Table of contents

Operating margin

Operating margin is the difference between a SaaS that can scale and one that only grows by constantly injecting cash. It tells you whether your revenue engine is starting to fund the company—or whether every new dollar of revenue still requires disproportionate spending to deliver the product, support customers, and run the business.

Operating margin is the percent of recognized revenue left after COGS and operating expenses (R&D, sales and marketing, and G&A), before interest and taxes.

If operating margin is improving, you're usually getting one (or more) of these right: pricing, retention, gross margin, sales efficiency, or headcount discipline. If it's deteriorating, you're buying growth inefficiently—or your cost structure is drifting out of control.

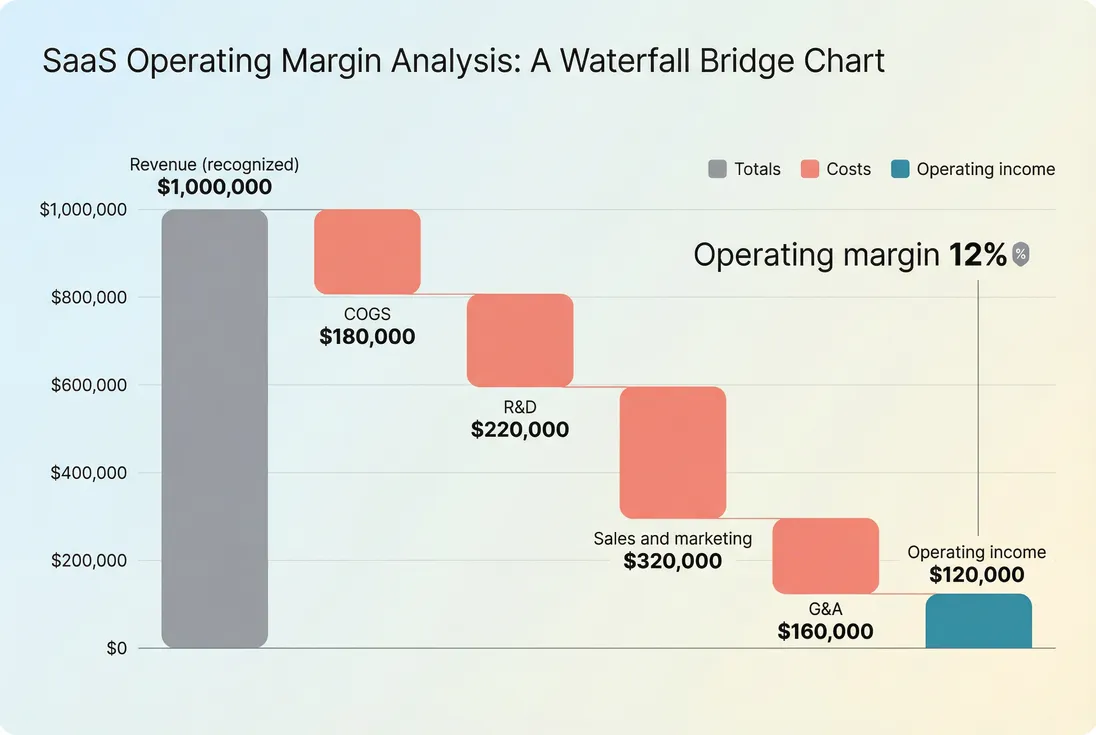

A waterfall view makes operating margin intuitive: recognized revenue minus COGS and operating expenses equals operating income, and operating margin is operating income as a percent of revenue.

What operating margin reveals

Operating margin answers a question founders face every quarter:

Are we building a business that will eventually throw off profit, or are we accumulating complexity and spend as fast as we accumulate revenue?

In practice, it reveals four things that revenue growth alone hides:

- Whether your cost structure is scaling. If revenue is up 30% but operating margin is flat or worse, your organization is getting more expensive per dollar earned.

- How "real" your go-to-market performance is. Strong pipeline can coexist with weak operating margin if sales and marketing spend is ballooning or payback is stretching. Tie the story back to CAC Payback Period and Burn Multiple.

- How resilient you are to shocks. Churn spikes, pricing pressure, or cloud cost jumps show up quickly. Pair this with retention metrics like NRR (Net Revenue Retention) and Logo Churn.

- How close you are to "default alive." Improving operating margin reduces dependence on fundraising and increases strategic options (M&A, pricing experiments, market expansion).

The Founder's perspective

I don't use operating margin to shame the team for spending. I use it to decide pace: how aggressively we can hire, how much inefficiency we can tolerate while finding product-market fit, and when it's time to shift from growth-at-all-costs to durable, compounding economics.

How to calculate it

Operating margin is calculated from your P&L (income statement), using recognized revenue—not cash collected and not bookings.

Step 1: compute operating income

Where:

- Revenue = recognized subscription revenue (and any recognized usage revenue).

- COGS = costs required to deliver the service (hosting, third-party infrastructure, customer support if you treat it as delivery, payment processing in some models). See COGS (Cost of Goods Sold) and Gross Margin.

- Operating expenses (OpEx) typically include:

- R&D (engineering, product, design)

- Sales and marketing (sales comp, marketing programs, SDRs)

- General and administrative (finance, HR, legal, exec)

Step 2: divide by recognized revenue

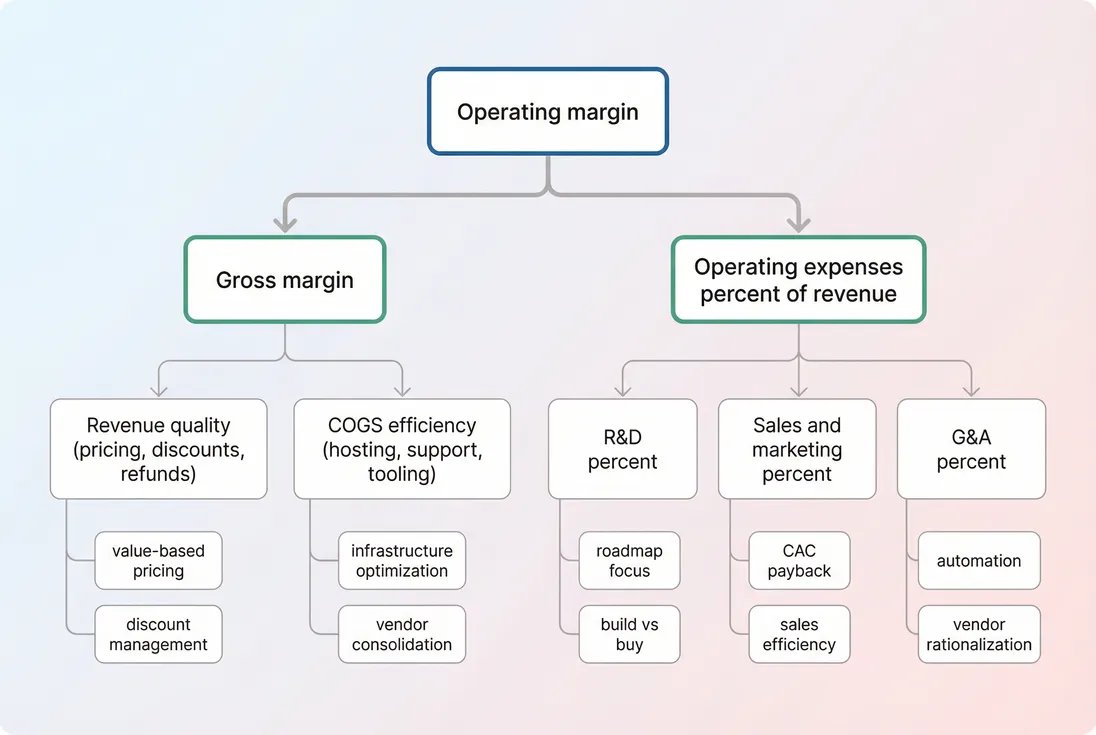

A helpful interpretation is that operating margin is basically:

- your gross margin minus

- your OpEx as a percent of revenue

That framing is useful because it tells you whether margin changes are coming from delivery economics (COGS) or from organizational spend (OpEx).

Common definition traps

Founders get whiplash from operating margin because different companies calculate it differently. Decide what you're using, document it, and be consistent.

1) GAAP vs "adjusted" operating margin

Many teams exclude "one-time" items (severance, litigation) and stock-based compensation to show an adjusted view. That's fine if you track both and don't pretend adjusted is the same as real profitability.

2) Capitalized software and R&D

If you capitalize some development costs, operating margin will look better even though cash didn't improve. Know your accounting policy and don't compare your margin to peers without adjusting for this.

3) Annual prepay and revenue timing

If you sell annual contracts, cash can be strong while operating margin looks weak because revenue is recognized over time. This is where Deferred Revenue matters.

What moves the margin

Operating margin moves for only a few fundamental reasons. The value is in diagnosing which lever is actually changing.

Pricing and packaging

A well-executed price increase often improves operating margin faster than any other lever, because most operating expenses don't increase proportionally overnight.

- Raising price increases revenue immediately (or at renewal)

- COGS usually rises much more slowly (especially for seat-based models)

- OpEx doesn't automatically rise

Pricing changes should be evaluated alongside ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account) and ASP (Average Selling Price), because margin improvement via pricing is strongest when you're not offsetting it with higher discounting. If discounting is creeping up, see Discounts in SaaS.

Retention, expansion, and churn

Churn is a margin killer in disguise. Even if expenses don't change, churn reduces the revenue denominator, which makes OpEx ratios worse and compresses operating margin.

- If churn rises, operating margin often falls even if you didn't hire anyone

- If expansion improves (Expansion MRR), operating margin often improves because the same team supports more revenue

This is why retention work can be a profitability strategy, not just a "customer success" initiative. Use Churn Reason Analysis to connect churn drivers to margin pressure.

Infrastructure and support efficiency (COGS)

Many SaaS companies under-manage COGS until it's a problem. But hosting, data tools, LLM costs, and support burden can change quickly.

Operating margin improves when:

- you negotiate committed-use discounts with providers,

- you fix inefficient queries and storage,

- you reduce ticket volume with better onboarding and product UX,

- you move upmarket where support cost per dollar tends to be lower.

This shows up first in Gross Margin, then in operating margin.

Headcount timing (OpEx)

Operating margin is highly sensitive to when you hire.

- Hiring ahead of revenue compresses margin now to (hopefully) expand it later.

- Hiring after revenue improves margin but can choke growth, product velocity, or retention.

The best operators plan hiring around "coverage" metrics: support load, pipeline coverage, engineering roadmap delivery, and onboarding bandwidth—then forecast what margin will look like after the hire and after expected revenue ramps.

The Founder's perspective

When operating margin drops, I don't ask "who spent money?" I ask "what did we just buy?" If we bought future revenue (a sales team ramp) or future retention (support capacity), the margin drop is fine. If we bought complexity or busywork, it's a warning.

How founders use it

Operating margin becomes genuinely useful when it drives specific operating decisions, not just board-slide commentary.

1) Set a hiring pace you can sustain

A simple way to operationalize margin is to translate it into a "self-funding" threshold.

If your operating margin is negative, you're funding operations with cash reserves. Combine it with Burn Rate and Runway to decide how many months you can keep hiring at the current pace.

If your operating margin is near breakeven, you can choose:

- slower growth with margin expansion (extend runway), or

- reinvest margin into growth (keep margin flat)

2) Decide whether to optimize for growth or efficiency

Pair operating margin with growth using Rule of 40. A company growing fast can justify lower margin; a company growing slowly cannot.

A practical rule:

- High growth + negative margin can be acceptable if retention and payback are strong.

- Low growth + negative margin is usually a strategic problem (positioning, pricing, churn, or bloated structure).

3) Identify whether "efficiency" is real

Margin can improve for good reasons or bad ones.

Good improvement (durable):

- price increase sticks with stable churn

- gross margin improves via infrastructure and support efficiency

- sales efficiency improves (lower CAC for same revenue)

Bad improvement (fragile):

- cutting marketing causes pipeline collapse next quarter

- freezing engineering slows roadmap and increases churn later

- delaying customer support hiring increases refunds and downgrades (see Refunds in SaaS and Contraction MRR)

4) Build an investor-grade narrative

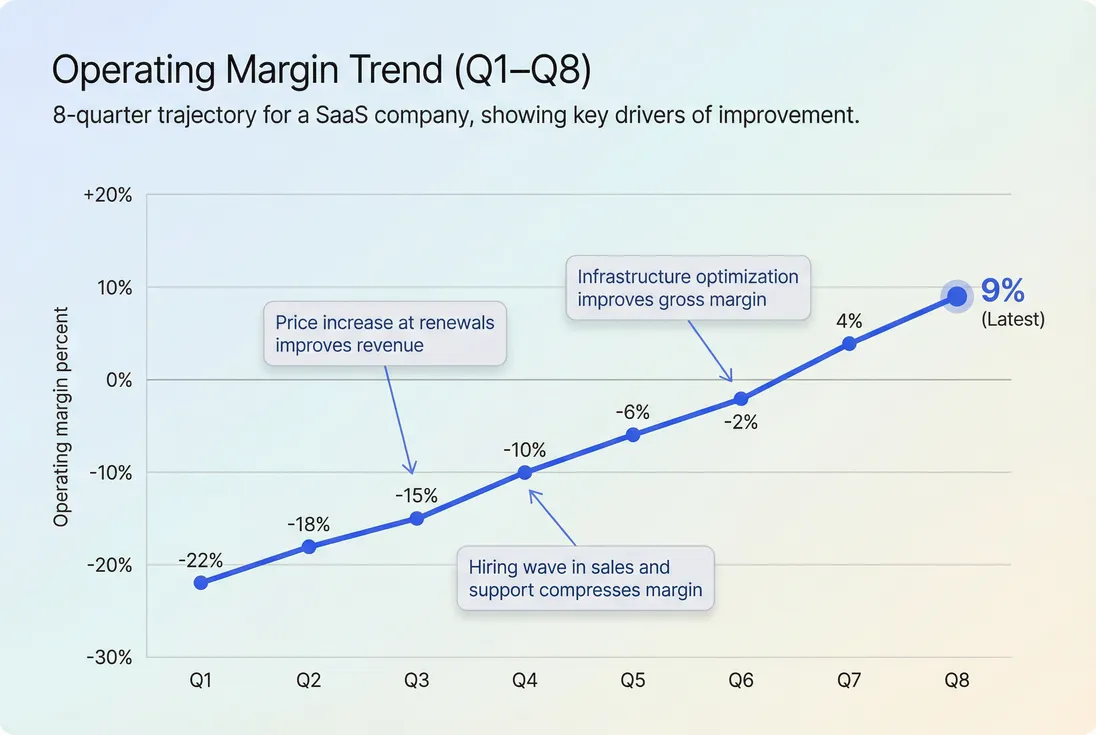

Investors want to understand not only current margin, but margin trajectory and the levers behind it. Operating margin is one of the clearest ways to show operating leverage.

Tracking operating margin over time—and annotating the real drivers—turns margin into an operating system, not a retrospective accounting outcome.

Benchmarks and targets

Operating margin benchmarks vary widely by stage and go-to-market motion. Use these as directional ranges, not universal truths.

| Stage / profile | Typical operating margin | What "good" looks like |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-PMF / seed | -100% to -20% | Margin improving quarter over quarter; clear plan to stabilize COGS and focus spend |

| Post-PMF / Series A–B | -40% to 0% | Path to breakeven without heroic assumptions; improving retention and sales efficiency |

| Scale-up / Series C+ | -10% to +15% | Operating leverage visible: revenue grows faster than OpEx |

| Efficient public SaaS | +10% to +30% | Strong gross margin, disciplined S&M, durable NRR, predictable renewals |

Two practical target-setting tips:

- Use a trailing window. A single month can be noisy; use LTM or at least a trailing average. If you like smoothing, see T3MA (Trailing 3-Month Average).

- Separate "run-rate" from "reported." If you had a one-time legal bill, report it, but also track a run-rate margin that reflects the business you're actually operating.

Where operating margin misleads

Operating margin is powerful, but founders get burned when they use it in isolation.

Cash reality can diverge

Operating margin is built on recognized revenue and accrual expenses. Cash flow is a different lens.

- Annual prepay boosts cash now but not operating margin now.

- Collections issues (late pays) can hurt cash without changing operating margin; monitor Accounts Receivable (AR) Aging.

For cash health, complement margin with Free Cash Flow (FCF) and burn metrics.

Margin can improve while the business weakens

If you cut sales and marketing hard, operating margin can jump quickly while growth decays and churn rises later. The fix is to monitor margin alongside leading indicators:

- pipeline and win rates (see Win Rate)

- retention and expansion (NRR (Net Revenue Retention))

- payback (CAC Payback Period)

Classification games distort the story

Two companies can spend the same dollars but report different operating margins based on classification:

- Putting more costs in COGS depresses gross margin and may inflate operating margin comparisons across peers.

- Capitalizing software costs improves operating margin without improving underlying efficiency.

If you're using operating margin for internal decisions, consistency matters more than perfection.

A concrete SaaS example

Assume this quarter your company has:

- Recognized revenue: $2,000,000

- COGS: $400,000 (hosting, support, tooling)

- Operating expenses: $1,500,000 (R&D $650k, S&M $550k, G&A $300k)

Operating income = $2,000,000 - $400,000 - $1,500,000 = $100,000

Operating margin = $100,000 / $2,000,000 = 5%

Now consider three common changes:

Price increase lifts revenue 8% (costs flat short-term)

Revenue becomes $2,160,000; operating income becomes $260,000; margin becomes 12%.

This is why pricing is a first-class profitability lever.You hire 6 people ahead of growth (+$180,000 OpEx)

Operating income becomes -$80,000; margin becomes -4%.

The question isn't "is -4% bad?" The question is whether those hires create durable revenue or retention lift.Cloud costs rise unexpectedly (+$80,000 COGS)

Operating income becomes $20,000; margin becomes 1%.

Here the fix is likely gross-margin work: architecture, vendor negotiations, or usage controls.

Operating margin vs nearby metrics

Operating margin is often confused with other profitability metrics. Here's the clean separation:

| Metric | What it answers | Why founders use it |

|---|---|---|

| Gross Margin | Can we deliver the service profitably? | Shows product delivery efficiency and scalability of infrastructure/support |

| Contribution margin | After variable costs, does growth pay for itself? | Useful for channel decisions and incremental spend analysis |

| Operating margin | Are we profitable after running the business? | Best single metric for operating leverage and sustainable scaling |

| EBITDA margin | Profit before non-cash and financing/tax effects | Common in financing and comps; can hide capex needs |

| Free Cash Flow (FCF) margin | Are we generating cash? | Matters for survival, debt capacity, and true self-funding |

If you're trying to improve operating margin, start by confirming gross margin is healthy, then scrutinize OpEx ratios and payback.

A simple operating cadence

If you want operating margin to inform real decisions (not just be reported), use this lightweight monthly cadence:

Report operating margin and the two drivers

- gross margin

- OpEx percent of revenue (R&D, S&M, G&A split)

Explain variance vs last month and vs plan

- mix changes (plan mix, channel mix, segment mix)

- headcount and compensation changes

- one-time expenses

Decide one action per driver

- Gross margin action (vendor, infra, support load)

- OpEx action (hiring plan, role clarity, tooling consolidation)

- Revenue action (pricing, packaging, retention focus)

A driver tree turns operating margin from a single number into specific levers: gross margin improvement and OpEx ratio control.

The bottom line

Operating margin is the clearest scoreboard for whether your SaaS revenue is starting to fund the business. Use it to pace hiring, sanity-check go-to-market efficiency, and communicate operating leverage. But don't let it become a vanity metric: always explain why it moved, and validate that the improvement is durable by pairing it with retention, payback, and cash metrics.

Frequently asked questions

It depends on stage. Early-stage SaaS is often negative because hiring leads revenue. Mid-stage companies targeting efficient growth often aim for breakeven to 10 percent. At scale, strong SaaS businesses commonly reach 15 to 30 percent. Compare against your growth rate using Rule of 40, not margin alone.

Use recognized revenue from your P and L for true operating margin. ARR is useful for planning, but it can diverge from revenue because of implementation timing, usage revenue, and accounting recognition. If you must use ARR as a proxy, be consistent and label it clearly to avoid confusing profitability with bookings momentum.

The most common causes are faster OpEx growth than revenue, lower gross margin due to higher hosting or support costs, or a mix shift toward lower-margin plans or channels. Also check one-time items like severance or legal fees. Analyze margin as gross margin minus OpEx percent to isolate the driver.

Include founder salary in operating expenses if it is a real ongoing cost; otherwise your margin will be overstated and hiring plans will break later. Stock-based compensation is often excluded in non-GAAP presentations, but it is still a real cost to owners. Track both GAAP and a clearly defined adjusted margin.

Use it to set hiring pace, decide whether price increases are funding growth or just masking inefficiency, and determine how much go-to-market spend you can sustain without worsening burn. Pair it with Burn Multiple and CAC Payback Period to ensure improving margin is coming from durable unit economics, not short-term cuts.