Table of contents

Gross margin

Gross margin is one of the fastest ways to tell whether your growth is compounding into profit—or quietly compounding delivery costs that will squeeze you later. If you don't know your gross margin (and what's driving it), you can't set sustainable pricing, hire responsibly, or trust your payback math.

Gross margin is the percentage of revenue left after paying the direct costs to deliver your product or service (COGS). What remains is gross profit—the pool that funds sales, marketing, R&D, and G&A.

What gross margin reveals

Gross margin answers a simple operational question: when you add one more dollar of revenue, how many cents are left after delivering the service?

That sounds basic, but founders use it to make high-leverage decisions:

- Pricing sanity checks: If your gross margin is thin, you have less room for aggressive pricing, discounting, and channel fees.

- Customer quality control: Some "great" customers are unprofitable because they consume disproportionate support, onboarding, or infrastructure.

- Scaling confidence: High gross margin gives you more flexibility to invest in growth and survive volatility.

- Unit economics integrity: Metrics like LTV (Customer Lifetime Value) and CAC Payback Period are materially different when computed on gross profit versus revenue.

The Founder's perspective

If gross margin is unclear, you'll over-hire, under-price, and misread payback. If gross margin is stable and improving, you can spend on growth with a much tighter grip on downside risk.

Gross margin also acts as an early warning system. Many SaaS businesses don't "suddenly" become inefficient—margin erodes gradually due to infrastructure creep, support load, and discounting that compounds with scale.

How to calculate it

Gross margin is typically calculated from recognized revenue and cost of goods sold (COGS). If you're mixing cash-basis revenue with accrual-basis costs, your margin will swing for accounting reasons rather than business reasons. If you need a refresher on revenue definitions, see Recognized Revenue.

The core formulas:

Two practical rules for founders:

- Track both percent and dollars. A "great" margin percent on small revenue can still mean not enough gross profit dollars to fund a team. Conversely, a modest margin percent on large revenue can throw off significant gross profit.

- Be consistent about revenue presentation. If you report revenue net of refunds/credits one month and gross the next, margin becomes noise. For policy considerations, see Refunds in SaaS and Discounts in SaaS.

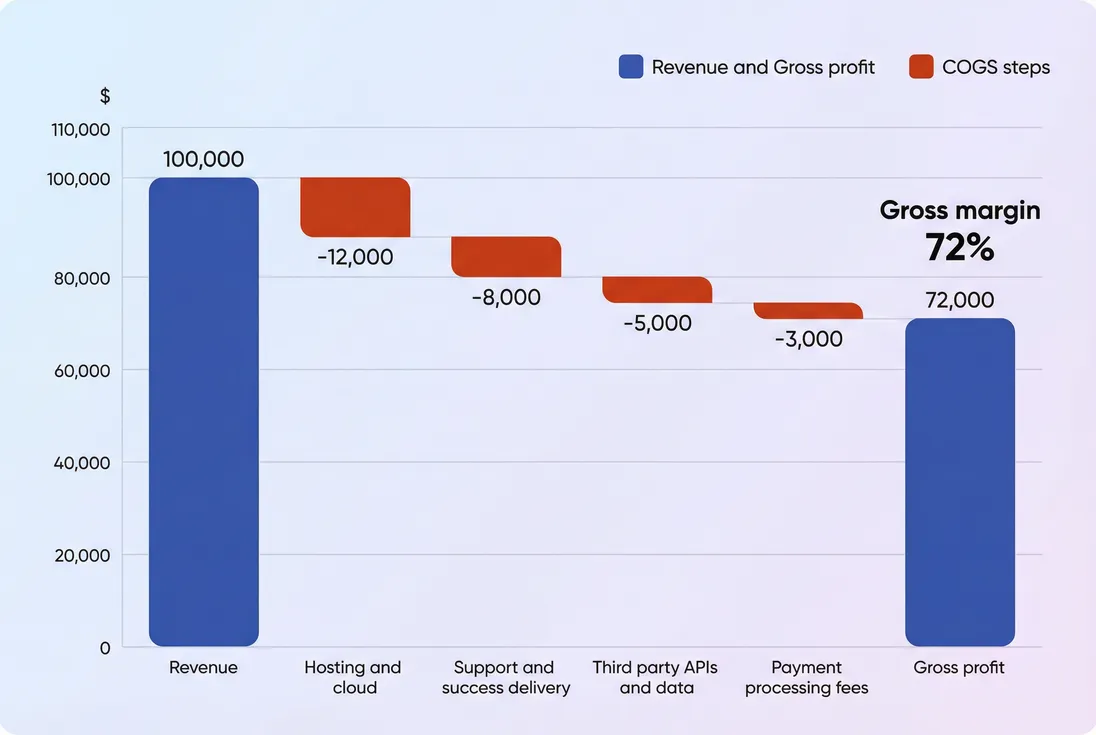

A quick example

If you recognize $200,000 of revenue in a month and delivery costs are $50,000:

- Gross profit = $150,000

- Gross margin = 75%

If revenue grows to $240,000 but delivery costs grow to $80,000, gross margin drops to 66.7%—even though revenue increased. That's the point: gross margin tells you whether growth is getting more expensive to deliver.

What belongs in COGS (for SaaS)

Most gross margin confusion comes from one place: what you put in COGS. For software, COGS should represent the costs required to run and support the product for customers.

A good working definition:

COGS includes costs that are (a) necessary to deliver the service and (b) scale meaningfully with customers, usage, or revenue.

For deeper accounting context, see COGS (Cost of Goods Sold).

Common SaaS COGS categories

Typical inclusions:

- Hosting and cloud infrastructure: compute, storage, bandwidth, CDN, observability tied to production

- Third-party services used in delivery: email/SMS sending, maps, AI inference APIs, data providers

- Payment processing and billing fees: often treated as COGS because they scale with revenue (see Billing Fees)

- Frontline support and delivery: support agents, on-call rotations, incident response

- Customer onboarding and implementation (if required): especially in enterprise or services-heavy motions

- SLA penalties or service credits (if material)

Usually excluded (operating expenses):

- Product development (R&D)

- Sales and marketing

- General admin and finance

- "Nice-to-have" CS programs not required to deliver service

The gray zone: support and customer success

Support and CS are where founders get inconsistent. A practical approach:

| Cost item | Often COGS? | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|

| Tier 1 support | Yes | Scales with customers; required to deliver service |

| Implementation for enterprise | Often yes | Direct delivery cost tied to a deal |

| CSMs managing renewals | Depends | If mostly retention delivery, many treat as COGS; if mostly expansion/sales assist, keep in S&M |

| CS leadership, enablement | No | More fixed/strategic than delivery |

The Founder's perspective

Don't obsess over perfect classification—obsess over consistent classification. Your goal is decision-grade trends: is delivery getting cheaper per dollar of revenue, or not?

Taxes, VAT, and "pass-through" items

If you collect and remit taxes (like VAT), your revenue reporting policy matters. Many teams treat taxes as pass-through and exclude them from revenue entirely. What's dangerous is mixing policies over time or across geographies. If VAT is a recurring complexity for you, see VAT handling for SaaS.

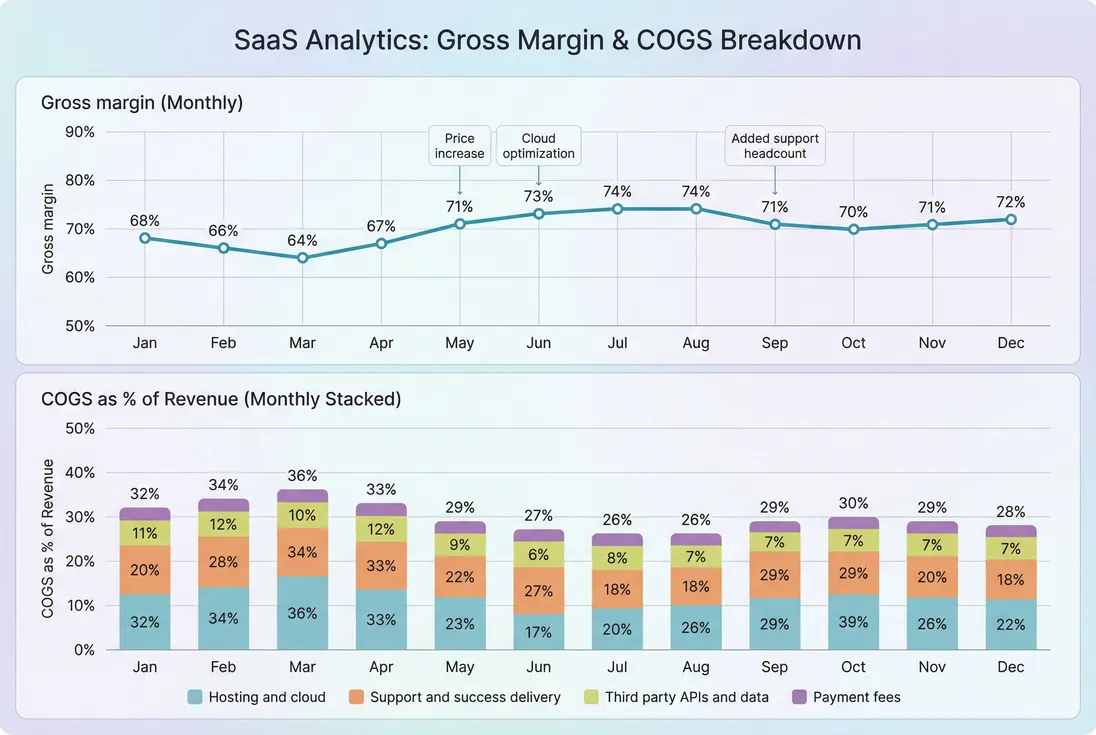

What drives gross margin up or down

Gross margin moves for only two reasons:

- Revenue per unit increases (price, packaging, mix shift to higher-margin customers)

- COGS per unit decreases (infrastructure efficiency, support efficiency, vendor renegotiation)

A helpful way to think about it:

So margin improves when COGS grows slower than revenue, and worsens when COGS grows faster than revenue.

The most common SaaS margin levers

Pricing and packaging (revenue-side)

- Price increases lift margin quickly when COGS is relatively fixed per account.

- Packaging can raise margin by charging for high-cost features (integrations, data exports, AI usage).

- Discounting can quietly destroy margin because COGS usually does not fall with price (see Discounts in SaaS).

Mix shift (revenue-side)

- Selling more to enterprise can increase ARPA but sometimes decrease margin if onboarding, support, and security requirements add delivery cost.

- A shift to usage-based pricing can stabilize margin if pricing tracks variable cost—but can compress margin if you undercharge for usage-heavy customers (see Usage-Based Pricing).

Infrastructure efficiency (cost-side)

- Cloud costs creep when you add features, data retention, observability, or redundancy without optimization.

- Vendor costs (data providers, API platforms) can become your "hidden COGS tax."

Support and service load (cost-side)

- If support tickets per account rise with new features, bugs, or poor onboarding, margin erodes.

- High-touch onboarding may be strategically correct—but you should measure it as a deliberate COGS investment, not a surprise.

A scenario founders run into

You raise price 15% across the board, but gross margin barely moves. Why?

- If a big share of COGS is variable (payment fees, usage-driven infrastructure, third-party API calls), costs rise with revenue or usage.

- If discounts expand in response to pricing changes, realized ARPA may not increase as expected (see ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account)).

The fix is not "watch gross margin harder." The fix is to instrument the drivers: realized price (after discounts), usage per account, support effort per account, and vendor costs per account.

How founders actually use gross margin

Gross margin is not just a finance metric. It directly shapes product, go-to-market, and hiring decisions.

1) Setting a pricing floor

A simple pricing discipline: know your gross profit per account.

If your ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account) is $200 per month and gross margin is 70%, you generate $140/month of gross profit per account. That gross profit must cover acquisition, overhead, and product investment.

This is how pricing connects to payback in real life: if you acquire customers for $1,400 CAC, you're looking at roughly 10 months just to recover CAC on gross profit—before paying for anything else.

2) Making CAC payback and LTV real

Founders often calculate payback on revenue because it's easy. But cash doesn't care about easy.

- If your margin is 85%, revenue-based and gross-profit-based payback are similar.

- If your margin is 55–65%, the difference is decisive—and can flip "good" payback into "dangerous" payback.

This is why gross margin should be part of your read on Burn Multiple and overall capital efficiency: low margin growth tends to be cash-hungry growth.

3) Deciding where to hire

A margin drop can justify hiring—but only if you understand why it dropped.

Examples:

- Margin falling due to support overload might justify hiring support and fixing onboarding/product issues that drive ticket volume.

- Margin falling due to cloud spend often shouldn't be "hire more engineers" by default; it may be a FinOps/architecture sprint with clear cost-per-unit targets.

The Founder's perspective

Hiring to "fix margin" is only rational if you can name the unit that got worse: cost per active account, cost per ticket, or cost per usage unit. Otherwise you're just adding fixed cost on top of variable cost.

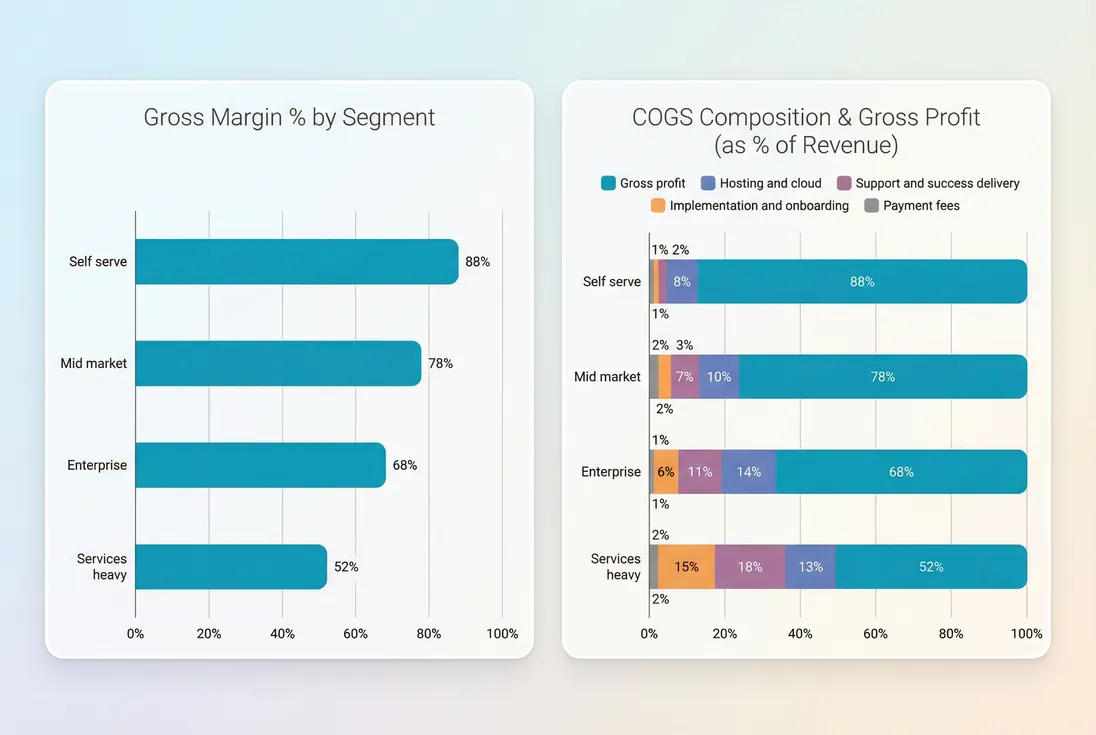

4) Choosing the right customers and motions

Two businesses can have the same top-line growth and very different futures because of margin by segment.

You want to know:

- Gross margin by plan (self-serve vs premium)

- Gross margin by segment (SMB vs mid-market vs enterprise)

- Gross margin by channel (direct vs partner, where fees may act like COGS)

- Gross margin by cohort (did newer customers get more expensive to serve?)

Even if your billing system doesn't provide cost allocation, you can still do directional segmentation by combining revenue segmentation (plans, customer attributes) with your best cost drivers (tickets, usage, onboarding hours). Cohort thinking helps here; see Cohort Analysis.

If you use GrowPanel for revenue analytics, you can segment revenue with filters and export customer lists via customer list to join with cost drivers from your support and cloud tooling.

Benchmarks and common red flags

Benchmarks are useful for direction, not validation. Your goal is to understand whether your margin structure matches your strategy.

Typical gross margin ranges (rule-of-thumb)

| SaaS model | Common gross margin range | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Self-serve, low-touch | 80–90% | Often minimal onboarding, efficient support |

| Mid-market, moderate touch | 70–85% | More CS, integrations, higher support load |

| Enterprise, high touch | 60–80% | Implementation and security requirements can weigh on COGS |

| Usage-based with costly infrastructure | 50–80% | Depends on pricing vs variable cost alignment |

| Services-heavy "SaaS + agency" | 30–70% | Services delivery can dominate COGS |

Red flags to take seriously

- Margin declines as you scale. This suggests you're accumulating delivery complexity faster than revenue quality improves.

- Margin volatility month to month. Often caused by inconsistent COGS treatment, refunds timing, or lumpy onboarding costs. Fix your definitions first.

- Enterprise growth lowers blended margin. That's not automatically bad—but it must be intentional and priced in (onboarding fees, higher ACV, longer retention).

- Discounting without margin awareness. A 20% discount can be far more than a 20% hit to gross profit if costs are largely fixed per account.

How to improve gross margin (without guesswork)

Gross margin improves fastest when you treat it like an operational metric with owners and drivers—not a quarterly finance output.

Step 1: lock a COGS policy

Write down:

- What goes into COGS (and what doesn't)

- How you treat refunds, credits, and chargebacks (see Refunds in SaaS)

- Whether billing fees are in COGS (see Billing Fees)

- Whether you report revenue net or gross of taxes (see VAT handling for SaaS)

Then don't change it casually. If you must change it, restate history so trends remain comparable.

Step 2: review a monthly margin bridge

Every month, produce a simple bridge like:

- Revenue

- Hosting and cloud

- Third-party vendors

- Support and CS delivery

- Payment fees

- Implementation/onboarding

- Gross profit and gross margin

Your goal is not accounting elegance. Your goal is: which lever moved?

Step 3: tie COGS to cost drivers

Pick 1–2 drivers per COGS bucket:

- Hosting: cost per active user, per workspace, per message, per gigabyte

- Support: tickets per customer, minutes per ticket, % escalations

- Vendors: cost per API call, per enrichment, per email/SMS

- Implementation: hours per deal, weeks to go-live

Once you have drivers, you can forecast margin under growth scenarios instead of hoping it stays stable.

Step 4: connect margin to product decisions

Margin is where product choices become financial reality:

- If a feature increases usage by 3x, do you charge for that usage?

- If a segment requires heavy onboarding, do you price onboarding separately, raise ACV, or streamline implementation?

- If support volume rises, do you fix root causes or accept lower margin?

This is also where gross margin relates to Contribution Margin: gross margin tells you the cost to deliver; contribution margin tells you what's left after other variable costs (often sales and marketing). Use both depending on the decision.

The Founder's perspective

Gross margin is the earliest place you can "feel" product and customer complexity turning into financial drag. When it slips, the best response is rarely a blanket cost cut—it's usually a pricing correction, a services boundary, or a delivery efficiency project with clear unit targets.

The bottom line

Gross margin is not a vanity percent. It's the economic engine of your SaaS model:

- It determines how much you can invest in growth without breaking payback.

- It exposes whether certain customers, plans, or motions are quietly unprofitable.

- It forces discipline around pricing, discounts, infrastructure, and delivery scope.

Track it consistently, break it into drivers, and review it like an operating metric—not a finance artifact.

Frequently asked questions

Many healthy SaaS businesses land in the 70 to 90 percent range, but the right target depends on your model. Self-serve software often runs higher, while enterprise with heavy onboarding or usage-based COGS can run lower. What matters most is trend, stability, and improving margin as you scale.

Put costs in COGS if they are required to deliver and retain the service and scale with customers, like frontline support and onboarding tied to active accounts. Keep strategic CS leadership, enablement, and broad retention programs in operating expenses. Consistency matters more than perfection, especially for trend comparisons.

Discounts reduce revenue, which can lower gross margin even if costs stay flat. Refunds and chargebacks should typically reduce revenue in the period they occur, not sit in COGS. Billing and payment processing fees are usually COGS because they scale directly with billed revenue. Apply one policy and stick to it.

Use gross margin to convert revenue into gross profit, which is what actually pays back acquisition costs. If your CAC payback period looks fine on revenue but weak on gross profit, you are buying low-quality or high-cost customers. LTV should generally be calculated on gross profit, not revenue.

The common culprits are mix shift and variable COGS. You may be selling more of a lower-margin plan, adding enterprise deals with heavy onboarding, or growing usage that increases cloud and third-party API costs faster than revenue. Break COGS into components and review margin by segment to pinpoint the driver.