Table of contents

Lead conversion rate

Founders usually don't run out of "growth ideas." They run out of efficient growth. Lead conversion rate is one of the fastest ways to see whether adding more leads will produce more revenue—or just more noise, more sales load, and higher CAC.

Lead conversion rate is the percentage of leads that convert into your chosen outcome (most commonly a paying customer) within a defined period and definition set. The definition part matters more than the math: if you change what counts as a "lead" or what counts as "converted," the metric will move even if the business didn't.

What you're really measuring

At its core, lead conversion rate is a "funnel integrity" metric. It answers: When we put a lead into our system, what fraction becomes revenue-producing customers?

The catch: SaaS teams use the word "lead" to mean different things:

- A website form fill

- A free trial signup

- A booked demo request

- A marketing qualified lead (MQL (Marketing Qualified Lead))

- A sales qualified lead (SQL (Sales Qualified Lead))

And "conversion" can mean different endpoints:

- Trial started

- Demo held

- Opportunity created

- New customer (paid subscription)

- Activated customer (paid + reached product value)

You'll get the most decision value when you choose one primary definition (lead → new customer) and then track stage conversions to diagnose where changes come from.

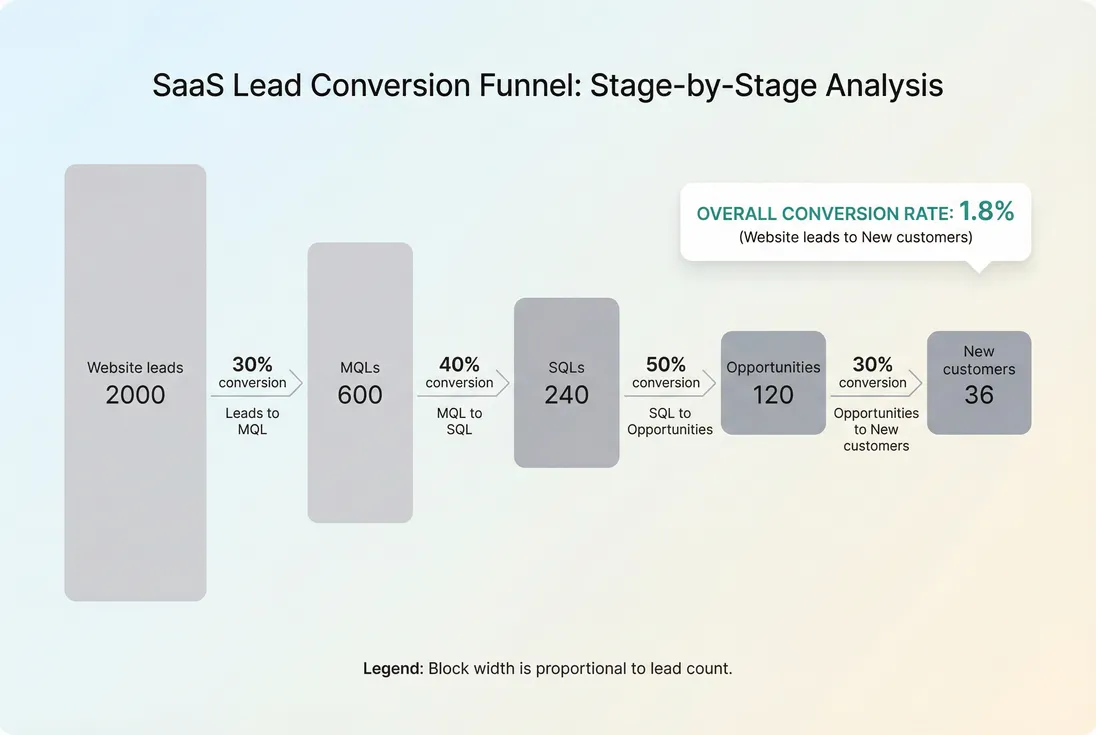

A simple funnel makes it obvious whether a lead conversion problem is top-of-funnel quality or later-stage sales execution.

Lead conversion rate vs. win rate

Don't confuse lead conversion rate with Win Rate:

- Lead conversion rate includes everything from lead creation through qualification and sales.

- Win rate typically starts later (opportunity → closed-won).

If your lead conversion rate falls but win rate stays flat, you likely have a quality/qualification issue. If win rate falls, it's more likely sales execution, pricing, or competitive pressure.

How to calculate it (without fooling yourself)

The arithmetic is simple; the time logic is not.

Where teams get into trouble is choosing numerator and denominator from different "time realities." There are two common approaches:

1) Period-based (easy, often misleading)

Example: "In September we got 40 new customers and created 2,000 leads, so conversion is 2%."

This breaks when your Sales Cycle Length is longer than the reporting period or changes meaningfully. A strong September lead cohort might not close until October or November.

Use period-based numbers mainly for fast-cycle motions (self-serve, short sales cycles) or as a rough operational pulse.

2) Cohort-based (recommended)

Cohort-based conversion answers: Of the leads created in a period, what percent converted within a fixed window?

Practical way to implement:

- Pick a cohort unit (usually lead created month).

- Pick a conversion window that matches reality (often 30, 60, or 90 days).

- Attribute each new customer back to the lead cohort that sourced it.

- Track conversion by cohort over time.

If you haven't done cohorting before, the mental model is the same as Cohort Analysis: you're separating "what happened this month" from "how good this month's inputs were."

The Founder's perspective

If your sales cycle is 45–90 days, period-based lead conversion will make you overreact. Cohort-based conversion lets you decide whether to change targeting, fix a funnel step, or simply wait for a healthy cohort to mature.

The minimum definition set you need

Write these down in your metric spec:

- Lead definition: what event creates a lead (and what's excluded).

- Conversion definition: what event counts as "converted" (paid subscription date, first invoice paid, etc.).

- Window and timestamp: lead created date vs conversion date, and the allowed time window.

- De-duplication rule: what happens if the same person submits twice.

- Recycled leads: do you count reactivated old leads as new leads?

These choices often move the metric more than your actual growth work.

What moves the metric in real SaaS funnels

Lead conversion rate is an output of three systems working together:

- Acquisition quality (who you're attracting)

- Qualification and sales process (how you handle demand)

- Offer and product fit (what happens when they try to buy and use)

Here are the highest-leverage drivers founders should watch.

Channel mix and targeting

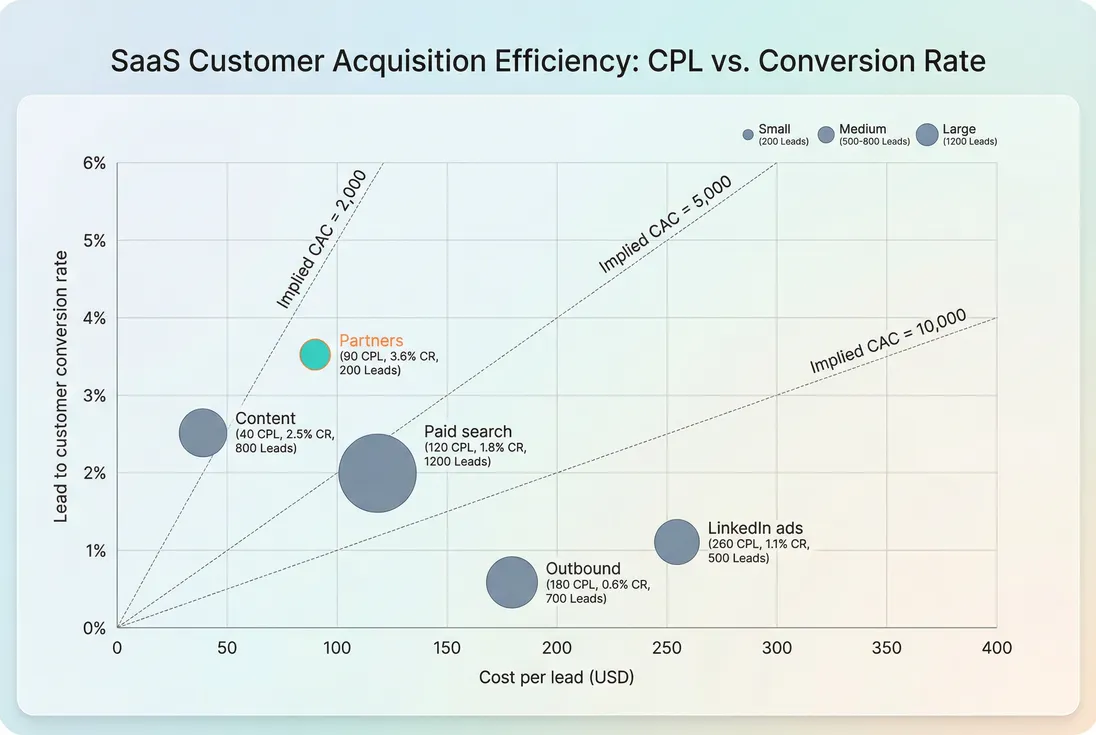

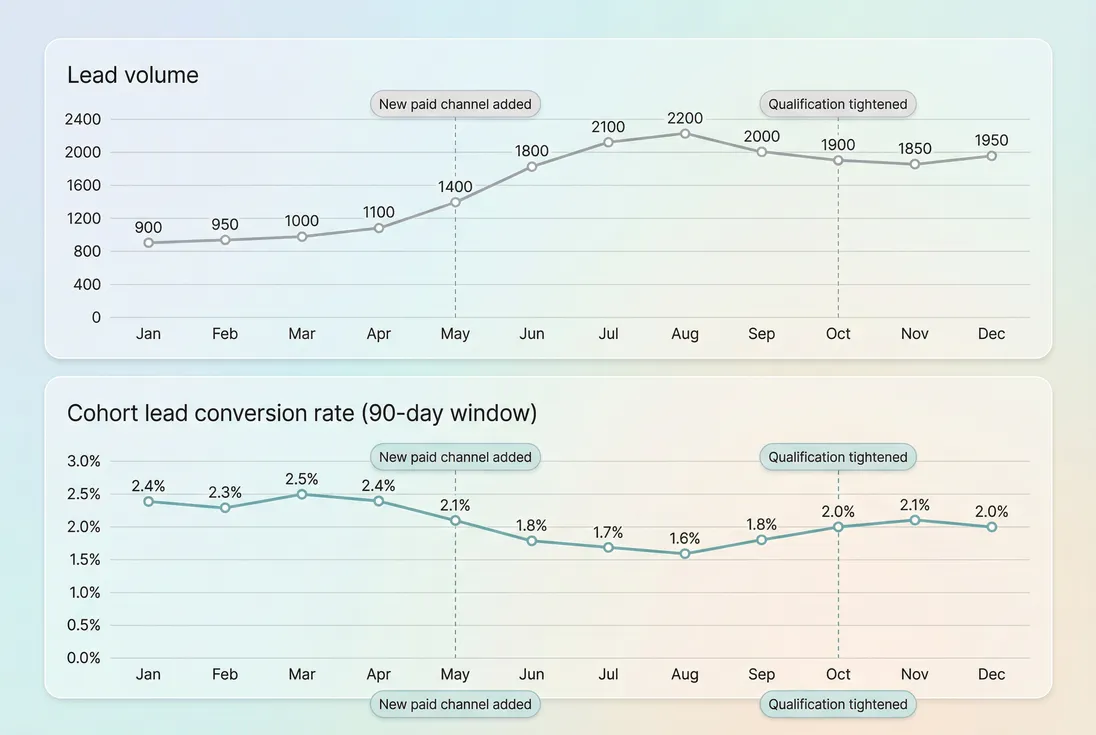

Your blended lead conversion rate is a weighted average. If you add a new channel that produces many low-intent leads, conversion can drop even if your "core" channels are stable.

This is why you should always segment by:

- Source channel (paid search, outbound, partners, content)

- Persona / industry

- Company size

- Geography (if relevant)

Pair this analysis with CPL (Cost Per Lead) so you don't optimize conversion while ignoring economics.

Conversion rate only matters in context: CPL and conversion together determine the implied CAC of each lead source.

Qualification thresholds (MQL/SQL)

If you tighten qualification, your lead conversion rate can rise simply because you excluded low-quality leads. That can be good—if it's intentional—but it changes what the metric means.

A practical approach:

- Track lead → MQL and MQL → SQL (using MQL (Marketing Qualified Lead) and SQL (Sales Qualified Lead)) to see whether your team is changing the bar.

- Track SQL → customer to evaluate sales effectiveness.

If only the early-stage conversions change, you likely adjusted targeting or definitions. If late-stage changes, you likely changed the offer, pricing, or sales execution.

Speed to lead and follow-up capacity

Lead conversion often collapses when volume rises faster than follow-up capacity. Common pattern:

- More leads from a new campaign

- Same SDR/AE capacity

- Slower response time

- Lower meeting rate

- Lower conversion

If your sales motion is human-assisted, treat lead conversion rate as a capacity planning signal, not just a marketing KPI.

Offer structure and pricing

Pricing changes can move lead conversion rate quickly—sometimes for good reasons.

- Raising price or removing discounts typically lowers conversion but can increase overall efficiency if ASP (Average Selling Price) rises enough.

- Adding annual prepay can reduce conversions while improving cash flow and sometimes retention.

Don't evaluate lead conversion rate alone. Tie it to downstream metrics like ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account), MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue), or ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue).

Product activation (especially PLG)

In self-serve or trial-heavy motions, lead conversion rate is often a proxy for "did the product deliver value fast enough?"

If you have a free trial, the biggest levers are usually:

- Time to first meaningful outcome (Time to Value (TTV))

- Onboarding completion (Onboarding Completion Rate)

- Early feature usage (Feature Adoption Rate)

A "marketing problem" might actually be an onboarding problem.

How to interpret changes (and avoid false signals)

A lead conversion rate change is only actionable if you can answer: What changed, and where in the funnel did it change?

Start with these three checks

Did the lead definition change?

New forms, new tracking rules, spam filtering, deduping, or a new enrichment provider can shift leads dramatically.Did the channel mix change?

A higher share of top-of-funnel leads (e.g., webinar signups) can drop conversion even if core intent channels are stable.Is it a timing issue?

If sales cycle length increased, recent cohorts will look worse until they mature. This is why cohort windows matter.

Watch sample size and "denominator games"

When lead volume is low, conversion rate swings are normal. Don't overhaul your GTM based on a change from 2 customers to 3 customers.

A simple sanity check is to always look at:

- Lead count

- Converted customer count

- Conversion rate

Rates without counts create bad decisions.

Pair lead volume with cohort-based conversion to see whether growth initiatives increased demand efficiently or diluted lead quality.

The Founder's perspective

A conversion drop during a lead volume spike is not automatically "bad marketing." It can be a predictable outcome of expanding into colder channels. The question is whether the resulting CAC still works—and whether sales capacity and product activation can catch up.

Benchmarks and targets (useful, but conditional)

Benchmarks only matter if you align on the same definition: lead → paying customer within a fixed window.

Here are directional ranges founders can use to sanity-check performance:

| Motion / lead type | Typical lead → customer conversion |

|---|---|

| PLG/self-serve (website lead or signup → paid) | 0.5%–3% |

| SMB sales-assisted inbound | 1%–5% |

| Outbound lead (cold) → customer | 0.2%–2% |

| Midmarket sales-led inbound | 0.3%–1.5% |

| Enterprise (true enterprise buying) | 0.05%–0.5% |

What matters more than the range is your trend by channel and persona. A "good" overall conversion can hide a brittle funnel if one channel is carrying everything.

If you want a tighter operational target, work backward from economics:

- What CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost) can you afford?

- What LTV (Customer Lifetime Value) and CAC Payback Period do you need to hit?

- Given your CPL and sales cost, what conversion must you maintain?

How founders use it to make decisions

Lead conversion rate becomes powerful when you use it as an input to planning, not just a report card.

1) Translate marketing spend into CAC reality

If you know your CPL and lead conversion rate, you can estimate the implied CAC from that channel (before adding sales and onboarding costs):

Example:

- CPL = $150

- Lead conversion rate = 1.5% (0.015)

Implied CAC from leads ≈ $150 / 0.015 = $10,000

If your target CAC is $7,000, you either need cheaper leads, higher conversion, higher price (ASP (Average Selling Price)), or a different segment.

The Founder's perspective

When a channel "scales" but conversion degrades, teams often celebrate the lead graph and miss the economics. Converting CPL into implied CAC forces a grown-up conversation: do we fund this channel, fix the funnel, or stop?

2) Decide whether to hire sales or fix upstream

A common fork in the road:

- If lead conversion drops because follow-up capacity is saturated, hiring (or improving routing) can restore conversion quickly.

- If lead conversion drops because lead quality diluted, hiring sales usually just increases cost. Fix targeting, messaging, and qualification first.

Your best diagnostic is stage conversion:

- Lead → MQL down: targeting/messaging/channel issue

- MQL → SQL down: qualification issue (or ICP mismatch)

- SQL → customer down: sales execution, pricing, competition, or product gaps

3) Make pricing and packaging tradeoffs explicit

Pricing and packaging changes should be evaluated as a system:

- Conversion rate might fall

- ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account) or ASP (Average Selling Price) might rise

- Net effect on ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue) per lead might improve

A simple "reality check" question: Are we earning more ARR per lead cohort after the change, or just filtering out buyers?

4) Forecast new customer volume from lead velocity

Forecasting becomes straightforward when you connect:

- Lead growth rate (Lead Velocity Rate (LVR))

- Lead conversion rate (cohort-based)

- Sales cycle timing

Even if your finance model is lightweight, this relationship helps you answer: If we add 500 leads per month, how many customers will that actually produce in 60–90 days?

5) Know when to optimize conversion vs. expand top-of-funnel

A practical decision rule founders can use:

- If conversion is unstable by cohort, don't scale lead volume yet. Fix the funnel leak.

- If conversion is stable and CAC is inside guardrails, scale lead volume.

- If conversion is stable but CAC is high, work on CPL and/or pricing (often faster than trying to squeeze conversion further).

This connects directly to capital efficiency metrics like Burn Multiple and Capital Efficiency: poor conversion silently destroys efficiency.

Common failure modes (and how to prevent them)

A few patterns repeatedly make lead conversion rate "look" worse or better than reality:

Mixing recycled leads into new leads

If old leads re-enter the funnel (new form fill, re-engagement campaign), decide whether they are:

- A new lead (counts in denominator), or

- A reactivation workflow (tracked separately)

Be consistent, or your trend line becomes meaningless.

Counting accounts vs. people inconsistently

In B2B SaaS, decide whether the metric is:

- Person-level conversion (contact → customer account), or

- Account-level conversion (account lead → customer account)

If outbound is account-based and inbound is contact-based, blending them is misleading. Segment them.

Letting attribution drive the story

Lead conversion rate is not an attribution model. If you use last-touch attribution, you will over-credit late-stage channels (retargeting, branded search). Use lead conversion rate primarily to measure funnel throughput, then apply attribution carefully as a separate layer.

Optimizing the metric instead of the business

It's easy to increase conversion by narrowing your lead definition so only high-intent requests count. That can be correct—but only if revenue and pipeline health hold up.

Cross-check with:

A simple operating cadence

If you want lead conversion rate to drive real action, keep the cadence lightweight:

- Weekly: stage conversion checkpoints (lead → meeting, meeting → SQL, SQL → opportunity)

- Monthly: cohort lead conversion rate by source and segment

- Quarterly: revisit lead and conversion definitions, and ensure they still match the business

The goal isn't a perfect metric. It's a stable metric that reliably tells you whether growth inputs are turning into customers—and what to fix when they don't.

Frequently asked questions

It depends on your funnel definition and sales motion. For inbound, sales-assisted SMB SaaS, lead to customer is often 1 to 5 percent. Midmarket is commonly 0.3 to 1.5 percent. Enterprise can be below 0.5 percent. The only useful benchmark is your own trend by channel and segment.

Use a cohort view for decision-making: leads created in a period divided into customers generated from that cohort within a fixed window like 60 or 90 days. Month-closed divided by month-created can be badly misleading when sales cycle length changes or pipeline speeds up or slows down.

Split the funnel into stages and segment by source and persona. If MQL to SQL drops, targeting or qualification is likely off. If SQL to customer drops, sales process, pricing, or competition is the culprit. Also check speed-to-lead and meeting show rates before changing acquisition spend.

Conversion rate is the denominator in customer acquisition economics. If your cost per lead stays flat but conversion falls from 2 percent to 1 percent, the implied CAC from that channel doubles. That typically lengthens CAC payback and can break your growth plan even when lead volume looks strong.

Optimize conversion when you have sales capacity, healthy lead volume, and obvious stage leakage like low demo set rate or poor trial activation. Buy more leads when your funnel is stable, conversion is consistent by cohort, and your CAC and payback targets are safely inside your guardrails for LTV and cash runway.