Table of contents

Rule of 40

Founders care about the Rule of 40 because it compresses a messy question—"Are we growing fast enough for how much we're losing?"—into a single, board-ready signal. It's not a strategy, but it is a forcing function: it makes you quantify tradeoffs between growth and profitability instead of debating them abstractly.

Plain-English definition: the Rule of 40 is your growth rate plus your profit margin, expressed in percentage points. A combined score of 40 or higher is commonly viewed as a healthy balance for many SaaS businesses.

What the rule of 40 reveals

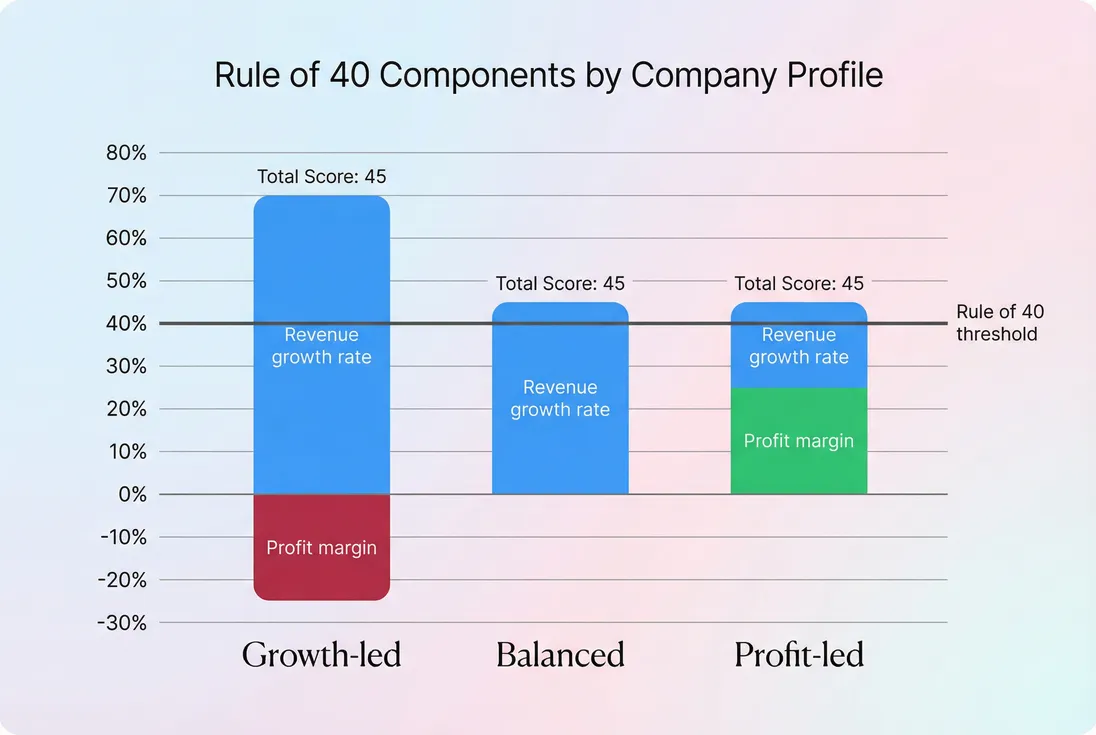

The Rule of 40 is a balance metric. It's not trying to maximize growth or maximize profit in isolation—it's asking whether the combination is strong enough to justify your spend and risk.

In practice, founders use it to answer questions like:

- Are we scaling efficiently enough to justify current burn?

- If growth slows, do we have a margin plan that keeps us "investable"?

- If we push for profitability, how much growth can we afford to give up?

A subtle but important point: because it's a sum, you can improve the score in two ways:

- grow faster at the same margin, or

- improve margin at the same growth.

That's why it's useful in planning. It lets you compare very different operating plans on a common scale.

The Founder's perspective: If your Rule of 40 is deteriorating quarter after quarter, you're losing the "benefit of the doubt." Hiring plans, sales capacity ramps, and product investments become harder to defend—because the business is taking on more cost than the growth is paying back.

What it is not

The Rule of 40 is not a replacement for fundamentals like retention, unit economics, or cash runway. It's a summary metric, and summary metrics can hide sharp edges.

You still need to understand the drivers behind growth (new, expansion, churn) and behind margin (COGS and operating expense structure). If you're not already tight on revenue definitions, start with ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue) and MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue) so your growth number is grounded in clean recurring revenue.

How to calculate it

At its simplest:

Both inputs are in percentage points, and you add them directly.

Step 1: pick a growth rate definition

Most teams use year-over-year (YoY) growth to smooth seasonality and one-time timing effects.

A standard growth calculation is:

For SaaS, the "revenue" in that formula is where things get opinionated:

- Recurring-revenue-first teams often use ARR growth (especially if professional services or one-time fees distort recognized revenue).

- Finance-led reporting often uses recognized revenue growth (GAAP/IFRS).

Pick the one that matches how you run the business, then stick with it.

Step 2: pick a margin definition

Margin is also flexible. Common options:

- EBITDA margin (most common in Rule of 40 conversations)

- Operating margin (stricter; closer to "real" profitability for mature orgs)

- Free cash flow margin (best when cash is the constraint)

A generic margin formula is:

Where "profit" depends on your chosen margin type.

Step 3: compute and sanity check

Example:

- YoY growth: 55%

- EBITDA margin: -20%

Rule of 40 score = 35.

That's below 40, but it's close—and the "diagnosis" depends on context:

- If you have long runway and retention is strong, you might accept it while you scale.

- If runway is tight, that -20% margin is the fire you need to put out.

A practical definition to document internally

Most SaaS teams do well with this operating definition:

- Growth: YoY ARR growth (or YoY recurring revenue growth)

- Margin: trailing-twelve-month EBITDA margin

Why? It aligns to how SaaS is managed (recurring revenue) while smoothing short-term volatility (TTM).

If you're actively managing burn, pair Rule of 40 with Burn Rate and Runway so you don't "win" the score while accidentally running out of cash.

What moves the score

Treat Rule of 40 as two dials: growth and margin. Your job is to understand what operational levers move each dial without breaking the other.

Growth levers (without hand-waving)

SaaS growth is usually some mix of:

- New bookings (new customers, new logos)

- Expansion (upsells, seat growth, usage growth)

- Churn and contraction (customers leaving or downgrading)

This is why retention metrics matter so much. Improving retention often raises growth and helps margin by reducing the need to "replace" lost revenue.

Useful driver metrics to connect:

- NRR (Net Revenue Retention) for the expansion-versus-churn balance

- GRR (Gross Revenue Retention) for how much baseline revenue you keep

- Net MRR Churn Rate if you manage on monthly recurring movements

If you track revenue movement monthly, you'll often find that the fastest path to a better Rule of 40 score is not "more pipeline"—it's reducing churn and improving expansion. Those changes compound.

Margin levers (the ones that last)

Margins improve through a few predictable mechanisms:

- Gross margin improvement: hosting costs, support load, third-party vendor costs

Start with Gross Margin. - Sales efficiency: CAC payback, win rate, cycle length, discount discipline

Useful references: CAC Payback Period, Discounts in SaaS, Sales Cycle Length. - Operating discipline: slowing headcount growth, reducing tool sprawl, right-sizing G&A

(But be careful—some cuts reduce growth with a lag.)

The highest-leverage "both dials" moves

Some initiatives move growth and margin in the same direction:

- Pricing and packaging cleanup: fewer deep discounts, better value metrics, clearer tiers

Related: ASP (Average Selling Price) and ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account). - Retention work that reduces churn reasons: onboarding, reliability, product gaps

Related: Churn Reason Analysis and Cohort Analysis. - Expansion mechanics: seat-based expansion, usage-based expansion, better upgrade paths

Related: Expansion MRR and Usage-Based Pricing.

The Founder's perspective: If you need a fast Rule of 40 lift, don't default to layoffs or "grow at all costs." First look for moves that improve retention, pricing, and expansion. Those usually increase growth while also improving the margin profile via better revenue per employee and lower CAC pressure.

What good looks like

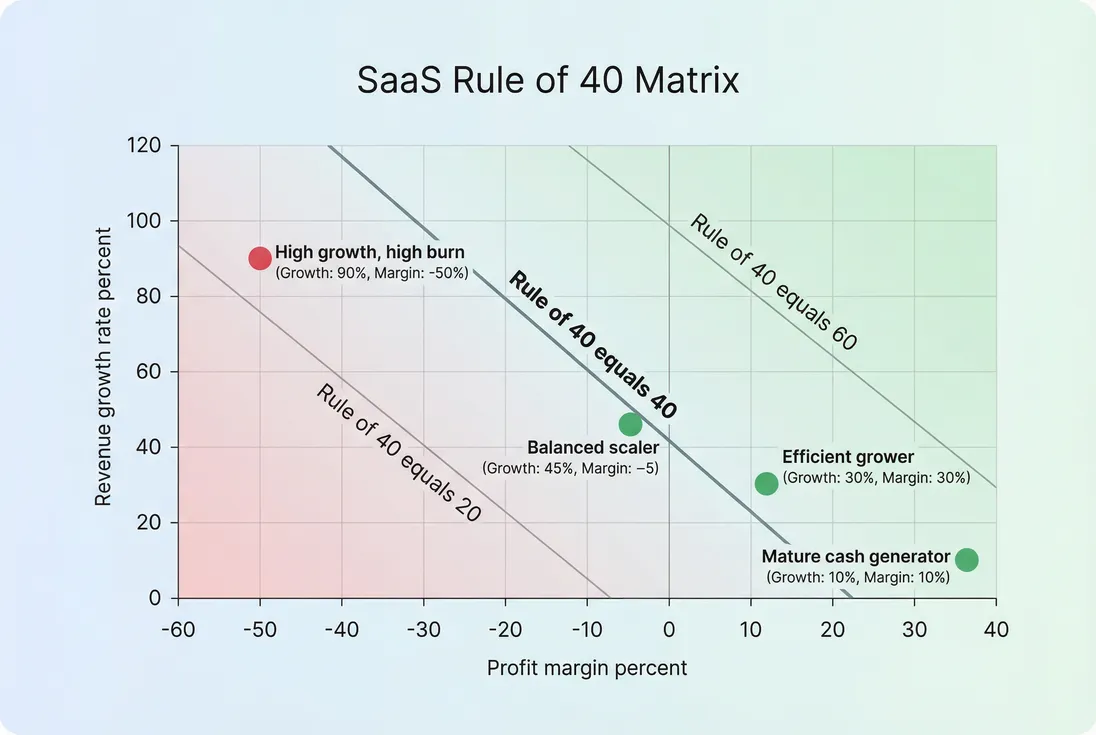

"40" became a shorthand because it often mapped to strong long-term outcomes in public SaaS comps. But founders should treat it as a contextual benchmark, not a universal law.

Here's a practical way to interpret it by stage:

| SaaS stage (rough) | Common reality | How to use Rule of 40 |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-$1M ARR | Volatile growth, negative margins, experimentation | Track directionally. A single quarter means little. Use it to prevent uncontrolled burn. |

| $1M–$10M ARR | Clearer GTM motion, heavy reinvestment | Aim to improve trendline. If far below 40, ensure you can explain why and how it changes. |

| $10M–$50M ARR | Scaling teams, repeatability expected | 40 becomes a real operating guardrail. Investors expect a plan to reach/hold it. |

| $50M+ ARR | Efficiency and predictability matter more | Scores above 40 often correlate with premium valuation and strategic flexibility. |

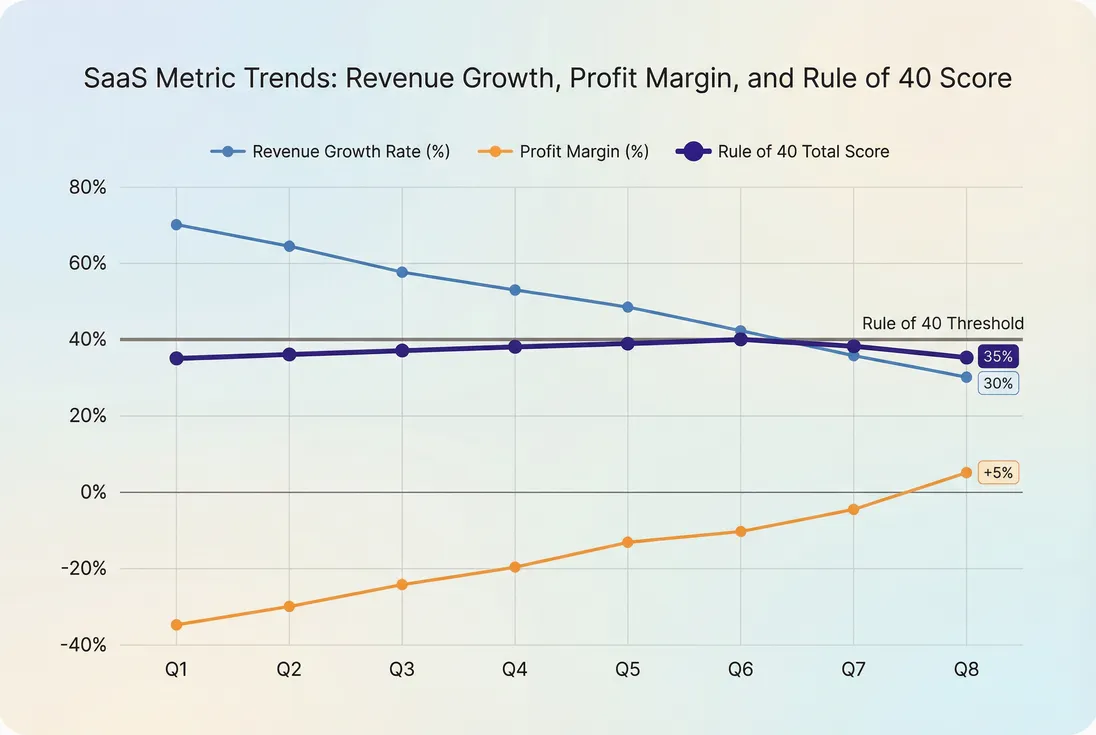

Interpreting changes (what it usually means)

- Score up because growth rose: good—if it's durable (not pulled forward with heavy discounting).

- Score up because margin rose: good—if you didn't cut the drivers of next-quarter growth.

- Score down while growth is still high: watch your cost structure; you may be "buying" growth inefficiently.

- Score down because growth slowed: diagnose churn, pipeline quality, and sales efficiency before cutting deeper.

To avoid whiplash, many teams track it on a trailing basis (TTM growth + TTM margin) and review it quarterly. For capital conversations, pair it with Capital Efficiency and Burn Multiple. A company can "hit 40" in ways that still destroy cash (for example, through accounting timing or short-term cuts that don't stick).

How founders use it in decisions

The Rule of 40 becomes useful when you turn it into an operating constraint, not just a reporting number.

1) Set a target band, not a point

Instead of "we must be at 40," use a band tied to strategy:

- Aggressive land-grab year: 30–40, with clear milestones and runway protection

- Normal scaling: 40–55

- Efficiency year or pre-exit: 50+

Then define what "breaks glass" if you fall below the band (pause hiring, freeze experiments, reprice, etc.).

2) Use it to sanity-check plans

A plan that says "grow 60% and improve margin by 15 points" might be real—or fantasy. The Rule of 40 forces the conversation:

- What specific levers create the 60%?

- What cuts or efficiencies create the 15 points?

- What are the risks to retention, win rate, and pipeline?

This is where connecting to your recurring revenue system matters. If you manage on recurring revenue, your growth plan should reconcile to drivers like New Acquisitions, Logo Churn, and Expansion MRR.

3) Diagnose the source of change

When the score moves, don't stop at "up or down." Break it into two component deltas:

- Did growth change?

- Did margin change?

Then push one level deeper:

- If growth changed, was it new sales, expansion, or churn?

- If margin changed, was it gross margin, S&M efficiency, or overhead?

If you're looking at revenue movement, a clean way to do this is by segmenting recurring revenue drivers (new, expansion, churn) and validating retention patterns with Cohort Analysis. The goal is to avoid "false improvements," like temporarily cutting acquisition spend and celebrating a margin bump while next-quarter growth collapses.

The Founder's perspective: A "stable" Rule of 40 can hide a major transition: slowing growth covered up by profitability improvements. That can be exactly what you want (maturity) or a red flag (growth engine weakening). Your job is to decide which story is true and act early.

When it breaks

The Rule of 40 is popular because it's simple. The cost of simplicity is that it can mislead in a few common situations.

1) Early-stage volatility and tiny denominators

When revenue is small, growth rates are extreme and noisy. A single deal can swing YoY growth by 30 points. In this phase, use the metric as a loose guardrail, and lean more on runway plus retention direction.

2) Revenue definition mismatches

If you mix ARR growth one quarter and recognized revenue growth the next, your "trend" is not real. The same goes for margin definitions. Document your inputs, then keep them consistent.

If you have significant one-time items (implementation fees, refunds, chargebacks), make sure you understand how they flow into your top line:

3) Usage-based and seasonal businesses

Usage-based models can have real demand volatility. That doesn't mean the Rule of 40 is useless—but you should expect wider swings and rely on trailing periods (TTM) to smooth noise.

4) It doesn't tell you how you got there

Two companies can both score 45:

- one has strong retention and efficient acquisition,

- the other is discounting heavily and deferring problems.

That's why you should pair it with driver metrics:

- Retention quality: GRR (Gross Revenue Retention) and NRR (Net Revenue Retention)

- Go-to-market efficiency: CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost) and CAC Payback Period

- Cash discipline: Burn Multiple and Burn Rate

5) It can encourage short-term behavior

You can temporarily improve margin by cutting acquisition or support, and the score will look better before growth damage shows up. Use it with a lag-aware mindset: evaluate changes over 2–4 quarters, not 2–4 weeks.

If you treat the Rule of 40 as a scoreboard, it's easy to game. If you treat it as a constraint for planning—and consistently decompose it into growth and margin drivers—it becomes one of the fastest ways to align your team, your board, and your cash reality.

Frequently asked questions

A score of 25 means your growth plus profitability is below the common 40% "healthy balance" bar. It does not automatically mean you are failing, but it signals tradeoffs: either growth is too slow for your losses, or losses are too deep for your growth. Use it to guide focus and pacing.

Use the growth rate that matches how your business is valued and managed. Many SaaS teams use ARR growth for recurring businesses, especially if services are material. Investors often cite revenue growth (GAAP/recognized). Pick one definition, document it, and keep it consistent so trends are meaningful.

EBITDA margin is the most common because it approximates operating profitability before capital structure and some accounting noise. Operating margin is stricter and useful for mature companies. Free cash flow margin is best when cash efficiency is the real constraint. Don't mix margins across periods or comparisons.

Not always. Early-stage SaaS often runs below 40 because you are buying growth and building product. The more important question is whether your score is improving and whether the gap is intentional and financed (runway). As you scale, stakeholders expect the score to drift toward 40 and beyond.

First, fix "waste" before cutting muscle: address churn, pricing leakage, and low-performing acquisition channels. Improvements in retention and ARPA often lift both growth and margin. Then use scenario planning: if you reduce spend, model the likely growth deceleration and decide whether the score truly improves over 6–12 months.