Table of contents

Revenue per employee

Founders rarely run out of ideas—they run out of productive capacity. Revenue per employee is the quickest "sanity check" for whether your team size matches your revenue reality, and whether new hires are turning into durable output or just added coordination.

Revenue per employee is the amount of revenue your company generates per full-time equivalent (FTE) employee over a given period (typically a year, or annualized).

What this metric reveals

Revenue per employee is an efficiency lens, not a growth metric. It helps you answer questions like:

- Are we hiring ahead of revenue (intentionally), or drifting into bloat (unintentionally)?

- Does our go-to-market motion scale cleanly, or does it require linear headcount?

- Are product and support investments translating into higher monetization and retention?

Most importantly, it forces a conversation about capacity allocation: how much of your team is building, selling, and supporting the current business versus building future optionality.

The Founder's perspective, revenue per employee is a "truth serum" in headcount planning. If you can't explain why the metric is falling—and what will reverse it—your hiring plan is probably hope-based, not model-based.

How to calculate it cleanly

At its simplest:

Two choices determine whether this metric becomes useful or misleading: the revenue definition (numerator) and the headcount definition (denominator).

Choose the right revenue numerator

For SaaS, there are three common numerators:

ARR (recommended for most SaaS operating decisions)

Use ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue) if your business is primarily subscription and you want a number that aligns with recurring scale.Annualized MRR (fine for earlier stage)

If you operate in monthly terms, use MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue) annualized. This is close to ARR for many businesses, but be careful if you have annual contracts, ramp deals, or heavy mid-period changes.Trailing twelve months recognized revenue (best for GAAP-style realism)

Use recognized revenue when you want the metric to align with financial statements and cash planning. This matters more if you have meaningful services, usage-based variability, or revenue recognition complexity. See Recognized Revenue and Deferred Revenue.

Rule of thumb: if you're discussing hiring capacity against recurring scale, use ARR. If you're discussing profitability and financial reporting, use trailing twelve months recognized revenue.

Define headcount as average FTE

Use average FTE headcount over the period, not end-of-period headcount. End-of-period will exaggerate changes when you hire (or lay off) late in the period.

Practical guidance:

- Convert part-time and contractors into FTE (for example, 0.5 for half time).

- Include contractors who function like staff (ongoing engineering, support, RevOps).

- Exclude one-time agencies that don't represent ongoing operating capacity, but be consistent.

Pick a time window that matches reality

Revenue is noisy month-to-month; headcount changes in steps. Most founders get the cleanest signal using:

- Quarterly tracking with an annualized revenue numerator, or

- A trailing twelve month revenue numerator with trailing average headcount

If you want smoother operational tracking, consider using T3MA (Trailing 3-Month Average) for the numerator and denominator.

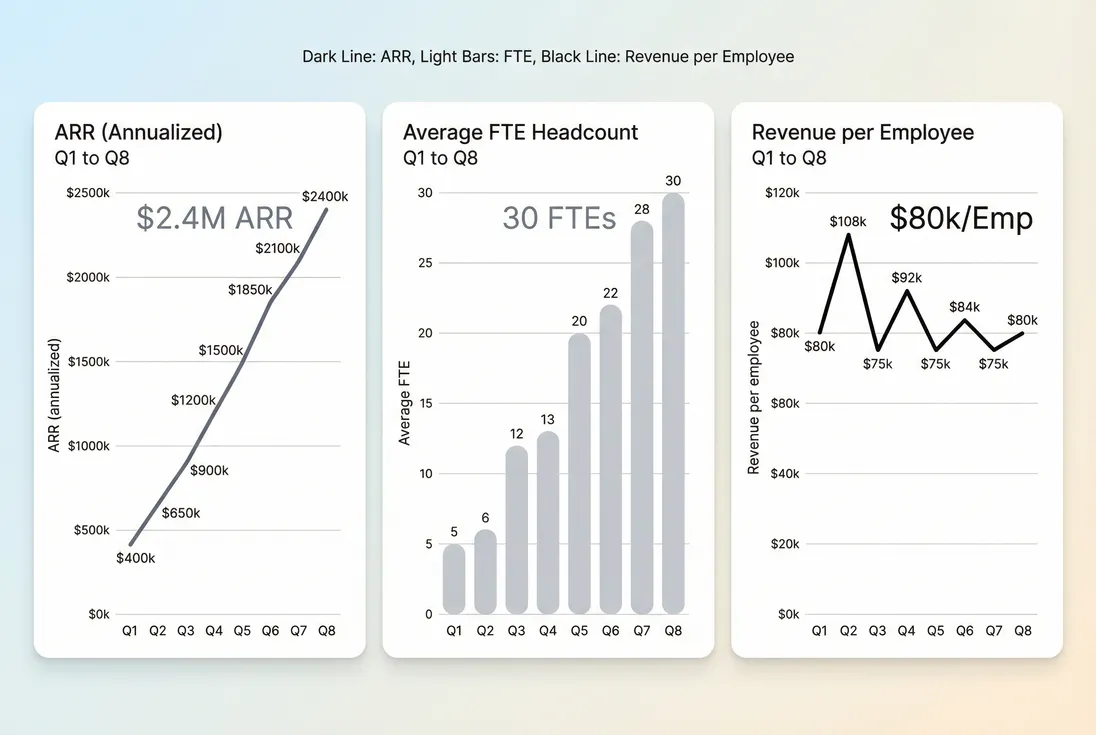

Separating ARR growth, headcount growth, and revenue per employee shows whether efficiency dips are temporary (hiring ahead) or persistent (capacity not converting into revenue).

What drives the number

Revenue per employee moves for only two reasons: revenue changes or headcount changes. But founders need the operational drivers behind those two levers.

Revenue-side drivers (how you monetize output)

In SaaS, revenue output is heavily shaped by:

Pricing and packaging

If you raise ASP (Average Selling Price) or improve packaging, revenue can rise without proportional headcount. Pricing work is one of the highest-leverage ways to move revenue per employee.Customer count and ARPA

A useful mental model is that revenue is roughly customers × ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account). If customer growth is expensive in headcount (sales and onboarding), ARPA must justify it.Retention and expansion

Strong NRR (Net Revenue Retention) lets you grow revenue without linearly growing acquisition headcount. Weak retention forces you to "run faster to stand still." Track GRR (Gross Revenue Retention) alongside NRR to understand whether expansion is masking churn.Sales execution efficiency

If pipeline quality, win rate, or sales cycle issues require more reps to hit the same bookings, revenue per employee deteriorates. See Sales Efficiency and Win Rate.

Headcount-side drivers (how much capacity you carry)

Revenue per employee falls when you add capacity faster than revenue compounds. Common causes:

Hiring ahead of plan (sometimes correct)

Adding a sales pod or a customer success function can cause a predictable dip before the revenue shows up.Role mix changes

Shifting from product-heavy to GTM-heavy headcount often raises revenue later, but may lower it short-term. Similarly, adding support and success might reduce revenue per employee while protecting retention (which can be the right trade).Operational drag

Too many meetings, slow releases, fragile infrastructure, and internal rework make each employee "produce less revenue," even if they are talented. If you suspect this, look at delivery speed, incident volume, and time-to-value. See Time to Value (TTV) and Technical Debt.

The Founder's perspective, don't treat revenue per employee like a vanity benchmark. Treat it like a constraint: if you plan to double headcount, you should have a crisp, testable story for how revenue will grow faster than coordination costs.

How to interpret changes month to month

The most common founder mistake is reading revenue per employee as a weekly or monthly "score." It behaves more like a wave than a dial.

A simple interpretation framework

- Up and to the right: revenue growth is outpacing headcount growth (good, but confirm you're not under-investing in product, security, or support).

- Flat: you're scaling revenue and team roughly linearly (common in services-heavy or enterprise onboarding-heavy motions).

- Down: either you hired ahead (planned) or you're accumulating inefficiency (unplanned). The difference is whether leading indicators improve.

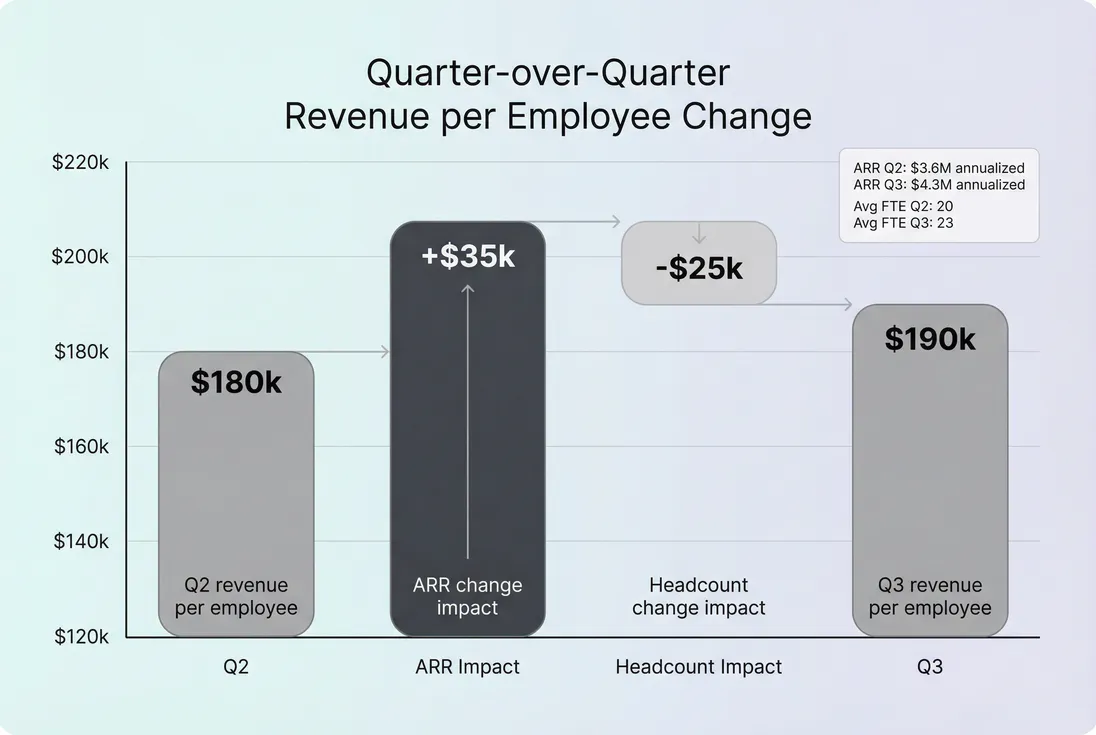

Separate planned dips from real problems

A planned dip usually has:

- A clear hiring thesis (new segment, new outbound motion, new onboarding team)

- A defined payback window (for example, 6–12 months)

- Leading indicators improving (pipeline, activation, retention, expansion)

An unplanned dip often has:

- Hiring across many functions without a specific bottleneck

- No change in retention or sales productivity

- Rising support load or engineering rework without product output gains

A bridge view forces clarity: did efficiency change because revenue grew, because headcount grew, or both?

Benchmarks by stage and model

Benchmarks are tricky because revenue per employee is heavily influenced by:

- GTM motion (PLG vs enterprise sales)

- Services or implementation intensity

- Revenue recognition and contract structure

- Customer complexity (SMB vs mid-market vs enterprise)

Still, founders need ranges to sanity check themselves. Below are directional ARR-per-employee ranges for SaaS (not rules):

| Company stage (typical) | Common ARR per employee range | What usually explains "low" |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-seed / early build | $0–$100k | Pre-revenue, product build, founder-led sales |

| Seed | $100k–$250k | Hiring ahead of repeatable acquisition, heavy onboarding |

| Series A | $200k–$400k | Scaling GTM, building CS and support, maturing infra |

| Series B+ (efficient) | $300k–$600k+ | Strong retention, scalable acquisition, high ARPA |

| Public SaaS (varies widely) | $300k–$800k+ | Depends on gross margin, services, and complexity |

How to use this table:

- Don't chase the top end if you're still finding product-market fit.

- Compare yourself to companies with similar ARPA and sales cycle length (see Sales Cycle Length and ACV (Annual Contract Value)).

- Track your trajectory as you move from founder-led to process-led growth.

The Founder's perspective, the only benchmark that really matters is your own plan: if your hiring plan implies revenue per employee will fall for 2–3 quarters, you should know exactly which metric will rise first to prove the plan is working.

How founders use it for real decisions

Revenue per employee becomes powerful when you use it alongside a few other metrics to answer specific operating questions.

1) Hiring plans and capacity math

If you have a target ARR next year and a realistic revenue per employee target, you can back into a rough headcount envelope.

Example:

- Current ARR: $4M

- Target ARR in 12 months: $7M

- Current headcount: 25 FTE

- Current ARR per employee: $160k

- Target ARR per employee (next year): $200k

That plan implies you can't just scale headcount linearly with ARR. You need either:

- Higher ARPA/ASP, or

- Better retention/expansion, or

- More productive GTM (pipeline, win rate, sales cycle), or

- Less operational drag per customer

This is where pairing the metric with Burn Rate and Burn Multiple helps. If revenue per employee is falling and burn multiple is rising, you're paying more for less growth—usually a red flag.

2) GTM motion choice (PLG vs sales-led)

Revenue per employee often surfaces whether your motion is structurally scalable:

- A healthy PLG motion can maintain high revenue per employee because acquisition and onboarding are productized.

- A sales-led motion can still be efficient, but it relies on high ACV and good retention to offset the higher GTM headcount.

If you're sales-led with low revenue per employee, look first at:

- CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost) and CAC Payback Period

- Win rate and sales cycle length

- Onboarding completion and time-to-value

3) Retention investments that "look inefficient" short-term

Adding customer success or support can reduce revenue per employee immediately. The payoff is usually in:

- Higher NRR (expansion and reduced contraction)

- Lower Logo Churn and MRR Churn Rate

- Improved customer lifetime value (see LTV (Customer Lifetime Value))

A good operating practice is to define the intended retention lift (and timeline) before hiring, then validate it using retention and cohort views (see Cohort Analysis).

4) "Are we enterprise-ready?"

Enterprise features (security, compliance, uptime, integrations) often reduce revenue per employee short-term because they add non-revenue headcount. The right question is whether those hires unlock:

- Higher ACV and ASP

- Lower churn via stickier deployments

- Faster expansion

Use this metric in combination with Gross Margin and COGS (Cost of Goods Sold) so you don't confuse revenue efficiency with profit efficiency.

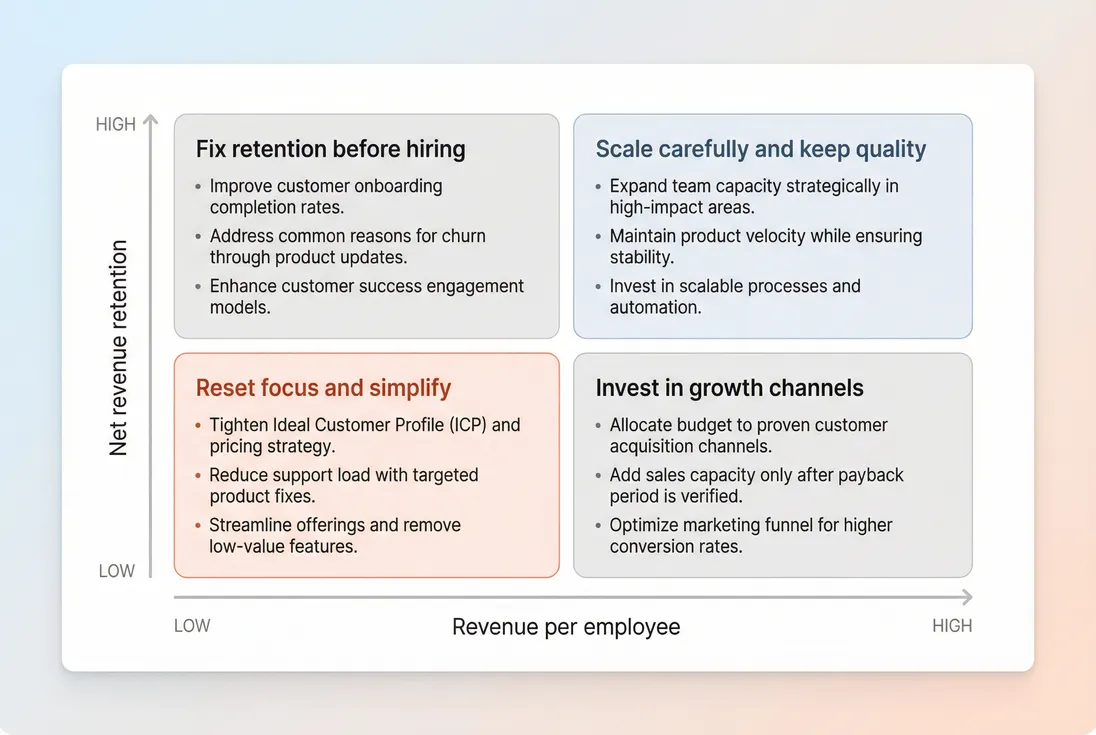

Revenue per employee is most actionable when paired with retention: low efficiency plus weak NRR is a fundamentally different problem than low efficiency with strong NRR.

When the metric breaks

Revenue per employee is simple, which is why it's easy to misuse. Watch for these failure modes:

One-time revenue and services distortions

If you have meaningful implementation, training, or one-time payments, revenue per employee may look strong even if recurring revenue quality is weak. Cross-check with MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue), CMRR (Committed Monthly Recurring Revenue), and retention.

Annual prepay and revenue recognition timing

If you're mixing cash receipts with recognized revenue, you can accidentally "pump" the numerator. Understand Deferred Revenue versus recognized revenue so you don't celebrate cash timing as efficiency.

Hiring waves create predictable dips

A step-function in headcount will almost always drop revenue per employee temporarily. Use a quarterly view and evaluate against a payback window, not against last month.

Outsourcing hides real capacity

A company with low headcount but heavy contractors can appear extremely efficient until the bills arrive (or delivery quality suffers). Convert contractors to FTE equivalents if they represent ongoing capacity.

Comparing across very different models

A low-touch SMB SaaS and an enterprise SaaS with heavy security and onboarding are not comparable. Use peer sets with similar ACV, sales cycle, and support intensity.

How to improve it without harming the business

There are only two sustainable paths: increase revenue output or reduce capacity required per dollar of revenue. The trap is trying to "improve" the metric by starving critical work.

Improve revenue output (usually the highest leverage)

Pricing and packaging work

Raise ASP, introduce value-based tiers, or adjust discounting discipline (see Discounts in SaaS). Small pricing wins compound across every future customer.Retention and expansion first

Improving NRR lifts revenue without needing proportional acquisition headcount. Invest in activation, onboarding completion, and expansion motions. Use churn analysis to focus (see Churn Reason Analysis).Tighten ICP and qualification

Selling to customers who don't get value creates churn, support load, and low expansion. Improve qualification and reduce mis-sold deals (see Qualified Pipeline).

Reduce capacity per dollar (make the company less "labor linear")

Productize onboarding and support If support load scales linearly with customers, revenue per employee will cap out. Improve onboarding completion and reduce friction (see Customer Effort Score and Onboarding Completion Rate).

Reduce operational drag Fix the recurring issues: incident volume, brittle releases, and manual billing workflows. Reliability work can feel "non-revenue," but it often pays back as faster product iteration and lower support burden (see Uptime and SLA).

Improve GTM productivity before adding headcount Before hiring more reps, improve win rate, shorten sales cycle, or raise ARPA. Otherwise you're buying growth at an increasingly expensive exchange rate.

The Founder's perspective, the best time to care about revenue per employee is before you hire. After you hire, it's too late to discover you were funding confusion instead of a constraint.

A simple operating cadence

To make revenue per employee decision-useful, keep it consistent and paired with the right companions:

- Track quarterly (and optionally trailing twelve months)

- Use ARR (or annualized MRR) plus average FTE

- Review alongside:

- Revenue Growth Rate

- NRR (Net Revenue Retention) and GRR (Gross Revenue Retention)

- Burn Multiple and Burn Rate

- Gross Margin if services or infra costs are meaningful

If revenue per employee is improving while retention is falling, you may be "optimizing" by under-serving customers. If it's falling while retention and growth are improving, you may be investing correctly—just confirm the payback window and leading indicators.

The goal isn't to maximize revenue per employee in isolation. The goal is to build a company where revenue scales faster than complexity.

Frequently asked questions

For most seed to Series A SaaS companies, a useful "healthy range" is often roughly $100k to $250k per employee on an ARR basis, depending on GTM motion. PLG and self-serve can look higher earlier; enterprise and services-heavy models often look lower until scale. Track trends, not single months.

Use the revenue definition that matches the decision. For hiring capacity and valuation conversations, ARR is usually the cleanest for SaaS. For finance reporting and profitability planning, use trailing twelve months recognized revenue. Avoid mixing bookings and revenue. If you change definitions, restate history so the trend stays comparable.

Not automatically. This metric is lagging: you hire first, revenue follows later. A short-term dip is expected when you add sales capacity, support, or a second product team. The key is payback: if ARR growth accelerates and retention holds, the temporary drop is a planned investment, not inefficiency.

Convert everyone into full-time equivalents so the denominator reflects real capacity. Example: two half-time contractors equal one FTE. Include contractors who contribute ongoing operating capacity (support, engineering, sales ops). Exclude short, one-off agency projects if they are truly non-recurring. Consistency matters more than perfection.

You improve it by increasing revenue output per unit of capacity: raise ARPA through pricing and packaging, improve retention and expansion, shorten time to value, and reduce operational drag. On the cost side, simplify onboarding, improve product reliability, automate billing and support workflows, and avoid premature hiring in low-signal channels.