Table of contents

Lead velocity rate (LVR)

Founders feel "pipeline pain" months before the P&L shows it: a weak flow of qualified leads today turns into missed bookings and stalled ARR later. Lead Velocity Rate (LVR) is one of the fastest ways to see that problem early—and decide whether you need to fix demand generation, qualification, or sales capacity.

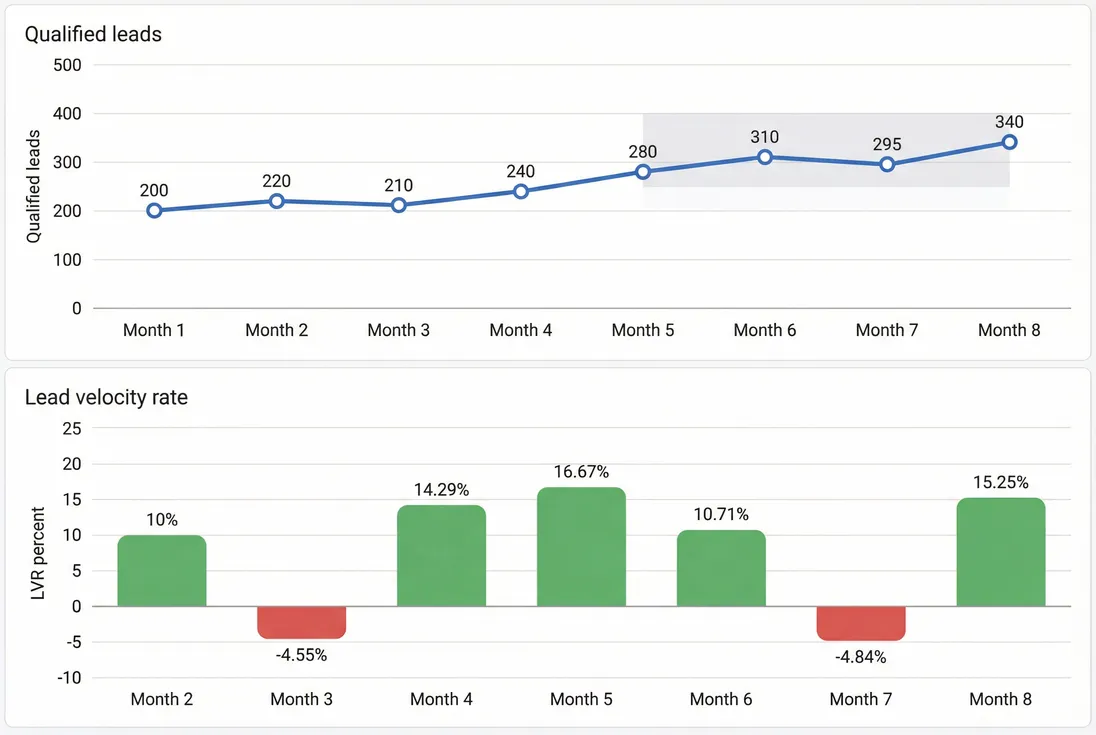

Lead Velocity Rate (LVR) is the month-over-month percentage growth in your count of qualified leads. The word "qualified" matters: LVR is only useful when it tracks the lead stage that reliably turns into revenue in your motion.

Qualified lead volume shows the trend; LVR shows the acceleration (or slowdown) month to month—often the earliest warning sign of a future bookings miss.

What LVR reveals

LVR answers a practical question: Is our future pipeline supply expanding fast enough to support our growth plan? Because leads take time to convert, LVR is a leading indicator for bookings—especially when you pair it with your sales cycle and conversion rates.

LVR is most valuable for:

- Detecting demand shortfalls early. If qualified leads stop growing, your future closed-won volume usually follows.

- Separating "more activity" from "more momentum." You can be busy (emails, calls, content) while qualified demand is flat.

- Checking whether growth is repeatable. A one-time spike (conference, partner drop) can inflate one month; sustained LVR is the signal.

LVR does not tell you:

- Whether leads are good (you need downstream conversion like Win Rate and stage conversion).

- Whether your revenue engine is healthy overall (you also need retention metrics like NRR (Net Revenue Retention) and GRR (Gross Revenue Retention)).

- Whether spend is efficient (pair with CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost) and CPL (Cost Per Lead)).

The Founder's perspective

If LVR is slowing, you're usually looking at a decision point: accept a slower growth plan, increase investment (paid, outbound, partners), or change the motion (targeting, packaging, conversion work). Waiting for revenue to confirm the trend is how teams lose two quarters.

How to calculate LVR

At its simplest, LVR is the percentage change in qualified lead count from last month to this month.

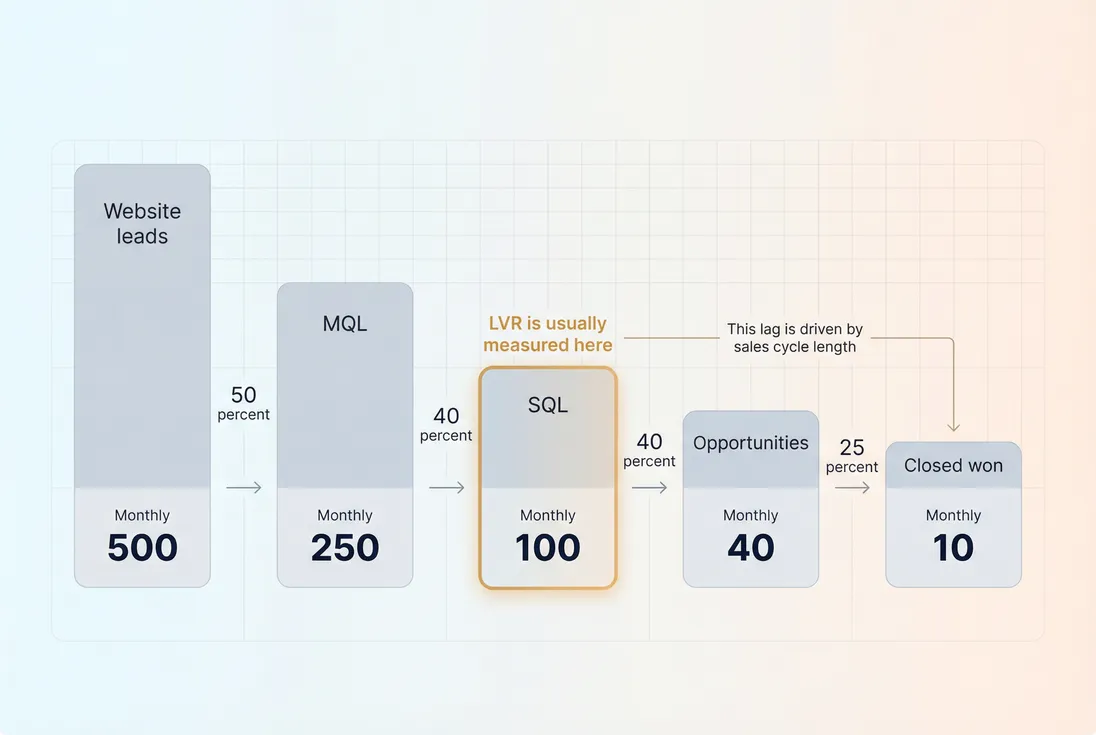

Choose the right "qualified" stage

The biggest mistake is calculating LVR on a lead stage that doesn't predict revenue.

Common choices:

- MQL velocity (marketing-qualified leads): best when marketing qualification strongly correlates with pipeline creation.

- SQL velocity (sales-qualified leads): often best in sales-led motions where sales confirmation is the real gate.

- Opportunity velocity: can be best for enterprise if opportunity creation is consistent and tightly defined.

- Product-qualified lead velocity: useful in PLG when product signals are the qualification gate.

If you're unsure, pick the stage that is closest to revenue but still has enough volume to be stable. Many teams land on SQL.

You'll also want LVR to align with how you think about pipeline, such as your definition of Qualified Pipeline. If your "qualified lead" definition is loose, LVR becomes a vanity trend.

A quick example

- Last month SQLs: 200

- This month SQLs: 240

Interpretation: your supply of qualified leads grew 20% month over month. If win rate and sales cycle stay stable, bookings should rise in the following months.

Use a trailing average to reduce noise

LVR is inherently jumpy, especially with smaller volumes. Many founders look at the raw LVR and a trailing average (for example, a trailing 3-month average). See T3MA (Trailing 3-Month Average) for smoothing logic you can apply to almost any growth metric.

One simple approach is to compute LVR monthly, then average the last three values. The goal isn't statistical perfection; it's avoiding overreacting to a single weird month (seasonality, a campaign ending, a CRM cleanup).

Data rules that prevent bad LVR

LVR is only as trustworthy as your counting rules. Set these explicitly:

- Count unique leads or accounts. Avoid duplicates and merges inflating volume.

- Use the same time cut. For example: leads that became SQL during the month, not leads that exist as SQL at month-end (those are different).

- Freeze the definition. Changing scoring thresholds or acceptance rules will change LVR even if demand is constant.

LVR is best measured at the stage that predicts revenue; downstream conversion and sales cycle explain why LVR can improve before bookings move.

What drives LVR

LVR goes up when you create more qualified leads this month than last month. That sounds obvious, but the "why" usually falls into a handful of operational levers.

Top-of-funnel supply

More impressions, clicks, outbound touches, partner referrals, events, and so on can increase qualified leads—but only if targeting stays tight.

A common failure mode: you raise spend and LVR rises, but it's coming from low-fit segments that don't convert. That's why LVR must be paired with downstream rates like Conversion Rate and Win Rate.

Qualification rate

You can increase qualified leads without increasing raw leads by improving the rate at which leads become qualified:

- Better lead scoring or routing

- Faster speed-to-lead

- Clearer ICP targeting and messaging

- Higher-intent offers (demo vs newsletter)

- Better SDR discovery and disqualification

This is also where definitions can accidentally "juice" LVR. If sales starts accepting more leads as SQL (lowering the bar), LVR improves—but your opportunity conversion or win rate will often drop.

Channel mix shifts

LVR can change simply because the mix changes:

- Outbound tends to create more "sales-driven" SQLs (higher control, sometimes lower conversion).

- Paid search may scale quickly but saturate.

- Partners can cause step-function increases that don't repeat monthly.

When LVR changes, always ask: Is this broad-based across channels, or one channel moving the whole number?

Sales capacity and handoffs

If SDR or AE capacity is constrained, qualified leads may stall even if demand exists. The symptom looks like "marketing is down," but the root cause is operational:

- Response times increase

- Meetings aren't booked

- Leads aren't worked

- Qualification events don't happen inside the month

Pair LVR with operational checks like meeting set rate and time-to-first-touch. If you sell with a longer motion, also watch Sales Cycle Length: longer cycles can make LVR look "fine" while bookings slip out.

Seasonality and calendar effects

Many SaaS categories have predictable patterns (holidays, budget cycles, summer slowdowns). LVR can dip seasonally without indicating a broken machine. That's another reason to use trailing averages and year-over-year comparisons when possible.

The Founder's perspective

A single-month LVR drop is a question. Two to three months of slowing LVR is a plan change. Either you invest to reverse it, or you proactively reset targets so you don't end up doing emergency cuts after the miss hits revenue.

How founders use LVR in decisions

LVR becomes actionable when you translate it into "Are we on track for our growth plan?" and "What do we do if we aren't?"

Set targets from revenue, not vibes

Start from your growth target and work backward.

A basic planning chain looks like:

- New customer target (or new ARR target)

- Lead-to-customer rate (from SQL to closed-won)

- Required qualified leads

Then compare required qualified leads to your current qualified lead volume to determine the LVR you need.

Here's a simple example:

- Next month target: 30 new customers

- Historical SQL-to-customer rate: 15%

- Required SQLs: 30 / 0.15 = 200 SQLs

If last month you produced 175 SQLs, you need:

- (200 − 175) / 175 = 14.3% LVR

This planning style prevents a common founder trap: expecting revenue to grow faster than the top of the funnel can support.

Pair LVR with three guardrails

LVR tells you lead quantity momentum. To make decisions, pair it with:

- Win rate: see Win Rate. If LVR rises but win rate falls, you might be scaling low-fit demand.

- Sales cycle length: see Sales Cycle Length. If cycles lengthen, revenue will lag even with strong LVR.

- Deal size trend: for deal-led motions, monitor ASP (Average Selling Price) or ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account). Smaller deals can hide behind stable lead flow.

Use LVR to time hiring

Hiring SDRs or AEs is often the biggest "irreversible" spend decision a founder makes. LVR helps avoid hiring into a demand trough.

A practical rule: If LVR has been negative or flat for 2–3 months at the qualified stage, be cautious about adding quota capacity unless you have a clear demand unlock already in motion.

Conversely, if LVR is consistently strong and downstream conversion is stable, hiring ahead of revenue can be rational—because the leads are already arriving.

Benchmarks that actually help

There's no universal "good" LVR. But ranges can be a sanity check.

| Company context | Typical monthly LVR range | What it implies |

|---|---|---|

| Early-stage, finding traction | 10% to 30% | High volatility; validate quality with win rate |

| Scaling SMB mid-market | 5% to 15% | Repeatable demand engine; watch efficiency |

| Enterprise, longer cycles | 3% to 10% | Often opportunity-based; lag is longer |

| Any stage | Negative | Pipeline supply contracting; investigate fast |

If you're aiming for aggressive ARR growth, make sure the implied LVR is plausible given your channels and capacity. If not, your plan is internally inconsistent.

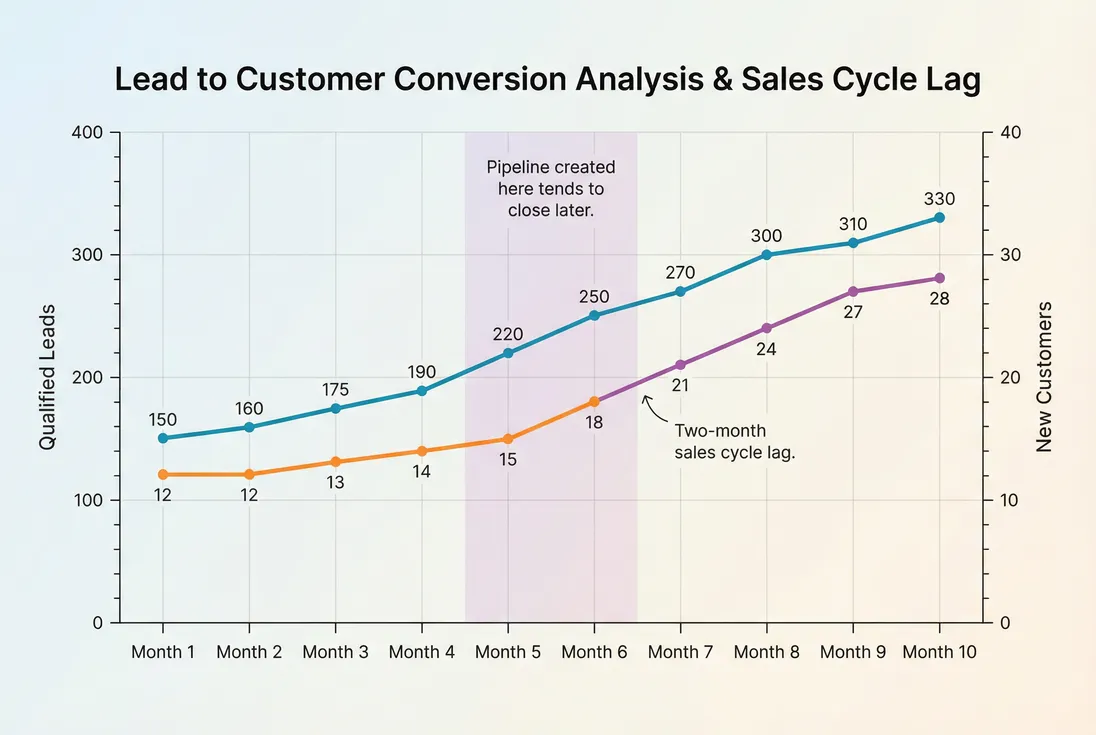

Understand the lag to revenue

Even perfect LVR doesn't instantly show up in revenue. The delay is your sales cycle.

LVR moves before bookings because qualified leads created now convert later; the lag length is largely your sales cycle.

If you don't explicitly account for lag, you'll make bad calls like cutting spend right after a lead dip (which guarantees a revenue dip later) or hiring AEs because last month's bookings were strong (even though lead supply is slowing now).

When LVR misleads

LVR is simple—which makes it easy to corrupt unintentionally. These are the scenarios where it "breaks" and how to protect against them.

Qualification drift

If "qualified" becomes easier (or harder), LVR changes even if demand is flat.

How to catch it: track step conversion rates between stages. If SQL volume rises but opportunity conversion or win rate drops, you likely loosened qualification. Use Churn Reason Analysis logic as an analogy: you need consistent categorization rules, or trends become fiction.

Small denominators

If last month had 15 qualified leads and this month has 25, LVR is 67%. That sounds amazing, but it may be noise.

How to handle it: use a trailing average and focus on absolute counts alongside percentages. Also consider weekly tracking for operations, but judge performance on monthly or trailing views.

Channel mix whiplash

One partner email can spike leads and inflate LVR; next month normalizes and LVR looks "bad." That's not a performance collapse—it's a mix artifact.

How to handle it: compute LVR by channel and by segment (ICP vs non-ICP). If you don't segment, LVR becomes a blended number that's hard to act on.

CRM and attribution artifacts

Backfills, imports, deduping projects, or lifecycle automation changes can create fake growth (or fake declines).

How to handle it: maintain a change log of system changes and annotate your trend reviews. If you can't explain a step-change with a real-world event, assume data process before performance.

It ignores efficiency

You can buy LVR with spend. That's not inherently wrong, but it can quietly destroy unit economics.

How to handle it: always pair LVR with efficiency metrics like CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost) and CAC Payback Period. Strong LVR with collapsing payback is not a win—it's a burn decision.

The Founder's perspective

LVR is a steering wheel, not a speedometer. It helps you turn earlier—before revenue changes. But if you steer using only LVR, you can drive straight into low-quality demand or uneconomic growth. Use LVR to spot momentum changes, then validate with conversion, cycle length, and CAC.

If you run a SaaS business where revenue depends on a sales pipeline, LVR is one of the highest-leverage "early warning" metrics you can track. Define "qualified" once, calculate it consistently, smooth it enough to avoid noise, and always interpret it alongside conversion, sales cycle, and unit economics. That combination turns LVR from a vanity trend into an operating signal.

Frequently asked questions

A good LVR depends on stage and motion. Early-stage teams often aim for 10 to 30 percent month over month growth in qualified leads, while scaled teams might target 3 to 10 percent. Use your sales cycle length and win rate to back into the LVR needed to hit ARR targets.

Calculate LVR on the stage that best predicts revenue in your business. For sales-led SaaS, SQL or sales accepted lead velocity is usually more meaningful than MQL velocity. For enterprise, opportunity velocity can be best. The key is consistency in definition and a stable handoff rule.

It usually means quality or conversion is down, or the impact has not hit revenue yet due to sales cycle lag. Check win rate, sales cycle length, and average deal size. Also verify you did not loosen qualification standards. LVR is a leading indicator, not same-month revenue.

Start with the new customer or new ARR target, then divide by your lead-to-customer rate to get required qualified leads. Compare that to your current qualified lead volume to compute the needed month over month increase. Revisit monthly as win rate, ASP, and sales cycle change.

The biggest traps are changing what counts as qualified, double-counting duplicates, and mixing channels with very different conversion rates. Seasonality and small denominators also create noisy swings. Add guardrails: track win rate, pipeline stage conversion, and a trailing 3-month average for LVR.