Table of contents

Ebitda

Founders care about EBITDA because it's the fastest way outsiders will judge whether your SaaS business model can produce real operating profit at scale—not just growth. A quarter-to-quarter swing in EBITDA can change your ability to raise, your valuation multiple, and whether you can hire aggressively or need to slow down.

EBITDA means earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization. In plain English: it's an approximation of operating profit before (1) how you financed the company, (2) your tax situation, and (3) non-cash accounting charges tied to past investments.

What EBITDA reveals

EBITDA is not "cash in the bank." It's a signal about operating profitability and cost structure:

- Whether your core SaaS operations can generate profit before financing and accounting choices

- How much operating leverage you're getting as revenue scales

- Whether your expense base is structurally too high for your gross margin

- How "fundable" you look to lenders and some growth equity investors (many think in EBITDA multiples)

A useful way to interpret it is alongside EBITDA margin (EBITDA as a percent of revenue). It normalizes profitability across time and across companies.

The Founder's perspective: EBITDA is a forcing function. If your EBITDA margin is getting worse while revenue grows, you're not buying growth—you're leaking efficiency. That usually means you're scaling headcount, tools, or paid acquisition faster than your ability to retain and expand customers.

How to calculate it

There are two common ways to compute EBITDA. Pick one and be consistent.

From net income (common in reporting)

This version starts at the bottom of the income statement and adds back the "before" items.

From operating income (common in planning)

Operating income (EBIT) is already before interest and taxes. Then you add back depreciation and amortization:

A SaaS-friendly mental model

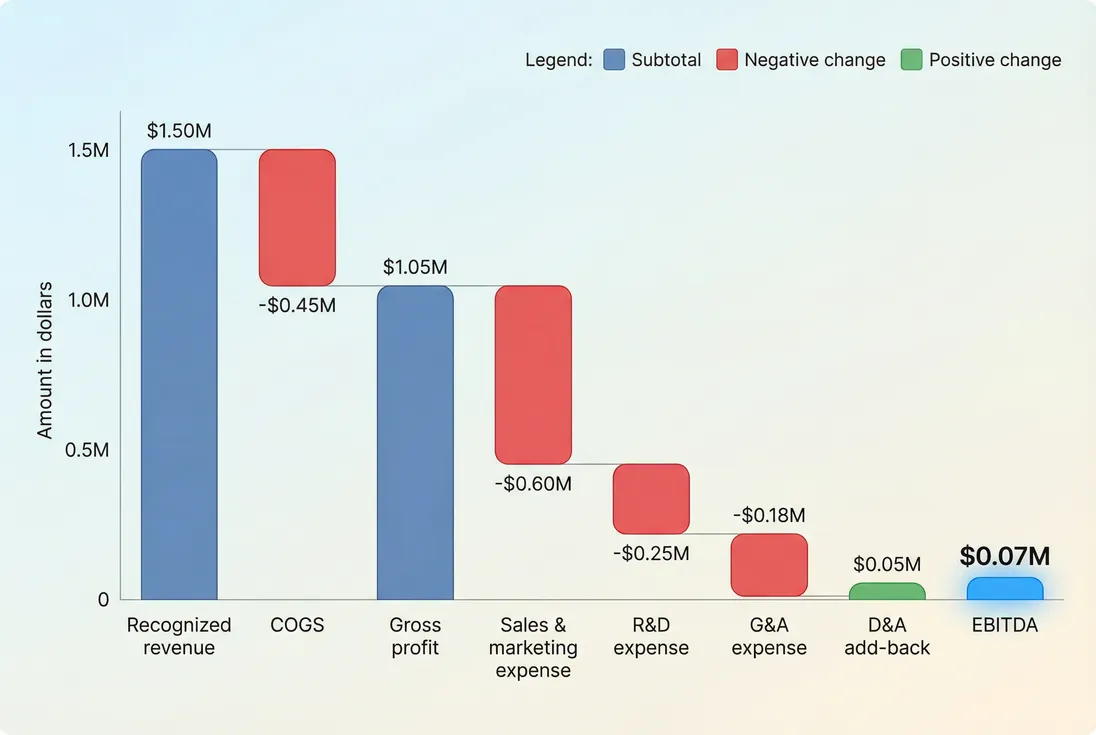

Most founders reason from revenue down:

- Recognized revenue (not bookings; see Recognized Revenue)

- minus COGS (hosting, support, third-party infra, etc.; see COGS (Cost of Goods Sold))

- equals gross profit (see Gross Margin)

- minus operating expenses (R&D, sales and marketing, G&A)

- plus D&A add-back

- equals EBITDA

A simple bridge from recognized revenue to EBITDA makes it obvious which cost blocks are driving the outcome and where leverage should come from.

EBITDA vs adjusted EBITDA

You'll often be asked for adjusted EBITDA, which removes items someone considers non-recurring or non-operational. There's no universal standard, which is exactly why it can become messy.

Common adjustments:

- One-time legal settlements

- Restructuring / severance

- M&A-related costs

- Sometimes stock-based compensation (controversial; some buyers add it back, others won't)

Rule: Always present a reconciliation from GAAP operating income or net income to adjusted EBITDA, with the rationale for each add-back.

What moves EBITDA in SaaS

EBITDA is a lagging rollup of many operating decisions. For SaaS founders, the most actionable drivers usually fall into five buckets.

1) Gross margin quality

Gross margin is your starting point for profit. Improving gross margin lifts EBITDA even if opex stays flat.

Typical SaaS gross margin drivers:

- Hosting and infrastructure efficiency

- Support cost per customer

- Third-party data/tooling fees inside COGS

- Professional services mix (services can dilute margin)

See Gross Margin and COGS (Cost of Goods Sold) for how teams commonly classify costs. Misclassification matters: moving costs between COGS and opex won't change EBITDA, but it will change gross margin and distort where you think the problem is.

2) Retention and expansion efficiency

Retention shows up in EBITDA indirectly but powerfully.

If your churn is high, you must spend more in sales and marketing just to stay in place, which pressures EBITDA. If expansion is strong, you can grow with less incremental spend.

Tie your EBITDA story to:

- GRR (Gross Revenue Retention)

- NRR (Net Revenue Retention)

- Net MRR Churn Rate (a practical month-to-month view)

- Expansion MRR and Contraction MRR

The Founder's perspective: When EBITDA dips, don't default to "cut costs." First ask: did we buy low-quality revenue (discount-heavy, wrong segment, poor onboarding) that raised churn and support load? Fixing retention often improves EBITDA without starving growth.

3) Sales and marketing scale economics

SaaS EBITDA often swings because sales and marketing is the largest discretionary lever.

What to watch:

- CAC rising due to channel saturation or weaker conversion

- Higher comp plans or SPIFFs to hit targets

- Longer sales cycles causing lower productivity (see Sales Cycle Length and Sales Rep Productivity)

EBITDA improves when revenue grows faster than S&M. But "cut S&M" can be a trap if it collapses pipeline. Pair EBITDA with:

- CAC Payback Period

- Sales Efficiency

- Burn Multiple (to connect growth spending to outcomes)

4) R&D and roadmap commitments

R&D is where SaaS teams accidentally lock in long-term EBITDA pressure. Hiring ahead of product-market fit, or building too many bespoke enterprise features, creates permanent cost.

Practical checks:

- Are you shipping changes that improve activation, retention, or expansion?

- Are you maintaining multiple product forks for a few large customers?

- Is technical debt increasing your support and infra cost? (See Technical Debt)

5) G&A creep

G&A is rarely the biggest line early, but it grows quietly through tools, contractors, finance, and people ops.

G&A is where "professionalization" can outpace scale. EBITDA margin often improves simply by setting clear approval thresholds, tool rationalization, and hiring plans tied to revenue milestones.

Interpreting changes without getting fooled

A higher EBITDA is usually good. But SaaS has several traps where EBITDA moves for reasons that don't improve the business.

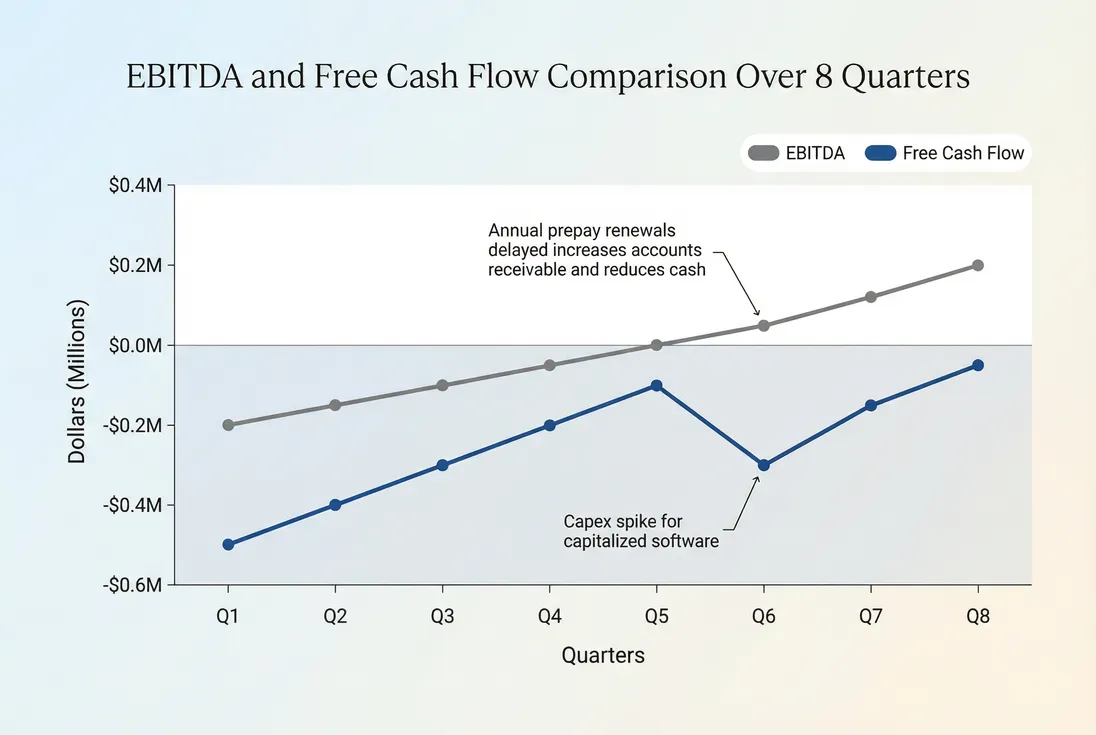

EBITDA is not cash flow

EBITDA excludes:

- Changes in working capital (cash timing)

- Capital expenditures (cash spent on long-lived assets)

- Interest and taxes (real cash costs)

That's why EBITDA can rise while cash decreases.

Use Free Cash Flow (FCF) and Burn Rate as the reality check.

EBITDA can improve while cash worsens due to working capital timing or capex. Treat EBITDA as operating signal, and cash flow as survival signal.

Two SaaS-specific reasons EBITDA and cash diverge:

- Accounts receivable and collections. If you invoice annual upfront but customers pay late, EBITDA may look fine while cash suffers. Watch Accounts Receivable (AR) Aging.

- Deferred revenue dynamics. Cash collected upfront increases cash immediately, while revenue is recognized over time. This can make cash look better than EBITDA in some periods and worse in others. See Deferred Revenue.

Depreciation and amortization are "non-cash," but not "not real"

EBITDA adds back D&A, but D&A exists because you previously spent cash (equipment, capitalized software, acquired intangibles). If you must keep investing to stay competitive, ignoring that spend will overstate economic profitability.

In SaaS, capitalization policies around software can materially change EBITDA:

- Expense software development → lower EBITDA today

- Capitalize and amortize → higher EBITDA today, amortization later

That's not inherently wrong; it just means compare companies carefully and understand the accounting policy.

Stock-based compensation and "adjustments"

Many SaaS companies highlight adjusted EBITDA that adds back stock-based comp. For founders, the practical view is:

- Stock is non-cash today, but it is a cost (dilution) (see Dilution in SaaS)

- If your plan assumes heavy SBC forever, "adjusted EBITDA positive" may still be economically weak

When someone shows adjusted EBITDA, ask:

- What exactly was added back?

- Does it recur every quarter?

- Would the business function without it?

How founders use EBITDA in real decisions

EBITDA is most useful when you treat it as a constraint and a tradeoff tool, not a trophy metric.

Set an EBITDA target that matches your strategy

A healthy target depends on your growth plan and access to capital.

A practical rule of thumb for planning (not a benchmark you should blindly copy):

| Company situation | Typical EBITDA posture | Why |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-PMF / early PMF | Negative | You're still proving retention and willingness to pay |

| Scaling with strong retention | Slightly negative to breakeven | Reinvesting while preserving option value |

| Late-stage / limited capital | Positive | You need self-funding and risk reduction |

| Mature / low growth | High positive | Optimization and cash generation matter most |

If you're using Rule of 40, EBITDA margin is often the profitability component that balances growth.

Decide when to hire (or pause hiring)

EBITDA helps answer: "If we hire this team, how much revenue must we add to stay on plan?"

A simple approach:

- Forecast revenue (ideally from pipeline + retention assumptions)

- Hold gross margin constant (or model modest improvements)

- Add headcount plan by function

- Track resulting EBITDA and runway (see Runway)

If a hiring plan pushes EBITDA down, ask whether it improves the drivers that later raise EBITDA: retention, expansion, sales productivity, or support efficiency.

The Founder's perspective: I like EBITDA as a guardrail for hiring sprees. If EBITDA margin drops because you hired ahead of proven demand, you're betting the company on forecasts. If it drops because CAC payback is excellent and retention is strong, you're buying a compounding asset.

Use EBITDA to sanity-check pricing and discounting

Pricing decisions hit EBITDA in two ways:

- Directly through revenue

- Indirectly through support load and customer quality

If you're leaning on discounts to close deals, you may be trading near-term growth for long-term EBITDA pressure. See Discounts in SaaS and connect it to ASP (Average Selling Price) or ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account).

A practical test: if discounting is rising, but churn and support tickets also rise, EBITDA will eventually pay the price.

Connect EBITDA to capital efficiency

Investors and boards often triangulate:

- EBITDA trend (operating profitability)

- Burn Rate (cash drain)

- Burn Multiple (growth per dollar burned)

- Capital Efficiency (how well you convert spend into durable ARR)

If EBITDA is improving but burn multiple is worsening, you might be cutting growth too hard. If burn multiple improves but EBITDA collapses, you might be overpaying for growth or letting costs sprawl.

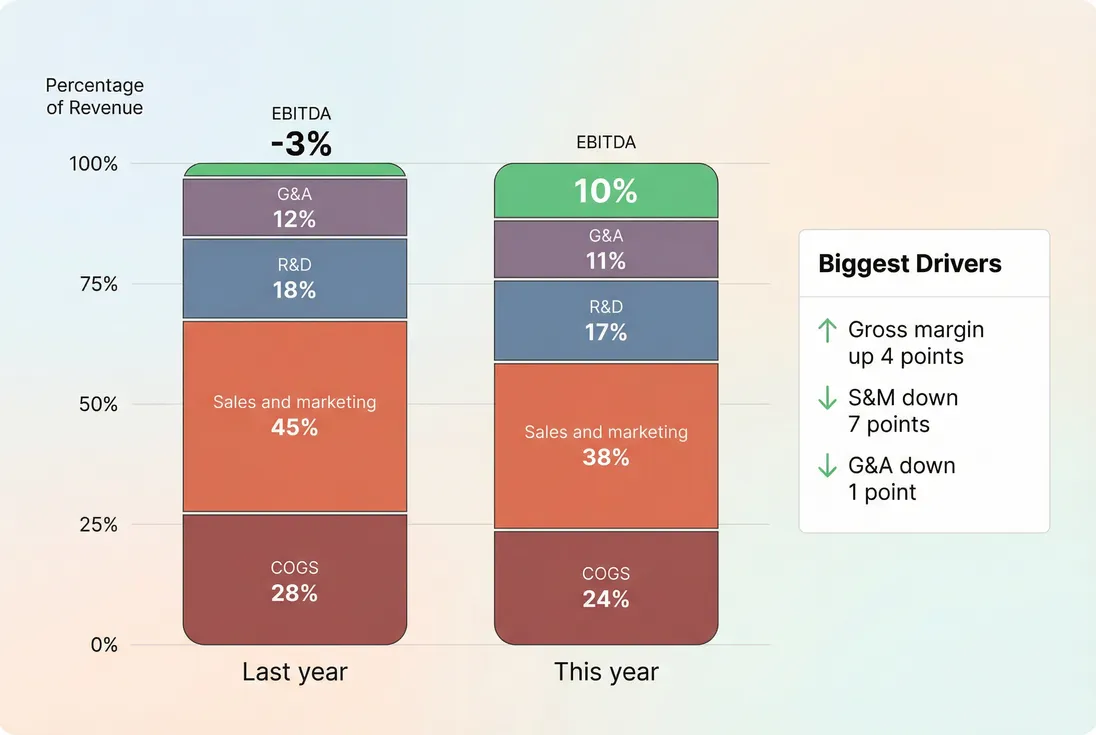

EBITDA margin changes are usually a mix of gross margin improvement and opex leverage. This view helps you pinpoint whether gains came from real efficiency or simple underinvestment.

When EBITDA "breaks" for SaaS

EBITDA becomes less decision-useful in a few common SaaS situations.

Heavy upfront investment periods

If you deliberately ramp sales capacity or invest in a major platform rewrite, EBITDA will look worse before results show up. In these cases, pair EBITDA with leading indicators:

- Pipeline quality and win rate (see Win Rate)

- Activation and time-to-value (see Time to Value (TTV))

- Early retention cohorts (see Cohort Analysis)

Services-heavy or implementation-heavy models

If onboarding and implementation are substantial, your COGS and revenue recognition can get complicated. EBITDA can still work, but you must:

- Be consistent about what sits in COGS vs opex

- Monitor gross margin and utilization (even if you don't formally track utilization as a metric)

Comparing across companies with different accounting

Two SaaS businesses can have similar economics but different EBITDA because of:

- Capitalization policy (software)

- Revenue recognition timing

- Acquisition amortization

- Expense classification (support in COGS vs opex)

When benchmarking, compare both EBITDA margin and the underlying structure (gross margin, S&M percent, R&D percent, G&A percent).

Practical cadence and reporting

For most SaaS founders, EBITDA is best used on a consistent rhythm:

- Monthly: internal operating review (but don't overreact to one month)

- Quarterly: board/investor narrative and planning updates

- LTM: trend signal (removes seasonality and one-off noise)

Common SaaS reporting set:

- EBITDA and EBITDA margin

- Gross margin

- Operating expenses by function

- Free cash flow and runway

- Revenue retention (GRR/NRR) and churn

- Sales efficiency and CAC payback

If you want one simple discipline: every EBITDA change should be explainable by a small number of drivers (pricing, margin, retention, S&M efficiency, headcount). If you can't explain it clearly, your chart of accounts or classification is probably hiding the story.

Summary: how to use EBITDA well

- EBITDA is a useful operating profitability proxy, not a cash metric.

- Track EBITDA margin to understand leverage as you scale.

- Interpret changes through gross margin, retention, and S&M efficiency—not just "cost cutting."

- Don't let adjusted EBITDA become a credibility problem; reconcile and justify add-backs.

- Always sanity-check EBITDA with Free Cash Flow (FCF), Burn Rate, and Burn Multiple.

Frequently asked questions

It depends on stage and growth rate. Early-stage SaaS often runs negative EBITDA while investing in acquisition and product. Mid-scale companies might target 0 to 15 percent. Mature, efficient SaaS can reach 20 to 35 percent. Interpret margin alongside growth, retention, and cash runway.

Use EBITDA to understand operating profitability before financing and non-cash charges, but manage the business to cash. SaaS can show decent EBITDA while burning cash due to working capital, capex, or deferred revenue dynamics. Pair EBITDA with Free Cash Flow and Burn Rate to avoid false confidence.

Investors want comparability across companies and periods, so they remove items they consider non-recurring or non-operational. Common adjustments include restructuring, litigation, and sometimes stock-based comp. The risk is overly aggressive add-backs. Always reconcile adjusted EBITDA to the income statement and explain each adjustment.

ARR growth and strong retention can improve EBITDA through operating leverage: fixed costs spread across more revenue and less spend is needed to replace churn. But growth can also depress EBITDA if acquisition costs rise faster than revenue. Tie EBITDA changes to NRR or GRR trends and CAC Payback Period.

Yes, mainly through classification and timing. Moving costs below the EBITDA line, capitalizing software instead of expensing, or adding back recurring "one-time" items can inflate EBITDA. The fix is consistency: define what sits in COGS and opex, track changes, and compare EBITDA to cash flow and headcount.