Table of contents

Free cash flow (FCF)

When founders say "we're doing great" but can't make payroll without a new round, the problem is usually not revenue—it's cash generation. Free cash flow is the metric that tells you whether your growth is actually funding itself, or quietly increasing your dependence on outside capital.

Free cash flow (FCF) is the cash your business generates after paying to run the company and after required reinvestment in long-term assets. In plain terms: it's what's left over (or missing) once the month's real-world cash ins and outs settle.

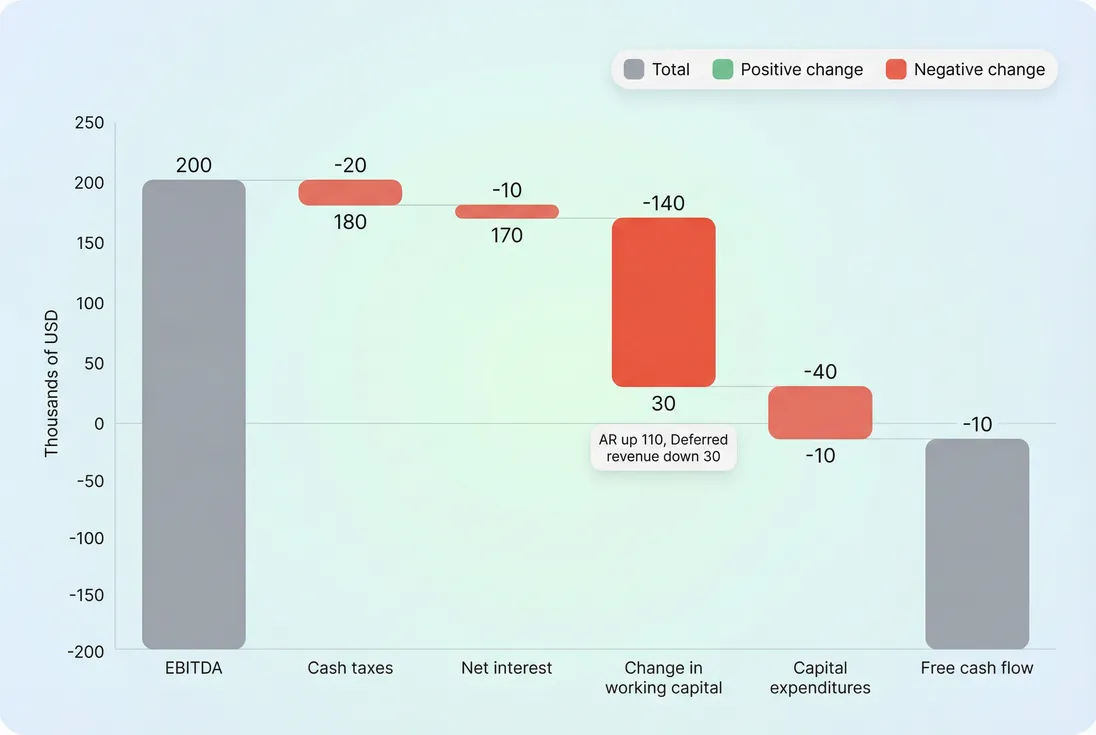

FCF is often "worse than EBITDA" in SaaS because working capital (like unpaid invoices) and capex pull real cash out of the business.

What FCF reveals (and hides)

FCF answers one question better than almost any other metric: is the business producing cash, or consuming it? That matters because cash is what determines runway, negotiating power, and whether you can invest through a downturn.

What FCF is great at revealing:

- Runway reality. It incorporates the timing of collections, refunds, and vendor payments.

- Capital efficiency. Strong businesses eventually convert revenue into cash at predictable rates.

- Financial stress early. A sudden drop in FCF often shows up before the P&L looks "bad."

What FCF can hide (if you don't look deeper):

- Billing timing effects. Annual prepay can inflate cash even if underlying unit economics are mediocre.

- One-time cash events. A tax payment, annual software invoice, or legal settlement can swing FCF.

- Accounting choices. Capitalizing software can improve reported profit while still reducing cash.

The Founder's perspective

I care less about whether we're "profitable on paper" and more about whether we can keep investing without raising on bad terms. FCF is the scoreboard for that. If FCF is consistently negative, every strategic plan needs a financing plan attached to it.

How to calculate FCF in SaaS

At its simplest, FCF is operating cash flow (CFO) minus capital expenditures (capex).

For many SaaS companies, capex is smaller than in manufacturing, but it's not zero. Typical capex includes:

- Computers and office equipment

- Capitalized software development (depends on your accounting policy)

- Data center or hardware (rare for modern SaaS, but possible)

Operating cash flow is where most SaaS nuance lives. A common "build" looks like this:

Working capital changes are often the difference between "great growth" and "cash crunch." In SaaS, the biggest drivers tend to be:

- Accounts receivable (AR): cash not collected yet (see Accounts Receivable (AR) Aging)

- Deferred revenue: cash collected upfront for service not yet delivered (see Deferred Revenue)

- Prepaids and payables: timing of annual tools, insurance, cloud commits, and vendor terms

Two useful companion metrics

FCF margin helps you compare across time and business size:

Burn is effectively negative FCF on a monthly basis (see Burn Rate and Burn in SaaS). In practice:

- If monthly FCF is -200k, you're burning 200k per month.

- If monthly FCF is +50k, you're self-funding 50k per month.

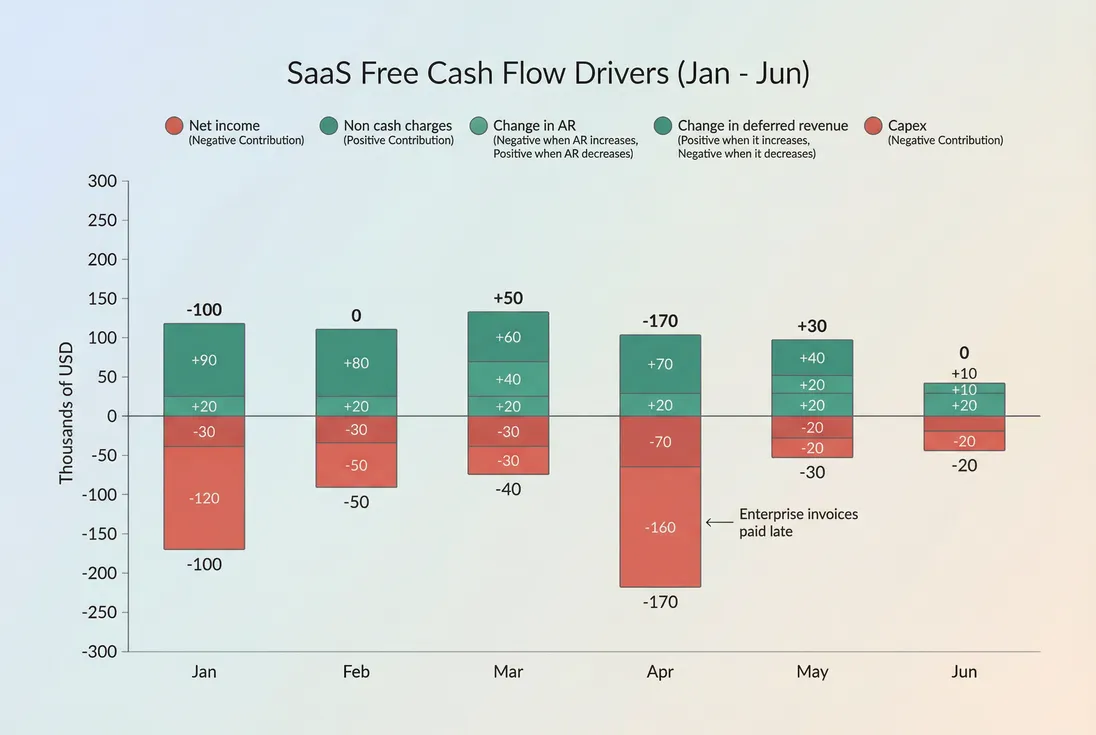

What moves FCF month to month

Most FCF surprises come from three buckets: operating performance, working capital, and capex. Founders who can quickly explain changes in each bucket make faster decisions—and tell a cleaner story to investors.

Operating performance: your core engine

This is the "boring" part: do gross margin and operating expenses leave you with cash-generating operations?

Key levers:

- Gross margin (see Gross Margin and COGS (Cost of Goods Sold))

- Headcount pace relative to growth

- Sales efficiency and payback (see CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost) and CAC Payback Period)

Practical interpretation:

- If ARR is growing but operating cash flow is getting worse, you're likely scaling costs ahead of monetization—or payback is drifting out.

Working capital: the SaaS cash trap

Working capital is why two SaaS companies with the same ARR and EBITDA can have very different cash outcomes.

AR up = cash down.

If you invoice annual contracts on net 60 and customers delay payment, you can "win deals" and still run out of cash. Track AR aging and tighten collections before you tighten hiring.

Deferred revenue up = cash up (temporarily).

If you push annual prepay, cash improves immediately—even if recognized revenue doesn't. This is not fake, but it is a timing effect. If renewals weaken later, today's cash boost can become next year's shortfall.

Refunds, chargebacks, and billing fees matter.

They hit cash quickly and can create noisy months:

Taxes and VAT can create "invisible" cash drains.

If you sell internationally, VAT handling can create cash obligations that don't resemble your revenue timing (see VAT handling for SaaS).

The Founder's perspective

When FCF swings, I don't ask finance for a bigger spreadsheet. I ask: did customers pay later, did we collect less upfront, or did we spend ahead of plan? Most "mystery" FCF issues are AR and deferred revenue, not some exotic accounting problem.

Capex: smaller, but not optional

SaaS capex is often lumpy:

- Laptop refreshes

- Office buildout (if any)

- Capitalized engineering work (policy-dependent)

If you capitalize software development, remember: it can make EBITDA look better while still reducing cash via payroll. That's one reason FCF is harder to "optimize cosmetically" than profit metrics.

Breaking FCF into drivers prevents overreacting: April looks like a spending crisis, but it's mostly late AR collections.

How founders use FCF to decide

FCF is most valuable when it changes what you do next week—not when it's a reporting artifact you review after the month ends.

Use FCF to manage runway and hiring

Runway is a simple relationship between cash and burn (see Runway):

- If average monthly FCF is -150k and you have 1.8M cash, runway is roughly 12 months.

- If FCF improves to -75k, runway doubles without raising.

The hiring implication is immediate: if you hire ahead of collections, you may improve product velocity while quietly cutting runway in half. This is where FCF beats "ARR is up" as a decision tool.

Use FCF to evaluate growth quality (burn multiple)

Founders often ask: "If we spend more, do we get efficient growth or just more burn?" Pair FCF with growth efficiency metrics like Burn Multiple and Capital Efficiency.

A practical approach:

- Track trailing 3-month averages of FCF and net new ARR.

- If burn multiple is rising while retention is flat, you likely have a go-to-market efficiency problem, not a temporary cash timing issue.

Related retention context:

Use FCF to pressure-test pricing and discounts

Discounting and annual prepay can "solve" FCF in the short run by pulling cash forward, but it can also:

- Reduce long-term expansion

- Train buyers to wait for end-of-quarter concessions

- Increase churn risk at renewal if value wasn't truly there

If you rely on discounts to fund operations, treat it as a strategy with costs (see Discounts in SaaS, plus ASP (Average Selling Price) and ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account)).

Use FCF to choose sales terms deliberately

Sales terms are a cash decision, not just a legal decision:

- Net 30 vs net 60 can be the difference between hiring and freezing.

- Large enterprise invoices create AR risk; AR risk creates FCF volatility.

If you're scaling enterprise, FCF discipline often means:

- Deposit or partial prepay for implementation

- Clear dunning and escalation

- Incentives for annual upfront payment when it makes sense operationally

When FCF "breaks" and how to fix it

FCF is straightforward, but founders commonly misinterpret it in predictable ways.

Mistake 1: treating FCF as the cash balance

FCF is a flow over a period; cash balance is a point in time. You need both:

- Cash balance answers: "How long can we survive?"

- FCF answers: "Is survival improving or worsening?"

Mistake 2: celebrating annual prepay as operational health

Annual prepay can be good (it reduces risk and improves cash), but it can also mask:

- Weak retention that will show up next renewal cycle

- Underpriced contracts

- Poor onboarding that delays value realization (see Time to Value (TTV))

Tie annual-prepay-driven FCF to retention reality using cohort views (see Cohort Analysis).

Mistake 3: ignoring revenue recognition vs cash timing

Revenue is recognized as you deliver service (see Recognized Revenue). Cash arrives when you collect. SaaS businesses often look "profitable" while starving for cash—or look cash-rich while losing money—because:

- Deferred revenue moves opposite to recognized revenue timing

- AR can grow without obvious P&L changes

Mistake 4: not isolating one-time cash events

A clean FCF review separates:

- Recurring operating cash generation

- Timing effects (AR and deferred revenue)

- One-offs (annual bills, taxes, settlements)

A simple monthly review format:

- FCF vs plan

- CFO vs plan

- AR aging movement (largest past-due accounts)

- Deferred revenue movement (annual prepay volume and renewals)

- Capex and any capitalization policy changes

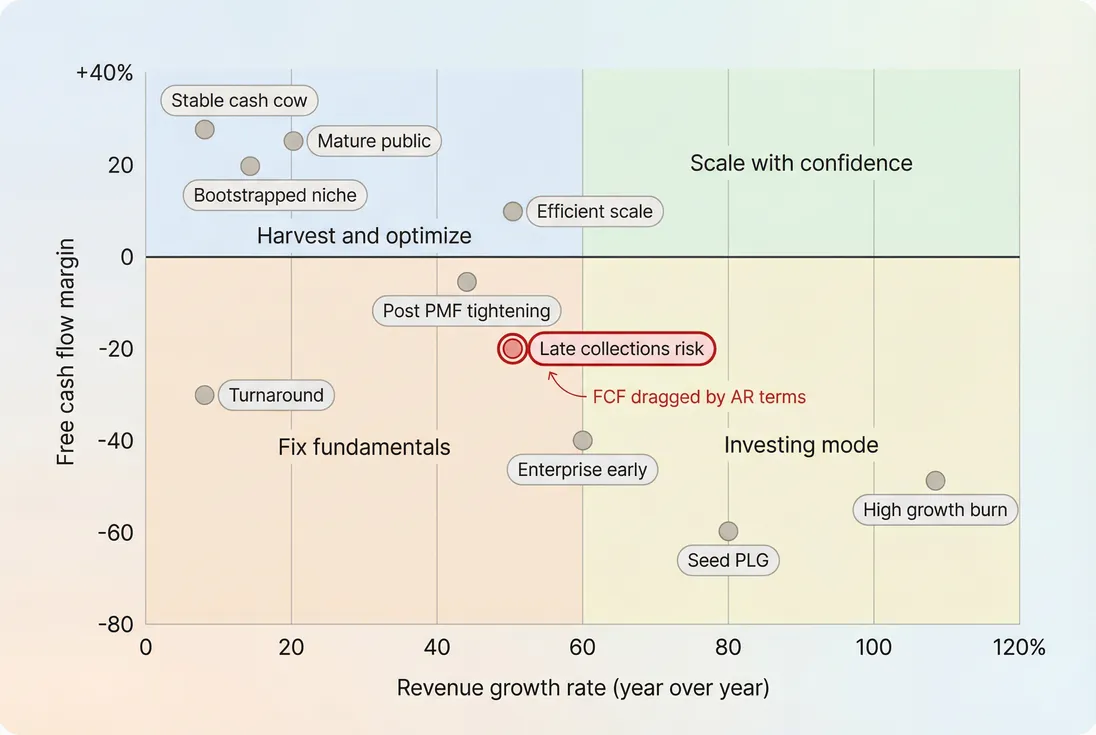

Benchmarks that are actually useful

"Good" FCF is stage-dependent, but founders still need guardrails. Use these as rough ranges, then adjust for your billing model (monthly vs annual), sales motion (SMB vs enterprise), and growth rate.

| SaaS stage (typical) | FCF margin (rough) | How to interpret |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-PMF | -100% to -30% | Cash is fuel for learning. Watch runway and make sure spend creates retention and activation improvements. |

| Post-PMF, scaling | -40% to -5% | Negative can be fine if payback is tight and retention is strong. Tighten AR and avoid "growth at any terms." |

| Efficient growth | -10% to +10% | You have levers: choose faster growth or faster breakeven. This is where planning discipline pays off. |

| Mature / durable | +10% to +30% | Strong conversion of revenue to cash. Focus on sustaining retention and avoiding working capital surprises. |

If you want one sanity check that investors and boards recognize, FCF margin is often paired with growth in frameworks like Rule of 40. Just remember: FCF is harder to "engineer" than EBITDA, which is why it carries weight.

FCF margin and growth together clarify strategy: high growth with deeply negative FCF demands great payback and retention—or a plan to change course.

A practical monthly FCF checklist

If you want FCF to drive decisions (not just reporting), review it the same way every month:

- FCF and FCF margin: directionally improving or deteriorating?

- Cash balance and runway: updated using the last 3 months of average FCF (see Runway)

- AR aging: what % is past due, and which customers dominate it (see Accounts Receivable (AR) Aging)

- Deferred revenue trend: are you funding operations with prepay, and is renewal health strong (see Deferred Revenue)

- Refunds and chargebacks: spikes that imply product or billing friction (see Refunds in SaaS and Chargebacks in SaaS)

- Efficiency context: burn multiple and payback alongside FCF (see Burn Multiple and CAC Payback Period)

The goal isn't to "maximize FCF" at all times. The goal is to make cash consequences visible so your growth plan, hiring plan, and sales terms are all consistent with how the business actually funds itself.

Frequently asked questions

Burn rate usually describes how fast your cash balance is shrinking per month. Free cash flow is the actual cash generated or consumed after operating expenses and capital expenditures. If FCF is negative, you are burning cash; if positive, you are self-funding. FCF also captures working capital swings like unpaid invoices.

It depends on stage and billing terms. Early stage SaaS often runs negative FCF while finding product market fit and scaling acquisition. Mid stage companies aim to narrow losses and show a credible path to breakeven. Mature SaaS often targets 10 to 30 percent FCF margin, with best in class businesses exceeding that in stable growth periods.

ARR can rise while cash falls if you are extending payment terms, building accounts receivable, paying large annual bills upfront, or expanding headcount faster than collections. Another common cause is switching from annual prepay to monthly billing, which reduces deferred revenue cash inflows. FCF reacts immediately; ARR reacts to contracted value.

Use FCF to decide how much growth you can safely afford. If you have strong retention and fast payback, negative FCF can be rational. If payback is long or churn is rising, negative FCF becomes fragile. A practical goal is to tie hiring and spend to clear leading indicators like retention and CAC payback.

Annual prepayments increase cash immediately and usually improve FCF in the short term, even though revenue is recognized over time. That can make the business look healthier than it is operationally. Founders should separate operational cash generation from timing effects by tracking deferred revenue changes and ensuring renewals and retention support that upfront cash.