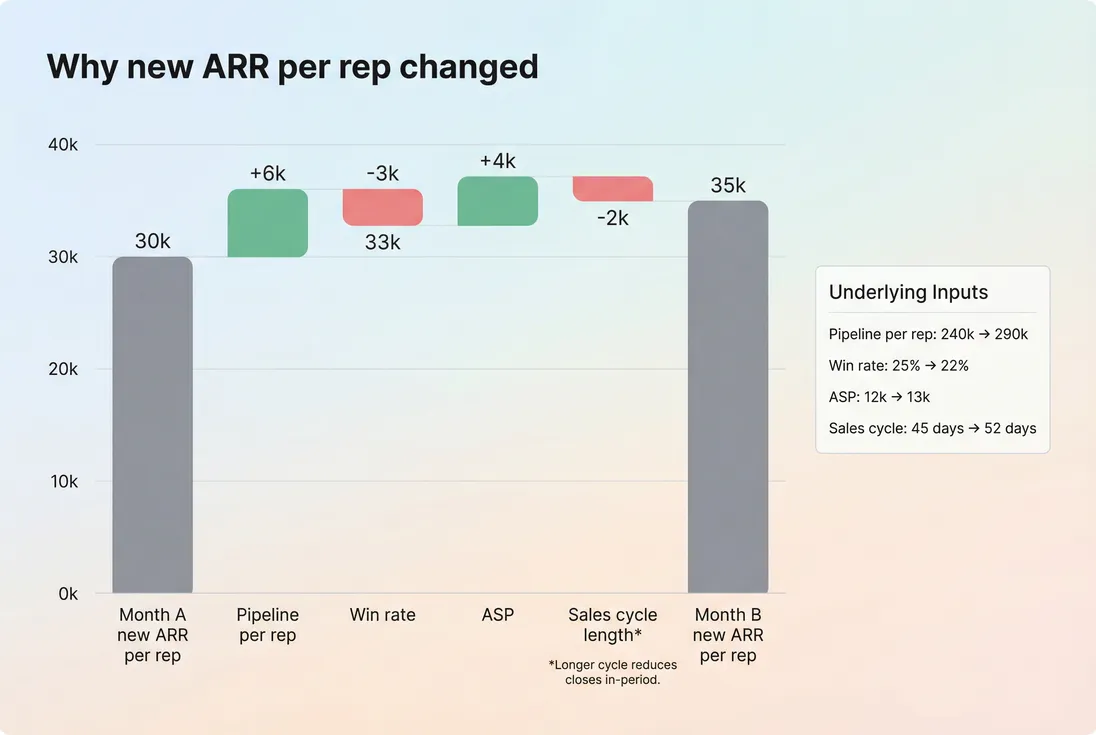

You can decompose productivity into a few controllable levers. One practical version:

If your motion is cycle-time sensitive, time is the hidden denominator. Over a fixed quarter, longer cycles reduce what a rep can close:

This is why productivity can fall even when "win rate looks fine"—cycle length expanded, or opportunities got stuck.

Typical drivers, in plain operational terms:

- Pipeline created per rep: Are reps generating/receiving enough qualified pipeline? (See Qualified Pipeline and Lead Velocity Rate (LVR) for upstream pressure.)

- Win rate: Are you winning enough of what you touch? (See Win Rate.)

- Sales cycle length: How quickly can you turn pipeline into bookings? (See Sales Cycle Length.)

- ASP and discounting: Are you selling bigger deals, or just discounting harder? (See ASP (Average Selling Price) and Discounts in SaaS.)

- Territory and segment mix: Did you shift reps into smaller accounts or harder verticals?

- Ramp and enablement: Is performance changing, or is the team simply less tenured?

How to diagnose a change in productivity

When founders see a dip, they usually ask: Is this a rep problem, a demand problem, or a math problem? Here's a fast way to answer.

Step 1: Remove ramp dilution

Plot productivity two ways:

- per raw average rep

- per ramp-adjusted rep

If raw productivity drops but ramp-adjusted holds, you likely have a capacity transition, not a performance collapse. Your job becomes ensuring enough pipeline exists for the added capacity.

Step 2: Split by segment and motion

A single blended number hides a lot. Break productivity into:

- SMB vs mid-market vs enterprise (often proxied by ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account) bands)

- inbound-led vs outbound-led (if you can tag it)

- new logo vs expansion

If enterprise productivity "fell," it may just be a mix shift toward smaller ACV or earlier-stage pipeline.

Step 3: Decompose into levers

Use a "bridge" view: starting productivity, then the contribution from pipeline, win rate, ASP, and cycle length.

This decomposition is how you avoid the unhelpful conclusion: "reps need to work harder."

The Founder's perspective: Productivity is not a motivational slogan; it's an operating system. When it drops, your first job is attribution—otherwise you'll ‘fix' the wrong lever (and burn a quarter proving it).

What "good" looks like (practical benchmarks)

There is no universal benchmark because productivity is largely a function of ACV, cycle length, and how much pipeline is inbound. Still, founders need ranges for planning.

Rule-of-thumb planning ranges (fully ramped AE)

Use these as order-of-magnitude planning targets, not performance grades:

| Motion | Typical ACV | Common annual new ARR per fully ramped AE |

|---|---|---|

| SMB / transactional | 3k–20k | 500k–1.2m |

| Mid-market | 20k–80k | 1.0m–2.0m |

| Enterprise | 80k+ | 1.5m–3.0m+ |

Where teams get into trouble is applying enterprise targets to SMB (too high) or SMB targets to enterprise (too low), then misdiagnosing the issue as rep quality.

A more useful internal benchmark: trend stability

For most early-stage SaaS, the most actionable "benchmark" is whether productivity is:

- stable or rising as you add reps (healthy scaling), or

- declining with headcount growth (pipeline constraint, pricing pressure, or ramp overload)

If productivity is flat but your cost per rep is rising (higher OTE, more tools, more enablement overhead), efficiency can still be deteriorating. That's when you connect productivity to SaaS Magic Number and Burn Multiple.

How founders use it for hiring plans

Rep productivity turns "we want to grow ARR" into a capacity plan.

Capacity planning equation

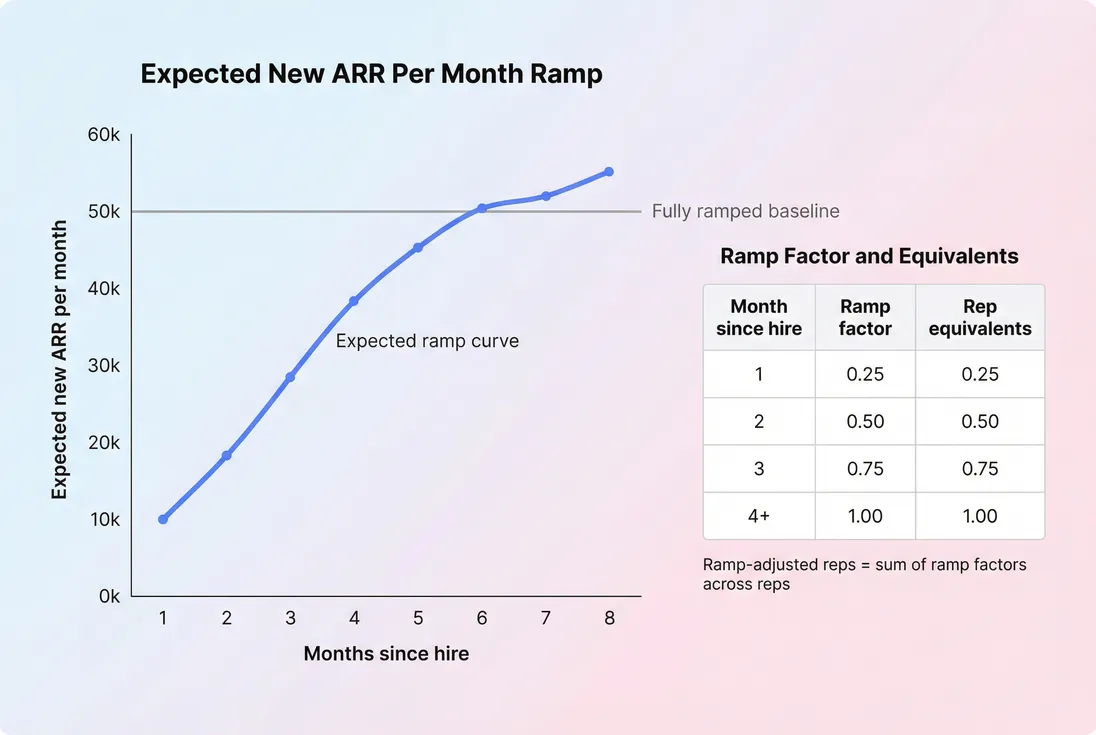

Then adjust for ramp:

- If it takes 4 months to ramp, hiring in Q2 contributes less to Q2 and more to Q3/Q4.

- Your hiring plan must be timed to your sales cycle. A 90-day cycle means Q4 bookings require Q3 pipeline.

Simple example

- Target: 3.6m new ARR next year

- Expected productivity: 1.2m new ARR per fully ramped AE annually

You need ~3 fully ramped AEs worth of capacity:

But if half your year is spent ramping new hires, you might need 4–5 hires depending on start dates and ramp curve.

Sanity-check with pipeline coverage

Even if the math says "hire 3 AEs," you can't hire into a pipeline deficit. If pipeline created per rep is falling as headcount grows, the constraint is often upstream (marketing, SDR capacity, targeting, positioning).

That's why productivity belongs in the same weekly view as:

- Qualified Pipeline

- Win Rate

- Sales Cycle Length

- ASP (Average Selling Price)

When productivity "breaks" (common failure modes)

1) Pipeline doesn't scale with headcount

Symptom: productivity declines right after adding reps; reps complain about lead quality and empty calendars.

Fix:

- Invest in pipeline creation capacity (SDRs, partners, inbound engine).

- Tighten ICP targeting so effort isn't diluted.

- Track pipeline created per rep as a first-class metric.

2) Discounting props up bookings

Symptom: productivity looks fine, but ASP drops, payback worsens, and churn rises later.

Fix:

- Audit discounts by segment and rep tenure.

- Tie approvals to deal quality and expected retention (connect to Logo Churn and NRR (Net Revenue Retention)).

3) Cycle length expands quietly

Symptom: pipeline is "up," but bookings lag; forecasts slip.

Fix:

- Break the cycle into stages and identify where deals stall.

- Improve qualification (fewer zombie opps).

- Revisit buyer enablement (security, procurement, legal).

4) You changed the mix

Symptom: productivity dips after moving upmarket or adding a new vertical.

Fix:

- Treat it as a deliberate investment period; separate "new segment reps" from "core segment reps."

- Adjust expectations and ramp. Don't demand core productivity from a new motion in one quarter.

How to improve productivity (without burning the team)

Most improvements come from system changes, not heroics.

Improve input quality (pipeline)

- Narrow ICP to raise win rate and shorten cycles.

- Increase meeting-to-opportunity conversion (better discovery, clearer qualification).

- Fix handoffs (marketing to SDR to AE), because friction kills throughput.

Improve conversion (win rate)

- Message clarity: fewer "nice to have" deals.

- Competitive positioning: reps need a crisp reason you win.

- Deal review discipline: coach on late-stage objections, pricing, procurement.

If you're not already tracking win rate consistently, start with Win Rate and define it the same way across the team.

Improve monetization (ASP)

- Packaging: push value-based tiers instead of bespoke discounts.

- Multi-year incentives: careful—can inflate bookings but change cash dynamics and expectations.

- Expansion path: ensure the product supports natural growth (seat expansion, add-ons, usage-based scaling; see Usage-Based Pricing).

Improve throughput (cycle length)

- Reduce steps that don't change the buying decision.

- Preempt security/procurement blockers earlier.

- Use clear mutual action plans (MAPs conceptually; see MAP as a planning artifact, not a UI requirement).

The Founder's perspective: The fastest sustainable productivity gains usually come from shorter cycles and higher ASP, not from squeezing more calls per day. If your "improvement plan" is just activity pressure, you'll get short-term bookings and long-term churn.

A practical ramp model (so you can stop arguing)

Ramping is where productivity debates go to die—unless you make it explicit.

If you write this ramp model down and use it in forecasting, three things get easier:

- hiring timing

- quota setting

- diagnosing whether a rep is truly underperforming or just early

How this connects to the rest of your metrics

Sales rep productivity is not a standalone score. It's a node in a causal chain:

- Higher productivity can improve Burn Rate and Burn Multiple (same ARR growth with less spend).

- If achieved via discounting, it can hurt CAC Payback Period and long-term LTV (Customer Lifetime Value).

- If achieved via better targeting and value delivery, it can improve downstream NRR (Net Revenue Retention) and reduce Logo Churn.

A disciplined founder reads productivity alongside:

- ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue) growth targets

- Sales Efficiency

- Win Rate

- Sales Cycle Length

- ASP (Average Selling Price)

- retention metrics (GRR (Gross Revenue Retention) / NRR (Net Revenue Retention))

That combination tells you whether you're scaling a healthy go-to-market motion—or just scaling activity.

Frequently asked questions

Use a revenue outcome tied to your GTM motion, then divide by a clean rep denominator. Most teams use new ARR booked per quota-carrying rep per month (or per quarter). For expansion-focused teams, track expansion ARR per rep separately. Keep the definition stable for trend comparisons.

Benchmarks vary widely by ACV, sales cycle, and inbound versus outbound mix. As a rough planning range, early SMB AEs often land around 500k to 1.2m new ARR per fully ramped rep annually, mid-market closer to 1m to 2m, and enterprise can exceed 2m with long cycles. Use your own ramp and win rate.

Averages get diluted by ramping reps. If you add headcount faster than pipeline creation scales, the numerator lags while the denominator jumps. Separate fully ramped reps from ramping reps using ramp-adjusted rep equivalents, and watch leading indicators like pipeline created per rep, meetings booked, and sales cycle length.

Include it only if the same reps are responsible for expansions and you want a single capacity metric. Otherwise, split new logo productivity from expansion productivity so you do not hide a new logo shortfall behind renewals or upsells. This also aligns incentives and staffing decisions across sales and customer success.

Start with your ARR growth target, then back into the bookings you need after considering churn and expansions. Divide required new ARR by expected productivity per fully ramped rep, then add a ramp buffer. Sanity-check with pipeline coverage and sales cycle timing so you do not hire into a pipeline deficit.