Table of contents

Sales cycle length

Sales cycle length is one of the cleanest "speed of cash" signals in a sales-led SaaS business. When it stretches, your forecasts get shakier, your hiring plan gets riskier, and your payback math degrades—even if your product and win rate look fine.

Definition (plain English): sales cycle length is the time it takes a deal to go from a defined starting point (like SQL or opportunity created) to a closed-won outcome.

What sales cycle length reveals

Sales cycle length tells you how quickly pipeline turns into booked revenue. That matters because most operating decisions assume some "velocity":

- How much pipeline you need to hit a number

- How early you must start selling to land next quarter's bookings

- How much cash you burn before deals convert

- Whether adding sales capacity now will pay back soon enough

The Founder's perspective

If your cycle is 90 days and you want to double next quarter, you cannot "start in quarter." You must already have qualified opportunities moving. Sales cycle length is a constraint on growth, not just a reporting metric.

A useful way to think about it: sales cycle length is the time dimension of your go-to-market. Pair it with Win Rate (conversion) and ACV (deal size) to understand whether you have a volume problem, a conversion problem, or a time problem.

How it is calculated (without fooling yourself)

At the deal level, it is simply the number of days between two timestamps:

Where teams get into trouble is picking inconsistent start dates. Common "start date" options:

- Lead created (includes marketing wait time; useful for end-to-end demand gen)

- MQL (depends heavily on your definition of MQL)

- SQL (a good default if SQL is consistently enforced)

- Opportunity created (best for CRM pipeline mechanics)

- First meeting held (useful if meetings are reliably logged)

Recommendation for most SaaS founders: track two cycles, because they answer different questions.

- SQL to closed-won: how efficient your sales process is once a lead is qualified

- Lead created to closed-won: how long cash takes from first touch (useful for planning and payback)

Then roll it up across deals. For a simple average:

Also track median cycle length. In B2B SaaS, distributions are usually lopsided: many deals close in a normal range, and a few drag on for months.

Use cohorts and segmentation, not one global number

A single blended number hides the truth. Segment cycle length by at least:

- Deal size band (proxy for complexity): use ACV (Annual Contract Value) or ASP (Average Selling Price)

- Customer type: SMB vs mid-market vs enterprise

- Source: inbound vs outbound vs partner

- Product line or plan

- Region (procurement norms vary)

- Security/compliance required (SOC 2, HIPAA, vendor risk review)

If you only do one segmentation, do it by ACV band, because it usually explains the largest portion of variance.

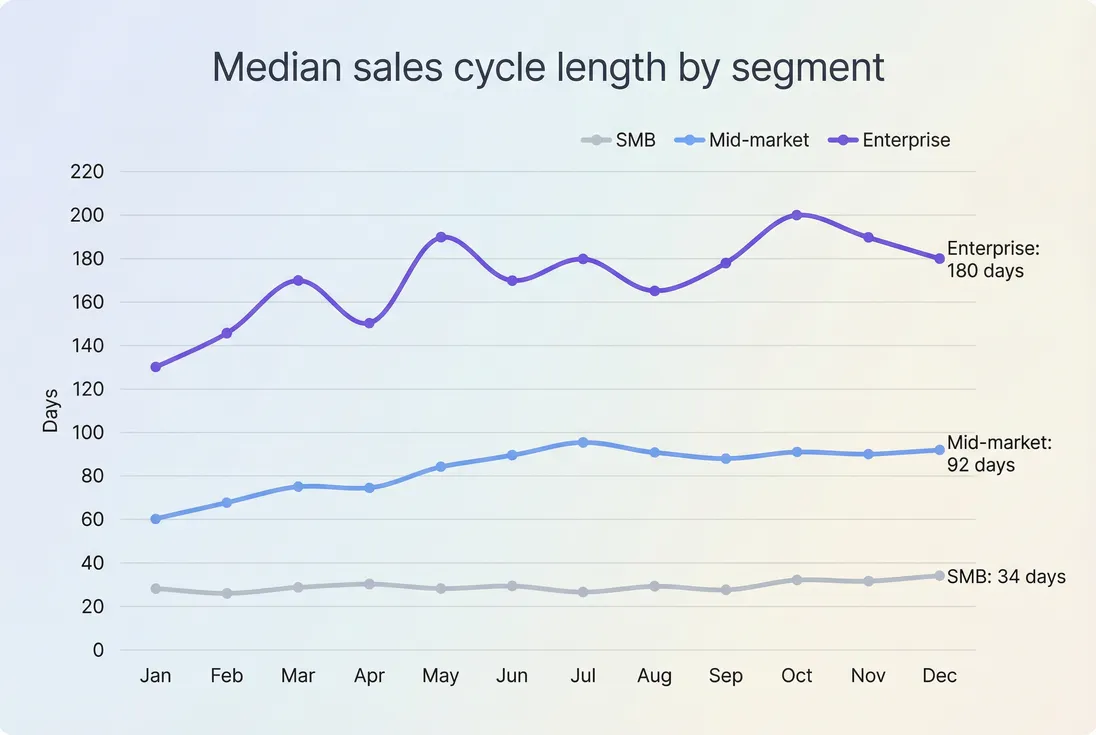

Median cycle length by segment prevents a blended average from hiding that enterprise deals are driving most timing risk.

What a "good" sales cycle looks like

Benchmarks are noisy, but founders still need ranges to calibrate expectations. Use these as directional baselines (assuming a sales-assisted motion, not pure self-serve).

| Segment (typical ACV) | Typical cycle length | What usually drives it |

|---|---|---|

| Self-serve (low ACV) | 0 to 7 days | Trial and onboarding speed |

| SMB (up to ~15k) | 14 to 45 days | Budget owner is close to user |

| Mid-market (~15k to 60k) | 45 to 120 days | More stakeholders, lighter procurement |

| Enterprise (60k plus) | 120 to 270 plus days | Security review, procurement, legal, internal alignment |

Two important founder takeaways:

- Short cycles are not automatically better. If your cycle is getting longer because you moved upmarket and ACV rose, that can improve unit economics even as timing worsens. Pair cycle length with CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost) and CAC Payback Period.

- Variance is a metric. A business with a 60-day median and tight distribution is easier to forecast than one with the same median but huge spread.

The Founder's perspective

Investors rarely punish you for having a 150-day enterprise cycle. They punish you for pretending it is 60 days in the forecast, hiring ahead of reality, and missing quarters.

What actually changes sales cycle length

Sales cycle length is not one thing. It is the sum of many waits, decisions, and handoffs—most of which live on the buyer's side.

Deal complexity and stakeholder count

Cycle length tends to increase with:

- More departments involved (security, IT, finance, legal)

- Higher perceived switching risk

- More integrations and data migration

- Higher contract value (more scrutiny)

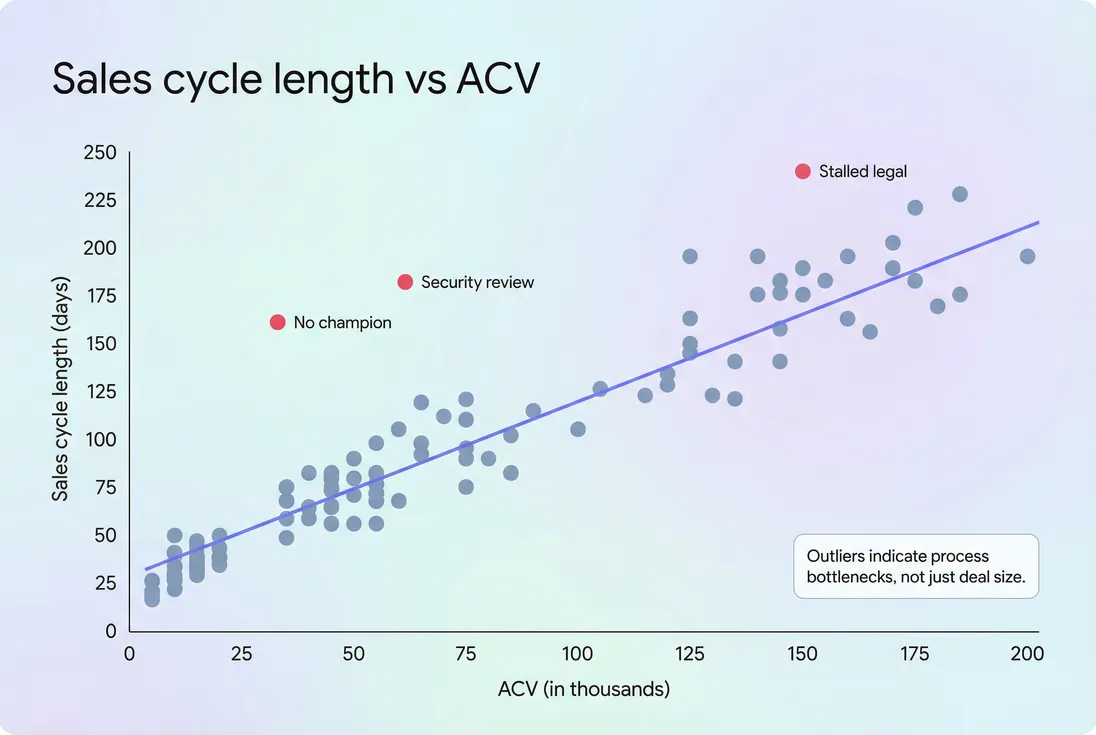

A practical diagnostic: plot cycle length vs ACV to see whether you have a normal relationship or a process problem.

Cycle length should generally rise with ACV; outliers usually indicate a fixable bottleneck like legal or security, not a pricing issue.

Your qualification standards (and courage)

Many "long cycles" are actually late disqualification.

If reps keep weak deals alive, your pipeline looks healthy, but:

- cycle length increases (because dead deals linger)

- forecast accuracy drops

- reps miss quota with lots of activity

- you over-hire because pipeline appears strong

This is why sales cycle length pairs tightly with Qualified Pipeline: improving qualification often shortens cycle and improves win rate because you stop spending time on bad-fit accounts.

Evaluation design and time-to-value

If buyers cannot quickly validate value, they delay commitment. Common culprits:

- unclear success criteria for a pilot

- implementation steps that require your engineers

- long onboarding to first result

- missing enablement for the internal champion

This is closely related to Time to Value (TTV). Even in enterprise, the fastest cycles usually come from a crisp evaluation plan and an obvious "proof moment."

Contracting, procurement, and invoicing friction

For larger deals, the slowest part is frequently not product. It is "paperwork time":

- security questionnaires and vendor risk review

- legal redlines and non-standard terms

- procurement batching cycles

- payment terms and invoicing setup

This is also where bookings vs cash diverge. You can close-won and still wait to get paid. If you are feeling cash pressure, pair cycle length with Accounts Receivable (AR) Aging to see whether the bottleneck is closing or collecting.

Pricing and discounting dynamics

Discounting can shorten cycle length if it reduces internal approval burden for the buyer—but it can also lengthen it if discounts trigger more scrutiny and negotiation.

If you change discount strategy, track:

- cycle length by discount band

- win rate by discount band

- resulting ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue) quality (are you buying deals that churn)

For deeper context, see Discounts in SaaS.

Where cycles "break" in real life

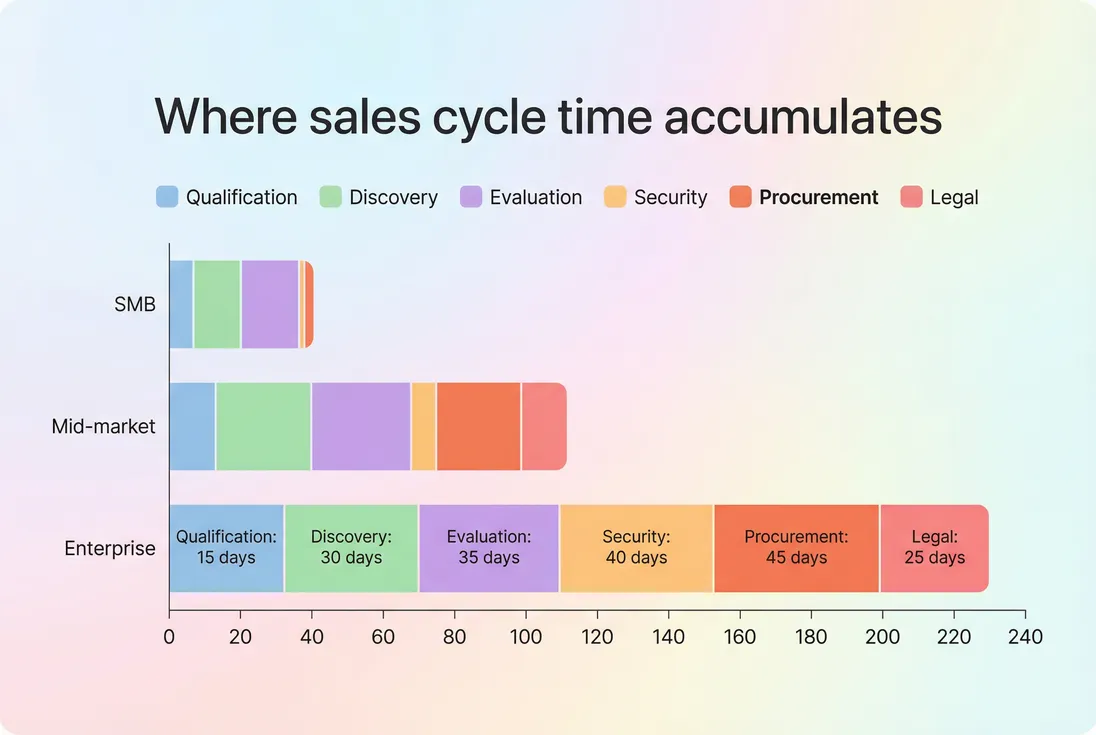

When founders say "our cycle got longer," the actionable question is: where did the time accumulate? You want stage-level time, not just total time.

A useful breakdown is "time in stage" from your CRM:

- Qualification

- Discovery

- Demo and evaluation

- Security and compliance

- Procurement

- Legal and signature

Stage-level time shows whether your cycle is slow because of selling or because of buyer process steps like security, procurement, and legal.

Patterns to watch:

- More time in qualification: lead quality declined, or reps are delaying next steps

- More time in evaluation: unclear success criteria, weak champion, poor onboarding

- Security spike: selling to regulated accounts without a prepared security package

- Procurement spike: pricing complexity, non-standard terms, or end-of-quarter batching

- Legal spike: contract redlines, missing standard fallback positions, or slow internal responses

The Founder's perspective

If security and legal time are growing, the fix is rarely "sell harder." It is enabling the buyer: pre-approved redlines, a security one-pager, faster turnaround SLAs, and a mutual close plan that names every approval step.

How founders use it to make decisions

Sales cycle length becomes powerful when you use it to answer operational questions, not just report history.

1) Forecasting and timing risk

A practical forecasting rule: if your median cycle is 60 days, then opportunities created this month should largely close in the next two months—if they match the segment and stage definitions.

What to do with that:

- Build pipeline coverage targets by segment (enterprise needs earlier creation)

- Set expectations with the team about what can close this quarter

- Reduce "hope-based" forecasts driven by late-stage deals that have not completed buyer steps

Cycle length is also a leading indicator of misses: if it starts creeping up, the quarter is at risk even if pipeline dollars look fine.

2) Hiring and capacity planning

Cycle length determines how long it takes a new rep to produce booked revenue after ramp. Longer cycles mean:

- more working capital needed to fund headcount before results

- slower feedback loops on messaging and ICP

- higher dependence on early pipeline creation and enablement

This connects directly to cash discipline metrics like Burn Rate and Burn Multiple. If you are hiring ahead of bookings while cycle length is expanding, you are increasing execution risk.

3) Choosing the right go-to-market motion

Cycle length helps validate whether you are truly:

- Sales-Led Growth (SLG) (longer cycles, higher ACV, more steps)

- Product-Led Growth (shorter cycles, faster time-to-value, less human gating)

Many teams end up in a hybrid where they carry SLG costs but fail to impose SLG rigor (qualification, mutual close plans, stage exit criteria). That hybrid is where cycles often bloat.

4) Pricing and packaging changes

When you change packaging, expect cycle length to shift because buying behavior changes:

- introducing an annual plan may add procurement steps

- moving upmarket increases stakeholder count

- adding usage-based components may trigger finance review

Track cycle length alongside ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account) or ASP (Average Selling Price) to confirm whether the "slower" motion is actually producing better economics.

5) Pinpointing process improvements that matter

Teams waste time trying to shave days from places that do not move the number. Use stage time to prioritize.

High-leverage fixes that commonly shorten cycle length:

- Mutual close plan for every qualified deal (named steps, dates, owners)

- Standard security packet (SOC 2 report, architecture overview, DPA template)

- Contract standards (pre-approved terms, fallback positions)

- Timeboxed evaluation (clear success criteria, limit pilots that have no end date)

- Faster response SLAs for legal and security questions

- Cleaner pricing (fewer one-off discounts, fewer custom clauses)

If you must discount to accelerate, treat it as an experiment and watch for second-order effects on churn and expansion (see GRR (Gross Revenue Retention) and NRR (Net Revenue Retention)).

Practical measurement rules (so your metric stays trustworthy)

If you want sales cycle length to inform decisions, enforce these rules:

- Define start and end points in writing. Put the definitions in your RevOps doc, not in someone's head.

- Use closed-won deals for core reporting. Mixing open deals creates "age of pipeline," which is a different metric.

- Track median, average, and distribution. Median for typical performance; average and percentiles for risk.

- Separate new business from expansions. Upsells often have very different cycles than new logos (see Expansion MRR).

- Segment before you conclude. A "worse" cycle may just be a better mix of larger accounts.

If you want a single operating dashboard view, use:

- median cycle length by ACV band

- percent of deals closed within target window (for each band)

- stage-level time for your top two bottlenecks

- cycle length trend paired with win rate trend

Interpreting changes without overreacting

Sales cycle length moves for good reasons and bad reasons. Here is a simple interpretation matrix:

| What changed | Likely meaning | What to check next |

|---|---|---|

| Cycle up, ACV up | Moving upmarket | Win rate by segment, stage bottlenecks, capacity plan |

| Cycle up, win rate down | Weak qualification or messaging | Lead quality, ICP fit, stage exit criteria |

| Cycle down, discounting up | Buying deals with price cuts | Retention risk, deal quality, churn later |

| Cycle down, churn up later | Overpromising or forcing closes | Onboarding, Customer Health Score, TTV |

| Cycle stable, growth slows | Pipeline volume issue | Lead volume, CPL (Cost Per Lead), conversion rates |

The point is not to chase the shortest cycle. The point is to understand what your cycle implies about cash timing, predictability, and deal quality.

If you want, share your typical ACV range, target customer (SMB vs mid-market vs enterprise), and current median cycle length. I can suggest a segmentation scheme and a realistic target range that will actually improve forecasting and payback—not just make the metric look better.

Frequently asked questions

It depends on ACV, buyer type, and complexity. Self-serve can close in minutes to days, SMB sales in 14 to 45 days, mid-market in 45 to 120 days, and enterprise often 120 to 270 plus days. Compare yourself to peers in your ACV band, not the whole market.

Track both, but use median for operating decisions. A few stalled enterprise deals can distort the average and make your process look slower than it is. The median shows the typical path to revenue, while the average highlights risk and variance you must account for in forecasting and cash planning.

Longer cycles often come from selling larger accounts, new compliance requirements, more stakeholders, or procurement and legal steps. Product improvements help, but they do not remove buyer process. Check changes in ACV, win rate, stage time, and the mix of inbound versus outbound to identify the real driver.

A longer cycle delays revenue and increases the time your sales and marketing spend sits on the balance sheet without payback. That typically worsens CAC payback period and increases cash pressure, especially if you ramp headcount ahead of bookings. Model cash timing, not just annualized contract value.

Focus on removing avoidable waiting: tighten qualification, set mutual close plans, pre-answer security and legal with standard packets, reduce custom pricing, and enforce timeboxed evaluations. Then measure stage-level time to find the biggest bottleneck. Cutting a few days at multiple stages is usually more realistic than one big fix.